Fixed exchange rate regime

advertisement

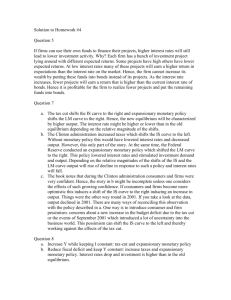

Department of Economics, University of Toronto Halina Kalita von dem Hagen ECO 208Y: MACROECONOMIC THEORY PROBLEM SET #4 – SOLUTIONS PART I: 1C 2C 3D 4A 5B 6B 7C 8A 9B 10A 11B 12B 13C 14C 15E 16B 17D 18A PART II: EVALUATE each of the following statements. Carefully explain your reasoning: 1. a. (first sentence) The optimal inflation rate equals to the negative of the real interest rate only if government spending may be financed through non-distortionary (lump-sum) taxes. Otherwise a welfare loss from having a non-optimal inflation rate has to be weighed against a welfare loss caused by having positive marginal tax rates. b. (second sentence) The statement is true for the closed economy. In the long run, inflation is determined by: inflation = rate of monetary growth - a*rate of growth of output + velocity changes. By controlling m, the monetary authority can control the inflation rate, setting it at an optimal level. The statement is also true for the open economy with flexible exchange rates. Under this regime, the authorities have a full control over MS, and hence over the inflation rate, and can therefore implement the "optimal" inflation rate as defined above. Under the fixed exchange rate the authorities use their foreign reserves to respond to pressures on the nominal exchange rate. Consequently, MS will not only be affected by the domestic credit component, but also by movements in foreign reserves. The authorities have therefore no control over MS and cannot choose the desired rate of inflation. Moreover, the relative version of the purchasing power parity implies that under the fixed exchange rate regime, the rate of domestic inflation will simply be equal to the rate of foreign inflation. The domestic economy must therefore accept the same inflation rate as prevails in the rest of the world. 2. a. Let’s assume an increase in the world real interest rate (you may also assume a decrease in which case the movements below will reverse their direction). NOTE: Instead of drawing a graph, I am describing it in what follows: Draw the initial equilibrium at A. See class notes for proper linkages between the IS-LM-BP and AS-AD graphs. As the world real interest rate rises and shifts up the BP curve, the new equilibrium on the ISLM-BP graph is determined by the intersection of the IS=BP (new) for the fixed exchange rate regime (label it FIX), and by the intersection of the LM=BP (new) for the flexible exchange rate regime (label it FLEX). It follows (if you did your graphs right!) that under the fixed exchange rate regime the AD shifts to the left (through the FIX point), whereas under the flexible exchange rate regime it shifts to the right (through the FLEX point). Read from the AS=AD (new) graph the new short-run equilibrium for each of the exchange rate regimes: it will be at F, above and to the right of A, for the flexbile exchange rate regime. It will be at X, below and to the left of A for the fixed exchange rate regime. In the long run, the short-run aggregate supply under the flexible exchange rate regime shifts to the left, and the equilibrium is at the intersection of the long-run AS with the new AD: FL point, vertically above point A. Under the fixed exchange-rate regime, the short-run aggregate supply shifts to the right, and the equilibrium is at the intersection of the long-run AS with the new AD pertinent to this exchange rate regime: XL point, vertically below point A. b. Short-run, flexible exchange rate regime, compare to the initial equilibrium at A: Output: increase (F point). Prices: increase (F point). Real interest rate: equals to the (new) world one, so: increase 1 Real wage rate: Y is higher, hence N is higher, hence MPL is lower, so real wages are lower Net exports: the IS curve through F is to the right of the one through A, and the shifts in the IS curve are due to both changes in nominal exchange rate and changes in domestic prices P, both of which affect only net exports NX. It follows that NX through F must be higher than through A Real money supply: no changes to nominal MS but P are higher, hence real money supply must be lower Short run, fixed exchange rate regime, compare to the initial equilibrium at A: Output: lower (X point). Prices: lower (X point). Real interest rate: equals to the (new) world one, so: increase Real wage rate: Y is lower, hence N is lower, hence MPL is higher, so real wages are higher Net exports: the IS curve through X is to the right of the one through A, and the only thing that shifted it is lower domestic prices which cause a depreciation in the real exchange rate, leading to higher net exports Real money supply: LM through X is to the left of the LM through A, and there were no exogenous shocks to money demand, this means: real money supply must be lower at X than at A. One can also argue: Y is lower, r is higher, hence L is lower due to these endogenous factors, so MS/P must be lower as well. c. Long run, flexible exchange rate regime, compare to the initial equilibrium at A Output: unchanged (FL point). Prices: increase (FL point). Real interest rate: equals to the (new) world one, so: increase Real wage rate: Y is unchanged, hence N is unchanged, hence MPL is unchanged, so real wages are unchanged Net exports: the IS curve through FL is to the right of the one through A, and the shifts in the IS curve are due to both changes in nominal exchange rate and changes in domestic prices P, both of which affect only net exports NX. It follows that NX through F must be higher than through A (however, they are lower than at F) Real money supply: no changes to nominal money supply but prices are higher, hence real money supply must be lower Long run, fixed exchange rate regime, compare to the initial equilibrium at A: Output: unchanged (XL point). Prices: lower (XL point). Real interest rate: equals to the (new) world one, so: increase Real wage rate: Y is unchanged, hence N is unchanged, hence MPL is unchanged, so real wages are unchanged Net exports: the IS curve through XL is to the right of the one through A, and the only thing that shifted it is lower domestic prices which cause a depreciation in the real exchange rate, leading to higher net exports (even higher than at X) Real money supply: LM through XL is to the left of the LM through A, and there were no exogenous shocks to money demand, this means: real money supply must be lower at X than at A. One can also argue: Y is unchanged, r is higher, hence L is lower due to the endogenous “r” factor, so MS/P must be lower as well. Note: since P are lower, this means that foreign reserves dropped more than P did, resulting in the overall contraction in MS/P. d. Flexible exchange rate regime An increase in the world interest rate leads to net capital outflows, i.e. excess supply of domestic currency in the foreign exchange market, resulting in a depreciation of the nominal E, hence a depreciation of real exchange rate, hence higher net exports. The IS curve shifts to the right, and the AD shifts to the right, both through FLEX. This leads to higher prices, leading to a lower real money supply (LM curve shifts to the left through F). Higher prices also lead to an appreciation of the real exchange rate, and lower net exports, shifting now the IS curve leftwards through F. 2 In the long run, prices increase even further, shifting both the LM and IS curves even more leftwards as explained above (through FL). The only lasting effect of the shock is higher prices, with output unchanged. However, the composition of output has changed: an increase in the real interest rate depressed investment but this was offset by higher net exports. Fixed exchange rate regime An increase in the world interest rate leads to net capital outflows, i.e. excess supply of domestic currency in the foreign exchange market. In order to support the nominal fixed E, the central bank must sell foreign reserves, hence nominal MS decreases, and with it – real money supply decreases, and the LM curve shifts to the left. With it, the AD curve shifts to the left, both through FIX. This leads to lower P, raising real money supply compared to the FIX point (LM curve shifts to the right through X). Lower prices also lead to a depreciation of the real exchange rate, and higher net exports, shifting now the IS curve rightward through X. In the long run, prices fall even further, shifting both the LM and IS curves even more rightwards as explained above (through XL). The only lasting effect of the shock is lower prices, with output unchanged. However, the composition of output has changed: an increase in the real interest rate depressed investment but this was offset by higher net exports. So: the statement is true for the short run (regardless of the exchange rate regime, output changes in the short run) but false in the long run (regardless of the exchange rate regime, output remains unchanged). 3. False. Once the country committed itself to the fixed-exchange rate policy (i.e. stable exchange rate), the country abandons its monetary freedom. Its money supply changes according to the situation in the balance of payments: MS = DC + R where DC = domestic credit component, R = foreign reserves. The country does not have therefore a control over its money supply as it cannot control R. Consequently, it loses control over its domestic price level. Relative purchasing power theory says: (change in E)/E = (change in foreign P)/foreign P - (change in P)/P Under the fixed exchange rate (changes in E) (=nominal exchange rate) are zero, and hence foreign and domestic inflation rate are equal. It follows that the stable exchange rate forces the country to accept the foreign inflation rate. On the other hand, if the country is committed to the domestic price stability, it follows from the above equation that it has to accept changes in E in response to changes in the rate of foreign inflation. Hence, no monetary policy by a single country can provide both a stable exchange rate and stable prices. 4. Always true under the flexible exchange rate system, maybe true (but not necessarily so) under the fixed exchange rate regime if the exchange rate was fixed at its equilibrium level (and hence no movements in reserves are necessary to support the exchange rate). For details (that you would need to include in your answer), see “Notes on the Open Economy”, Section on the Balance of Payments. PART III: 1. The Free Trade Agreement affects both the Mexican imports and exports. The IS curve shifts therefore, it is not clear, however, in what direction. If exports rise by more than imports do, the IS curve shifts to the right, if exports rise by less than imports do, the IS curve shifts to the left. Let's assume that it shifts to the left (if a student assumes a rightward shift, it is still OK, all the movements analyzed below will simply be in the opposite direction). Under a fixed exchange rate E, it is the IS and BP which determine the equilibrium level of AD (point B). Since the IS shifts to the left, so does the AD. The short-run equilibrium is determined by the intersection of the short-run aggregate supply (positively sloped) and the shifted AD: S 3 point. Domestic prices fall, and this shifts both the IS and the LM curves to the right from the B poin and through the S point. Short-run effects: Mexican output falls, and so does employment. The marginal product of labour (MPL) increases therefore, and so does the real wage rate (firms maximize profits, so MPL=W/P at all times). The ISS is to the left of the ISA, and the only components of aggregate spending which have autonomously changed are exports and imports. This implies that Net Exports (NX) at S are lower than NX at A. Similarly, because the LM curve at S is to the left of the LM curve at A, the real money supply (=the real money balances=M/P) must be lower at S than at A. And yet price level is lower at S than at A, which implies a lower nominal money supply (MS) at S compared to A. Since there were no shocks to the domestic credit component, MS drops only because foreign reserves decrease. In the long run, all contracts are re-negotiated; in view of lower prices, workers settle for lower nominal wages, and hence the SR aggregate supply shifts down through the L point. (The longrun equilibrium is determined by the intersection of the shifted AD curve and the long-run AS: L point.) Long-run effects: Ouput is unchanged, and so is employment, MPL and real wages. Net exports are the same as at A point (the ISL = ISA, and the only components of aggregate spending which were changing were net exports). The LM curve returns to its original position, and hence the real money balances at A and L must be the same. And yet prices are lower at L, implying a lower nominal money supply at L compared to A. This means that reserves must have decreased between A and L points. 2. SR: positively sloped AS curve. m up, AD shifts to the right. (a) Output expands, and so does employment. So: unemployment down. (b) real wages for sure decrease: N up, so MPL down, so W/P down. Nominal: it depends on the framework. In the NK case, they stay constant, in the NC case: they also increase but by less than prices do. (c) inflation rate increases in the short-run, overshooting argument. (d) Real exchange rate depreciates, and so does nominal. (e) Balance of trade improves (IS is to the right of the initial one). (f) Real interest rate is dictated by Rest-of-the World (perfect capital mobility). Long-run: (a) output and employment (unemployment) back to the original level. (b) real wages back to the original level, nominal wages increase matching a change in prices. (c) inflation rate matches an increase in m. (d) real exchange rate unchanged, nominal depreciates compared to the initial eqlm. (e) balance of trade returns to its initial level. (f) real interest rates unchanged 3. SR: SR AS positively sloped. Y* up, so our X up, IS shifts to the right, and so does AD. (a) output increases, unemployment decreases. (b) real exchange rate appreciates: P up (c) balance of trade improves (IS to the right of its original position). (d) R up (LM to the right of the original position despite the P increase) LR: (a) output & unemployment back to its original level (the truth is learnt). (b) real exchange rate appreciates even more (P up more). (c) balance of trade returns to its initial level (gains due to an increase in Y* are offset by an appreciation of the real exchange rate). (d) reserves up: P up and yet LM back at its original level. 4