superficial necrolytic dermatitis in a dog. a case report and review of

advertisement

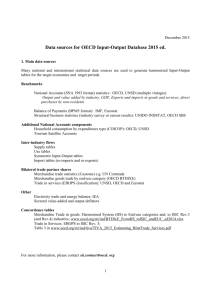

ISRAEL JOURNAL OF VETERINARY MEDICINE SUPERFICIAL NECROLYTIC DERMATITIS IN A DOG. A CASE REPORT AND REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE Waner T.1*, Anug A.M.2, and Aizenberg I.3 1. Veterinary Clinic, 9 Meginay Hagalil Street, Rehovot 76200, Israel. wanertnt@shani.net 2. PathoVet, 137 Shikun Banim, Kfar Bilu, 76965, Israel. 3. Koret School of Veterinary Medicine, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, P.O. Box 12, Rehovot 76100, Israel. *Corresponding author: Abstract: This report describes a case of superficial necrolytic dermatitis (SND) in an 11-year old Schipperke female spayed dog. The report includes the clinical presentation follow-up, clinical chemistry, histopathology and ultrasound findings. A diagnosis of SND was based on clinical presentation, clinical chemistry, ultrasound examination and supported by the histological findings of parakeratosis, acanthosis, basal cell hyperplasia and epidermal edema. The dog also developed renal failure two months after initial presentation, a finding that has not been reported previously. A review of the literature is presented including comparative aspects of the disease in cats, rhinocerus and humans. Introduction: Superficial necrolytic dermatitis (SND) is a rare and fatal disease of dogs characterized by typical skin lesions accompanied by hepatopathy, and uncommonly glucagonomas of the pancreas (1). The condition is also known as hepatocutaneous syndrome, metabolic epidermal necrosis and necrolytic migratory erythema. The pathogenesis appears to be related to an underlying metabolic hepatic dysfunction bringing about a cutaneous nutritional depravation, leading to necrotizing skin disease (2). This condition is unusual in being one of the relatively few skin conditions in which a diagnosis can be made from a skin biopsy (2). This report describes a case of SND in an 11-year old female spayed dog. The report includes the clinical presentation, clinical chemistry and ultrasound findings. A review of the literature is also presented. Case Report: An 11-year-old Schipperke female spayed dog was presented with a history of erosive skin lesions on the lateral abdomen and thorax, polyuria, polydypsia and weakness. It had a previous history of keratoconjunctivitis sicca that was treated with cyclosporin eye ointment (Optimmune Ophthalmic Ointment, Schering-Plough Animal Health, USA). Blood was collected for a complete blood count (CBC) and clinical chemistry. At this stage treatment was initiated and after one week with oral cephalexin monohydrate (Ceforal, Teva, Israel) at 250mg PO BID an improvement in the condition of the skin was noted. Clinical pathology findings at first presentation: The clinical pathology findings are presented in Table 1. The complete blood count (CBC) revealed a mild leukocytosis and neutrophilia without left shift. The neutrophils were mature and often hypersegmented. The platelet count was elevated. There was no apparent anemia in the smear, however marked polychromasia and nucleated RBC’s were noted (<2% basophilic rubricytes and metarubricytes). Serum clinical chemistry findings included an increased activity of the liver enzymes, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT). Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) activity was also increased. Serum cholesterol levels were decreased whereas triglycerides were increased. The serum albumin concentration was decreased. Urea concentrations were elevated although serum creatinine level was within the normal range. Electrolyte disturbances were detected: serum chloride and potassium levels were increased whereas sodium levels were decreased. Further investigations: A preliminary diagnosis of Cushing’s was suspected. A low dose dexamethazone test was carried out but proved negative. Three weeks later the condition deteriorated and the dog was presented with severe crusted fissured erosive lesions on the head and muzzle (with involvement of the mucocutaneous junction) (Figure 1). The footpads were hyperkeratotic and the nails deformed. A skin biopsy was taken from the muzzle area for histopathological assessment. Histological description: Biopsy of lesions from the facial area showed irregular epidermal hyperplasia with moderate parakeratosis and extensive serocellular crusting (Figure 2). Occasional areas of superficial epidermal edema (pallor) were evident (Figure 3). There was minimal basal cell hyperplasia and marked pigmentary incontinence. There was a mild superficial dermal infiltrate of lymphocytes and plasma cells. A diagnosis of superficial necrolytic dermatitis (SND) was made based on the histological findings of parakeratosis, acanthosis, epidermal pallor and mild basal cell hyperplasia. This diagnosis was supported by the chemistry findings, which were indicative of ongoing liver pathology. Ultrasound description and results: After two months the condition of the dog had deteriorated. At this stage abdominal ultrasound studies were carried out to evaluate the extent of the liver pathology and assess whether the pancreas was also involved in the pathogenesis of the condition. In addition blood was collected for a CBC and clinical chemistry panel. Ultrasound examination revealed pathological changes in the liver, spleen and iliac lymph nodes. The liver (Figures 4) was enlarged with the presence of multiple oval to round hypoechoic regions. The diameter of the hypoechoic areas reached up to 17 mm. In the spleen (Figure 5) a 20 mm hyperechoic area with a hypoechic center was detected. The iliac lymph nodes were mildly enlarged. No peritoneal or pleural fluids were detected and both kidneys appeared normal. No changes were detected in the pancreas. Clinical pathology findings after two months from the first presentation: The results of both the hematology and clinical chemistry findings are presented in Table 1. Deterioration in both hematological and biochemical parameters was evident. At this stage there was a moderate to severe anemia (microcytic hypochromic). Examination of the blood smear showed marked hypochromasia with the presence of rare ghost cells. The total white blood cell count had risen to 31,720 leukocytes/μL; a neutrophilia (28,500 neutrophils/μL) was the origin of the increased leukocyte count. The neutrophils were mature without left shift or toxicity, and the monocytes were predominantly bland. There was a marked increase (4-5 fold) in liver enzyme activities of ALP and ALT as compared to the first examination. In this examination aspartate aminotransferase (AST), which was not elevated in the first assay, was now increased 3-fold above the upper limit of the normal range. GGT and LDH activities remained increased at approximately the same level of the first examination. Serum creatinine was markedly increased along with the serum urea levels. A further indication of kidney pathology was the marked increase in serum phosphate levels. Chloride and potassium levels returned to within the normal range while the sodium level remained decreased. The triglyceride concentration was markedly decreased. Serum albumin levels remained low. The dog was euthanized on the request of the owners who refused a postmortem examination. Table 1: Hematology results at first presentation and at two months later Differential leukocyte count Table 2: Biochemistry at first presentation and two months later Figure 1: Dermal lesions three weeks after initial complaint: Severe crusted fissured erosive lesions on the head, muzzle with involvement of the mucocutaneous junction e 2: Biopsy of lesion from the facial area ng irregular epidermal hyperplasia with ate hyperkeratotic parakeratosis (small d arrow) and extensive serocellular crusting. is minimal basal cell hyperplasia and d pigmentary incontinence (arrow heads). of superficial epidermal edema (pallor) are t (large headed arrows) Figure 3: Biopsy of a lesion from the facial area showing details of superficial epidermal pallor (arrows). There is a mild superficial dermal infiltrate of lymphocytes and plasma cells. Note the pigmentary incontinence (arrow heads). Liver ultrasound: Note the presence of Figure 5: Spleen ultrasound: Note the 20 mm val to round hypoechoic regions (arrows). hyperechoic area with a hypoechic center eter of the hypoechoic areas reached up to Discussion and review of the literature: Superficial necrolytic dermatitis (necrolytic migratory erythema or hepatocutaneous syndrome) is an uncommon skin disorder associated with an underlying systemic disease. The condition was first described in a human patient with a pancreatic neoplasm in 1942 (3). In humans SND is seen most commonly in patients with a glucagon-secreting pancreatic α-cell neoplasm (4). In contrast, in dogs the majority of cases occur in association with hepatopathy, and less commonly with a glucagon-secreting tumor (5). The first canine case of SND,then termed canine diabetic dermatosis was described in 1986 (6). The name canine diabetic dermatosis was used due to the tendency of dogs for glucose intolerance and in some cases for the development of diabetes mellitus. The pathogenesis is probably related to nutritional deficiencies or metabolic abnormalities caused by liver dysfunction. Nutritional deficiencies that may be associated with this condition include zinc deficiency, hypoaminoacidemia or decreased essential fatty acids. Profound hypoaminoacidemia has been found to be a consistent feature of the disease with up to 80% reduction in a number of amino acids (7). It has been hypothesized that the contributing defect is a metabolic hepatopathy that increases hepatic metabolism of amino acids (8). Canine SND is primarily a disease of older dogs with a mean age of about 10 years. The typical age of onset of SND corresponds to the age range of the dog described in this report, which was 11 years of age. There are indications that there may be a higher incidence in small breeds (as in our case), and that male dogs (the present case was a female) may be overrepresented (2). In relation to this report, two cases in Schipperke breed have been previously reported (1). Common presenting complaints other than dermatological lesions include lethargy or anorexia, weight loss and difficulty or pain on walking. In the case reported here the main presenting signs were weakness, polyuria and polydypsia. Clinical pathology revealed a high urea level probably due to mild dehydration. The cause of the polyuria and polydypsia is not clear but may be due to the ongoing liver pathology (9). The commonly reported sites of cutaneous lesions in the dog rank from footpads, feet (haired skin), facial mucocutaneous junctions, distal limbs, perineal and perianal area, nose and muzzle, elbows, ventral abdomen, perivulva, pinna and oral cavity. In the case presented here, at first presentation, lesions were present on the distal limbs and lateral abdomen. Three weeks later the typical presentation of cutaneous lesions of the mucocutaneous junctions of the face and muzzle were seen, with lesions of the footpads and nails. The presentation of lesions on the mucocutaneous junction of the face is reported in about 61% of cases (1). Blood chemistry results were similar to the commonly reported clinical laboratory findings for dogs with SND. Increased activity of serum ALP and AST is very commonly reported, as in this report. Anemia and leukocytosis have been reported to occur in about 43% of cases, and were also present in this case albeit not on first presentation but two months later. At this stage therewas a moderate to severe microcytic hypochromic anemia. Hypoalbuminemia is reported to occur in only 29% of cases and was present in this case. Diabetes mellitus and hyperglycemia, which is present in about 40% of cases, was not evident in this instance. Interestingly this dog also developed subacute to acute renal failure two months after initial presentation with markedly increased serum urea, creatinine and phosphate levels. Renal failure is not usually associated with this SDN. The changes in the electrolyte levels of sodium, potassium and chloride are not fully understood but are probably related to the ongoing liver pathology and the developing kidney failure. Plasma glucagon concentrations were not carried out. The reliability of this assay in dogs is considered by some to be to be questionable as elevations have also been seen in cases that do not have pancreatic tumors (10). As no definite conclusions can be drawn in this case regarding the presence or absence of pancreatic neoplasia, it has been suggested that the condition be described as SND-ND (SND-not conclusively determined) as apposed to SND-GS (glucagonoma syndrome) or SND-HS (hepatocutaneous syndrome) (1). Ultrasonographic results in this study corresponded to those seen in previous studies of dogs with SND (11), where a “Swisscheese appearance” of the liver was evident. The nature of the ultrasound changes seen in the spleen and iliac lymph nodes in this case is unclear due to the lack of further pathological investigations. The typical light microscopic finding is the classic “red, white and blue” appearance with is pathognomonic for SDN. These pathognomonic lesions may be focal. “Red” represents diffuse parakeratosis with crusting, ”white” corresponds to epidermal pallor due to both hydropic swelling of keratinocytes and spongiosis., and “blue” represents basal cell hyperplasia. Perivascular superficial cellular infiltrates may be present in the dermis consisting of neutrophils, macrophages, lymphocytes and plasma cells (12). The clinical differential diagnosis should include pemphigus foliaceus, zinc responsive dermatosis and generic dog food dermatosis. Pemphigus foliaceus is a pustular dermatitis with involvement of the dorsal muzzle, planum nasale, pinnae, periorbital skin, and footpads. Acantholytic cells are a prominent histological feature(2). Zinc responsive dermatosis is predominantly seen in Siberian huskies and Alaskan malamutes and is characterized by crusting, scaling and alopecia around the eyes, mouth chin and ears (2). Generic dog food dermatosis is an uncommon to rare syndrome seen due to the feeding of poor quality food. The condition is seem most often in younger dogs and the lesions are usually seen on the muzzle, mucocutaneous junctions, pressure points, flexure surface and distal extremities(2). In humans the condition is a cutaneous marker for pancreatic islet cell tumor and is less commonly associated with hepatic cirrhosis. Besides, the condition may be associated with chronic pancreatitis, Crohn’s disease, celiac sprue, and malabsorption syndrome (1). There have been only a few reports of SND in the cat that have been associated with a number of diverse conditions including pancreatic carcinoma, thyroid amyloidosis and hepatopathy and intestinal lymphoma (2). A high incidence of SND has been reported in the black captive rhinoceros (Diceros bicornis). The remarkable aspects of the disease in these animals include an incidence of about 50% in the captive population, the mortality rate is only 57% (compared with dogs which is estimated as high as 87%) and that only 23% of the cases in rhinos are associated with liver disease without any cases of pancreatic neoplasia (1). In conclusion, this article presents a case of SND in an 11-year old Schipperke female dog which was fairly typical for the disease. Distinguishing features included symptoms of polyuria/ polydyspia and the development of an atypical renal failure in a relatively short period of time. Renal failure associated with SND has not been reported previously. This case represents a diagnostic challenge in which clinical, clinical-pathological and histopathological findings are combined with ultrasound results for the diagnosis of this poorly understood metabolic disorder. References: 1. Byrne, K.P.: Metabolic epidermal necrosis-hepatocutaneous syndrome. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 29:1337-1355, 1999. 2. Gross, T.L., Ihrke, P.J., Walder, E.J. and Affolter, V.K., Necrotizing diseases of the epidermis, in Skin Diseases of the Dog and Cat. 2005, Blackwell Science: Oxford,England. p. 75-98. 3. Becker, S.W., Kahn, D. and Rothman, S.: Cutaneous manifestations of internal malignant tumors. Arch Dermatol Syphilol. 45:1069-1080, 1942. 4. Marinkovich, M.P., Botella, R. and Datloff, J.: Necrolytic migratory erythema without glucogonema in patients with liver disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 32:604609, 1995. 5. Turek, M.M.: Cutaneous paraneoplastic syndromes in dogs and cats: A review of the literature. Vet Dermatol. 14:279- 296, 2003. 6. Walton, D.K., Center, S.A. and Scott, D.W.: Ulcerative dermatotis associated with diabetes mellitus in the dog. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 22:79-88, 1985. 7. Gross, T.L., Song, M.D., Havel, P.J. and Ihrke, P.J.:Superficial necrolytic dermatitis (necrolytic migratory erythema) in dogs. Vet Pathol. 30:75-81, 1993. 8. Outerbridge, C.A., Marks, S.L. and Rogers, Q.R.: Plasma amino acid concentrations in 36 dogs with histologically confirmed superficial necrolytic dermatitis. Vet Dermatol. 13:177-186, 2002. 9. Taylor, S.M., Polyuria and polydypsia, in Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine, S.J. Ettinger and E.C. Feldman, Editors. 2000, W.B. Saunders Co.: Philadelphia. p. 85-92. 10. Miller, W.H.J., Scott, D.W. and Buerger, R.G.: Necrolytic migratory erythema in dogs: A hepatocutaneous syndrome. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 26:573-581, 1990. 11. Jacobson, L.S., Kirberger, R.M. and Nesbit, J.W.: Hepatic ultrasonography and pathological findings in dogs with hepatocutaneous syndrome: new concepts. J Vet Intern Med. 9:399-404, 1995. 12. Yager, J.A. and Wilcock, B.P., Color atlas and text of surgical pathology of the dog and cat. 1994: Mosby.