Intermediate Methods in Epidemiology 2008 Exercise No. 2

advertisement

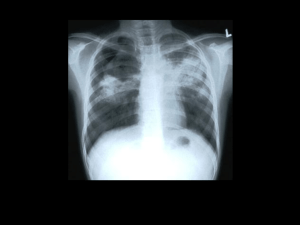

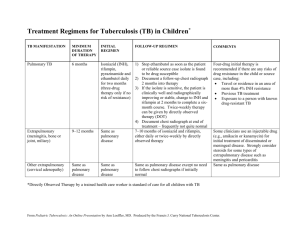

Intermediate Methods in Epidemiology 2008 Exercise No. 2 - Measures of Disease Frequency and Association Main topics covered in this laboratory exercise: I. The relationship of incidence rates and ratios to prevalence rates and ratios and how these relate to the interpretation of cross-sectional studies. II. Calculation of a. Relative Risk and Relative Odds: Similarities and differences b. Relative odds in matched and non-matched samples c. Confidence limits for relative odds and relative risks III. Case-Control Studies a. Assumptions b. Controls 1. Non-cases 2. Population sample IV. Random variability vs. bias V. Matched studies a. Advantages and disadvantages b. Assumptions VI. When and how to use a statistical significance trend test. Department of Epidemiology - Johns Hopkins University - Copyright 1999 This laboratory exercise assumes familiarity with the following concepts: Incidence and prevalence Case fatality rate Relative risk and relative odds Cohort and case-control study design Matched case-control design Confounding Matching as a method of confounder control Sampling variability How to label graphs 2 PART I: MEASURES OF DISEASE FREQUENCY 1. BACKGROUND INFORMATION The material for this part of the exercise will all be taken from a long-term study of tuberculosis in Muscogee County, Georgia. In 1946, the county had a population of about 100,000 consisting of a city of 75,000 population and surrounding suburban and rural areas. The city is industrial in character and is adjacent to a large military post. Thirty per cent of the population was black. Survey and Follow-up Procedures In May and June, 1946, a combined tuberculosis-venereal disease survey aimed primarily at persons over 15 years of age was conducted by the local and state health departments with federal aid. Three months later a special census of the county population was made which permitted a better estimation of the completeness of coverage than the Federal Census figures because individuals enumerated in the special census could be matched against those reached in the survey, and because the 1940 Federal Census was rather badly out of date. A 70 mm photofluorograph1 was offered to each participant over the age of 12 years. Each photofluorograph was interpreted independently by two readers and all suspects of either reader were requested to return for a standard 14 x 17 inch chest radiograph. Persons classified as tuberculosis cases or suspects after the 14 x 17 inch X-ray were advised to remain under observation for at least five years. During this period examinations were to be repeated at least every three months. Only a few persons with clear-cut evidence that the suspected abnormality was not tuberculous were discharged from follow-up before the end of the five year period. Tuberculin tests were done on most cases and suspects, and skin tests with fungal antigens were done where indicated. Sputum examinations, including cultures, were done on about one-half of the cases and suspects, including nearly all who were producing sputum or were suspected of having active disease. Gastric washings were not obtained. 1 A photofluorograph (PF) is a photograph of an image on a fluorescent screen produced by X-rays. Photofluorography of the chest is highly automated and rapid, and when used on a mass scale, is usually inexpensive. A chest photofluorogram has been shown to reveal chest abnormalities as accurately as a full-sized chest radiograph (Birkelo et al., JAMA, 133:359, 1947). Usually however, an abnormality detected by photofluorography is checked by a full-sized chest radiograph. 3 On the average, each patient had more than 12 clinic visits, with radiographs, up to July 1, 1952. Sixty per cent of the persons initially classified as having tuberculous were examined in the 5th year after the survey; 11 per cent had died; 8 per cent had moved away; and 21 per cent were not examined in that year. Almost all of the last group were known to be living and apparently well. Case-finding Subsequent to the Survey In 1950, 75,000 persons were radiographed in a second mass survey of the metropolitan area exclusive of the military post. In addition, approximately 22,000 screening films were made each year as a result of the pre-employment and food-handler requirements, prenatal services, referral by private physicians, or other resources. Death certificates, hospital records and other sources of medical information were continuously scanned for information on known cases and suspects, as well as for possible unreported or unrecognized cases. Reporting is quite complete in this community, and it can be assumed that all diagnosed tuberculosis came to the attention of the health department, except for persons who had moved away prior to their diagnosis. During the five-year period following the 1946 survey, new cases of tuberculosis were matched to the file of 1946 survey participants. Observations on these cases were continued to June 1952 to give even the most recently diagnosed case a follow-up period of at least one year. Tuberculosis deaths among the cases diagnosed in the 1946 survey were also counted to June 1952. Migration from the Community To estimate the number of persons remaining in the area in 1952, a sample, systematically selected, was visited in 1961 as part of a study of blood pressure levels. The proportion of persons who had left the county is shown in Table 1. The very few individuals whose whereabouts could not be ascertained were counted as having moved. ( 1) From the data in table 1, briefly describe the differences between individuals who emigrate and those who do not in this population. What kind of implications could these differences have for epidemiologic studies based on this population? In addition, the residence status of a systematic sample of participants in the 1950 survey who were then over 20 years of age was investigated in 1964. Sixty-six percent were found to be still residing in the study area, with no differences between those who reacted to tuberculin in 1950 and those who did not. (A reactor in this instance was defined as a person having five or more mm of induration to 5 TU of tuberculin.) 4 Table 1 Emigration between Sept. 1, 1946 and July 1, 1961 in a sample of the surveyed population, by race, sex, age and subcutaneous fatness in 1946, Muscogee County, Georgia. Number in sample Per cent emigrated 464 30 95 35 183 36 67 24 119 27 15-34 262 39 35-54 168 23 55+ 34 15 0-4 mm. 157 35 5-9 mm. 216 32 10+ mm. 91 22 Characteristics Total Race-Sex White Males White Females Black Males Black Females Age in 1946 Fat thickness in mm. over trapezius muscle* * Percentages adjusted to race-sex-age composition of total examined population. 5 PREVALENCE vs. INCIDENCE Strictly speaking the term relative risk is defined as the ratio of two incidence risks. However, this term is commonly used with many quantities which approximate this ratio such as the ratio of two rates, odds, or prevalences. This laboratory exercise uses the term "relative risk" in this looser sense, however it is important to note how each estimate of the relative risk is calculated. More specific uses of these and related terms are described in the relevant lecture. Prevalence of Tuberculosis Table 2 presents the number of persons screened, by race and age, and the cases of pulmonary tuberculosis determined at the end of the 5-year observation period to have had tuberculosis when surveyed. The tuberculosis deaths among these cases to June 1952 is also given. Table 2 Prevalence of pulmonary tuberculosis in 1946 survey, by race and age, Muscogee County, Georgia. White Black Total <45 45+ <45 45+ Population screened in survey 38,190 17,699 4,939 12,336 3,216 Cases of tuberculosis 568 134 245 119 70 Prevalence/1000 14.9 7.6 49.6 21.8 6.53 2.87 Prevalence Ratio 1.0 Tuberculosis deaths to June 1952 34 2 Case fatality, % 6.0 1.49 Incidence of New Cases 6 5 2.04 16 11 15.71 In similar fashion, the number of new cases known to have developed among the screened population during the next five years, together with the tuberculosis deaths among them and the mid-point populations at risk are shown in Table 3. Table 3 Incidence of new cases of pulmonary tuberculosis per 1000 estimated survey-negative population during a 5-year period, 1946-1951, Muscogee County, Georgia. White Black Total <45 45+ <45 45+ 33,656 15,554 4,348 10,915 2,839 New Cases of tuberculosis 110 22 66 10 Incidence/1000/year 0.65 .28 Estimated midpoint population 12 .70 .55 Relative Risk 1.0 Tuberculosis deaths to June 1952 Case fatality, % 31 28.2 1.96 3 1 13.6 8.3 2.50 22 5 50.0 ( 2) Calculate the prevalence, incidence and case fatality for younger blacks in Tables 2 and 3. Note that for Table 3, the new cases of tuberculosis were accumulated over a five year period so that the calculation of the annual incidence rate must account for this. Do you observe the same patterns of associations of race and age with tuberculosis prevalence and case fatality from Table 2 (cross-sectional data) as you do with tuberculosis incidence and case fatality from Table 3 (prospective data)? 7 A high degree of tuberculin sensitivity is also considered to be a risk factor for tuberculosis in many populations. Data on this characteristic from Muscogee County, Georgia can also be used to compare results of a cross-sectional and a prospective study. As mentioned earlier, a community-wide screening project was carried out in 1950. In this project, participants were given a standard tuberculin skin test and a chest photofluorograph. Persons with abnormal photofluorographs were recalled for a 14x17 radiograph and a clinical examination. Table 4 shows the frequency of pulmonary tuberculosis among the screened population by size of tuberculin reaction (diameter of induration in mm). Table 5 shows the rate of new tuberculosis developing during the next 14 years among the population with normal chest radiographs in 1950, according to the size of their tuberculin reaction in 1950. Table 4 Cases of pulmonary tuberculosis detected in surveyed population by size of tuberculin reaction, Muscogee County, Georgia, 1950. Induration (mm) No. of Cases Cases per 1000 496 11.8 0- 2 34 4.1 3- 4 38 4.5 1.1 5- 7 71 8.5 2.1 8-12 142 16.9 13+ 211 25.2 Total 8 Relative Risk 1.0 6.1 Table 5 Cases of pulmonary tuberculosis among surveyed population developed during a 14-year period (1950-1964), by size of tuberculin reaction in 1950, Muscogee County, Georgia. Induration (mm) No. of Cases Cases per 1000 Relative Risk Total 239 26.6 0 20 8.7 1.0 1- 4 43 16.8 1.9 5- 9 66 26.9 3.1 10 - 14 72 61.9 15+ 38 77.0 8.9 ( 3) Complete tables 4 and 5, i.e., calculate the missing relative risks, using persons with the smallest tuberculin reactions as the reference group. Note that relative risk is calculated as rate of exposed divided by rate of unexposed (e.g., 0 mm or 0-2 mm induration). Is the association of tuberculosis with size of reaction similar in the cross-sectional and prospective studies? 9 [To assist you with answering the above question, it would be wise to plot the relative risk values from the two tables onto a single piece of semi-log graph paper. (x-axis = mm induration, and y-axis = relative risk). Label the graph succinctly but completely.] ( 4) When are associations observed from cross-sectional (prevalence) studies similar to those observed from prospective studies? 10 PART II: RELATIVE RISK AND RELATIVE ODDS For this part of the exercise, a defined population has been selected among persons identified in a private census of Washington County, Maryland, as of 15 July 1963, namely white males and females who were aged 45 through 64 inclusive on the census date. This subset includes over 95% of the white population in the county in that age range. Ethnic groups other than whites have been excluded because there is some evidence that their experience with the illness of interest (cancer of the colon) is different from that of whites, and there are too few nonwhites in Washington County to allow reliable estimates of their experience. A further simplifying assumption is that there were no losses (e.g., migration) from the population. White males and females aged 45 through 64 on 15 July 1963 who could be identified in the 1963 census lists were the source population for this study. Cases were in the county cancer register as having had a diagnosis of cancer of the colon first made in the 12-year period 15 July 1963 through 14 July 1975. It is believed that identification of cancer cases is very nearly complete, but this cannot be known for certain. For the purposes of this exercise, assume that ascertainment was complete. ( 5) Under what circumstances would incomplete ascertainment affect estimates of relative risks or relative odds? Cancer of the colon has been reported to be more common in urban populations than in rural populations, and more common in high socio-economic groups (as measured by average education levels in the area in which they reside) than in lower socio-economic groups. Table 6 shows the information needed to estimate the relative risks of developing colon cancer by urban residence and high socio-economic status (defined as having completed 13 or more grades of school). Urban includes Hagerstown suburbs. 11 Table 6 Number and rate per 1000 white residents of Washington County, MD aged 45 through 64 years on 15 July 1963, of cases of cancer of the colon diagnosed 15 July 1963 through 14 July 1975, by residence and grades of school completed. Cases Initial characteristic Population Total 18,125 116 Urban 9,351 50 Rural 8,774 66 2,418 23 15,707 93 N Rate (per1000) Relative risk 95% Confidence limits** Relative odds 0.71 0.49 - 1.03 0.71 6.4 Residence 5.3 7.5 1.00 1.00 5.9 1.00 1.00 Grades completed 13+ <13, NS* * NS: not stated. ** 95% confidence limits for the Relative Risk, see formula below. See lecture handout entitled "Measures of Association" for method of calculating the confidence limits for the relative risk (Katz et al, Biometrics 34: 469-74, 1978). Briefly, the variance of the natural log of the relative risk can be approximated as follows (Katz et al. 1978, Kahn & Sempos, pp. 62-63):2 b d VAR (ln(RR)) = a + c a+b c +d 2 When giving formulas for variance estimates of measures of association for unmatched data in a 2x2 table, the following notation is used in this exercise: Cases Controls a b c d 12 ( 6) Complete the blanks in table 6. Do the relative risks and odds ratios differ from each other to any meaningful degree? Be sure you know under what conditions they would be expected to be similar and markedly dissimilar. A sample of controls was selected for the source population who were never identified as cases. Pertinent information was abstracted from the listing and entered on the computer file in the same way that had already been done for the 116 cases. Table 7 shows the results. Table 7 Residence and grades of school completed for cases of cancer of the colon and a sample of controls, white males and females aged 45 through 64, identified in the 1963 census of Washington County, MD Initial characteristic Cases Controls 116 116 Urban 50 66 Rural 66 50 23 12 Total Relative odds 95% Confidence limits Residence 1.00 Grades completed 13+ <13, NS* 93 * NS: Not stated ( 7) What type of epidemiologic study is this? 13 104 2.14 1.00 1.01 - 4.55 See lecture handout entitled "Measures of Association" for method of calculating these confidence limits (Woolf B: Ann Hum Gen 10:251-253, 1955). Briefly, the variance of the natural log of the odds ratio can be approximated as follows (Woolf, 1955, Kahn & Sempos, pp. 56-58): VAR (ln(RO)) = 1 1 1 1 + + + a b c d where a,b,c, and d are the entries in the 2x2 table (see footnote on page 12). ( 8) What is the total reference population from which the control group was selected? ( 9) Calculate the relative odds and its 95% confidence limits for residence in table 7. (10) Do the results in this table differ from those in Table 6? Why? In this exercise, you have the unique opportunity of seeing how closely the control odds (urban/rural; 13+/0-12, NS) reflect the true odds which can be obtained from Table 6. Only rarely in the real world will you have such an opportunity. In the future, always keep in mind that your findings may result as much or even more from sampling variation than from any true association. Even at very low p-values, chance may have produced your findings. Rare events are happening all the time! (11) From Table 6, what are the expected numbers of urban and rural controls in table 7? How might you explain the discrepancy with the number of controls actually selected (table 7)? 14 As it happened, in the initial selection of controls, one case was included in the 116 persons. When this was noted, searching of the lists was resumed at the point where the case was located, and the next person who met the criteria for controls and who was not a case was substituted for them. The control group, therefore, is a sample of non-cases in the population. If the cases had been retained in the sample, however, the groups would not have been a sample of non-cases but rather a sample of the total study population. Table 8 shows a sample of the study population, which in this particular instance happened to include 1 case. Table 8 Residence and grades of school completed for cases of cancer of the colon and a sample of white males and females aged 45 through 64 years who were identified in the 1963 census of Washington County, MD Initial characteristic Cases Sample 116 116 Urban 50 58 Rural 66 58 23 9 93 107 Total Residence 1.00 Grades completed 13+ <13, NS* * NS: Not stated (12) When the cross-products approach used in Table 7 is applied to Table 8, what measure of association is produced? 15 1.00 When cases are compared in this way with a sample of the population, there are no simple ways of obtaining confidence limits. If, however, the disease is rare, the same formula used for confidence limits of relative odds will give limits that are suitable for most practical purposes. A second set of controls matched to the cases was drawn. For each case, a non-case of the same race, sex and year of age was selected. The results are shown in Table 9 as counts of individual controls, not as matched pairs. Table 9 Residence and grades of school completed for cases of cancer of the colon and randomly selected controls matched to cases by race, sex and year of age, white males and females aged 45 through 64 identified in the 1963 census of Washington County, MD Initial characteristic Total Cases Matched Controls 116 116 Relative odds Residence Urban 50 55 Rural 66 61 23 16 93 100 1.00 Grades completed 13+ <13, NS* 1.00 * NS: Not stated (13) Why do the results in Table 9 differ from those in Tables 6 and 7? Which of the two control sets is likely to be most appropriate for the assessment of risk associated with education level attained? Why? 16 While the relative odds calculated in this way (e.g. by pooling matched pairs) yields an estimate that is likely to be closer to the truth than if matching were not done, it is not a socially accepted method. Some epidemiologists and biostatisticians even become rather violent in their objections. With matched controls, a different method of calculating the relative odds should be employed. Not only is the arithmetic simpler, but the resulting odds ratio is unbiased. The table is set up as illustrated in Table 10 for residence. Use the data in Table 11 to obtain the numbers of years of school completed. Table 10 Numbers of pairs of cases of cancer of the colon and matched controls by residence and schooling classification of case and control in each pair Matched controls Cases Relative odds 95% Confidence limits** 0.84 0.50 - 1.40 RESIDENCE Urban Rural Urban 23 (a) 32 (b) Rural 27 (c) 34 (d) GRADES COMPLETED 13+ <13, NS* 13+ <13, NS* * NS: Not stated ** See formula below. 17 Cells "a" and "d" in Table 10, where the residence and schooling histories of cases and controls in each pair agree, are not considered to add any useful information, and are consequently disregarded. The relative odds are calculated by dividing the number of pairs in cell "c" by the number of pairs in cell "b". Note that the total number in all four cells or the two parts of Table 10 is not the number of subjects but the number of matched pairs. Note also that when the table is arranged with case characteristics at the top, the matched pairs odds ratio is c/b, not b/c as in many textbook illustrations where control characteristics are placed at the top. Moral: Don't assume that everyone labels their tables in the same way. For the confidence limits, calculate the variance of the log RO as detailed in your lecture handouts: VAR (ln( ROpaired )) = 1 1 + b c (14) What are the advantages and disadvantages of adjustment by using matched controls? If the value of relative odds calculated by the matched pair method is identical to the value obtained by the pooled method, what does this tell you about the usefulness of matching? The use of matched pairs in this instance would have made it possible to use the method of sequential analysis to stop the study as soon as a relative risk had been found that was significantly different from 1.00 (or any other predetermined value) at any predetermined level of significance. Although sequential analysis is primarily designed for use in therapeutic trials in which the endpoint for each subject is rather quickly determined, there is no reason why the procedure might not be applied to matched case-control studies in order to hold the time and expense of the study to the minimum required for a definitive answer. In Washington County, sequential analysis has been particularly useful when trying out a new interview procedure or questionnaire. In such situations, one wishes to know whether the new represents a significant improvement over the old as quickly as possible. By allocating one of each matched pair of subjects to one procedure and the other subject to the other procedure, one can stop the experiment as soon as a significant answer is obtained -- or when enough pairs have been exposed to the two methods that it is clear that neither has an important advantage. The method is explained in Armitage P: Sequential Medical Trials, Blackwell, 1960, and illustrated in an article by Snell and Armitage in Lancet 1:860, 1957. Another useful article is Bross, I: Sequential medical plans, Biometrics, pp 188-205, Sept. 1952. A few pages from this article are appended (Appendix 1). 18 Table 11 Years of school completed for cases and their matched controls. Pair Case Cont Pair Case Cont Pair Case Cont Pair Case Cont 1 2 3 4 5 9 10 8 7 14 12 8 99 4 14 30 31 32 33 34 12 8 6 10 14 7 11 16 8 8 59 60 61 62 63 3 8 12 6 14 9 8 8 7 18 88 89 90 91 92 6 8 14 12 8 8 8 6 13 4 6 7 8 9 10 8 15 13 8 11 4 9 99 17 15 35 36 37 38 39 9 8 2 11 7 8 8 8 11 12 64 65 66 67 68 8 7 8 12 8 9 6 7 9 0 93 94 95 96 97 4 12 7 8 8 99 5 12 8 8 11 12 13 14 15 8 11 16 20 12 8 12 10 8 5 40 41 42 43 44 10 8 9 12 6 8 12 16 7 12 69 70 71 72 73 8 9 18 8 16 7 8 14 8 6 98 99 100 101 102 12 13 14 9 12 8 11 8 14 6 16 17 18 19 20 12 11 7 10 12 6 12 2 8 12 45 46 47 48 49 10 8 8 12 12 6 16 10 13 7 74 75 76 77 78 8 14 8 8 12 12 8 3 6 9 103 104 105 106 107 10 6 8 8 12 13 11 8 12 10 21 22 23 24 25 10 5 8 16 17 14 6 4 5 6 50 51 52 53 54 12 8 8 12 8 12 8 3 7 8 79 80 81 82 83 5 15 9 16 8 6 8 12 14 6 108 109 110 111 112 10 9 8 7 8 99 9 15 14 12 26 27 28 29 9 12 12 16 7 12 6 11 55 56 57 58 7 8 14 12 6 5 4 12 84 85 86 87 8 13 12 13 12 11 4 7 113 114 115 116 17 11 16 8 8 5 9 8 19 PART III: A SIMPLE TEST FOR THE SIGNIFICANCE OF A LINEAR TREND, TREND CHI-SQUARE Referring again to Part I of this exercise, in 1961, subcutaneous fat thickness was measured on the photofluorographs of 24,390 persons who participated in the 1946 survey in Muscogee County, GA (Comstock, Kendrick, Livesay: Subcutaneous fatness and mortality. Am J Epidemiology 83:548, 1966). Table 12 shows data from this study. Table 12 Tuberculosis mortality during the period 1946-1961 by thickness of fat layer over the trapezius ridge in 1946 among black persons aged 15-34 years in 1946 whose chest photofluorographs showed no evidence of tuberculosis in 1946. Fat Thickness (mm) Midpoint Population Tuberculosis Deaths Number Rate 0-4 1690 14 .00828 5-9 1845 6 .00325 10+ 766 2 .00261 Total 4301 22 .00512 If one applies the usual chi-square test with two degrees of freedom to the above table, one obtains a value of 5.54, equivalent to a p-value of 0.063. Because this p-value falls above the widely esteemed threshold of 0.05, many persons would shrug off such a finding as non-significant. The original hypothesis of the study, however, was that thin people would have higher tuberculosis death rates than fat people. This hypothesis calls for rates to fall in order, with the highest rate for the 0-4 mm fat layer group and the lowest rate for the group with fat layers of 10 mm or more. The ordinary Chi-square test gives the likelihood that chance alone could produce the observed values in any of six different orders. Clearly, the likelihood of getting these rates in the predicted order purely by chance must be appreciably less than getting them in any of six orders. A convenient and widely applicable test for the probability that chance alone could account for obtaining values in a predicted order is given in Statistical Methods by Snedecor and Cochran, 7th Edition, 1990, pp. 204-208 (also Cochran WG: Some methods for strengthening the common χ2 tests. Biometrics 10:434-435, 1954.) The hypothesis to be tested in this case is that the proportion of tuberculosis deaths decreases with increasing fat thickness. Graphically, this would correspond to fitting a straight line through the three points. The hypothesis can be 20 tested by calculating the slope3 of the line and testing whether it is significantly different from 0. The figure below shows the graphical result, and table 13 shows the data presented in table 12, plus additional columns that have been added to facilitate the calculations needed to estimate the slope ß. Note that the three fat thickness categories have been treated as ordinal values and given arbitrary scores -1, 0, and 1 (see below). Table 13 Work table for the calculation of slope ß (data from table 12). Fat Thickness Midpoint Population Tuberculosis Deaths mm. (ni) Number (ai) 0-4 1690 14 5-9 1845 10+ Total Rate (pi) Score (Xi) aiXi niXi niXi2 .00828 -1 -14 -1690 1690 6 .00325 0 0 0 0 766 2 .00261 +1 N = 4301 22 p = .00512 3 Slope (usually denoted as ß) is the average change in the ordinate (rate) of the regression function associated with a unit change in the abscissa (fat thickness). 21 By filling in the work table and using the equations below you can calculate the slope ß, and its standard deviation, Sß. The hypothesis that ß=0 (flat line) can be tested by calculating z, the number of standard deviations that the estimated ß is away from the null hypothesis (ß=0). Z should be normally distributed and its square (z2) should have a chi-square distribution. (15) Fill in the blanks in Table 13. To calculate ß, it is simplest to consider its numerator and denominator separately: NUM = (ai Xi) - (ai) (ni Xi) (22) (-924) = (-12) = - 7.274 N 4301 DEN = (ni Xi2) - = s = z = (ni Xi)2 N = (2456) - (-924 )2 = 2257.49 4301 NUM = - 0.00322 DEN pq = 0.001502 DEN -0 s = - 2.145 , p = 0.032 [Note: ß-0 (beta minus zero) is analogous to O-E (observed minus expected). Beta is the observed slope and 0 is the expected under the null hypothesis being tested.] "z" can be converted into chi-square with 1 degree of freedom: 2 2 1 = z2 = (-2.145 ) = 4.601 (16) What is the meaning of the ß value you calculate? For a trend test, what does a negative value of z signify? (17) Is a statistically significant trend test synonymous with a significant doseresponse trend? 22 Note that the calculation is greatly simplified by selecting the values of X as -1, 0 and +1. Other numbers could be used, such as 1, 2, and 3. Or if one had evidence that group 10+ was much fatter than that order implied, one could choose 1, 2, and 4, if this seemed to be the appropriate progression of fatness. With continuous variables and modern calculators, it is best to use the mean value of each category (category of fat thicknesses in this example). These mean values are 3.1, 7.0 and 14.1 mm. If an order can be predicted ahead of time, and if reasonable numerical values can be attached to the ranking orders, this is a more appropriate test than one that does not take order into account. Snedecor and Cochran state that "moderate differences between two scoring systems seldom produce marked differences in the conclusions drawn from the analysis". Try this out for yourself by letting Xi equal 3.1 for the 0-4 mm group, 7.0 for the 5-9 mm group, and 14.1 for the 10+ mm group. 23 Appendix 1 24 Appendix 1 25