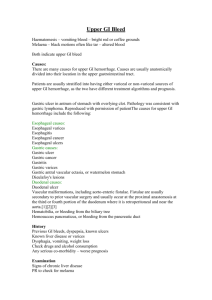

Upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage

advertisement

Upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage Causes Peptic ulcer (50%) Gastric erosions Oesophageal or gastric varices Mallory-Weiss tear Angiodysplasia Dieulafoy malformation Gastric neoplasia Management Patients should be managed according to agreed multidisciplinary protocols Close collaboration between physicians and surgeons is vital Aggressive fluid resuscitation is important Circulating blood volume should be restored with colloid or crystalloid Cross-matched blood should be given when available All patients require closed monitoring Possibly in an HDU or ITU environment with central and arterial pressure monitoring Bleeding peptic ulcer 80% bleeding stops spontaneously 25% require intervention for recurrent bleeding within 48 hours It is difficult to predict those that will continue to bleed All patients require early endoscopy (± intervention) to determine: Site of bleeding Continued bleeding Features of recent bleed o o o o Ooze from ulcer base Clot covering ulcer base Black spot in ulcer base Visible vessel Picture provided by Mohamed Husein, University of Ottawa, Canada Recently shown that proton pump inhibitors may improve the outcome in non-variceal upper GI haemorrhage Endoscopic therapy Laser photocoagulation using the Nd-YAG laser Bipolar diathermy Heat probes Adrenaline or sclerosant injection No technique is superior Comparative trials of different techniques are inconclusive Indications for surgery Continued bleeding that fails to respond to endoscopic measures Recurrent bleeding Patients > 60 years Gastric ulcer bleeding Cardiovascular disease with predictive poor response to hypotension Surgery for bleeding peptic ulcer For duodenal ulcer Create gastroduodenotomy between stay sutures Bleeding usually from gastroduodenal artery Underun vessels with 2/0 nonabsorbable suture on round body needle Avoid picking up common bile duct Close gastroduodenotomy as a pyloroplasty Consider truncal vagotomy and pyloroplasty All patients should be given H. pylori eradication therapy post operatively If a pyloroplasty will be difficult because of large ulcer consider Polya gastrectomy For gastric ulcer Consider either local resection of ulcer or partial gastrectomy Variceal upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage 90% patients with portal hypertension have varices 30% patients with varices will have an upper gastrointestinal bleed 80% of GI bleed in patients with portal hypertension comes from varices The mortality of a variceal bleed is approximately 50% 70% patients will have a rebleed Survival is dependent on the degree of hepatic impairment Primary prevention Bleeding from varices more likely if poor hepatic function or large varices Primary prevention of bleeding is possible with β blockers Reduces risk of haemorrhage by 40-50% Band ligation may also be considered Sclerotherapy or shunting is ineffective Active bleeding Resuscitation should be as for other causes of upper GI haemorrhage Endoscopy should be performed to confirm site of haemorrhage Vasopressin and octreotide decrease splanchnic blood flow and portal pressure Lactulose may be used to decrease GI transit and reduce ammonia absorption Metronidazole and neomycin may be used to reduce gut flora Temporary tamponade can be achieved with Sengstaken-Blackmore tube o Should be considered as a salvage procedure o Tamponade is 90% successful at stopping haemorrhage o Unfortunately 50% patients rebleed within 24 hours of removal of tamponade A Sengstaken-Blackmore tube has three channels o One to inflate the gastric balloon o One to inflate the oesophageal balloon o One to aspirate the stomach Emergency endoscopic therapy includes: o Endoscopic banding of varices o Intravariceal or paravariceal sclerotherapy o Sclerosants include ethanolamine and sodium tetradecyl sulphate If endoscopic methods fail need to consider: o Transection or devascularisation o Porto-caval or mesenterico-caval shunting Emergency shunting associated with 20% operative mortality and 50% encephalopathy Shunting can also be performed non-surgically by transjugular intrahepatic porto-systemic shunting (TIPSS) Reduces risk of rebleeding but increases risk of encephalopathy Mortality of the procedure ~1% Secondary prevention 70% of patients with an variceal haemorrhage will rebleed The following have been shown to be effective in the prevention of rebleeding o Beta-blockers possibly combined with isosorbide mononitrate o Endoscopic ligation o Sclerotherapy o TIPSS o Surgical shunting Bibliography Dagher L, Patch D, Burroughs A. Management of oesophageal varices. Hosp Med 2000; 61: 711717. Ghosh S. Watts D, Kinnear M. Management of gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Postgrad Med J 2002; 78: 4-14. Gotzsche P C. Somatostatin or octreotide for acute bleeding oesophageal varices. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000; 2: CD000103. Gow P J, Chapman R W. Modern management of oesophageal varices. Postgrad Med J 2001; 77: 75-81 Lau J Y W, Sung J J Y, Lee K K C et al. Effects of intravenous omeprazole on recurrent bleeding after endoscopic treatment of bleeding peptic ulcers. N Eng J Med 2000; 343: 310-316. Ohmann C, Imhof M, Roher H D. Trends in peptic ulcer bleeding and surgical management. World J Surg 2000; 24: 284-293. Rosch J, Keller F S. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt: present status, comparison with endoscopic therapy and shunt surgery and future perspectives. World J Surg 2001; 25: 337-346. Sharara A I, Rockey D C. Gastroesophageal variceal hemorrhage. N Eng J Med 2001; 345: 669681. Stabole B E, Stamos M J. Surgical management of gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2000; 29: 189-222.