Chapter 1-7. Looping, Collapsing, and Reshaping

advertisement

Chapter 1-7. Looping, Collapsing, and Reshaping

Looping through variables

We will use the births.dta dataset for this exercise. After modifying the “change directory”, the

“cd” command(s) to match your own directory, we can bring the dataset into Stata using,

clear

cd "C:\Documents and Settings\u0032770.SRVR\Desktop\"

cd "Biostats & Epi With Stata\datasets & do-files"

use births

Suppose you wanted to generate a frequency table, followed by descriptive statistics, for several

variables in the dataset.

To loop through variables, we first need to know the order the variables are arranged in the Stata

browser. We can do this with the describe command or just look at the order in the Variables

window.

describe

Contains data from births.dta

obs:

500

Data from 500 births

vars:

9

20 Mar 2002 10:07

size:

15,500 (99.9% of memory free)

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------storage display

value

variable name

type

format

label

variable label

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------id

float %9.0g

identity number

bweight

float %8.0g

birth weight in grams

lowbw

byte

%9.0g

low birth weight

gestwks

float %9.0g

gestation period

preterm

byte

%9.0g

pre-term

matage

byte

%8.0g

maternal age

hyp

byte

%8.0g

hypertens

sex

byte

%8.0g

sex of baby

sexalph

str6

%9s

sex coded as string

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------Sorted by: id

The variables are listed in the order they are left to right if we looked in the data browser or data

editor. This is the same order they are shown in the Variables window.

Another useful version of the describe command is “describe , simple”, or ds, which just gives

the variable names.

ds

id

bweight

lowbw

gestwks

preterm

matage

hyp

sex

sexalph

____________________

Source: Stoddard GJ. Biostatistics and Epidemiology Using Stata: A Course Manual [unpublished manuscript] University of Utah

School of Medicine, 2011. http://www.ccts.utah.edu/biostats/?pageId=5385

Chapter 1-7 (revision 4 Mar 2011)

p. 1

Example 1. looping through entire variable list.

We don’t need to tabulate the id variable, so we will begin with the second variable and end with

the last variable. We will use a foreach loop.

foreach x of varlist bweight-sexalph {

tab `x'

sum `x'

}

<-- the “x” can be any name we want—it is just a nickname that will be replaced

with actual variable names

<-- the keyword “varlist” informs Stata that a variable list will follow

<-- the “{“ and “}” tell Stata to execute everything in between for each variable

in the varlist. Nothing can follow the opening brace on the first line.

<-- the inward slanting single quote and the apostrophe tell Stata to replace what

is inside with the name of that thing, not its value. Thus for each variable

in turn, the x is replace with the variable name

This foreach loop has the same effect as

tab bweight

sum bweight

tab lowbw

sum lowbw

....

tab sexalph

sum sexalph

Note: In the do-file editor, the line on the left notifies you that you are defining a loop, and it

follows you down the page. You can terminate that action by putting anything but a space after

the termininating brace, “}”. So, you might was well make it an asterik, “*”, which is a comment

that will not produce an error message when you run it in the do-file (safe to just leave it there).

It will look like this,

foreach x of varlist bweight-sexalph {

tab `x'

sum `x'

}

*

Chapter 1-7 (revision 4 Mar 2011)

p. 2

Example 2. looping through non-adjacent variables

describe

Contains data from births.dta

obs:

500

Data from 500 births

vars:

9

20 Mar 2002 10:07

size:

15,500 (99.9% of memory free)

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------storage display

value

variable name

type

format

label

variable label

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------id

float %9.0g

identity number

bweight

float %8.0g

birth weight in grams

lowbw

byte

%9.0g

low birth weight

gestwks

float %9.0g

gestation period

preterm

byte

%9.0g

pre-term

matage

byte

%8.0g

maternal age

hyp

byte

%8.0g

hypertens

sex

byte

%8.0g

sex of baby

sexalph

str6

%9s

sex coded as string

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------Sorted by: id

This time, let’s only use bweight through preterm plus sex. In the variable list, we can mix and

match the “through”, the “-” specifier, with just listing individual variables.

foreach x of varlist bweight-preterm sex {

tab `x'

sum `x’

}

foreach x of varlist bweight-preterm sex {

tab `x'

sum `x'

}

A feature to help you create this variable list is a macro called “r(varlist)”, which is created, or

returned, by the describe or ds command. To see this, use return list after the describe.

ds

return list

. ds

id

bweight

lowbw

gestwks

preterm

matage

hyp

sex

sexalph

. return list

macros:

r(varlist) : "id bweight lowbw gestwks preterm matage hyp sex sexalph"

Chapter 1-7 (revision 4 Mar 2011)

p. 3

So, just use,

ds

display r(varlist)

id bweight lowbw gestwks preterm matage hyp sex sexalph

Highlight this output with the mouse, and copy-and-paste it into the do-file editor after

foreach x of varlist to help you build the loop.

Example 3. Turn scrolling off, saving output to log file, and printing the log file

In the previous two examples, the scrolling feature was bothersome, so we might want to turn it

off.

Also, if we have a long list of variables, the beginning of the output will be erased from the Stata

Results window memory and we won’t be able to look at it.

Finally, we might want to print the output.

set more off // turn scrolling off

log using junk.smcl, replace

// start logging to file

foreach x of varlist bweight-preterm sex {

tab `x'

sum `x'

}

log close

// stop logging to a file

set more on // turn scrolling back on

*

print junk.smcl // print log file to the Windows default printer

To look at the output in the log file, click on the scroll icon (4th from left) on the Stata menu bar.

Chapter 1-7 (revision 4 Mar 2011)

p. 4

Looping Over Numbers

We will use a simple example that has no research significance, just to learn the looping

structure.

Let’s display the numbers 1, 3,4,5, 10, 15, 20, and 100, along with the numbers squared.

We could use,

foreach num of numlist 1 3/5 10(5)20 100 {

display `num' _column(10) `num'*`num'

}

*

1

3

4

5

10

15

20

100

1

9

16

25

100

225

400

10000

The “3/5” gave us every integer between 3 and 5.

The “10(5)20” gave us the numbers between 10 and 20, incrementing by 5.

The “_column(10)” was tab to column 10.

Other options for the display command can be found using,

help display

A partial list is:

_skip(#)

_column(#)

_newline

_newline(#)

_continue

skips # columns

skips to the #th column

goes to a new line

skips # lines

suppresses automatic newline at end of display command

Chapter 1-7 (revision 4 Mar 2011)

p. 5

If you want to loop over a large number of equally spaced numbers, a more efficiently executed

looping syntax is,

forvalues x = 1/10 {

display `x' _column(10) `x'*`x'

}

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

1

4

9

16

25

36

49

64

81

100

Inner and Outer Loops

Looping can be nested to as many levels as you desire. To create a multiplication table for

numbers one to three, we could use the following,

* -- multiplication table: attempt 1

* r = row , c = col

forvalues r = 1/3 {

forvalues c = 1/3 {

display "`r' x `c' = " `r'*`c'

}

}

1

1

1

2

2

2

3

3

3

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

1

2

3

1

2

3

1

2

3

=

=

=

=

=

=

=

=

=

1

2

3

2

4

6

3

6

9

Notice that the outer loop, with the r counter, gets set to a value. Then the inner loop runs

through all of its numbers. Then the outer loop increments to its next value, and so on.

The display always ends with a carriage return, or newline, unless instructed not to.

Chapter 1-7 (revision 4 Mar 2011)

p. 6

Let’s put the result in a square matrix.

* -- multiplication table: attempt 2

* r = row , c = col

forvalues r = 1/3 {

forvalues c = 1/3 {

display `r'*`c' " " _continue

}

}

1 2 3 2 4 6 3 6 9

The suppressing of the newline, using “_continue” remained in effect, even though we went back

out to the outer loop.

To fix that,

* -- multiplication table: attempt 3

* r = row , c = col

forvalues r = 1/3 {

forvalues c = 1/3 {

display `r'*`c' " " _continue

}

display // display nothing goes to next line

}

1 2 3

2 4 6

3 6 9

Notice that this square matrix is symmetric around the main diagonal, with the “2 3 6” in the

upper right corner and in the lower left corner.

To eliminate the duplicates, so that we display just an upper triangular matrix,

* -- multiplication table (upper triangular matrix): attempt 1

* r = row , c = col

forvalues r = 1/3 {

forvalues c = `r'/3 {

display `r'*`c' " " _continue

}

display // display nothing goes to next line

}

1 2 3

4 6

9

Chapter 1-7 (revision 4 Mar 2011)

p. 7

We got the right numbers, it just that we need to tab over to the right appropriately. To do that,

we add the following two lines between the forvalues statements:

* -- multiplication table (upper triangular matrix): attempt 2

* r = row , c = col

forvalues r = 1/3 {

local m=(`r'-1)*2

display _skip(`m') _continue

forvalues c = `r'/3 {

display `r'*`c' " " _continue

}

display // display nothing goes to next line

}

1 2 3

4 6

9

Here a we used a “local macro”, which can be a scalar or matrix. It only exists inside a program

or do-file. If you go out to the Command window and try to use it, it will not be found.

Looping Over Strings

To loop over names, or string constants, that have no embedded spaces, we could use,

foreach x in Joe Mary Bill {

display "My name is " "`x'"

}

My name is Joe

My name is Mary

My name is Bill

The double quotes are required by the display command to display a string. The inner single

special quotes, `x’, mean evaluate the macro and insert it’ contents right at that position, as if you

had typed in the contents yourself from the keyboard.

If the list has embedded spaces, use quotes around the strings,

foreach x in "Joe Brown" "Mary Jones" "Bill Smith" {

display "My name is " "`x'"

}

My name is Joe Brown

My name is Mary Jones

My name is Bill Smith

Chapter 1-7 (revision 4 Mar 2011)

p. 8

While Loops

If we do not know in advance the range of numbers to loop over, a while loop structure is better.

It has the syntax:

while exp {

stata commands

}

The looping continues until the expression is no longer true.

Here is a simple example,

local x=0

while `x' < 5 {

local x=`x'+1

display `x'

}

1

2

3

4

5

Notice it was necessary to initialize x (assign it a starting value) before entering the while loop.

Then, inside the loop, it needs to eventually change to a value that evaluates to false in the while

expression; otherwise, the loop will continue indefinitely (called an infinite loop).

Chapter 1-7 (revision 4 Mar 2011)

p. 9

Scalars and Local Macros

In the preceding while loop, we used a “local macro”, which was a scalar (a matrix with one

element) that exists only in a program or do-file which uses it.

To illustrate

local x=0

while `x' < 5 {

local x=`x'+1

display `x'

}

display "x = " `x'

1

2

3

4

5

. display "x = " `x'

x = 5

Now, in the Command window, which is outside of the do-file, execute the following line

display "x = " `x'

. display "x = " `x'

x =

.

We see that x did not have a value outside of the do-file. It simply evaluated as a blank macro.

Chapter 1-7 (revision 4 Mar 2011)

p. 10

A scalar, on the other hand, exists for the entire Stata session, inside or outside of the do-file or a

program. Using a scalar this time,

scalar x=0

while x < 5 {

scalar x=x+1

display x

}

display "x = " x

1

2

3

4

5

. display "x = " x

x = 5

From the Command window,

display "x = " x

. display "x = " x

x = 5

.

Notice that a scalar does not need the special single quotes around it. Those are used to evaulate

a macro. A scalar is actual just a variable with one number. It also continues to exist outside of

the do-file, or program, and remains until Stata is exited, or you use,

scalar drop x

The choice between local macros or scalars is largely just a user personal preference.

Chapter 1-7 (revision 4 Mar 2011)

p. 11

Working with Multiple Observations Per Subject: Row calculations across several

variables (means, sums, etc).

Let’s suppose we have 3 systolic blood pressure readings per patient.

clear

input id sex sbp0 sbp15 sbp30

1 0 120 125 128

2 1 123 118 .

end

list

+---------------------------------+

| id

sex

sbp0

sbp15

sbp30 |

|---------------------------------|

1. | 1

0

120

125

128 |

2. | 2

1

123

118

. |

+---------------------------------+

If all we wanted to do was compute a mean of these three blood pressures to use as a new

variable in our analysis, we might try:

capture drop meansbp

gen meansbp=(sbp0+sbp15+sbp30)/3

list

+--------------------------------------------+

| id

sex

sbp0

sbp15

sbp30

meansbp |

|--------------------------------------------|

1. | 1

0

120

125

128

124.3333 |

2. | 2

1

123

118

.

. |

+--------------------------------------------+

Notice that Stata used was is called listwise deletion of missing values in this computation. That

is, if any of the variables have a missing value, the generated variable is set to missing.

What we want, however, is to compute the mean for the second subject as

gen meansbp=(sbp0+sbp15)/2 if id==2

We wouldn’t to it this way, however. A better approach is to use:

capture drop meansbp

egen meansbp = rowmean(sbp0 sbp15 sbp30)

// compute row mean omitting missing values

list

+--------------------------------------------+

| id

sex

sbp0

sbp15

sbp30

meansbp |

|--------------------------------------------|

1. | 1

0

120

125

128

124.3333 |

2. | 2

1

123

118

.

120.5 |

+--------------------------------------------+

This time we get the correct result, where the function rowmean sums the nonmissing

observations and divides by the correct number of nonmissing observations.

Chapter 1-7 (revision 4 Mar 2011)

p. 12

Use help egen to see a long list of such row functions, for computing sums, minimum,

maximums, etc.

The egen command (extension to generate) is a generate command that only works using the

functions that are specific to this command.

Reshaping the Data Structure

In some statistical packages, such as SPSS, the software expects the data to be arranged in wide

data structure. In most other statistical packages, such as Stata, SAS, MLwiN, S-Plus, and

Spida, the software expects the data to be arranged in long data structure for some commands.

Wide data structure

id

1

2

sex

0

1

sbp0

120

123

sbp15 sbp30

125

128

118

.

sex

0

0

0

1

1

sbp

120

125

128

123

118

Long data structure

id

1

1

1

2

2

time

0

15

30

1

15

Generally, Stata only requires the long format if we are using regression models for longitudinal

(repeated measurements) data, or if we have several measurements on the same individuals

which are not necessarily in any time order.

In Stata, we can switch from one structure to the other using the reshape command.

Chapter 1-7 (revision 4 Mar 2011)

p. 13

We will start with the dataset with a wide structure.

clear

input id sex sbp0 sbp15 sbp30

1 0 120 125 128

2 1 123 118 .

end

list

+---------------------------------+

| id

sex

sbp0

sbp15

sbp30 |

|---------------------------------|

1. | 1

0

120

125

128 |

2. | 2

1

123

118

. |

+---------------------------------+

To convert this to long structure, we use

reshape long sbp, i(id) j(time) // convert to long structure

list

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

+-----------------------+

| id

time

sex

sbp |

|-----------------------|

| 1

0

0

120 |

| 1

15

0

125 |

| 1

30

0

128 |

| 2

0

1

123 |

| 2

15

1

118 |

|-----------------------|

| 2

30

1

. |

+-----------------------+

In this command, the “sbp” is called the stub variable (prefix variable would be a more intuitive

name). Stata used the j subscript variable, time, to store the suffix that followed “sbp” in the

variable names.

Stata used the i subscript variable to identify what variable identifies each subject. This variable

has to contain a unique number across the rows of data, or it will get confused (see box).

It then just duplicated the values of all the other variables in the file and placed them on each

newly created row.

Chapter 1-7 (revision 4 Mar 2011)

p. 14

What happens if i( ) variable is not unqiue for each observation (each row).

* -- intentional error -preserve

clear

input id sex sbp0 sbp15 sbp30

1 0 120 125 128

1 1 123 118 .

end

list

reshape long sbp, i(id) j(time)

list

restore

// will crash because id not unique

. reshape long sbp, i(id) j(time)

(note: j = 0 15 30)

i=id does not uniquely identify the observations;

there are multiple observations with the same value of id.

Type "reshape error" for a listing of the problem observations.

r(9);

The do-file crashes because Stata needs to have a unique value for every row for the i( ) variable.

You can quickly create such a variable using the “_n” variable, which is Stata’s internal variable

for observation number, or row number, in the data editor/browser. Use this in a generate

statement before the reshape command, like so:

preserve

clear

input id sex sbp0 sbp15 sbp30

1 0 120 125 128

1 1 123 118 .

end

list

gen id2 = _n

list

reshape long sbp, i(id2) j(time)

list

restore

+---------------------------------------+

| id

sex

sbp0

sbp15

sbp30

id2 |

|---------------------------------------|

1. | 1

0

120

125

128

1 |

2. | 1

1

123

118

.

2 |

+---------------------------------------+

Chapter 1-7 (revision 4 Mar 2011)

p. 15

With our data currently in long format,

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

+-----------------------+

| id

time

sex

sbp |

|-----------------------|

| 1

0

0

120 |

| 1

15

0

125 |

| 1

30

0

128 |

| 2

0

1

123 |

| 2

15

1

118 |

|-----------------------|

| 2

30

1

. |

+-----------------------+

if we wanted to convert this to wide structure, we would use

reshape wide sbp, i(id) j(time) // convert to wide structure

list

+---------------------------------+

| id

sbp0

sbp15

sbp30

sex |

|---------------------------------|

1. | 1

120

125

128

0 |

2. | 2

123

118

.

1 |

+---------------------------------+

This time, Stata took the value in the j( ) subscribe variable and appended it to the prefix we

specified in the stub variable, sbp.

Chapter 1-7 (revision 4 Mar 2011)

p. 16

Working with Multiple Observations Per Subject: Column calculations across several

observations (means, sums, etc).

Put the data back into long structure:

reshape long sbp, i(id) j(time)

list

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

+-----------------------+

| id

time

sbp

sex |

|-----------------------|

| 1

0

120

0 |

| 1

15

125

0 |

| 1

30

128

0 |

| 2

0

123

1 |

| 2

15

118

1 |

|-----------------------|

| 2

30

.

1 |

+-----------------------+

This time, we use the following to compute the mean SBP:

capture drop meansbp

bysort id: egen meansbp=mean(sbp)

list

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

+----------------------------------+

| id

time

sbp

sex

meansbp |

|----------------------------------|

| 1

0

120

0

124.3333 |

| 1

15

125

0

124.3333 |

| 1

30

128

0

124.3333 |

| 2

0

123

1

120.5 |

| 2

15

118

1

120.5 |

|----------------------------------|

| 2

30

.

1

120.5 |

+----------------------------------+

Notice Stata ignored the missing value and calculated the mean based on the number of

nonmissing observations. That is what we wanted.

Chapter 1-7 (revision 4 Mar 2011)

p. 17

Tagging multiple observations per subject in long format

Given our data are on six rows (six observations), Stata will think we have a sample size of 6.

Actually, we only have a sample size of 2.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

+----------------------------------+

| id

time

sbp

sex

meansbp |

|----------------------------------|

| 1

0

120

0

124.3333 |

| 1

15

125

0

124.3333 |

| 1

30

128

0

124.3333 |

| 2

0

123

1

120.5 |

| 2

15

118

1

120.5 |

|----------------------------------|

| 2

30

.

1

120.5 |

+----------------------------------+

If we asked for a frequency table, then, we would get

tab meansbp

meansbp |

Freq.

Percent

Cum.

------------+----------------------------------120.5 |

3

50.00

50.00

124.3333 |

3

50.00

100.00

------------+----------------------------------Total |

6

100.00

One approach to insuring the correct sample size is used is to create a tag variable.

egen tag = tag(id), missing

list

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

+----------------------------------------+

| id

time

sbp

sex

meansbp

tag |

|----------------------------------------|

| 1

0

120

0

124.3333

1 |

| 1

15

125

0

124.3333

0 |

| 1

30

128

0

124.3333

0 |

| 2

0

123

1

120.5

1 |

| 2

15

118

1

120.5

0 |

|----------------------------------------|

| 2

30

.

1

120.5

0 |

+----------------------------------------+

The tag function of the egen command tags one observation in each distinct group of the varlist

egen tag = tag(varlist)

The result is 1 or 0, according to whether the observation is tagged, and never missing.

When the missing option is specified,

egen tag = tag(varlist), missing

Chapter 1-7 (revision 4 Mar 2011)

p. 18

the first observation of a distinct group of varlist is still tagged, even if the group is all missing.

To use this tag variable, simply include if tag in any command you want to limit the analysis to

the actual sample size.

tab meansbp if tag

// limit to tagged observations

meansbp |

Freq.

Percent

Cum.

------------+----------------------------------120.5 |

1

50.00

50.00

124.3333 |

1

50.00

100.00

------------+----------------------------------Total |

2

100.00

Notice we can use “if tag”, instead of “if tag==1” if we want to, and we still get the same result.

tab meansbp if tag==1

// same thing

meansbp |

Freq.

Percent

Cum.

------------+----------------------------------120.5 |

1

50.00

50.00

124.3333 |

1

50.00

100.00

------------+----------------------------------Total |

2

100.00

If a variable is given in an if statement, without an expression, stata interprets it as “true” if a

nonzero value is found. In this case we get the right result, which we always do with the tag

variable. However, you have to be careful with this shortcut for other variables. Stata stores

missing values as a “very large number”, or + for all practical purposes. So, if we take this

shortcut for a variable that has missing values, it selects those observations as well.

list if sbp // shortcut method

list if sbp~=. // better to just use this safer method

. list if sbp

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

// shortcut method

+-----------------------------+

| id

time

sex

sbp

tag |

|-----------------------------|

| 1

0

0

120

1 |

| 1

15

0

125

0 |

| 1

30

0

128

0 |

| 2

0

1

123

1 |

| 2

15

1

118

0 |

|-----------------------------|

| 2

30

1

.

0 |

+-----------------------------+

. list if sbp~=. // better to just use this safer method

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

+-----------------------------+

| id

time

sex

sbp

tag |

|-----------------------------|

| 1

0

0

120

1 |

| 1

15

0

125

0 |

| 1

30

0

128

0 |

| 2

0

1

123

1 |

| 2

15

1

118

0 |

+-----------------------------+

Chapter 1-7 (revision 4 Mar 2011)

p. 19

Collapsing Long Format

Alternatively, we could simply collape the dataset down to one observation per subject.

Starting over:

clear

input id sex sbp0 sbp15 sbp30

1 0 120 125 128

2 1 123 118 .

end

reshape long sbp, i(id) j(time)

list

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

+-----------------------+

| id

time

sex

sbp |

|-----------------------|

| 1

0

0

120 |

| 1

15

0

125 |

| 1

30

0

128 |

| 2

0

1

123 |

| 2

15

1

118 |

|-----------------------|

| 2

30

1

. |

+-----------------------+

We want the ID to go to its unique value

time to just drop out of the collapsed dataset

sex to go to its unique value

sbp to go to its mean

collapse sex (mean) sbp, by(id)

list

+---------------------+

| id

sex

sbp |

|---------------------|

1. | 1

0

124.3333 |

2. | 2

1

120.5 |

+---------------------+

Variables, such as time, which are not specified on the collapse command are simply dropped.

All variables preceding the ( ) are reduced to their mean by default, so this was the same thing as

collapse (mean) sex sbp, by(id)

All variables following a ( ) have the operation performed on them, such as (mean), (sum), or

(max).

The by( ) defines “over each unique value” in the by-list.

Note: Be sure you save your dataset before you do this, or at least can easily recreate it using

your do-file—alternative, you can use preserve and restore to un-collapse.

Chapter 1-7 (revision 4 Mar 2011)

p. 20

Preserve and Restore

If you want to get your data back to the state it was before the collapse, use preserve and restore.

Starting with the original dataset in long format,

clear

input id sex sbp0 sbp15 sbp30

1 0 120 125 128

2 1 123 118 .

end

reshape long sbp, i(id) j(time)

list

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

+-----------------------+

| id

time

sex

sbp |

|-----------------------|

| 1

0

0

120 |

| 1

15

0

125 |

| 1

30

0

128 |

| 2

0

1

123 |

| 2

15

1

118 |

|-----------------------|

| 2

30

1

. |

+-----------------------+

This time we will preserve the data before we collapse, and then restore it afterwards.

preserve // save copy of data in this original state

collapse sex (mean) sbp, by(id)

list

restore // restore data into original state

list

. preserve // save copy of data in this original state

. collapse sex (mean) sbp, by(id)

. list

+---------------------+

| id

sex

sbp |

|---------------------|

1. | 1

0

124.3333 |

2. | 2

1

120.5 |

+---------------------+

. restore

. list

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

// restore data into original state

+-----------------------+

| id

time

sex

sbp |

|-----------------------|

| 1

0

0

120 |

| 1

15

0

125 |

| 1

30

0

128 |

| 2

0

1

123 |

| 2

15

1

118 |

|-----------------------|

| 2

30

1

. |

+-----------------------+

Chapter 1-7 (revision 4 Mar 2011)

p. 21

Example (graphs with error bars)

One possible use of the collapse command is to draw graphs with error bars.

use births, clear

sum gestwks

Variable |

Obs

Mean

Std. Dev.

Min

Max

-------------+-------------------------------------------------------gestwks |

490

38.72186

2.314167

24.69

43.16

We see that gestational has two decimal places, so we will need to round it to the nearest week.

If we went to the help for egen, we would not find the round function. To find it, search the help

for “functions”. You will see a help screen that looks like:

help functions

[D] functions -- Functions in expressions

Quick references are available for the following types of functions:

+----------------------------------------------------------------+

| Type of function

| See help

|

|--------------------------------------+-------------------------|

| Mathematical functions

| math functions

|

|

|

|

| Probability distributions and

|

|

|

density functions

| density functions

|

|

|

|

| Random-number functions

| random-number functions |

|

|

|

| String functions

| string functions

|

|

|

|

| Programming functions

| programming functions

|

|

|

|

| Date and time functions

| dates and times

|

|

|

|

| Selecting time spans

| time-series functions

|

|

|

|

| Matrix functions

| matrix functions

|

|

|

|

+----------------------------------------------------------------+

Click on math functions, which will give you a long list of functions:

Mathematical functions

abs(x)

Domain:

Range:

Description:

-8e+307 to 8e+307

0 to 8e+307

returns the absolute value of x.

. . .

round(x,y) or round(x)

Domain x:

-8e+307 to 8e+307

Domain y:

-8e+307 to 8e+307

Range:

-8e+307 to 8e+307

Description: returns x rounded in units of y or x rounded to the nearest

integer if the argument y is omitted.

Chapter 1-7 (revision 4 Mar 2011)

p. 22

All functions in Stata work with the generate, or gen, command, except for the very small list of

functions you find listed when you search on egen.

We create a rounded gestational age variable using,

gen rndgestwks=round(gestwks)

tab rndgestwks

rndgestwks |

Freq.

Percent

Cum.

------------+----------------------------------25 |

1

0.20

0.20

27 |

2

0.41

0.61

28 |

2

0.41

1.02

31 |

6

1.22

2.24

32 |

3

0.61

2.86

33 |

5

1.02

3.88

34 |

6

1.22

5.10

35 |

9

1.84

6.94

36 |

21

4.29

11.22

37 |

34

6.94

18.16

38 |

84

17.14

35.31

39 |

107

21.84

57.14

40 |

128

26.12

83.27

41 |

66

13.47

96.73

42 |

14

2.86

99.59

43 |

2

0.41

100.00

------------+----------------------------------Total |

490

100.00

We see that there is too little data for gestational ages outside of the 36 to 41 weeks range,

particularly if we produce a graph separately for male and female fetuses.

To make sure we can get back to our original data, since we will immediately return to other

analyses, we could type the following in the do-file, and then do our graph work inside this

preserve-restore block. (Alternatively, we could just read the data back in later, which is usually

just as easy.)

* -- begin graph

preserve

restore

* -- end graph

Let’s begin by limiting the dataset to weeks 36 to 41.

keep if rndgestwks>=36 & rndgestwks<=41

tab rndgestwks

rndgestwks |

Freq.

Percent

Cum.

------------+----------------------------------36 |

21

4.77

4.77

37 |

34

7.73

12.50

38 |

84

19.09

31.59

39 |

107

24.32

55.91

40 |

128

29.09

85.00

41 |

66

15.00

100.00

------------+----------------------------------Total |

440

100.00

Chapter 1-7 (revision 4 Mar 2011)

p. 23

We are going to apply the same formula for a 95% CI that the t-test output uses, so that we can

check our work. Doing this for week 41,

ttest bweight if rndgestwks==41, by(sex) // use to check our work

Two-sample t test with equal variances

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------Group |

Obs

Mean

Std. Err.

Std. Dev.

[95% Conf. Interval]

---------+-------------------------------------------------------------------1 |

35

3589.057

72.47286

428.7552

3441.775

3736.34

2 |

31

3352.742

62.90985

350.2672

3224.263

3481.221

---------+-------------------------------------------------------------------combined |

66

3478.061

50.28804

408.542

3377.628

3578.493

---------+-------------------------------------------------------------------diff |

236.3152

97.15402

42.22775

430.4027

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------diff = mean(1) - mean(2)

t =

2.4324

Ho: diff = 0

degrees of freedom =

64

Ha: diff < 0

Pr(T < t) = 0.9911

Ha: diff != 0

Pr(|T| > |t|) = 0.0178

Ha: diff > 0

Pr(T > t) = 0.0089

We will use this output momentarily.

Now we collapse the data by sex to get means, standard deviations, and sample sizes, which we

will need to compute 95% confidence intervals.

collapse (mean) mbw=bweight (sd) sdbw=bweight ///

(count) nbw=bweight, by(rndgestwks sex)

list , abbrev(15)

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

+-------------------------------------------+

| sex

rndgestwks

mbw

sdbw

nbw |

|--------------------------------------------|

|

1

36

2693.09

348.534

11 |

|

2

36

2655.5

532.578

10 |

|

1

37

2840.55

496.511

20 |

|

2

37

2834.5

332.788

14 |

|

1

38

3195.75

529.639

40 |

|--------------------------------------------|

|

2

38

2870.05

450.433

44 |

|

1

39

3307.76

453.279

59 |

|

2

39

3262.83

309.326

48 |

|

1

40

3447.01

500.553

70 |

|

2

40

3290.69

417.706

58 |

|--------------------------------------------|

|

1

41

3589.06

428.755

35 |

|

2

41

3352.74

350.267

31 |

+--------------------------------------------+

Notice this time we used variable names to store the results into, rather than just keeping the

original variable name, which was done in the preceding example.

Now, we could construct a confidence interval around the mean using the large sample normal

approximation confidence interval (CI),

mean 1.96 SE.

Chapter 1-7 (revision 4 Mar 2011)

p. 24

However, a more appropriate CI is constructed from the t-distribution, rather than the normal

distribution (1.96 bounds the middle 95% of the normal distribution). The t-test output uses a CI

constructed from the t-distribution. For small sample sizes, the 1.96 approach gives an interval

that is too narrow. For infinite sample sizes, the two approaches are identical.

We do this by replacing 1.96, which comes from the standard normal distribution, with the value

of the t distribution, for our given sample size, that provides the middle 95% of the area under the

t distribution curve.

gen bwlcl=mbw-invttail(nbw-1,0.025)*sdbw/sqrt(nbw)

gen bwucl=mbw+invttail(nbw-1,0.025)*sdbw/sqrt(nbw)

list , abbrev(15)

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

+------------------------------------------------------------------+

| sex

rndgestwks

mbw

sdbw

nbw

bwlcl

bwucl |

|------------------------------------------------------------------|

|

1

36

2693.09

348.534

11

2458.943

2927.239 |

|

2

36

2655.5

532.578

10

2274.517

3036.483 |

|

1

37

2840.55

496.511

20

2608.176

3072.925 |

|

2

37

2834.5

332.788

14

2642.354

3026.646 |

|

1

38

3195.75

529.639

40

3026.363

3365.137 |

|------------------------------------------------------------------|

|

2

38

2870.05

450.433

44

2733.101

3006.99 |

|

1

39

3307.76

453.279

59

3189.637

3425.888 |

|

2

39

3262.83

309.326

48

3173.014

3352.652 |

|

1

40

3447.01

500.553

70

3327.662

3566.367 |

|

2

40

3290.69

417.706

58

3180.86

3400.52 |

|------------------------------------------------------------------|

|

1

41

3589.06

428.755

35

3441.775

3736.34 |

|

2

41

3352.74

350.267

31

3224.263

3481.221 |

+------------------------------------------------------------------+

Comparing this to the t-test output for week 41 above,

Two-sample t test with equal variances

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------Group |

Obs

Mean

Std. Err.

Std. Dev.

[95% Conf. Interval]

---------+-------------------------------------------------------------------1 |

35

3589.057

72.47286

428.7552

3441.775

3736.34

2 |

31

3352.742

62.90985

350.2672

3224.263

3481.221

---------+-------------------------------------------------------------------combined |

66

3478.061

50.28804

408.542

3377.628

3578.493

---------+-------------------------------------------------------------------diff |

236.3152

97.15402

42.22775

430.4027

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------diff = mean(1) - mean(2)

t =

2.4324

Ho: diff = 0

degrees of freedom =

64

Ha: diff < 0

Pr(T < t) = 0.9911

Ha: diff != 0

Pr(|T| > |t|) = 0.0178

Ha: diff > 0

Pr(T > t) = 0.0089

We see that our calculations were correct.

We now have the data set up for constructing the graphs. We could have run a bunch of ttests to

get these numbers and then inputted them back in to set up the data for graphing. The collapse

way is just more automated.

Chapter 1-7 (revision 4 Mar 2011)

p. 25

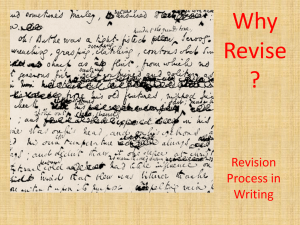

To get a line graph with 95% CI error bars, we use

3000

Males

2500

Females

2000

birthweight (kg)

3500

4000

capture drop rndgestwks2

gen rndgestwks2=rndgestwks+0.1 if sex==2

sort rndgestwks

#delimit ;

twoway (line mbw rndgestwks if sex==1, clcolor(blue) lwidth(*1.5))

(line mbw rndgestwks2 if sex==2, clcolor(green) lwidth(*1.5))

(rcap bwucl bwlcl rndgestwks if sex==1, lwidth(*1.5)

lcolor(blue) msize(*1.5))

(rcap bwucl bwlcl rndgestwks2 if sex==2, lwidth(*1.5)

lcolor(green) msize(*1.5))

, legend(off)

xtitle("gestational age (weeks)")

ytitle("birthweight (kg)")

text(3400 37.5 "Males" )

text(2700 38.75 "Females" )

;

#delimit cr

36

Chapter 1-7 (revision 4 Mar 2011)

37

38

39

gestational age (weeks)

40

41

p. 26