Assignments and Exercises

advertisement

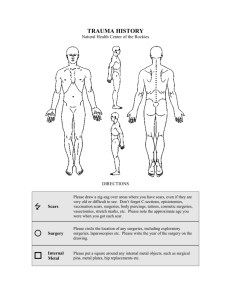

Section Eight: Bodies Learning Objectives To understand how women’s bodies are socially constructed. To be familiar with the ways that race, ethnicity, class, and sexuality affect women’s access to health care, how women see their bodies, and their treatment by the heath industry. To be aware of the hierarchies embedded in the medical establishment and how this affects women’s health care body image. Section Summary Although physical bodies and health may seem to be purely biological, they are also socially constructed. Cultural ideologies affect how we understand our own physical bodies. Social institutions like politics, medicine, and the media shape women’s access to health care and healthy work conditions and shape the way women see themselves. Women’s bodies are often the site of political contestation and control, and feminists have often focused on changing health policies. Historically the healthcare industry viewed women’s bodies as abnormal and diseased. The women’s health movement challenged the way medicine treated women and assisted women in reclaiming control over their bodies. Today this movement must focus on new technologies and work alongside other movements. Race, class, religion, nationality, and sexuality intersect with gender to socially construct women’s bodies. Reading 37: Anne Fausto-Sterling, “The Bare Bones of Sex: Part 1- Sex and Gender” Fausto-Sterling is a biologist who uses human bone (structure, density, propensity to break, etc.) as an example of the complicated interconnected relationship of nature and nurture in shaping human bodies and experience. She introduces a life-course dynamic systems approach to the analysis of sex/gender which suggests that bodies are shaped by various and dynamic social processes as well as by genes and hormones. Fausto-Sterling suggests that to understand the body and to ward off disease we must recognize that we are both 100% nature and 100% nurture at all times. Sterling begins with examples that demonstrate how lived experiences resulting from cultural eating habits, occupation, exercise routine, race, and geographic location likely shape bones. Feminists, particularly those in the social sciences, and biologists must understand the body to be simultaneously made up of genes, hormones, organs, and cells as well as culture and history which ALL influence both health and behavior. Although feminists have attempted to separate sex and gender and have focused on gender as determined by culture, Sterling points to research in disability studies which bring the body back into the picture. IM | 65 In medicine, and biological psychology, scientists continue to examine how biological sex determines a number of gender behaviors and thus creates differences between the sexes. Many of those interested in this work are feminists, such as the Society for Women’s Health Research, who are attempting to bring gender equity to the healthcare system, but they fail to understand the role of culture in shaping the body. Fausto-Sterling examines bones because of the long history of the use of bones to understand history and because problems with bones such as diseases demonstrate the difficulty of defining sex apart from gender. Claims about gender differences in osteoporosis are dependant upon our definition of the disease. Most studies and doctors rely on bone mineral density tests which are cheap and have been promoted by drug companies, and this has replaced older diagnoses which relied on broken bones. However, volumetric measures and knowledge of bone strength may better determine one’s risk of osteoporosis. How and why men and women’s bone density differs at various points in the life-cycle is still not well understood as scientists do no understand the role of hormones or of culture in shaping our bones. A dynamic systems approach doesn’t just look at parts of the body by themselves, but rather looks to understand issues by looking at the whole. In a figure Fausto-Sterling demonstrates how physical activity, diet, drugs, bone formation in fetal development, hormones, bone cell metabolism, and biomechanical effects of bone formation can be analyzed as a complex system. Each of these systems relates to each other and produce bodies that either develop osteoporosis or not. Reading 38: Becky Wangsgaard Thompson, "’A Way Outa No Way:’ Eating Problems among African-American, Latina, and White Women” Interviews with a diverse group of lesbians and women of color demonstrate that, for many women, eating problems are related to trauma. We must understand the diverse causes of eating problems in order to find help for those women who are at the intersection of multiple axes of oppression. Women who are lesbian, poor, or non-white experience eating disorders that cannot be primarily linked to the media-constructed “culture of thinness.” Many women who experience eating problems trace the onset of these problems to oppression in the form of sexual abuse, racism, classism, heterosexism, and sexism. Some of these women experienced multiple traumas that contributed to their problem. Sexual abuse, which was the most common trauma these women experienced, left the women feeling out of control or needing to change or punish their bodies. Poverty and heterosexism caused stress that food helped these women forget. Some minority women were pressured to make their bodies different in order to aid their families’ assimilation into a higher class standing. For these women, their relationship with food was a way to regain control over their lives or to anesthetize the pain of their trauma or oppression. The traumas distorted women’s views of their own bodies and blocked their ability to feel connected to their bodies. Reading 39: Simone Weil Davis, “Loose Lips Sink Ships” IM | 66 Davis explores the construction of the “problem” of an abnormal labia which can be corrected with cosmetic surgeries that provide women with “designer vaginas” through labiaplasty. She argues that this surgery and other vaginal surgeries like female genital mutilation should be seen on a continuum that involves a more complex understanding of the choices and cultural constraints involved in the surgeries. Labiaplasty is a cosmetic procedure that involves cutting labial tissue or injecting fat into the labia in order to correct “excessively droopy” or “abnormal” labia. Doctors and patients seek minimal, unextended, symmetrical, and pink labia that are “not wavy.” Although most American women are happy with their genitalia, this surgery creates new fears and self-consciousness for women about their bodies: are their labia normal? Cosmetic surgery uses medical language and classical aesthetics to secure modern credibility for their construction of an “ideal” body and genitalia. Labiaplasty helps women obtain the idealized airbrushed or altered (fake) body. Current vaginal surgeries derive from a history of Western culture that has pathologized women’s sexuality and sexual organs and whose constructions of women have vacillated between modesty and lustiness, often with racist conceptions of the “other” women. o Western doctors performed legal vaginal surgeries to “cure” women of various “problems” through the 1970’s with at least one doctor performing them illegally through the 1980s. o Today the genitalia of intersex children are also altered without their consent in order to force the body to conform to cultural ideals of gender. o Racism, classism, and sexism affected how doctors treated colonized women and who they practiced surgeries on. Western opposition to female genital operations (FGO) in African females is often ethnocentric and oversimplified. o Although African women have less resources to keep their bodies from the public gaze, this procedure is very similar to Western cosmetic vaginal surgeries. o While FGOs are outlawed in the United States very similar surgeries performed by Western doctors are not. o Cultural and social ideas of what is desired in women manufacture consent for both procedures. Vaginal surgeries have various meanings. African FGO can hold cultural, religious and even meaning. o Women who receive both types of surgeries are primarily seeking beautification, transcendence of shame, and conformity. o The preferred look following both FGO and labiaplasty is the “clean slit.” o Women are not just duped by males into having this surgery. Rather, women’s own agency plays an important role in constructing the “need” for both of these surgeries by encouraging other women to undergo surgery. Although this surgery does nothing to actually help women, the cosmetic surgery industry has appropriated feminist language and practices in order to encourage women to feel they are independently choosing to have the surgery. The industry has appropriated the women’s movements’ discourse of self-knowledge, choice/ independence, community building/self-help, and increasing the medical community’s responsiveness to women. Finally, Davis encourages women to “speak back” to these constructions of abnormal female sexuality and sexual organs, and she applauds those who do so. IM | 67 Reading 40: Andrea Smith, “Beyond Pro-Choice versus Pro-Life: Women of Color and Reproductive Justice” Reproductive justice is better understood from outside the dichotomy between pro-life and prochoice. Smith demonstrates how both of these arguments uphold and mask racial hierarchies and capitalism, and both positions do little to support women of color. The pro-life position maintains that a fetus is a life and concludes that abortion should be criminalized and people should be penalized with imprisonment. Smith questions the usefulness of criminalization as a response to this issue. Criminalization would contribute to the prison-industrial complex that disproportionately hurts minorities and the poor. Prisons are the modern method used to control these populations. In addition, prisons do not decrease (and could increase) crime rates, but they do take resources away from other institutions that could more effectively address social issues. The criminal justice system’s intervention into women’s issues like domestic violence and rape has not been successful. Smith suggests that those in the pro-life camp pay close attention to other Christian evangelicals who have questioned the efficacy of the criminal justice system. She also suggests that the pro-choice position should also come from an anti-prison position, particularly since many poor and minority women are having their pregnancies criminalized. The pro-choice position rests on an individualist and consumerist notion of choice, rather than on a system of rights which are benefits available to all. Choices are limited by the social, economic, and political conditions surrounding people. Reproductive “choices” are often very limited for poor and minority women. The prochoice position only guarantees reproductive choices to women who can afford them and who are seen as able to make “good choices.” Pro-choice groups have often supported dangerous or potentially dangerous contraceptives and rejected informed consent for nonwhite or poor women. Many pro-choice organizations have racist histories and allies. Historically, Planned Parenthood collaborated with the eugenics movement to reduce the poor and minority population. Today pro-choice organizations are often aligned with organizations that attempt to reduce population growth. These organizations blame poor women for the problems of population growth and have often sterilized women in foreign countries without their consent. This focus on population eliminates women’s choices rather than expands them. Additionally, the pro-choice camp often has a single-issue political agenda that promotes other structures of repression for women, particularly women of color. Both the pro-choice and the pro-life positions assume a criminal justice framework for focusing on reproductive issues, both reinforce racist and sexist hierarchies, and both do not question the capitalist system. Smith suggests that we need to search for the causes of many of the problems facing women in order to fully ensure reproductive justice. Smith suggests that women of color need to engage in base-building work in order to argue for social institutions that will better serve the reproductive rights of all women. Reading 41: Barbara Ehrenreich, “Welcome to Cancerland” IM | 68 As a survivor herself, Ehrenreich angrily criticizes the “pink-ribbon marketplace” and “cult of the breast-cancer survivor” that normalizes the experiences of breast cancer to the point that having breast cancer is presented as positive and the causes of the disease are ignored. Cancer, a group of cells that multiply so rapidly that they eventually destroy the body they inhabit, is a lot like the runaway social processes in human life. Although breast-cancer is no longer a disease kept secret, the rate of survival from breast cancer is littler better today than in the 1930s. Today’s breast-cancer patients can find an overwhelming amount of information on the process of breast-cancer, but this information is almost always packaged in cheery, survivor-as-hero, language. Those who feel anger or other emotions are typically marginalized in the big machinery of the modern breast-cancer world. The pink-ribbon marketplace offers thousands of “feminine” products that often support breast-cancer research or survivors. Many of the products infantilize the women who have breast-cancer. The mainstream breast-cancer movement has adopted several aspects of feminism, like self-help groups, without actually incorporating any feminist ideology or a critical awareness of the causes of the disease. However, feminist organizations focus on causes and prevention. One of the suspected causes is environmental carcinogens. Corporate sponsors would not be so willing to “support” the breast-cancer movement if it attacked the environmental problems of industrialization. Those who have lived through the disease are called “survivors” and these women (and a few men), are heralded by the movement instead of those who died from the disease. The breast cancer culture feels like a cult to Ehrenreich because it enforces cheerfulness and prohibits dissent. Much of the breast-cancer culture seems to positively embrace the disease for its redemptive powers and “opportunities for self-improvement” or at least self-transformation. Critics of the of the mainstream breast-cancer movement suggest that its activities are inefficient ways to find cures for breast-cancer and instead promote the corporate sponsors and the breast cancer industry. The movement claims that this all raises awareness about the disease, but the awareness has done little to decrease rates of cancer or increase early detection. The breast-cancer cult is complicit in global poisoning because it encourages women to suspend judgment, follow their doctors’ advice, and see cancer as a positive experience. However, multinational corporations benefit from polluting the environment with cancercausing agents and from expensive cancer treatments that are painful and rarely extend the life of the women who undergo treatment. Boxed Insert: Eli Clare, “Stolen Bodies, Reclaimed Bodies: Disability and Queerness” Justice movements like the disability rights movement have disentangled the body from society’s treatment of disabled bodies, but Clare points out that the body is a necessary aspect of oppression and identity. Cultures have often suggested that disabled bodies, or queer bodies or other nonhegemonic bodies, are “wrong.” The disability rights movement suggests that the focus should not be on the body, but rather on unjust cultural treatment of the disabled. This has shifted the focus away from the physical body and locates the problem within culture’s ableism, or disability oppression, rather than within the disabled person. IM | 69 Clare reclaims the disabled body by suggesting that people pay attention to their physical forms and celebrate the differences of physical bodies. If bodily differences and difficulties are not discussed, activists will not be able to transform their culture. Discussion Questions Reading 37: Anne Fausto-Sterling, “The Bare Bones of Sex: Part 1- Sex and Gender” 1. What are the problems with current thinking by feminist social scientists about gender and sex? What is wrong with how medical scientists look at this issue? 2. What are some examples of how culture shapes our bones? 3. What are the seven systems that Fausto-Sterling identifies as being important for bone density and development? How do these systems relate to each other? Reading 38: Becky Wangsgaard Thompson, "’A Way Outa No Way:’ Eating Problems among African-American, Latina, and White Women” 4. What have many feminists claimed is the reason for eating disorders? What did Thompson find was the cause? 5. How are traumas and oppressions related to eating disorders? How is food used? How does trauma cause women to feel about their bodies? 6. What needs to change in order to stop eating disorders? Reading 39: Simone Weil Davis, “Loose Lips Sink Ships” 7. What is a labiaplasty? What look are most women trying to achieve with this surgery? 8. Why do the women say they had this surgery? What are the cultural reasons that Davis says that women have the surgery? 9. How is a labiapsty similar to female genital mutilation? How is it different? What power differences exist between the African women and the American women? Do you see these surgeries as similar? Why or why not? 10. How has the medical industry co-opted feminist language and practices in order to encourage women to have a labiaplasty? What do you think this says about out culture? 11. What can women do to stop disturbing trends in cosmetic surgeries and FGM? Reading 40: Andrea Smith, “Beyond Pro-Choice versus Pro-Life: Women of Color and Reproductive Justice” 12. What are the main problems with the pro-life position according to Smith? What are the problems with the pro-choice position? 13. How are the pro-life and the pro-choice positions similar? How do both of these positions treat poor or minority women? 14. How can a new political focus on reproductive justice be constructed in a way that does not oppress minority or poor women? Reading 41: Barbara Ehrenreich, “Welcome to Cancerland” IM | 70 15. How does Ehrenreich describe the mainstream breast-cancer movement and her experiences of cancer? Why does she call it a cult? 16. Why is she critical of this movement? What are her major complaints about the way this culture treats women? Do you think this culture helps women and cancer patients in general? Why or why not? 17. How does the feminist movement react differently to breast-cancer organizing? 18. What does Ehrenreich suggest is a probable cause of breast-cancer? Why does the movement not focus on this cause? What consequences does this have for women? Boxed Insert: Eli Clare, “Stolen Bodies, Reclaimed Bodies: Disability and Queerness” 19. How has the disability movement treated bodies? Why does Eli Clare want to reclaim the body? 20. How is the treatment of the queer body and the disabled body similar? Why do you think Clare includes both types of bodies in the title? Assignments and Exercises Women’s Health Movement: In order for students to understand the implications of the exclusion of most women of color and poor women from the historical women’s health movement, ask students to write a short paper on one aspect of the women’s health movement that carefully looks at race or class. Topics may include eugenics and the birth-control movement, the exclusion of forced sterilization from the concerns of the movement, the location of abortion or birth-control clinics, the rare attention paid to the restrictive costs of reproductive health, etc. Ask students to conclude by suggesting ways that the problem they have studied should be addressed in the current women’s health movement. Ignoring Women in Modern Health Care: In order to explore how medicine today continues to use the male body as the standard and to treat women’s health needs as less important, ask students to research an aspect of the modern health-care system that is gendered. They should describe their findings to the class and relate them to one or more readings. Suggested topics: (a) (b) (c) (d) drugs and medical procedures being rarely tested on women; the continuing ignorance of women’s experiences with heart disease and other illnesses that are regularly associated with men but that also affect many women; health insurance coverage of Viagra but not of birth control; abortions or procedures to help women become pregnant rarely being covered by health insurance. The Medicalization of Women’s Bodies: This exercise will allow students to explore how medicine has attempted to control women’s bodies in the United States. Ask students to research both arguments regarding issues such as: PMS, menopause, caesarian births, hospital births versus homebirths, higher rates of bariatric surgeries (or gastric bypasses) for women, or IM | 71 infertility. Ask them to describe whether the condition is seen as an existing problem and what treatments/solutions are available. Body Rituals: Ask students to list the ways that people work on their bodies, whether for pleasure, for strength, or for social acceptability. (Start the list with things such as sports and exercise, hair dye, makeup, cosmetic surgery, etc.) Ask students which of these body rituals are more closely associated with males and which are more closely associated with females. After sorting the body rituals into two separate lists, ask students how the male body rituals are different from the female body rituals and what implications this has for women and men. Media Portrayals of Women’s Bodies: This exercise is designed to have students think about the media’s role in the social construction of women’s bodies. Ask students to explore the portrayal of women’s bodies in advertising, film, or popular television programming. The paper should explore what these images suggest about the ideal female body and how these images contribute to poor body image for many women. Additionally, the paper should focus on how race, class, and sexuality are portrayed. Students should look for the following: (a) (b) (c) How are women of color portrayed differently from white women (what aspects of their bodies are focused on)? When are the women shown large rather than thin? Are women shown as strong or weak? Explaining Eating Problems: Eating disorders are prevalent on most college campuses, and this exercise is designed to aid students in the fight against this gendered problem. Invite a studenthealth nurse or someone from a local campaign against eating disorders to come to class and discuss how eating disorders ravage women’s bodies and what signs to look for in oneself, friends, or relatives. Ask this person to describe the possible causes of eating disorders and to explain why more women than men are affected. Later, discuss what the guest lecturer had to say in the context of what students learned from reading Becky Wangsgaard Thompson’s reading. Film on Body Image: Advertising images of women create a powerful context in which women learn to equate the purchase of products with the possibility of being beautiful according to the terms defined by the fashion industry. The documentary The Strength to Resist: Media's Impact on Women and Girls can be shown in class to demonstrate the sexual objectification of women in advertising, its affect on men and women, and people’s abilities to resist these influences. More information on the film, including a curriculum guide can be found at: http://www.cambridgedocumentaryfilms.org/Resist.html Variety of genital surgeries: Simone Weil Davis (39 “Loose Lips Sink Ships”) explores the expansion of cosmetic surgery into surgeries that are performed on women’s genitals and how the Western surgeries are similar to African female genital cuttings, older practices of female circumcisions in Western cultures, and surgeries performed on intersex children (described in greater detail in Reading 7). Since Davis’s writings additional Western female genital surgeries have gained in popularity such as revirgination where a hymen is repaired so that it could be retorn during sex. In addition, feminists have begun to explore the social construction of surgeries IM | 72 performed on male genitals like the commonly accepted practice of circumcision or more recent penis enlargement surgeries. Explore these topics in greater detail during class by assigning students to groups and asking each group to prepare a presentation for the class on one of these surgeries. Ask them to explore the pros and cons of each surgery. Web Links AdiosBarbie Satire can be the best medicine. Check out the AdiosBarbie website, which provides a cheeky look at body issues. You can play “Feed the Model” just for fun! http://www.adiosbarbie.com/ Alternative Medicines Many Americans use some form of “alternative medicine”—from massage to St. John’s Wort to using yogurt to treat yeast infections. Why might alternative medicine appeal especially to women? Does alternative medicine pose risks to those who use it? Does it pose risks to the profits of the pharmaceutical industry? Visit this National Institutes of Health website on alternative medicine and think about these issues. http://nccam.nih.gov/ Breast-Cancer Sites Women’s breast health constitutes a major concern in women’s health care. Visit these sites to explore the mainstream wisdom regarding breast health. Thinking about the criticisms of Barbara Ehrenreich (41 “Welcome to Cancerland”), discover for yourself the atmosphere of these sites and what is missing (such as information on causes of breast-cancer) from their discussion of the disease. Susan G. Komen for the Cure http://cms.komen.org/komen/index.htm Breast Cancer Connections http://www.bcconnections.org/ BreastCancer.Org http://www.breastcancer.org/ Eating Disorders Women in Western industrialized countries have suffered from an epidemic of eating disorders over the last twenty years. Are anorexia and bulimia cultural, psychological, organic, or genetic? Why do they afflict women more than men—and why are women on the verge of adolescence most vulnerable? Explore these issues on-line through this website. http://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/p.asp?WebPage_ID=337 The Eugenics Movement The eugenics movement in the United States resulted in the forced sterilization of both women and men identified by physicians or social workers as “mentally defective,” insane, or constitutionally undesirable. Between 1910 and 1940 the Cold Springs Harbor Laboratory, a genetics research institute in the state of New York, housed the Eugenics Research Office which was the central research facility of the American eugenics movement. Today this laboratory, once closely affiliated with the eugenics research, displays an on-line archive of the eugenics movement in order to demonstrate the pseudo-science and cultural prejudices involved in eugenics. IM | 73 http://www.eugenicsarchive.org/eugenics/ Feminist Women’s Health Care The second wave of the feminist movement inspired the formation of women’s health centers across the country. Such centers have provided women with education, support, and health care from a perspective that supports a woman’s right to make her own decisions about sexuality, reproduction, and allopathic and alternative medical approaches to treating medical problems. The Feminist Women’s Health Center, which emerged from the women’s health movement, continues to provide feminist-based medical care and education to women with clinics in several locations and education available via the internet. http://www.fwhc.org/ Forced Sterilization Forced sterilization of minority women occurs in a number of places around the world. One research report based on 230 in-depth interviews with Roma women in eastern Slovakia, documented this atrocity in Eastern Europe. Additionally, the forced sterilization of Native American and other women continues to be of major concern. Review the following websites to learn more about the forced sterilization of minority and poor people. http://www.womensenews.org/article.cfm/dyn/aid/1243 http://www.ratical.org/ratville/sterilize.html http://againsttheirwill.journalnow.com/ http://www.sptimes.com/News/111101/Worldandnation/Human_weeds.shtml The Long Battle to Include the Concerns of Women of Color in Reproductive Rights Feminists of color have worked to include the topic of “forced sterilization” into the feminist movement since the second-wave began. This site provides historical information on sterilization of minority women and an early plea that the women’s movement should address this issue. http://www.cwluherstory.com/CWLUArchive/cesa.html National Organization to Halt the Abuse and Routine Mutilation of Males (NO HARMM) This website explores in depth the common practice of male circumcision. NO HARMM is a network that seeks to educate people about the risks of male genital surgeries and the social construction of the normalcy of these surgeries. This network sees many similarities between female genital operations and male circumcision and seeks to end both practices. http://www.noharmm.org/home.htm Organizations for Size/Fat Acceptance A number of organizations are involved in a social movement to change societal attitudes towards individuals who are thought to be above average size in contemporary Western societies. These organizations challenge discrimination and prejudice against these people. National Association to Advance Fat Acceptance http://www.naafa.org/documents/brochures/naafa-info.html#whatis International Size Acceptance Association http://www.size-acceptance.org/mission.html IM | 74 Our Bodies Our Selves Our Bodies Our Selves has provided three generations of women with helpful, woman-centered information and advice about bodies, health, and health care. Visit their website to find out more about this feminist health-care institution. http://www.ourbodiesourselves.org/ The Society for Women’s Health Research Fausto- Sterling mentions this organization as in Reading 37 as an organization dedicated to “gender-based medicine.” This organization takes part in lobbying, research, and advocacy focused on improving women’s health. http://www.womenshealthresearch.org/site/PageServer The Strength to Resist: Media's Impact on Women and Girls Advertising images of women create a powerful context in which women learn to equate the purchase of products with the possibility of being beautiful according to the terms defined by the fashion industry. The documentary The Strength to Resist: Media's Impact on Women and Girls can be shown in class to demonstrate the sexual objectification of women in advertising, its affect on men and women, and people’s abilities to resist these influences. More information on the film, including a curriculum guide can be found at: http://www.cambridgedocumentaryfilms.org/Resist.html The Vagina Monologues To say the word “vagina” aloud—privately or in public—still constitutes a radical act in many places. Eve Ensler’s award-winning play The Vagina Monologues has helped to end the silence and shame around women’s bodies and sexuality by speaking the previously unspeakable. College campuses across the country have staged the show, which is based on hundreds of “vagina interviews” with women in several countries. Visit this website to read about the Monologues and learn how they have become a Valentine’s Day tradition across the globe. http://www.vaginamonologues.com/index.html Women and Heart Disease Heart disease kills more women every year than all cancers combined, yet many women believe that this is a “man’s” disease. Explore this site to get more information on how women can prevent or reduce heart disease. http://www.womenheart.org/ Women and HIV/AIDS Women are vulnerable to HIV/AIDS infection and to misdiagnosis because the symptoms of infection in women differ from those of HIV infection in men. Visit the website of The Body: An AIDS and HIV Information Resource and find out more about women and HIV/AIDS. http://www.thebody.com/whatis/women.shtml IM | 75