Chap006

advertisement

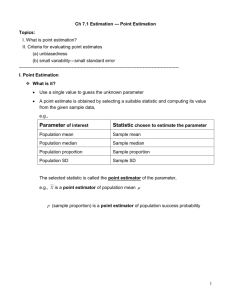

6. Sampling Distributions 6.1 Introduction When a population is large, it would be difficult and costly to measure every item in the population to calculate parameters such as the population mean or the population variance. Instead, we take a random sample from the population, calculate relevant sample statistics and infer the population parameters from the sample statistics. Note that the word parameter is used to denote a characteristic of a population and statistic is used to denote a characteristic of a sample. A random sample is one where every item in the population is given equal chance of being included in the sample. All the sampling results we are going to see are valid only if the sample is random. The first thing to note is that a sample statistic is a random variable. If we take two different samples from the same population we would almost always get two different, hence random, sample means. Although the sample mean is random, intuition tells us that it would not be too different from the population mean. In this chapter, we shall see exactly how sample statistics such as the sample mean are distributed. We denote the population size by N, the population mean by , and the population standard deviation by . We denote the sample size by n, the sampled values by x1, x2, ..., xn, the sample mean by X , and the sample standard deviation by S. See Figure 6.1.1. With these notations we can say that X is an estimator of , and S is an estimator of . Parameters: Population Size = N Mean = Standard Deviation = Statistics: Sample Size = n Mean = X Standard Deviation = S Figure 6.1.1. Notations 6.2 Sampling Distributions By sampling distribution, we mean the distribution of a sample statistic when random samples are drawn from a population. We shall study the sampling distribution of three statistics, namely, the sample mean, the sample proportion and the sample variance, 6.2.1 Sample Mean Suppose we take a random sample of size n from a population of size N. Consider the sum of the n items in the sample (call it sample sum). Because the sample is random, each item x in the population has n/N chance of being selected, and thus will contribute (n/N)x to the sample sum. This makes the expected value of the sample sum equal (n/N) times the population sum, which works out to n. Dividing this by n we get the expected value of sample mean as . Because the expected value of sample mean is equal to the population mean, we call X an unbiased estimator of . Next we shall consider the variance of X . The variance of each sampled item is 2, and since they are all independent the variance of their sum is n2. To get the variance of sample mean we divide this by n2 and get 2/n. Thus the variance of sample mean is 1/n-th of the population variance. This means the variance will decrease as n increases, and for this reason we say X is a consistent estimator of . The most striking result in sampling theory is that as n increases, the distribution of X will approach the normal distribution. This is known as the Central Limit Theorem (CLT), and it is the reason 32 for predominant use of normal distribution in sampling theory. By the CLT, for large n, X ~ N(, 2/n). For this purpose, an n value of 30 or more is considered large. Furthermore, if the population is normally distributed, then n need not be large for the sample mean to be normally distributed. In this case, for all values of n, X ~ N(, 2/n). The template for this case is shown in Figure 6.2.1. Figure 6.2.1. Template for Sample Mean Distribution [Workbook: Sampling.xls; Sheet: Sample Mean Distn.] The Car Mileage example from the textbook has been solved on this template by entering the population mean of 31 in cell C3, substituting the sample standard deviation of 0.7992 in place of population standard deviation (this is possible only when n is large), and entering the sample size of 49 in cell C5. Upon entering 31.553 in cell F13, the probability of the sample mean exceeding 31.553 is displayed in cell H13. It is 0.0000, or almost zero. 6.2.2 Sample Proportion Figure 6.2.2. Template for Sample Proportion Distribution [Workbook: Sampling.xls; Sheet: Sample Proportion Distn.] 33 Suppose a large population consists of p proportion of successes and (1 p) proportion of failures. We take a random sample of size n and find x number of them to be successes. We then calculate the proportion of successes in the sample (call it the sample proportion) denoted by p as x/n. What are the expected value and variance of p ? We note that x will be binomially distributed and therefore its mean is np and variance is np(1 p). Since p = x/n, its expected value is p and variance is p(1 p)/n. Because its expected value is equal to the true value and its variance decreases as n increases, p is an unbiased and consistent estimator of p. Problems concerning p can be solved using the template shown in Figure 6.2.2. The Cheese Spread case of Bowerman/O'Connell has been solved on this template by entering the population proportion 0.1 in cell C3 and the sample size 1000 in cell C4. Upon entering 0.063 in cell F13 the probability of the sample proportion being less than or equal to 0.063 appears in cell G13. It is 0.0000, or almost zero. 6.2.3 Sample Variance In the case of the sample variance S2, when the population is normally distributed, the statistic 2 2 (n1)S / will follow a chi-square distribution with (n 1) degrees of freedom. Chi-square distribution is considered in detail in a later chapter. 6.3 Desirable Properties of Estimators When the expected value of an estimator is equal to the true value, we call it an unbiased estimator. We have seen that both the sample mean and sample proportion are unbiased estimators. An estimator is efficient if its variance is small. Among all unbiased estimators of X is the most efficient. It is therefore the best estimator of . An estimator is consistent if its probability of being close to the parameter it estimates increases as the sample size increases. Because X is unbiased and its variance, 2/n decreases as n increases, it is consistent. Similarly, the sample proportion p is an unbiased and consistent estimator of the population proportion. An estimator is sufficient if it makes use of all the information in the data. Since X is calculated using all the sampled values, it is sufficient. 6.4 Exercises 1. Do the exercises 6-33 and 6-34 in the textbook. 2. Do the exercises 6-40 and 6-42 in the textbook. 6.5 Projects 1. A useful feature in the Analysis ToolPak for sampling is the Sampling command. Open the template Sampling.xls and select the sheet named "Sample". It contains some data in the range A4:A204, and this range has been named Data. To create the first sample seen there, the following actions were taken. Choose Data Analysis... under the Tools menu. In the dialog box that appears choose the Sampling command. In the next dialog box that appears, enter Data in the Input Range box. In the Sampling Method section, choose Random and enter 3 for Number of Samples. In the Output options section select Output Range and enter C4 in the box. Click the OK button. A random sample of 3 numbers are chosen from the data and displayed in the range C4:C8. a. Repeat these steps to produce seven more samples. Calculate the eight sample means. Calculate the mean and standard deviation of these eight sample means. b. Create eight samples of size 10. Calculate the eight sample means. Calculate the mean and standard deviation of these eight sample means. Compare and comment on the results in a. and b. above in light of the sampling theory discussed in this chapter.