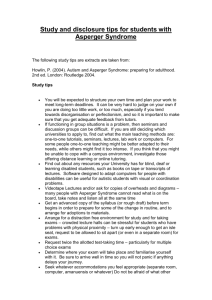

an evaluation of strategies to enable students with asperger`s

advertisement

REAL services to assist students

who have Asperger syndrome

Nicola Martin

Sheffield Hallam University Autism Centre

1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Foreword by Professor Alan Hurst

Abstract

Introduction for Students

Introduction for Parents

Introduction for Practitioners

1. Objective of the Study

2. Literature Review

2.1 Characteristics of AS

2.2 The process of diagnosis

2.3 The effects of AS, with consideration to their potential impact in HE

2.4 Prevalence, gender and changes over time

2.5 Mechanisms for Supporting Students with AS in HE

2.6 Pre HE Experience

2.7 Coping with Change

2.8 Curriculum Versus Support

2.9 Support in HE

2.10 Staff Development

2.11 Critical Review Indicating Gaps in the Literature

3. Purpose

4. Results

Tables

5. General Conclusions

6. REAL Services to Assist University Students who have AS-Good Practice

Guidelines for staff

7. Suggestions for further study

References

3

4

5

6

7

9

11

11

13

17

23

25

27

29

32

34

37

38

39

48

49

77

80

96

98

2

Foreword by Professor Alan Hurst

Sometimes those working to support disabled students in higher education have become

frustrated and disillusioned by what might be perceived to be slow progress. However, as we

approach the end of the first decade of the twenty first century, some progress has been

made. The number of students declaring that they have an impairment either on entry or

during their time in higher education has grown year by year, although in some institutions

and within them in some faculties and departments there is still the need to improve

participation rates. At the level of policy and provision, there has been a shift in focus since

the mid 1990’s. From access and increasing numbers which appeared to be the major focus

of the first national survey of disabled students in universities by the National Innovations

Centre in 1974, the major concern has become the quality of the higher education

experience, especially in learning, teaching, and assessment. This can be demonstrated by

considering the projects and initiatives supported by the national higher education funding

councils.

There is also the need to consider differences in participation rates based on the nature of the

impairment. Compared to the past, in more recent times there has been a growth in the

number of students declaring an impairment such as Asperger syndrome. Because of this,

there is a need for advice and help to be made available for staff working to support these

students in post-compulsory education, for the students themselves, and probably too for their

families. This briefing is a creditable attempt to begin to fill the gap in current knowledge. Not

only does it offer hints on how staff and students might work together effectively, it also

provides some important data deriving from research which might

be used as empirical evidence to support policies and provision. This could be helpful in our

efforts to ensure that services for disabled students are seen as an important core activity for

our universities and colleges rather than as an optional source of additional expense.

I feel honoured to be invited to contribute this short foreword to the briefing. The publication of

the briefing is timely in relation to greater familiarity with the legal requirements regarding

discrimination, and also in relation to both the review of policy and provision for disabled

students since 1997 being undertaken by the Higher Education Funding Council for England

and the revision of the Quality Assurance Agency’s Code of Practice Section 3: Students with

Disabilities. I hope that it is well-received throughout the sector both in the UK and beyond

and that it is the start of a series of publications which explore challenges faced when

ensuring the disabled students are included fully in every aspect of post-compulsory

education.

Alan Hurst (Professor)

formerly of the Department of Education and Social Sciences, University of Central

Lancashire, Preston PR1 2HE

April 2008

3

Abstract

Students with Asperger syndrome (AS) are appearing in greater numbers each year in UK

universities. AS is an autistic spectrum condition, which can result in often subtle differences

in aspects of social behaviour, communication and application of mental flexibility. Young men

in their early twenties from A level backgrounds appear most commonly, mostly in science

based courses and students often demonstrate a high level of application and dedication.

In order to maximise opportunities for success, staff delivering a range of services, need to

have some understanding of AS in general and individual requirements in particular. The

findings of this study illustrate that preparation is routinely minimal, and frequently crucial

people are totally unprepared.

179 staff from 17 disparate English universities shared their experience of effective and

ineffective support strategies based on working with109 learners. Eight students and the

mothers of three provided further insight.

Results indicated that students benefited from institutional and parental assistance to deal

with stress and anxiety caused by social and practical aspects of university life. Backup from

agencies beyond the university rarely featured. Application of knowledge across contexts,

problem solving skills, and organisational difficulties were found to impact most on academic

performance.

Students tended to grow in confidence if services were delivered reliably. Empathising with

the learner's perspective, anticipating anxiety triggers and working in a logical fashion yielded

most satisfactory results. Timetabled sessions with a range of people providing assistance

with specific practical or academic tasks was found to be most effective, particularity when

boundaries were made explicit, and over reliance on one staff member was avoided.

Respect for individuality, guarding against stereotyping, and emphasising the positive, are

essential characteristics of effective practitioners.Good Practice Guidelines, designed to be of

practical use to those committed to helping students to succeed, emphasise the requirement

for services to be REAL.

REAL stands for:

Reliable

Empathic

Anticipatory

and Logical

4

Introduction for Students

The aim of this research is to provide staff who work with university students who have

Asperger syndrome (AS) with useful strategies which are likely to be effective in facilitating

student success.

A small number of students who have AS have provided information directly about services

they have found helpful. However, the research is based mainly on insights from practitioners

who have worked with students who have the condition. Therefore, in the main, the views of

students are reported indirectly, i.e. this is partly about how staff perceive students who have

AS to have reacted to aspects of university life. Clearly the focus on the views of practitioners

can be seen as a weakness of the study. However, the strength of the work is that it provides

practical guidance to staff with the aim of improving their ability to empathise with students

who have AS and therefore potentially to provide better services.

Background information is provided for practitioners about how the university environment in

its broadest sense may affect students who have AS. Strategies to minimise negative impacts

and accentuate the positive are explored. Throughout, individuality is emphasises and the

requirement to understand that no two students with AS are the same runs as a theme.

A social model ethos underpins advice about the development of effective services. That is to

say that encouraging practitioners to think about ways to make adjustments to aspects of

the environment to make it more conducive to the learner styles of students with AS is seen

as far more appropriate than expecting learners to attempt to modify there own behaviour

constantly in order to fit in. This thinking contrasts with the medical model approach to

disability which would locate ‘the problem’ with the person with AS who would be expected to

change in order to fit in to the HE environment as it is set up for neurotypical (NT)students.

The author argues strongly for the need for university staff to empathise with students with

AS, as individuals, and to develop sufficiently imaginative and flexible approaches, to

maximise opportunities for success.

Further research which locates the views of the student as the central focus and follows

learners with AS through university is already underway (Madriaga et al 2008). Ensuring the

prominence of the student voice is in keeping with the most recent update of the Disability

Discrimination Act, The Disability Equality Duty (2006) which places a responsibility on

universities to ensure that authentic student views directly inform improvements in practice.

This study may provide Madriaga, and others, with some useful background.

5

Introduction for Parents

The information arising from this briefing is aimed at enabling practitioners in higher education

(HE) to be better equipped to provide effective individualised services to enable students who

have Asperger syndrome (AS) to succeed.

The views of three mothers and eight students have informed the research but university staff

who fulfil a range of roles have provided the bulk of the information. Their insights are based

largely on experiences of working with learners who have AS. Information gathered in the

study has been used to develop good practice guidelines which are applicable to all aspects

of the university context.

The fact that this work is looking at the bigger picture around university life, rather than

focussing solely on academic success should provide some reassurance to parents who may

often find it difficult to trust practitioners to be sensitive to their son or daughter as a whole

person. Parents may find it helpful to read this briefing in order to gain an insight into the sort

of advice practitioners are working with, and the nature of services available in HE for

students with AS.

Responses from students have clearly illustrated the fundamental importance of parental

support in the majority of instances. Ways of working with parents which take into account the

relationship of the university with the student, first and foremost, are considered here.

Difficulties which can arise, for example around working within the context of data protection

and gaining informed consent from the student to talk to the parent, are discussed. The

relationship between the student and the university is central to the context of this study but

the complexities of parenting a person with AS as they progress into, through and beyond HE

are not overlooked.

Students have often exceeded parental expectations and parents have rarely received any

support with moving on with the young person. Sometimes mothers and fathers have

struggled with the notion of trusting university personnel to provide adequate services. The

aim of making this briefing available to parents is to attempt to supply evidence of the

excellent backup universities could offer. This should provide some reassurance as well as

some empowerment.

Further research which explores parent-offspring relationships, in the context of university

students who have AS, is planned. The need to develop this theme has been identified

because the difficulties of getting the balance right between acknowledging the supporting

role of the parents, and the adult status and developing independence of the student, have

come into sharp focus through this study.

6

Introduction for Practitioners

Research which has informed the good practice guidelines which form part of this study has

focussed mainly on the experience of practitioners in working with students with AS.

The term 'practitioner' is used in this study to describe any member of staff who comes into

contact with students with AS at university. The study indicated that staff development,

designed to enable practitioners to provide more effective services for students with AS, often

excludes front line staff. People who work in residential services for example, can be key to

facilitating a successful university experience for someone with AS.

Staff should have the background information presented here made available to them in

order to further their understanding of the possible impact of AS in the HE context.

Stereotypical ideas about AS should be avoided and the requirement to treat people with the

condition as individuals is paramount.

Early reliable support, and an empathic rather than judgemental approach, has been

demonstrated to be key determinants of success. University life is defined as being broader

than academic experience. Providing individualised assistance to enable the student with AS

to achieve social inclusion, and greater independence, is seen here as being within the remit

of university staff.

A social model ethos is advocated, with the onus being on practitioners to develop the

flexibility to make the environment more conducive. Often simple adjustments have proved to

be very effective. Seeing students with AS as an important part of a diverse community is

advocated as an alternative to expecting them to modify their behaviour significantly in order

to fit in. The research cites numerous examples of empathic, imaginative and flexible backup

provided to students with AS by university staff.

The Disability Equality Duty may be useful as a tool to further develop universities as inclusive

organisations, better equipped to enable students who have AS to achieve their often

considerable potential. Developing the confidence and expertise of all staff is critical to the

aim of achieving a culture of inclusive practice.

7

General Introduction

Brief Outline of the Study

Asperger syndrome (AS) is a form of autism associated with more able people, of at least

average intelligence, and, given the opportunity, potentially capable of benefiting from a

university education.

A recent significant increase in the number of disabled students in UK universities is well

documented by annual data from The Higher Education Statistical Agency (HESA). Numbers

of students with AS are increasing, year on year, particularly in science based courses. An

initial attempt is made here to map routes into HE, age, gender, ethnicity, and students

chosen academic areas.

This study aims to enable university practitioners, in a range of roles, to work more effectively

with students who have AS. The extent to which people feel adequately prepared, in order to

be able to offer a good service, is investigated. Findings are translated into guidelines for staff

development, and recommendations for good practice, based on a thorough investigation of

interventions which have helped students with AS.

The focus is on the views of a large number of HE staff, with additional information from eight

students and three of their mothers. Active involvement of stakeholders, including primarily

disabled people, in innovations designed to improve their university experience is congruent

with the ethos of the Disability Equality Duty (2006) . Separate introductions written for

students and parents explain the practitioner focus of this study and suggest ways in which it

could be useful to broader audiences or as a catalyst for further research which involves

students who have AS, more directly.

Enhancing staff competence, and confidence in their own ability to assist students with AS

should be a significant ongoing benefit of this research. The purpose of this briefing (and

consultancy and conference presentations arising from the study), is to make a practical

contribution to the development of more effective services. Readers are encouraged to share

the information widely.

8

Objective of the Study

In summary, the overall objective of the study is to evaluate strategies designed to assist

students who have Asperger syndrome (AS) to succeed in UK universities, and to use the

findings as a basis for staff development opportunities and good practice guidelines.

The term ‘practitioners’ encompasses all staff who provide services to learners with AS.

Aims

In order to achieve this objective the following aims have been identified

To critically investigate the literature.

To ascertain whether the number of students with AS appears to be increasing.

To investigate routes into university, and preferred disciplines.

To consider the sort of staff development practitioners require in order to offer better

services.

To understand the nature of the challenges experienced by students with AS.

To evaluate strategies used to assist students with AS in HE.

To recommend pointers for good practice in supporting university students who have

AS.

Hypothesis and Rationale

The rationale behind the formulation of this set of aims is that it is necessary to gain an

understanding from the perspective of the staff who are working with learners with AS (as well

as the students themselves, their parents, and supporters), in order to develop

recommendations for effective practice.

The study is based on the hypothesis that HE students with AS who do not receive

appropriate services are less likely to succeed.

The following sub hypotheses are considered.

The number of students with AS in HE in the UK is increasing.

Students with AS enter HE from non-traditional routes.

There is a concentration of students with AS in science-based courses.

Support available to learners with AS in HE is not consistently effective.

University staff do not feel adequately prepared to work effectively with learners who

have AS.

Background to the Study – Context

Information has been gathered from seventeen UK universities representing a cross section

of institutions.

Data from professionals forms the bulk of the study and has been gained via questionnaires

distributed at university training events for staff working with students with AS , and by email

sent to Disability Officers via the National Association of Disability Practitioner’s (NADP) e

mail list. Participants were asked to reflected on their own experience and development

requirements, via open ended questions.

9

The views of a small number of students with AS, and a smaller number of mothers, have

also been surveyed over time, via structured interviews and questionnaires.

Responses from participants are thematically analysed broadly and in depth. Threads are

drawn together and compared with the very limited quantity of existing structured investigation

in the area. Findings are used to identify effective and less effective strategies. Ideas about

what good practice could look like are developed and presented in a way which is likely to be

of practical use.

Systematic enquiry about routes into university, numbers of students with AS and chosen

disciplines, is patchy. This study aims to begin to address this identified gap.

While university students with AS are currently attracting some attention, few coherent

attempts have thus far been made to synthesise information about their responses to HE. No

systematic enquiry into the reaction of HE staff to learners with AS is currently available and

this study represents the first attempt to scrutinise the issue from this perspective.

The methodology of the study interrogates the hypothesis and sub hypotheses, summarised

in 1.2. The raison d’être of this piece of work is then to turn the resulting findings into practical

guidance designed to benefit students with AS, primarily by enabling university staff to be

better informed and potentially more effective.

10

2. Literature Review

Although literature which considers the impact of AS in the HE context is fairly limited, there is

a growing body of diverse and pertinent information, and opinion about other aspects of the

experience of people with AS. It is necessary to draw upon these sources for background.

Information, for example, from Further Education (FE), has been considered in terms of

possible application at university level.

The literature review is divided into the following sections2.1 Characteristics of AS

2.2 The process of diagnosis

2.3 The effects of AS, with consideration to their potential impact in HE

2.4 Prevalence, gender and changes over time

2.5 Mechanisms for Supporting Students with AS in HE

2.6 Pre HE Experience

2.7 Coping with Change

2.8 Curriculum Versus Support

2.9 Support in HE

2.10 Staff Development

2.11 Critical Review Indicating Gaps in the Literature

2.1 Characteristics of AS and High Functioning / Able Autism (HFA)

Asperger’s syndrome (AS) and ‘high functioning’ or ‘able autism’ are labels attributed to the

university students in this study to evidence their entitlement for Disabled Student Allowance

(DSA). The necessity to prove entitlement to services funded via DSA by providing diagnostic

information from a clinician is a symptom of a system which is heavily influenced by a

‘medical model’ approach (Barnes 1996, 1999, Oliver 1996, Thomas 2004, Shakespeare

2006), the implications of which will be unfolded as a theme. The various routes travelled to

the acquisition of the label are discussed later.

Confusion surrounds the blurred edges between AS, able and high functioning autism (HFA)

and there is no general agreement about how much this matters. The labels are often used

interchangeably ( Attwood 2000, Bogdashina 2006, Boucher 1998,Howlin 2000, Leekham et

al 2000, Ozonoff et al 2000, Schloper et al 1998, Stanford 2003).

People with AS are characterised by at least average intelligence with no significant language

delay up to the age of five (Attwood 2000, 2007,Wing 1992). Some researchers, and a few

people who carry these labels, argue however that there are subtler differences between the

terms. (Blackburn 2000 Bogdashina 2006, Wolff 1995)

The position adopted by Kugler (1998) ,Rutter and Schloper (1992) and others may be

justifiable for the purpose of this study, which aims to present information in such a way that it

can be useful within a defined practical situation.

‘It has been argued that differentiation is needed when the clinical and educational

implications consequent on it are different.’ Rutter and Schloper (1992 :11)

However, given the strength of feeling articulated by some individuals to whom the various

labels of AS and High Functioning Autism (HFA) are attributed, some further discussion is

11

merited. The label may well be critical in respect of an individual's sense of identity (Banton

and Singh 2004, Fletcher 2006, Kelly 2005, Thomas 2004).

Attwood (2000) Nesbitt (2000) and others argue that individuals diagnosed with AS rather

than HFA generally have more ability to use verbal language. Disagreement with this is

perhaps best articulated by Ros Blackburn (2000) who classifies herself as having autism not

AS and an extremely verbally articulate adult (although significant language delay was a

feature of her development in childhood). Blackburn describes herself as needing people to

perform specific functions for her, for example to take her to places where she can enjoy her

all absorbing hobby of trampolining The requirement is for practical help with engaging with

public transport rather than for companionship.

People with AS, in contrast to Blackburn, usually do want and need friends because they

seek to engage in social contact. Loneliness and depression can result from unsuccessful

attempts to join in with intolerant peers. (Attwood 2000, Baron- Cohen in Morton 2001,

Beardon and Edmonds 2007, Bogdashina 2006, Harpur et al 2004, Henault 2006, Tammett

2006) .Individual with HFA or able autism are arguably, possibly, less likely to experience

depression, arising from loneliness, but may feel frustration as a result of not being able to

indulge in activities of choice unless supported by another person (Blackburn 2000).

The Disabled Student Allowance (DSA) system, which is the primary method for accessing

individualised services, requires a diagnostic assessment . Students not comfortable with

being labelled will therefore not access DSA. Those without a clinical diagnosis will not be

entitled to DSA, and adult diagnosis is hard to come by as many of the participants in

Beardon and Edmonds (2007) study have found. The DSA system is not without its critics

(Beardon and Edmonds 2007, Farrah 2006, Fell and Wray 2006,Goode 2007, Lewis and

Corbett 2001, Waterfield et al 2006, Wilson 2005 and others). The main concerns are that it is

cumbersome and should really be redundant in a truly inclusive environment, and assistance

is not always in place from the start of the course, or in contexts such as placement.

Undoubtedly DSA is a medical model gateway, to whatever social model services may follow.

The consequences of not accessing appropriate assistance can be far reaching. (Adams and

Holland 2006, Beardon and Edmonds 2007,Boelte and Poustka 2000, Fletcher, 2006, Meyer

2001, Shakespeare 2006 Stanford 2003). The consequence of being insensitive to a person's

sense of self can equally have far reaching implications. Identity is a complex and personal

construct and disability identity is not something all people with AS, or HFA will attribute to

themselves. In addition, identity is a dynamic state and people will label themselves in

different ways at different points. Bonnie (2004) describes adolescents with AS doing their

best to ‘fit in’ and rejecting the idea of a disability tag. Banton and Singh (2004) , Tregaskis

(2004) and others reflect on the idea of multiple identities. Goffman (1963) articulates the

notion of ‘the spoiled identity'.

Arguably, when a student is disenfranchised from their entitlement to DSA because of their

own discomfort about the attribution of a label such as AS (or disabled), or when support is

not available because of the lack of a gateway clinical diagnosis, challenges arise which are

complex for the individual and the institution. There is not a body of literature which

interrogates this area because, by definition, students who do not see themselves as

disabled or are not comfortable the AS label, or not prepared to acknowledge this at

university, will not come forward to participate in research about AS, and 'undiagnosed'

people may fall outside of relevant systems.

12

In order to provide appropriate services, whether a learner is described as having HFA or AS,

broad background information is arguably useful, as long as it is applied with sensitivity and a

clear understanding that every student is an individual. The following paragraphs provide a

starting point, with apologies for the medical model terminology.

Central to a diagnosis of AS or HFA is the presence of behaviours which characterise the

‘triad of impairments in autism’. Wing and Gould 1989. (in Cumine et al 1998:2.)

Impairment of social interaction.

Impairment of social communication.

Impairment of social imagination, flexible thinking and imaginative play.

Beardon and Edmonds 2007, Hughes 2007 and others point out that 'impairment' is a loaded

word. The literature is full of deficit model language and it is necessary to seek out accounts

written by people who have AS for a more positive picture of strengths and productive

learning differences. (Edmonds and Worton 2005 /2006 Grandin 1996, Hughes 2007 Lawson

2001 and many others).

In 1981Wing (1996) worked from a translation of Asperger’s original paper ‘Autistic

Psychopathies in Childhood’ and provided the first breakdown of the salient features of AS.

Prior to this work Wing and Gould (1979) had carried out a large-scale prevalence study of all

children under fifteen in Camberwell. They found a significant number who exhibited the

features of the triad but less severely than those who would fit Kanner’s description of ‘early

childhood autism’. (Wing 1996). This finding prompted the use of the terms ‘Autistic

continuum’ and ‘Autistic spectrum’

(Cumine et al 1998:3)

The following behaviours are described by Wing (1996) as central to Asperger’s (1944)

observations:

‘Naïve, inappropriate social approaches to others, intense circumscribed interests in particular

subjects such as railway timetables: Good grammar and vocabulary but monotonous speech

used for monologues not two way conversations: Poor motor co-ordination; levels of ability in

the borderline, average or superior range but often with specific learning difficulties in one or

two subjects, and a marked lack of common sense.’

Wing (1996:20)

Ozonoff et al (2000) suggest that people diagnosed with HFA rather than AS often exhibited

more severe language delay in the early years. This was certainly the case for Ros Blackburn

(Blackburn 2000), now a prominent public speaker about autism who’s development

challenges the assumption that individuals with HFA always maintain the minimal verbal

communication exhibited in childhood.

2.2 The Process of Diagnosis

Students in the study all have a diagnosis of AS rather than HFA., therefore, this will be the

focus for the following review. The process of diagnosis is variable. Beardon and Edmonds

(2007), Bishop (1989). Boucher (1998), Jones (2001), Stanford (2003), and Tantam (2000) for

example cite instances of adults with AS being classified as having mental health difficulties.

Howlin and Moore (1997) point to regional variations in average age of diagnosis. Although

13

statistics are not available, the literature contains numerous examples of individuals being

diagnosed in adulthood (Beardon and Edmonds 2007, NAS 1996, Rice 1998, Tantam 2000,

Walker- Sperry 1998). Students in this study describe varied experiences of, and reactions to

diagnosis. Post diagnostic support is often necessary but rarely offered (Beardon and

Edmonds 2007).

Self-identification in adulthood is also increasing as the profile of AS in the media is rising

(Meyer 2001, Slater-Walker 2003, Stanford 2003). ‘Wired’ for example in 2001 published a

checklist of symptoms of AS in an article entitled ‘Take the AQ (Autism Spectrum Quotent)

test’. (Boron Cohen et al’ 2001).

Diagnostic instruments are becoming more widely available for use by a variety of

professionals. Each translates observable features into behavioural indicators, although there

is some discrepancy in detail. The Autism Diagnostic Interview (ADI), a 'semi-structured

interview for parents and caregivers of autistic persons' (Le- Couteur et al 1986) was one of

the first attempts to make the process more accessible to non-professionals. Caution is urged

about the reliability of information yielded from such methodologies, which cannot be

subjected easily to systematic investigation.

Arguably, more widespread use of such instruments and the raised profile of AS in the

popular media may contribute to the apparent increase in identification. Overview of a range

of diagnostic tools and methods are provided by Cumine et al (1998:13-17) Gould (1998:1921) and Wolff (1995:28) Included amongst these is the American Psychiatric Association

(1994) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual fourth revision (DSM IV) Cumine et al (1998)

Lovecky (2004) and others have critically evaluated a range of assessment tools. Because it

is outside the limits of this study to offer a wider critique of diagnostic methodology, a précis of

DSM- IV is provided to give a flavour diagnostic criteria.

DSM-IV

A Qualitative impairment in social interaction, evidenced by at least two of the following:

1. Marked impairment in non-verbal communication, including eye contact, facial expression,

body postures and gestures to regulate social interaction.

2. Peer relationships not appropriate to developmental level.

3. Lack of spontaneous sharing of enjoyment, interests or achievements with others.

4. Deficit in social or emotional reciprocity.

B Restricted, repetitive, stereotyped behaviour, interests or activities, indicated by at least

one of the following.

1. Abnormally intense or focussed preoccupation with stereotyped pattern(s) of interest.

2. Rigid adherence to non-functional rituals or routines.

3. Stereotypical and repetitive gross or fine body movements.

4. Persistent preoccupation with parts of objects.

C Symptoms described in A and B occurs to an extent which impairs functioning.

D. Early language delay not noted.

E. Lack of other significant developmental delays.

F. Criteria for schizophrenia or other specific pervasive developmental disorders ruled out.

Ambiguous Diagnosis

Because DNA evidence of an exact diagnosis of AS is not available, there is the possibility of

ambiguous application of observational criteria, leading to erroneous ‘diagnosis’.Literature is

scant but includes examples of people with Specific Learning Disabilities apparently

14

manifesting signs of AS. (Newson 1998), and movement between labels, including ADD and

ADHD (Stanford 2003).

Stanford (2003:34) asserts that ‘A diagnosis can be a matter of opinion making it difficult to

quantify’. Practitioners are cautioned to reflective on the power of labelling and not to label

individuals who may just appear ‘eccentric’. The role of HE practitioners in diagnosis is clear.

The vast majority are not qualified to make such a judgement.

Schloper et al (1998; 394-395) express concerns, shared in this study, that

‘the premature use of the AS label… serves as a seriously flawed model… It frequently

appears that advantages (of diagnosis) from a professional perspective were disadvantages

from the parent/ client perspective’.

Boushey (2007) and Hodge (2005) cite parents who described fear for the future when their

children received a diagnosis. Parental expectations can be adversely affected, and this can,

in turn, limit the child's later opportunities (Madriaga 2006). Changes as the child matures

into adulthood may be significant and parental expectations can be exceeded. An individual

who exhibited characteristics of AS to a marked extent at the age of ten for example, may

manifest a far more mature personality in their twenties, while retaining features of the

condition which are no longer as close to the surface. Research is lacking in this area

(Pellicano 2007).

In an inclusive environment, arguably, services should be flexibly available to meet individual

requirements, without the necessity to apply a disability label which may have a negative

impact in itself. (Hall and Stahl 2006).Unfortunately, access to support from the DSA is still

dependant on a medical model approach requiring a label in order to access a service.

Participants in the study described students without a diagnosis who seemed to exhibit

characteristics of AS. Practitioners knew of others who had been diagnosed with AS but

chose not to access support services badged as being for disabled students because they did

not view AS as a disability.

Others may have felt stigmatised. Alvarez and Reid (2003:289) cite examples of individuals,

who have encountered negative reactions from others when a disclosure of autism is made

and advise that the goal of disclosure should be,

‘To effect a change in the relationship with another person or persons to bring about a better

sense of mutual understanding and trust’

Alvarez and Reid 2003:290

Good practice advice arising from this study is mindful of the position described by Alvarez

and Reid (2003) and the rights of the student under the Data Protection Act (1998) and DDA4

(2002)

Although ambiguous diagnosis ,not acknowledging AS at all, or not viewing it as a disability

are of interest, essentially, they have to remain outside the scope of the study. A separate

investigation of the long term development of people diagnosed with AS in childhood would

be useful. Information from students (and their parents perhaps) about their development may

provide evidence for the view that some have exceeded parental expectations. Students who

had a childhood diagnosis of AS and do want or do not require assistance, are also not

represented.

15

The Purpose of Diagnosis

Volkmar (1998) described the function of any diagnostic system:

‘The intent of system like DSM-IV and ICD-10 is to help clinicians and investigators to do a

better job defining autism. They do this by alerting the evaluator to the fundamental features

of the diagnostic concept without (hopefully) making the evaluator blind to the overarching

goals of the diagnostic process. It is the latter process in which the individual is seen in the

totality of her / his environment and needs, that form the basis for programme planning.’

Volkmar (1998:55)

Volkmar’s position fails to acknowledge the potential negative impact of labelling. The role of

diagnosis as a means of accessing resources is critical to this study.

Specific Learning Difficulties

In addition to the criteria emphasised in DSM-IV, other features have been associated with

AS which may well have an impact on the university experience.

Indicators of Specific Learning Difficulty (SpLD), quoted by Wing (1981) from Asperger’s

original 1944 paper (in Wing 1998) have obvious relevance to teaching and learning. As with

dyspraxia for example, organisation and attentional difficulties and motor clumsiness can be

present (Jordan 1998). A recent Department of Education and Science (DfES 2005) working

party focussing on SpLD in HE, discussed at length whether to include AS within an SpLD

framework. The definition included attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and

dyspraxia. After much debate, the position was adopted that the extent of overlap is unknown

and those with AS can exhibit a range of characteristics beyond the SpLD definition adopted.

Sensory Issues, Executive Function and Central Coherence

Attwood (2007) Beaumont and Newcombe (2007) Bogdashina( 2005) Happe et al (2006)

Ozonoff (1995) Phillips et al (1998) and others have identified deficient executive functioning

which can create problems with planning, organisation and problem solving, and issues with

central coherence, governing the ability to focus on relevant information, rather than getting

bogged down in detail, as characteristics of AS. Organisational challenges are often faced by

other students with SpLD’s so borrowing advice from, for example, study skills sessions

designed for students who have Dyslexia could be of some benefit.

Atfield and Morgan (2007) Bogdashina (2006) Clements( 2005) Grandin and Johnsone (2005)

Lovecky( 2004) Tammett (2006) and others describe differences in attention and the

processing of sensory information leading to distractibility, stress and discomfort. Beardon

and Edmonds (2007) cite numerous examples of students struggling with the sensory

environment.

Selectively attending only to situations perceived as relevant to a particular interest could

impact negatively on learning. Difficulty with assimilating information into a coherent whole

picture, described by Frith (1989) as ‘weak central coherence theory’. can lead to problems

around generalising learning across contexts. Participants in Beardon and Edmond's (2007)

highlighted this area.

16

Health and Wellbeing

Intermittent mental health difficulties, including anxiety and clinical depression (Attwood 2007,

Hare 2004) are also described. Clearly episodes of mental ill health will impact on

performance at university.

Health concerns, such as food intolerances, with their obvious implications when trying to

adapt to a new home and a different diet, are cited by Waring and Ngong (2005) and others.

Ringmn and Jankovic (2000) and Canitano and Vivanti (2007) have observed motor tics

reminiscent of Tourette’s syndrome in individuals with a diagnosis of AS. Puberty onset

epilepsy (Attwood 2000, Jones 2001) has been documented. The presence of behaviours

associated with Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD), anorexia and depression have been

observed by Berjerot (2007). It is possible of course to have more than one impairment. It is

also possible for characteristics of AS to be diagnosed as something else. A student

intensely anxious about money may not be eating because he is reluctant to buy food, or he

cannot stand the sensory environment of the refectory, not because of anorexia. OCD like

behaviours may be indicators of intense interest or manifestations of an anxiety reaction. It is

important to understanding what is behind behaviour rather than intervening on the basis of

an assumption.

2.3 Potential implications of the interaction between features of AS and characteristics

of universities

Isolation

Difficulty with social interaction, social inexperience, and the desire not to repeat previous

negative experiences with peers, including bullying (Breakey 2006, Henault 2006, Mitchell et

al 2007, Hughes 2007, Tammett, 2006) may lead to social isolation. Student with AS may be

very keen to make friends and may well experience rejection, which may lead to depression

and low self-esteem. (Attwood 1993, 1998, 2000, Clements 2005, Edmonds and Worton

2005, 2006 Hare 1997, 2004, Jones 2001, Kugler 1998 Molloy and Vasil 2004 NAS 1996).

Someone who is unhappy about their AS label may experience further inhibition about trying

to make friends.

Evidence is cited by Curtis, in Donnelan (2004) that feelings of isolation are however, not

limited to students with AS. Sophie Allchin (in Donnelan , 2004), a phone help line coordinator from a London university cited many instances of students expressing concerns

about social seclusion, uncertain about how to cope financially and feeling of being the only

one who has not succeeded in making friends.

Low Self Esteem

Depression and low self esteem may arise from social isolation, loneliness, and feeling like

the odd one out. For a student with a diagnosis of AS which they reject, identity issues may

impact on self esteem. Beardon and Edmond’s (2007) provide numerous examples of people

depressed and frustrated by not being able to access a clinical diagnosis.

Media portrayals are unhelpful, with their use of stereotypical terms (Broach 2002, Crewe

2002, Cohen 2007,Haddon 2003), describing people said to have AS as both brilliant and

socially inept (like Einstein), or in some ways tragic. Macnair (2007) on a BBC helpline for

example uses almost exclusively negative language to describe AS (insensitive, unaware,

and obsessive) conceding only that an affected person ‘may be good at learning facts and

17

figures’. In contrast with Macnair, Pollak (2007) on the BRAIN HE website unusually, cites

positive characteristics and uses the term ‘neurodiversity’ which emphasises potentially useful

differences in learning styles, rather than seemingly insurmountable oddities and difficulties.

Some people who have AS and communicate with each other via the internet, like the term

neurodiverse. (Aspergerunited.org, Aspiesforfreedom.com and others).

Narrow Range of Interests

Having a very narrow range of interests may have a negative impact on motivation to spend

time on other aspects of the course outside the specific area of fascination. (Mercier et al

2000.NAS 1996.). Alternatively, the ability to focus, apply oneself and work hard could be

described as very desirable attributes.

A minority (Baron –Cohen and Bolton 1993 suggest around one in twenty) develop restricted

special abilities born of exclusive concentration on a narrow field. (Baron-Cohen in Morton

2001,Grandin and Scariano 1986, Sacks 1995, Pring et al 1997) These can lead to high

levels of achievement.. Mercier et al (2000) and Moyes (2002) caution against viewing

restricted interests as wholly negative.

'Restricted interests provide a sense of well being and positive ways of occupying ones time,

a source of personal validation and an incentive for personal growth'. Mercier et al (2000:406)

Frith 1999, Harpur et al 2004 and others provide examples of historical figures apparently

displaying characteristics reminiscent of AS. These include Einstein, Mozart, Newton and Van

Gough. (Without mentioning ‘the A (autism) word’, Bill Bryson (2003) offers credible

descriptors in vignettes about the personalities of Cavendish, Newton and others). Wikopedia

(a popular source, frequently accessed) also yields a rich crop of names, including those cited

here plus –Gary Numan (singer songwriter), Sotashi Tajiri (games designer) and, richest of

all, Bill Gates (of Microsoft fame).The extent to which evidence from (predominantly male)

mainly historical figures can be deemed to be reliable is limited. Einstein is also described in

other context as having dyslexia, and Mozart, Tourette’s syndrome, which possibly illustrates

the point that retrospective evaluations have limited validity.

Personal accounts by people with AS, including Temple Grandin (Grandin and Johnson

2005), and Daniel Tammett (2006) are more convincing, and argue that characteristics

associated with autism, particularly application, have played a major part in their success.

Time and focus are critical to high levels of achievement, and the development of ‘genius’

(Dobbs 2006). Making a virtue of the ability to ‘single task’ and harnessing the desire to work

exceptionally hard feels like a more positive way of describing 'application' rather than using

the term ‘obsessive behaviour’.

Negative Emotions

Anxiety and depression are well documented (Attwood 2007, Beardon and Edmonds 2007).

Perfectionism can lead to negative feelings about not being good enough. The study yielded

examples of students who had A level papers remarked because they were unable to accept

any grade below A. Beardon and Edmonds (2007) produced numerous stories of people with

AS experiencing massive levels of frustration around trying to cope with day to day life without

adequate services.

A body of knowledge is being amassed by and about people who are able to acknowledge

their AS, (Edmonds and Worton 2005. 2006, Harpur et al 2004. Jackson 2004, Lawson 2006.

18

Shore 2006 Tammett 2006, Webster 2005). In addition, the internet is beginning to provide a

huge quantity of information produced by people with AS. Those who are not able to talk

about their feelings about having a diagnosis of AS are inevitably disenfranchised. A key

ethical consideration of this study is not to induce distress therefore approaches to learners

suspected of having AS by professionals were completely off limits, so advice to staff relating

to this remains hypothetical.

Concerns about Changes in Routine

There is much evidence to suggest that anxiety reactions are often prompted by even

apparently minor changes in routine. (Blackburn 2000, Breakey 2006, Debbault 2002,

Grooden et al 1994, Harpur et al 2004, Lawson 2006, Mesibov et al 1994. Martin 2000,

Tammett 2006, Smith 2003). It is possible, though certainly not inevitable, therefore that a

major life change, like starting university, particularly if this also involves moving house, may

cause traumatic reactions which could manifest dramatically in environments outside the

classroom, such as residential accommodation. (Clements, 2005, Howlin 1997) Staff

responsible for student housing could be called on to deal with the consequences of for

example the reaction of flatmates to behaviour around routines and rituals. The thorny issue

of involvement of peers could then arise. (Martin (2007) Logically residential services staff

and others need to have a level of positive awareness in order to develop appropriate

services.

Theory of Mind

Frith (1989 and 1991), Baron Cohen, in Morton (2001), Howlin et al (2000) and others

describe impairments in the ability to develop a ‘theory of mind’, resulting in an inability to

empathise with others and an insensitivity to their feelings. (Attwood 2001, Tantam 1992,

Howlin et al 2000).The following example cited by Howlin et al (2000) demonstrates a

potential impact of an ‘inability to take into account what other people know’.

‘Jeffrey, an extremely able young man with autism who held a responsible position in a

computing company, was unable to appreciate that if he had witnessed an event, this

knowledge might not be shared by others. He was unable to comprehend his experience was

different from theirs, often referring to events without providing the essential background

information necessary for colleagues to understand the context of his argument’

Howlin et al (2000:9)

Group work requires the ability to collaborate, preferably without irritating other participants.

Geoffrey's challenges with theory of mind may make this hard.

Without a maturely developed ‘theory of mind’ it may not be possible for an individual to be

clear about other people’s intentions. This could increase vulnerability, for example to forms

of bullying or exploitation. (Beardon and Edmonds 2007,Celani 2002. Debbault 2002. Howlin

1997 NAS 1996, Roberts 1995).

Alternatively lack of theory of mind can result in being insensitive to the feelings of other

people. This may result, for example, in the student with AS not being the ideal flatmate –

possibly an area of research interest, although, ethical considerations may well constrain this

avenue of investigation. Goleman (1999) popularised the term ‘emotional intelligence’, and

would describe lack of sensitivity as an example of a deficit in this area.

19

Studies cited can be criticised for not taking a longitudinal perspective on the potential

development of a greater degree of empathy over time and with increased life experiencethis may also be a useful area for further exploration. Thompson (2004) evidenced some

success improvements in apparently empathic reactions within the context of a small scale

action research project focussing on couple counselling. Wood and Tolley (2003) suggest

that it is possible for individuals to boost their own emotional intelligence (EQ), although this

view is not supported by Humphrey et al (2007) and the participants did not have AS. Shore

(2006) reflects on a personal progression towards a more empathic state.

‘The only difference between my having empathy, and a person not on the autistic spectrum,

is that I have to access it cognitively where as most people empathise automatically’

Shore 2006:202

Bogdashina (2006:13) echos the view that ‘autistic individuals have to learn many aspects of

neurotypical people theoretically’. NT people , who notionally do not have difficulty with

theory of mind,, should perhaps think about making use of their highly developed empathy

mechanisms in order to try and see the world from the perspective of people with AS.

Communication

Presenting language skills, although superficially adequate may mask comprehension

deficits. (Hawkins 2004, Lawson 2006) which can be due in part to uncertain theory of mind

(Baron –Cohen and Bolton 1993, Howlin et al 2000). Researchers need to be mindful of this

when considering the ethics of participation by people with AS, and make strenuous efforts to

ensure that understanding by participants makes informed consent is a reality.

A tendency to interpret language literally can lead to social and academic confusion.

(Bogdashina 2006, Frith 1989, Newson 2000) Not fully absorbing the subtleties of social

situations may include uncertainty between action and intention, an insecure sense of danger

and sexual vulnerability (Beardon and Edmonds 2007, Fitzgerald et al 1998, Williams 1992).

Words to describe feelings may not come easily (Baron-Cohen in Morton 2001, Celani 2002,

Peeters 1997, Thompson 2004). Arguably this may extend to difficulty in recognising physical

feelings such as hunger, thirst or tiredness. There is not a body of evidence to support this,

although high threshold of tolerance for physical pain is described (Attwood 2002), perhaps

erroneously. Blackburn (2000) discusses not wanting to acknowledge pain because of the

adverse reaction she experienced from being comforted.

While ‘communication difficulties’ are discussed frequently, a body of systematic

implementation and evaluation of strategies which may enhance communication skills of

adults with AS over time is lacking in the literature. (Thompson 2004). Concentration on

problems without due consideration of potential ways to ameliorate them could be described

as a ‘deficit model approach’. The aim of this study is to move beyond this towards practical

strategies which may be helpful learners with AS. Communication is a two way street so

locating difficulties with one partner in an interaction is unfair.

Self Harm

Self-injurious behaviour has been observed. (Arnold 2004, Curtis 2004, Hare 2004, Jordan

1998) Theories about why this is so include self harm as a manifestation of low self esteem

(Attwood 1998) or an attempt to control the environment by focussing sensory stimuli into a

tangible form, such as controllable pain from gouging the skin, (Blackburn 2001)

20

Research in this area would need to be mindful about the extent to which self harm is

common amongst university students without AS. O’Connor (2005) stated that 1% of the

‘general’ population self harm. Meikle (2004:29) cite self reported evidence (from a sample of

6000) that one in ten, fifteen and sixteen year olds indulge in behaviours such as cutting and

overdosing. The incidents has not been investigated as extensively in the HE population and

caution is required about over generalising results from a survey based on younger

teenagers.

An increase in publicity around self harm, argues Arnold (2004), may in some cases

precipitate the behaviour. This study yielded one report about a student with AS who said

that she had cut herself because she believed that this was a way to get to see the college

counsellor. In this instance the action was apparently the result of a misunderstanding.

Reactions to Sensory Stimulation

Examples are common of an unfriendly sensory environment, for example in a bright and

noisy classroom, precipitating anxiety responses. (Attwood 2000, Bogdashina 2003,

Clements, 2005, Grandin 1996, Irlene 1997,Sicile-Kira 2003, Vermeulen 2001,Williams 1992

.2004.). Sensory overload was cited as a stressor by participants in Beardon and Edmonds

(2007) survey.

The Family Context

An NAS (1996) survey cited numerous examples of stresses experienced by the person with

AS manifesting themselves in behaviour within the family setting. Sleep disturbances,

hyperactivity, and behaviour which embarrassed family members were described. Reactions

played out at home may not necessarily be apparent at university. (Baron- Cohen and Bolton

1993, Ashton Smith 1997, Jordan 1998) Martin 2000, Williams et al 2004). The area of

communication between parents and university is thorny.

Students are advised by Harpur et al (2004) to be proactive in making use of the backup

family members can provide. This advice may signal an empowering ethos by which learners

are enabled to take some control. Adult students may not want contact between university

and family and finding ways to respect this perspective can be challenging.

DSA assessors involved in this study described problems when interviewing students for

DSA, because parents tended to assume that they should be present and answer the

questions.

Changes over Time

There are few exceptions (Rimland 1994) to the view that autism is incurable, although

individuals diagnosed in childhood may go on to exceed expectations (Blackburn 2000, Lipp

2006, Peers 2003, Tammett 2006). The idea of ‘a cure’ is also highly charged. (Barnes 1999,

Beardon 2007, Bogdashina 2006, Oliver 1996, Pollak 2005, Shakespeare 2006) . The

assumption that the difference, culture, neurodiversity, of autism is something to be

eradicated begins to smack of eugenics.

Examples of tangible behavioural change over time are noted in case studies and

autobiographies. Alvarez and Reid (2003) describe self stimulatory behaviours diminishing in

young adults previously exhibiting these obviously autistic characteristics. Blackburn (2000),

Grandin (2003), Tammett (2006) and others have become highly successful while retaining

characteristics associated with autism and AS.

21

Thompson (2004) analyses factors which have improved communication between couples

where one person had AS. Cognitive Behavioural Therapy as a strategy to address

‘psychological problems’ has been used with some success by Hare (2004).

In each example, research samples are small and longitudinal impacts of interventions are

not interrogated fully. In depth evaluation of factors possibly influencing behavioural change

is lacking so it is not possible to conclude whether intrinsic or extrinsic influences are most

relevant.

Where behaviours occur in response to anxiety and confusion, there is evidence to suggest

that positive environmental modification leading to more predictable routines, can precipitate

desirable behavioural change, in response to a feeling of greater security. Maclean-Ward

(2003) Peeters and Gilbert (1999) Slater-Walker (2003) and Smith (2003), cite examples from

employment and education, of apparently greater relaxation as routines became clearer.

Slater-Walker (2003) an individual with AS, cautions however, that worries persist below the

surface. Professionals are reminded not to assume that the person with AS has simply ‘got

over it’, and to be aware that anxieties can resurface.

Boelte and Poustka (2000) suggest that some adults and adolescents can be excluded from

their original childhood diagnosis because of improvements in their presenting characteristics,

particularly as a result of diminishing repetitive behaviour. Systematic investigation into

strategies used by the individual with AS to present themselves in a certain way, or their

motivation to do so, are not available. The amount of effort a student with AS is employing in

an attempt to fit in could be enormous (Harpur et al 2004).

It is possible that a university student diagnosed as having AS in childhood has lost this

diagnosis during adolescents despite retaining certain behaviours congruent with an AS

profile, some of which will remain beneath the surface for much of the time. The minority of

individuals originally diagnosed with AS or HFA who go on to describe their own

achievements still report that they retain autistic characteristics, particularly around anxiety

prompted by change and unfamiliar situations. ( Aston, 2001, Blackburn 00, Deimel 2004,

Fleisher ,2003, Grandin and Scarino 1986, Holliday-Willey 2003, Sicile-Kira 2003,SlaterWalker 2003, Tammett 2006, Vermeulem 2001,Williams 1992 and 2004,. Windibank 2002)

Students possibly trying to get away from what they may perceive as an autistic past, or

erroneous early diagnosis, have not been targeted for this study for ethical reasons. The

perceptions of individuals with this sort of history however would provide greater balance to

discussion.

Disclosure

The extent to which it would be beneficial for peers, including flatmates, of students with AS,

to have some understanding of the condition, merits further discussion. (Alvarez and Reid

2003, Equality Challenge Unit 2004, Martin 2006, Stanford 2003). Issues of confidentiality and

the right of the individual to choose how and to whom they disclose information about their

disability, is relevant here. Leach and Birnie (2006:75) make a suggestion which is difficult to

understand, and begs the question ‘why should s/he?’

‘If the student (with AS) has idiosyncratic behaviour traits, e.g. grimacing, ask for their

permission to explain to the rest of the group’

22

Perhaps a general discussion with the rest of the group about valuing diversity would have

more merit?

Disabled people have a legal right to keep control of personal information which can not be

shared without their informed consent. (Equality Challenge Unit 2004:47).

2.4 Prevalence, Gender Distribution and Continuation into Adult Life

A National Autistic Society (NAS) survey of the views of 267 adults and their carers

conducted in 1996 emphasised the relative recency of recognition.

‘We are now living with the first generation of people who have an official diagnosis of autism

or Asperger’s syndrome, the oldest being approximately in their late forties’

NAS (1996:2)

Despite difficulties associated with diagnosis, information about prevalence and gender

distribution is available. In 1993:1327 Ether’s and Gillberg published a total population study

of all school-aged children in Goteborg, a sample size of 1401. They concluded that there

was a ‘minimum prevalence of 3.6 per 1000 with a male to female ratio of 4.1. p1327. When

people described as ‘borderline’ were included, the number rose to 7.1 per thousand. Baron

Cohen in Morton (2001) suggests that the figures are much higher, possibly one in two

hundred UK school aged children. (Debbaudt 2002) quotes one in two hundred and fifty in the

USA) Recent prevalence studies clearly do not illuminate the progression of children into

adult life, and do not necessarily articulate the severity of the condition in individuals.

There is some limited evidence, of debatable quality, of clustering in specific geographical

areas. A notable example being Silicone Valley in the USA. Fathers within the ICT field are

the common denominator, allegedly producing a disproportionably high number of children

with autism (Silberman 2001). The findings are included cautiously as little detail of research

design was given, and no follow up study of the Silicone Valley children is available to

ascertain the extent or persistence of autistic features over time.

This study does suggest a concentration of students with AS in science based courses.

The NAS (1996) survey suggested that, at the time of publication, there were around 322500

individuals with autism in the UK. AS was found at that time (NAS1996) to affect between

twenty and thirty people in every ten thousand with nine times more males than females

diagnosed. Kanner’s classic autism was found in four to five people in every ten thousand

with a ratio of four males to one female. As the condition is becoming better known, via the

media as well as between professionals, the numbers identified are beginning to expand.

(Cann 1997, 1998) Since 1996, the increase in diagnosis appears to be startling. (Tantam

2000).

Of particular relevance to this study is Tantam's (2000:61) suggestion that'The recognition of a much larger group of people with AS but with sufficiently good social

functioning to have missed diagnosis previously has also changed our understanding of what

people with AS can achieve'

23

Tantam’s (2002) observation is congruent with the comments of university staff participating

in this study. Each cited examples of students who behaved very like those with AS, but were

undiagnosed. Also a small number were described as being adamant that, despite being

labelled as having AS that they were not prepared to acknowledge this as a disability. This

contributes to the assertion that prevalence information is unlikely to be accurate.

The discrepancy between the prevalence figures quoted can be accounted for, in part also, by

the use of different diagnostic methods. This in itself highlights some of the difficulties

associated with precise diagnosis.

For the purpose of this study the important finding is that AS is common enough for university

staff to expect to come across affected students, particularly in the current climate which

advocates widening participation, of non-traditional learners (Kennedy 1997), lifelong

learning, (Watson and Taylor 1998) and more appropriate support for students with

disabilities, (DDA4 2002 DFES 2004-5, QAA 1999).

Stanford (2003:34) cautions that‘The number of adults recognising their need for as AS diagnosis is growing daily and reveals

a harrowing need for research towards solutions for adults who have received no intervention

or support over the decades’.

Longitudinal Studies

Very few studies have followed people with autism into their adult life (Newson et al 1982,

Attwood 1993, Baron Cohen and Bolton 1993, Walker- Sperry 1995, Wing 1998). Qualitative

changes in behaviour over time have been noted in longitudinal research (Boelte and Poustka

2000). Wing (1998) describes instances where progress has resulted in a shift in diagnosis

from autism to AS.

During this study, anecdotal evidence of students whose history indicates significant autistic

characteristics in their earlier childhood has come to light. This points, possibly, to a potential

avenue of further investigation.

Adolescence is considered by Baron- Cohen (1993) to be a period which can be associated

with deterioration of functioning, with possible onset of epilepsy. (Attwood 1993, Carlton

1993) The early twenties, however Attwood (1993) suggests from his clinical experience, can

be a time of significant progress. Cautious support is given to Attwood’s observations by

Baron Cohen (1993). He has noticed progress in social interactions around the late twenties

including increased interest in people, showing and receiving affection and greater tolerance

of change, provided that appropriate opportunities are made available. Lawson (2001 /2006)

suggests that, over time, people with AS can learn social as well as other skills via the

intellect rather than instinctively. Assistance to develop understanding for example of why

neurotypical people do the strange things they do and how best to respond is something that

Beardon and Edmonds (2007) participants would have welcomed.

Baron Cohen’s (2001) assertion, in Morton (2001)that AS is on the increase, based on a

study of upper primary aged children, may merit further longitudinal investigation given his

observations of progress over time. A twelve year old child, for example, may be very

disabled by AS but may mature into a university student able to cope better than was

originally anticipated.

24

Numbers of Students with AS in HE

Since 2003-04, HESA data has been collected about students who declared them selves to

have an ‘Autistic Spectrum Disorder’ (ASD). The increase over the last three years is startling.

In 2003-04 sixty first year undergraduates declared, by 2004-05, the figure had risen to two

hundred. By 2005-06 three hundred and twenty first year undergraduates disclosed ASD. The

number of higher degree students rose from none in the first year the data was collected, to

twenty in 2004-05, and forty five in 2005-06. Around three quarters of each cohort was male.

Prior to 2003-04 ASD was not available as a separate field. Statistical information is available

from HESA (1994-2005) about the numbers of students with disabilities, classified by

impairment, and accessing Disabled Student Allowance. An increase in those declaring ‘other

disabilities’ from 1735 in 1994 to 5575 in 2003 possibly captured the some of the cohort of

students with AS. Alternatively, HESA and The National Disability Team (NDT) 2005, report

that .065% of the total student population identified as having ‘An unseen disability’ which is

another HESA field which people with AS may have marked, (an increase of lesser

proportions, from 7615 in 1994, to 8775 in 2003 was noted in this category).

Those unwilling to disclose will not choose to tick any of the categories. Because of a

tendency to interpret language literally, it is also feasible that a person with AS would have

avoided marking a box when there was not one available which described their condition as

AS. Data about students with AS who do not access DSA is inevitably limited and unreliable.

Progression Beyond University

Statistics are gathered at various points during a learner's university career, and immediately

post exit. It is possible that people with AS could be identified by this system to an extent, but

again, inconsistently. Croucher (2004), for example, identified destinations of 2002 disabled

graduates, but again, AS was not a discreet category in this research so the findings are of

limited value to this study. Further limitations, identified by Croucher, include the lack of

longitudinal follow up. HE was certainly identified by Croucher (2002;2) as ‘one significant

factor in the success of disabled people in the labour market’ which is unsurprising. BaronCohen (2003) suggests that people with AS are often more successful in occupations

requiring a scientific systemising aptitude rather than highly developed empathy skills. The

extent to which people with AS are under employed, in relation to qualifications, or

unemployed, has not been rigorously investigated but Beardon and Edmonds (2007) cited

numerous examples.A longitudinal study of career progression of graduates with AS would be

a valid project, as a gap in the literature is evident here.

2.5 Mechanisms for Supporting Students with AS in HE

Relevant Legislation and its Influence on Practice

Widening participation and lifelong learning are strategic responses to education legislation

designed to facilitate greater social inclusion in post compulsory schooling. (Action on Access

2005, Ball 1990, Dearing 1997, DfEE 1998, Fryer 1997, Kennedy 1997. NDT 2005. O’Neill

2005). Learners from financially disadvantaged backgrounds, and people who were the first in

their family to go to university, and those who accessed higher education via routes other

than the traditional three A Levels, received a great deal of media attention, and disabled

students tended to be less high profile, in the early days of widening participation. (Dickinson

2005, Wray and Houghton 2007) Consequently, it was difficult, particularly prior to 1994, to

ascertain how many disabled students were going on to university, and the steps they had

taken to get there. HESA (2003) statistics from 1994 onwards describe a steady increase in

25

the numbers of disabled students in HE, based on take-up of the Disabled Student Allowance

(DSA). The information is not a complete picture, as not all disabled students make use of

DSA. There is not a reliable means of discerning across the country whether non- traditional

routes into university are favoured over A levels by students with AS. This study begins a

small-scale interrogation of this, (as well as the age, gender and subject areas).

Tomlinson (1996) signalled a move to facilitating genuine inclusion by advocating a more

flexible, learner centred approach in order to cater increasingly effectively for non traditional

learners, originally in further education and later in HE. The intended focus of Tomlinson was

broader than disability but the report is associated closely with signalling an improvement in

provision for disabled learners and the publication was influential in encouraging practitioners

to think about their pedagogy, and the reduction of potential barriers for students. People with

AS are providing information about their favoured individual learner style which could usefully

inform practitioners. Arnold (2003), Lawson (2006), Grandin (1996) and others provide

examples including single attention, a systematic approach focussing on one thing at a time,

and employing visual strategies. Asperger (1944) was the first to suggest that teaching was

likely to be more use with the affect turned off and the logical systematic approach turned on.

A set of guidelines issued by the Quality Assurance Agency (1999) alerted practitioners to

their responsibilities under the then forthcoming DDA4 (2002). The Disability Equality Duty

(2006) further emphasises statutory requirements to proactively promote and develop a

sound inclusive learning culture. Helping practitioners to gain an understanding of what

inclusion means, and to embrace the underpinning values and benefits to all students, in

practice, is probably more helpful than putting the frighteners on about legal obligations.

By December 2006, all public bodies, including universities, were required to produce a

Disability Equality Scheme (DES) which set out, in a three year action plan, how

responsibilities under the Disability Equality Duty (DED) would be addressed. Proactive

promotion of disability equality at the highest level, and a cultural of active involvement of

disabled people in institutional development were envisaged as an outcome of the DED over

time. Listening to students who have AS is entirely possible within the context of good

practice in disability equality training. Madriaga et al (2008) have started to provide a platform

for students with AS to talk to practitioners and the evaluations have been extremely positive.

In theory then, by 2010 consideration of the requirements of disabled people will be on the

agenda as an ordinary accepted part of institutional planning, and disabled people

themselves will be highly visible in the process.

The phenomenology of the author, as a University Disability Advisor, and Vice Chair of The

National Association of Disability Practitioners (NADP) at the time of writing, could create the

false perception that services for disabled students in HE are now excellent because of the

requirements placed upon universities to improve provision. Mixing with like-minded

colleagues with a sense of ownership of the agenda, and a deep sense of conviction about

the human rights of disabled people, makes it easy to own the remit of the DDA the DED,

and The Human Rights Act (1998) which includes ‘a right not to be denied education’. Staff in

other roles may well have less expertise, different priorities and different passions. Despite

QAA (1999), DDA4 and the DED emphasising the shared responsibility of the institution,

anecdotal evidence would suggest that there is still a sense of locating ‘disability issues with

the disability officer’. In reality, disability officers and those with similar roles are likely to have

far more understanding of the agenda than do other staff in the institution. The author is

26

mindful in this study that participants have self selected because of a desire to know more

about working with students with AS. Their view should not therefore be taken as

representative of the whole institution which may well contain other staff with little interest.

Increasingly, however, strategic planners are required, as a result of legislation, to develop

inclusive practice (Adams and Brown, 2006, Adams and Holland 2006, Hall and Stahl 2006,