Derivation of the Ordinary Least Squares Estimator

advertisement

1

Derivation of the Ordinary Least Squares Estimator

Simple Linear Regression Case

As briefly discussed in the previous reading assignment, the most commonly used

estimation procedure is the minimization of the sum of squared deviations. This procedure is

known as the ordinary least squares (OLS) estimator. In this chapter, this estimator is derived for

the simple linear case. The simple linear case means only one x variable is associated with each

y value.

Simple Linear Regression

Error Defined

The simple linear regression problem is given by the following equation

(1)

y i a bx i u i

i 1, 2, , n

where yi and xi represent paired observations, a and b are unknown parameters, ui is the error

term associated with observation i, and n is the total number of observations. The terms

deviation, residual, and error term are often used interchangeably in econometric analysis. More

correct usage, however, is to use error term to represent an unknown value, residual, deviation,

or estimated error term to represent a calculated value for the error term. The term “a” represents

the intercept of the line and “b” represents the slope of the line. One key assumption is the

equation is linear. Here, the equation is linear in y and x, but the equation is also linear in a and

b. Linear simply means nonlinear terms such as squared or logarithmic values for x, y, a, and b

are not included in the equation. The linear in x and y assumption will be relaxed later, but the

equation must remain linear in a and b. Experience suggests this linear requirement is an

obstacle for students’ understanding of ordinary least squares (see linear equation review box).

You have three paired data (x, y) points (3, 40), (1, 5), and (2, 10). Using this data, you

wish to obtain an equation of the following form

(2)

y i a bx i u i

where i denotes the observation, a and b are unknown parameters to be estimated, xi is the

independent variable, yi is the dependent variable, and ui is the error term associated with

observation i.

Simple linear regression uses the ordinary least squares procedure. As briefly discussed

n

in the previous chapter, the objective is to minimize the sum of the squared residual,

û

t 1

2

i

. The

idea of residuals is developed in the previous chapter; however, a brief review of this concept is

presented here. Residuals are how far the estimated y (using the estimated y-intercept and slope

parameters) for a given x is from an observed y associated with the given x. By this definition,

residuals are the estimated error between the observed y value and the estimated y value.

2

Included in this error term is everything affecting y, but not included in the equation. In the

simple linear regression case, only x is included in the equation, the error term includes all other

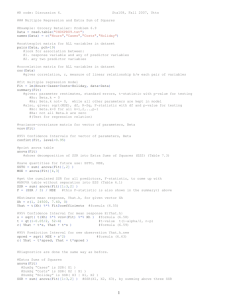

variables affecting y. Graphically, residuals are the vertical distance (x is given or held constant)

from the observed y and the estimated equation. Residuals are shown graphically in figure 1 (as

before figures are at the end of this reading assignment). In this figure, residuals one and two are

positive, whereas, residual three is negative. For residual one, the observed y value is 40, but the

estimated y value given by the equation is 35.83. The residual associated with this data point is

4.17. Recall, residuals are calculated by subtracting the estimated value from the observed value

(40 - 35.83). In general terms, residuals are given by the equation û i y i ŷ i where the hat

symbol denotes an estimated y value (the value given by the equation). Note the subscript on û i ,

as before this subscript denotes observation i. An estimated error is calculated for each

observation. This allows the information in each observation to be used in the estimation

procedure. Recall, from earlier readings, this is an important property of OLS.

To recap, using the above example, we have the following information, 1) paired

observations on y and x, 2) the total number of observations is n, 3) a simple functional form

given by yi = a + bxi + ui, 4) a and b are unknown parameters, but are fixed (that is they do not

vary by observation), 5) a definition for an error term, 6) the objective to minimize the sum of

squared residuals, 7) one goal to use all observations in the estimation procedure, and 8) we will

never know the true values for a and b.

Minimize Sum of Squared Errors

To minimize the sum of squared residuals, it is necessary to obtain û i for each

observation. Estimated residuals are calculated using the estimated values for a and b. First,

using the estimated equation ŷ i â b̂x i , (recall the hat denotes estimated values) an estimated

value for y is obtained for each observation. Unfortunately, at this point we do not have values

for â and b̂ . As noted earlier, residuals are calculated as û i y i ŷ i . At this point, we have

values for all yi’s.

The sum of squared residuals can be written mathematically as

û 12 û 22 û 32 û 2n

(3)

n

û i2

i 1

where n is the total number of observations and ∑ is the summation operator. The above

equation is known as the sum of squared residuals (sum of squared errors) and denoted SSE.

Using the definitions of û i and ŷ i , the SSE becomes

(4)

n

n

n

n

i 1

i 1

i 1

i 1

SSE û i2 ( y i ŷ i ) 2 [ y i (â b̂x i )] 2 ( y i â b̂x i ) 2

where first the definition for û i is used, then the definition for ŷ i , and finally some algebra.

3

Up to this point, only algebra has been used to provide a definition for residuals and

provide an equation for the sum of squared residuals. Because the objective is to minimize the

sum of squared residuals, a procedure is necessary to achieve this objective. Recall from the

calculus review, a well-behaved function can be maximized or minimized by taking the first

derivatives and setting them equal to zero. Second order conditions are then checked to

determine if a maximum or minimum has been found.

An equation of the objective function for the OLS estimation procedure is:

n

min SSE ( y i â b̂x i ) 2

(5)

i 1

with respect to (w.r.t.) â and b̂ .

KEY POINT: Students at this point often face a mental block. Minimizing this equation w.r.t.

â and b̂ is no different than minimizing equations seen in the review of calculus. The mental

block occurs because earlier, the minimization was w.r.t. x and not the parameters, â and b̂ .

Calculus does not depend on what the variable of interest is called. Do not change the procedure

and ideas, just because the variables of interest are now called â and b̂ and not x. This is simply

a nomenclature issue.

Estimates for a and b are obtained by minimizing the SSE as follows 1) take the first

order partial derivatives w.r.t. â and b̂ , 2) set the resulting equations equal to zero, 3) solve the

first order conditions (FOC) for â and b̂ , and 4) check the second order conditions for a

maximum or minimum. Notice this procedure is no different than the procedure reviewed

earlier. Taking the first order partial derivatives w.r.t. â and b̂ and setting them equal to zero, the

following two equations are obtained:

SSR

(6)

SSR

â

n

n

i 1

i 1

[2 ( y i â b̂x i ) (1)] 2( y i â b̂x i ) 0, and

n

n

i 1

i 1

b̂ [2 ( y i â b̂x i ) ( x i )] 2x i ( y i â b̂x i ) 0.

Two equations with two unknowns, â and b̂ , are obtained from the first order conditions.

Solving these equations for â and b̂ one obtains the following expressions for the values of

â and b̂ that minimize the SSE. From the first order conditions (equation 6), the following

general expressions are obtained for the OLS estimators (see tables 1 and 2 for steps involved):

4

â y b̂x

(7)

b̂

n

n

n

i 1

i 1

n

i 1

n x i yi x i yi

n

.

n x i2 ( x i ) 2

i 1

i 1

Table 1. Algebraic Steps Involved in Obtaining the OLS Estimator, â , from the

FOC Conditions

Mathematical Deviation

Step involves

Original FOC

2( y â b̂x ) 0

( y â b̂x ) 0

y â b̂x 0

Divide both sides by -2

y

Summation over a constant

i

i

i

i

i

i

Distribute the summation operator

i

n â b̂ x i 0

nâ y i b̂ x i

Subtraction

1

1

y i b̂ x i

n

n

â y b̂x

Divide by n

â

Definition of a mean

Table 2. Algebraic Steps Involved in Obtaining the OLS Estimator, b̂ , from the

FOC Conditions

Mathematical Deviation

Step involves

Original FOC

2x i ( y i â b̂x i ) 0

Divide both sides by -2

x ( y â b̂x ) 0

i

i

i

x y âx b̂x x

i

x y

x y

i

i

i

i

i

i

0

â x i b̂ x i2 0

Distribute the summation operator

and xi

Summation over a constant

1

1

Substitute the definition for the â

y i b̂ x i ] x i b̂ x i2 0

n

n

Use the distributive law and then

1

1

x i y i n y i x i b̂[ n x i x i x i2 ] 0 factor out b̂ , careful with the

negative and positive signs

1

Solve for b̂

x i yi n yi x i

b̂

1

x i x i x i2

n

i

i

[

5

b̂

n x i y i x i y i

Simplify

n x i2 ( x i ) 2

Example. At this point, returning to the example will help clarify the procedure. There are three

paired observations on x and y, (3, 40), (1, 5), and (2, 10). Using these data points, the SSE can

be written as

(8)

3

3

3

i 1

i 1

i 1

SSE û i2 ( y i ŷ i ) 2 ( y i â b̂x i ) 2

(40 â b̂(3)) (5 â b̂(1)) 2 (10 â b̂(2)) 2

2

Taking the partial derivative of equation (7) w.r.t. â and b̂ and setting the resulting equations

equal to zero, the following first order conditions are obtained:

SSR

(9)

SSR

â

b̂

2(40 â b̂(3)) 2(5 â b̂) 2(10 â b̂(2)) 0

6(40 â b̂(3)) 2(5 â b̂) 4(10 â b̂(2)) 0.

Solving these two equations for the two unknowns, â and b̂ , one obtains the OLS estimates for a

and b given the three paired observations. The first equation in equation 9 can be simplified as:

(10)

80 2â 6b̂ 10 2â 2b̂ 20 2â 4b̂ 0

110 6â 12b̂ 0.

Similarly, the second equation in equation (6) can be simplified as:

(11)

240 6â 18b̂ 10 2â 2b̂ 40 4â 8b̂ 0

290 12â 28b̂ 0

One way of solving these two equations is to multiplying equation (10) by 2 and then setting

equations (10) and (11) equal to each other. Another way is to solve one equation for b̂ or â

and substitute into the other equation. Both methods will give the same answer. Solving the

equations, one obtains the OLS estimate for a (note both equations are equal to zero and

multiplying both sides by two will not affect the equality):

290 12â 28b̂ 0 2(110 6â 12b̂) 220 12â 24b̂

70 4b̂ 0

b̂ 70 17.5

4

6

Substituting this result into either equation (10) or (11), the OLS estimate for a is obtained:

110 6â 12(70 ) 0

4

110 3 * 70

â

100 / 6 16.67.

6

The OLS estimates for this example are, therefore, â 16.67 and b̂ 17.5 . Given the original

simple linear equation and the three data points, an intercept of -16.67 and a slope of 17.5 are

obtained; giving the following estimated line ŷ 16.67 17.5x .

The following information can be in the general formulas to obtain the OLS estimates.

These general formulas, avoid having to solve the FOC using the data observations.

yi

xi

xiyi

x2i

40

3

120

9

5

1

5

1

10

2

20

4

Summation

55

6

145

14

Mean

18.333 2

Using this information, the following equations are obtained:

n

(12)

b̂

n

n

i 1

n

i 1

n x i yi x i yi

i 1

n

n x i2 ( x i ) 2

i 1

3(145) 55(6) 435 330 105

17.5

42 36

6

3(14) (6) 2

i 1

â y b̂x 18.333 17.5(2) 18.333 35 16.67

Using the estimated equation, estimated errors for each observation are:

û 1 40 (16.67 17.5(3)) 40 35.83 4.17

(12)

û 2 5 (16.67 17.5(1)) 5 .83 4.17

û 3 10 (16.67 17.5(2)) 10 18.33 8.33.

Second Order Conditions

As with all maximization and minimization problems, the second order conditions (SOC)

need to be checked to determine if the point given by the FOC conditions is a maximum or

minimum. The OLS problem will provide a minimum. Intuitively, a minimum is achieved

because the problem is to minimize the sum of squares. Squaring each residual forces each term

to be nonnegative. The problem becomes then minimizing the sum of nonnegative numbers.

Because all numbers are nonnegative, the smallest possible sum is zero. A zero sum occurs

when all residuals equal zero. This would be a perfect between the line and the data points. In

empirical studies, a perfect will not occur. A residual that is positive will add to the sum of the

7

squares. Thus, the sum of squared residuals must equal a zero or a positive number. This

intuitive explanation indicates the problem will provide a minimum.

In figure 2, the general minimization problem is shown graphically (note, in the figure the

intercept is b1 instead of a and the slope parameter is b2, do not let the change in notation confuse

you. An unknown variable can be called anything. This is the only good figure I could find).

For different estimates for a and b, the SSE is graphed. Notice the SSE varies as the estimates

for the intercept and slope change. Of importance here is the shape of the minimization problem.

Notice, the bowl shaped function. Such a shape assures the SOC will be satisfied.

Mathematically, the FOC for minimization of the SSE finds the lowest point on the SSE graph.

The SOC confirm the point is a minimization.

To use the simple second order condition test from the calculus review section of the

class, the second and cross partial derivatives are necessary. Recall, the incomplete test required

for a minimum the second order partials to be greater than zero and the two cross partials

multiplied together must be greater than the cross partials squared. The necessary partial

derivatives are:

2 SSR

(13)

2 SSR

2 SSR

n

â

2

2 2n 0.

i 1

n

b̂ 2

n

2x i2 2 x i2 0

âb̂

i 1

i 1

n

n

i 1

i 1

2 x i 2 x i .

The second order partials are greater than zero, because only nonnegative numbers are involved.

An observation on the variable, x, maybe negative, but squaring x results in a positive number.

Further, it can be shown (although not intuitively) that 2n(2 x i2 ) (2 x i ) 2 . This equation

holds partially because one side of the equation is multiplied by the number of observations.

Example Continued. Continuing the example, it is necessary to check the second order

conditions. Recall, the three-paired observations on x and y are (3, 40), (1, 5), and (2, 10).

Using these data points, the SOC are:

2 SSR

2 SSR

SSR

n

â

2

2 2n 2(3) 6 0.

i 1

b̂ 2

2

n

n

i 1

i 1

2x i2 2 x i2 2(3 2 12 2 2 ) 28 0

( SSR

2

â

2

b̂

2

2

) ( SSR

âb̂

) 2 6(28) (2(3 1 2)) 2 168 144

Therefore, the second order conditions hold and the OLS estimates minimized the SSE w.r.t.

â and b̂ .

8

In figure 3, the minimization problem is shown graphically for our simple threeobservation example. For different estimates for a and b, the SSE is graphed. Notice the SSE

varies as the estimates for a and b change. As the estimates for a and b move away from the

OLS estimates of -16.67 and 17.5, the SSE increases.

KEY POINT: although often seen as using new ideas, the derivation of the OLS estimator uses

only simple algebra and the idea of minimization of a quadratic function. This is material that

was covered in the prerequisites for this class and reviewed in previous lectures. What is new is

the combining of the subject matters of economics (for the problem), algebra (model set up), and

calculus (minimization) to obtain the OLS estimates for a simple linear equation. Another point

other seen as a problematic is that in previous classes, algebra was used to find x and y with a

and b as given constants. In econometrics, the x’s and y’s are given constants and estimates for a

and b are obtained.

KEY POINT: two assumptions are implicit in the previous derivation of the OLS estimator.

First, the original problem assumed the equation to be estimated was linear in a and b. Second, it

was assumed the FOC could be solved. Neither assumption is particularly restrictive. Notice,

the assumptions say nothing about the statistical distribution of the estimates, just that we can get

the estimates. One reason OLS is so powerful is that estimates can be obtained under these fairly

unrestrictive assumptions. Because the OLS estimates can be obtained easily, this also results in

OLS being misused. The discussion will return to these assumptions and additional assumptions

as we continue deriving the OLS estimator.

Algebraic Properties of the OLS Estimator

Several algebraic properties of the OLS estimator are shown here. The importance of

these properties is they are used in deriving goodness-of-fit measures and statistical properties of

the OLS estimator.

Algebraic Property 1. Using the FOC w.r.t. â it can be shown the sum of the residuals is equal

to zero:

2( y

(14)

i

â b̂x i ) 0

i

n

2 û i 0 û i 0.

i

i 1

Here, the first equation is the FOC derived earlier. The definition for the residuals

(û i y i â b̂x i ) is substituted into the FOC equation. The constant, -2, is then removed from

the summation. Because the constant 2 does not equal zero, the only way the FOC can equal

zero is the sum of the residuals equal zero. The sum of the residuals equally zero, implies the

mean of the residuals must also equal zero.

9

Algebraic Property 2. The point ( y, x ) will always be on the estimated line. Using the FOC

w.r.t â , this property can be shown by dividing both sides by -2, distributing the summation

operator through the equation, divided both sides by the number of observations, and then

simplifying by using the definition of a mean. Mathematically this property is derived as

follows,

2( y

i

â b̂x i ) 0

i

y

â b̂x i y i nâ b̂ x i 0

i

i

y

(15)

i

i

i

â b̂

x

n

n

y â b̂x 0

i

i

i

0

n

y â b̂x.

Algebraic Property 3. The sample covariance between the xi and û i is equal to zero. Recall, the

formula for calculating the covariance between any two variables, z and q is

n

cov

(z

i 1

i

z )(q i q )

. To show this property, the FOC w.r.t. b̂ is used. By substituting in the

n 1

definition for the residuals, the FOC can be simplified to:

2( y

(16)

i

â b̂x i ) x i 0

i

û x

i

i

0

i

Substituting this result, along with the algebraic property 1, the sum and mean of the residuals

equal zero into the covariance formula, algebraic property 3 is derived:

cov( x , û )

(17)

(x

x )( û i û )

n 1

x i u i x i û xû i xû

i

n 1

0 0 x i x 0 nx 0

x u

i

i

û x i x û i nxû

n 1

0.

n 1

This shows the covariance between the estimated residual and the independent variable is equal

to zero.

Algebraic Property 4. The mean of the variable, y, will equal the mean of the ŷ . Distributing

the summation operator through the definition of the estimated residual, using algebraic property

10

1, and the definition of a mean are used to show this property. Mathematically, this is property is

derived as:

û i y i ŷ i

y i ŷ i u i

(18)

y ŷ û

y ŷ

i

i

i

n

y ŷ.

i

.

i

n

Example Continued. Using the previous three-observation example, it can be shown the four

algebraic properties hold.

Algebraic Property 1. Using the residuals calculated earlier, the sum of the residuals is SSE =

4.17 + 4.17 - 8.33 = .01 which within rounding error equals zero.

Algebraic Property 2. Substituting in the mean of the x’s, 2, into the estimated equation, one

obtains y = -16.65 + 17.5 (2) = 18.33, which equals the mean of the y variables, 18.33 = (40 + 5

+ 10)/3.

Algebraic Property 3. The covariance between x and û is given by

(3 2)( 4.17 0) (1 2)( 4.17 0) (2 2)( 8.33 0)

3 1

1(4.17) 1(4.17) 0(8.33)

0.

2

Thus, property 3 holds.

Algebraic Property 4. Using earlier calculations for obtaining the estimated y’s, the mean of the

estimated y’s can be obtained using the equation (35.83 + 0.83 + 18.33)/3 = 18.33. Thus, the

mean of y and ŷ are equal.

KEY POINT: in deriving these algebraic points, subject matter (definitions of mean and

covariance) that pertains to statistics has been added to the mix of economics, calculus, and

algebra.

Goodness-of-Fit

Up to this point, nothing has been stated about how “good” the estimated equation fits the

observed data. In this section, one measure of the goodness-of-fit is presented. This measure is

11

called the coefficient of determination or R2. The coefficient of determination measures the

amount of the sample variation in y that is explained by x.

To derive the coefficient of determination, three definitions are necessary. First, the total

sum of squares (SST) is defined as the total variation in y around its mean. This definition is

very similar to that of a variance. SST is defined as

n

(19)

SST ( y i y) 2 .

i 1

Notice, this formula is the same, as the formula for a variance except the variation is not divided

by the degrees of freedom. We will return to this point later in the lectures. The second need is

the explained sum of squares (SSR) or sum of squares of the regression (where the R comes

from). SSR is simply the variation of the estimated y’s around their mean. SSR is defined as:

n

(20)

SSR ( ŷ i y) 2 .

i 1

Recall, the actual values for y and the estimated values for y have the same mean. Therefore,

equations (19) and (20) are the same except for actual or estimated y’s are used. The means are

the same. The third definition is the residual sum of residuals (errors) (SSE), which was earlier

defined as:

n

(21)

SSE û i2 .

i 1

SSE is the amount of variation not explained by the regression equation.

It be shown the total sum of the variation in y around its mean is equal to the amount of

variation in y around its mean plus the amount of variation not explained. Mathematically, this

statement is SST = SSR + SSE. To show this equation holds, algebraic properties (1) and (3)

derived earlier must be used. Using these two properties, and expanding the SST equation, the

necessary steps to show this equation holds are shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Algebraic Steps Involved in Showing the Equation SST = SSR + SSE Holds

Mathematical Deviation

Step involves

2

Original equation

SST ( y i y)

[( y i ŷ i ) ( ŷ i y)] 2

Add ŷ i and subtract ŷ i

[û i2 2û i ( ŷ y) ( ŷ y) 2 ]

Expand

[û i ( ŷ i y)] 2

û i2 2 û i ( ŷ i y) ( ŷ i y)

SSE 2 û i ( ŷ i y) SSR

Use the definition û i y i ŷ i

2

Distribute the summation operator

Using sum of square definitions

12

?

2 û i ( ŷ i y) 0

Need to show middle term equals

zero

?

2 [û i (â b̂x i y) 2 [û i â û i b̂x i û i y] 0

Use definition ŷ i â b̂x i

?

â û i b̂ û i x i y û i 0

Divide by 2 and distribute the

summation operator

Using algebraic properties 1 and 3

â 0 b̂0 y0 0

SST = SSR + SSE

Equation shown

From the equation SST = SSR + SSE, the coefficient of determination can be derived.

Taking this equation and dividing both sides by SST one obtains:

(22)

SST

SST

SSR

SST

SSE

SST

1.

This equation is equal to one because any number divided by itself equals one. Rearranging this

equation the coefficient of determination is obtained:

(23)

R 2 SSR

SST

1 SSE

SST

.

As shown in this equation, the coefficient of determination, R2, is the ratio of the amount

of variation explained to the total variation in y around its mean, or equivalently, the one minus

the ratio of the amount of variation not explained to the total variation. Thus, R2 measures the

amount of sample variation in y that is explained by x. R2 can range from zero (no fit) to one

(perfect fit). If x explains no variation in y, the SSR will equal zero. Looking at equation (23), a

zero for SSR gives a value of zero for R2. On the other hand, if x explains all the variation in y,

SSR will equal SST. In this case, R2 equals one. The values of [0 - 1] are just the theoretical

range for the coefficient of determination. One will not usually see either of these values when

running a regression.

The coefficient of determination (and its adjusted value discussed later) is the most

common measure of the fit of an estimated equation to the observed data. Although, the

coefficient of determination is the most common measure, it is not the only measure of the fit of

an equation. One needs to look at other measures of fit, that is don’t use R2 as your only gauge

of the fit of an estimated equation. Unfortunately, there is not a cutoff value for R2 that gives a

good measure of fit. Further, in economic data it is not uncommon to have low R2 values. This

is a fact of using socio-economic cross-sectional data. We will continue the discussion on R2

later in this class, when model specification is discussed.

Example Concluded. To finish our example, we need to calculate SST, SSR, and SSE, along

with the coefficient of determination. Using the residuals calculated earlier, SSE equals

SSE = (4.17)2 + (4.17)2 + (-8.33)2 = 104.17.

13

The estimated y values calculated and means earlier are used to obtain SSR:

SSR = (35.83 - 18.33)2 + (0.83 - 18.33)2 + (18.33 - 18.33)2 = 612.5.

Using the actual observations on y, SST equals:

SST = (40 - 18.33)2 + (5 - 18.33)2 + (10 - 18.33)2 = 716.67.

Thus, the coefficient of determination is

R2 = 612.5 / 716.67 = 0.85 or

R2 = 1 - (104.17 / 716.67) = 0.85.

In our example, the amount of variation in y around its mean explained by the estimated equation

is 85%.

Important Terms / Concepts

Error Term

Residual

Deviation

Estimated error term

Hat symbol

Sum of squares

SSR

SST

SSE

Why OLS is powerful?

Why OLS is misused?

Four Algebraic properties

Goodness-of-fit

R2 - Coefficient of Determination

Range of R2

n

i

14

Linear Equation Review

Linear equations are simply equations for a line. Recall, from algebra, an equation

given by y = α + βx has a y-intercept equal to α and a slope equal to β. The y-intercept

gives the point where the line crosses the y-axis. If the intercept is 10, the line will cross

the y-axis at this value. Crossing the y-axis indicates a x-value of zero, therefore, the (x, y)

point (0, 10) is associated with this line. The slope indicates the rise and run of the line. A

slope equal to five indicates y increases by five units (the line rises five units) for each oneunit increase in x (a one unit increase in x). A positive slope indicates the line is upward

sloping, whereas a negative slope indicates a downward sloping line. Which of the

following equations are linear in x and y?

y 4 3x

y a 6x 3x 2

y a 5 ln x

Only the first equation is linear in y and x. The second equation contains an x-squared

term. This equation is a quadratic equation. The third equation is also is not a linear

equation in x and y; here the natural logarithm of x is in the equation. This equation is

commonly known as a semi-log equation. However, each equation remains linear in the yintercept and slope parameters.

Of the following equations, which one(s) are linear in the y-intercept and slope parameters?

y 5 2 x

y x

y ln ln x

Here, none of the equations is linear in the y-intercept and slope parameters. Each equation

contains a nonlinear component associates with at least one of the parameters. Linear in

parameters is given by

y x.

As a final example, the following two equations are linear in the y-intercept and slope

parameters (α and β), but nonlinear in x

y ln x

y x 2 .

15

45

Estimated

Observed

40

}u 1

35

30

25

20

}

15

u3

10

u2{

5

0

0

0.5

1

1.5

2

2.5

3

Figure 1. Relationship Between Estimated Equation and

Observed Value, Residuals

3.5

16

Figure 2. General simple linear regression problem of minimizing the sum of squared

errors w.r.t. the intercept (b1) and slope (b2) parameters. Note in the notation in the text, a

denotes the intercept and b denotes the slope.

17

Figure 3. Graph showing the minimization of the sum of squared errors for the simple

linear regression example

100000

75000

SSE

50000

25000

0

-20

50

0

0

20

-50

40

b

60

-100

a