Permanent Press and Other Formaldehyde Treated Fabrics

advertisement

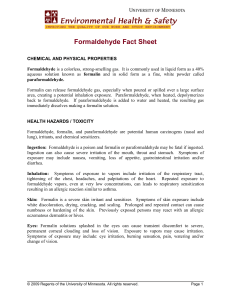

PERMANENT PRESS AND OTHER FORMALDEHYDE TREATED FABRICS Employees working in clothing manufactures with fabrics treated with formaldehyde-treated resins develop irritation of the respiratory system. Exposure levels to formaldehyde there were 1-11 ppm formaldehyde, and employees hands became contaminated with the resin.1 An investigation of eight textile plants using formaldehyde resin for permanent press treatment with average formaldehyde exposure of 0.8 ppm found health effects of respiratory irritation, increased thirst and sleep disturbance.2 Another survey of employees processing textiles impregnated with urea-formaldehyde and melamine-formaldehyde resins, with exposures up to 5 mg/m3, found irritation conjunctivitis in 72%, inflammatory rhinitis in 28%, red dry skin in 11% and chronic bronchitis in 22%3 A Permanent Press clothing factory inspection in California found formaldehyde exposures of 0.9 to 2.7 ppm, and employees had increased tearing of the eyes and irritation of the throat and nasal passages.4 Many reports exist for cases of contact dermatitis among workers in textile plants using fabrics treated with formaldehyde resins3 Nineteen cases of eczema have been reported in people wearing permanent press treated fabrics.5 Dress shop employees and customers studies where formaldehyde treated fabrics were sold had increased burning eyes, headaches, and nose and throat irritation. Formaldehyde levels were 0.13 to 0.45 ppm, and 15 air changes/hour in increased ventilation was recommended to remedy the problem.6 Formaldehyde resins are often used in the textile industry to reduce wrinkling and shrinkage. The types of resins used include urea-formaldehyde, melamine-formaldehyde and phenol-formaldehyde.7 The Consumer Product Safety Commission has also identified permanent press clothing as “products in which formaldehyde is used”.8 Formaldehyde has been associated with illness symptoms including headache, eye and respiratory irritation, sleep disturbance and increased thirst in workers with occupational exposure as well as people with certain consumer products at exposure levels as low as 0.13 ppm.9 Chronic exposure to formaldehyde can cause asthmatic symptoms and other reactive airway disease10, headache, memory loss, dizziness, upper and lower airway effects, aching, gastrointestinal disturbances, chronic fatigue, and increased sensitivity to chemicals.11,12,13 3 Day care workers exposed to levels of 0.43 mg/m (about 0.34 ppm) experienced headache, eye and respiratory irritation and fatigue.14 Boeing workers exposed to formaldehyde resins had fatigue, impaired memory, headache, confusion and respiratory effects.15 A home resident exposed to formaldehyde (UFFI insulation) developed respiratory problems and new onset of sensitivity to chemicals.16 Chronic formaldehyde exposure in mobile home residents at levels of 0.05 to 0.5 ppm also induced chronic multiple organ system symptoms similar to those described in the literature for multiple chemical sensitivity.8 Immune changes have also been reported with formaldehyde exposure. Changes in cell-mediated immunity can include changes in basophiles and/or suppressor cells.17 Chronically ill persons after formaldehyde exposure often exhibit immune activation and increased autoantibodies.3,8 Mobile home residents with chronic exposure at 0.05 to 0.5 ppm exhibited increased immune activation (increased Permanent Press and Other Formaldehyde Treated Fabric Page 2 TA1), increased autoantibodies, and (as a group) increased antibodies against formaldehyde (anti HCHO-HSA).8 Another mobile home group with exposures of 0.07 to 0.55 ppm found reduced T lymphocytes and impaired T cell function using PHA.11 However, since immune responses change with the time lapse from the initiating exposure, the individual patient abnormalities will be in part determined by how soon they were tested following the causal exposure. Liver effects can also develop from formaldehyde exposure.12 These include toxic hepatitis and symptoms of hypersensitivity which developed in a family exposed up to 0.95 ppm; a 10 year old who developed jaundice and liver enzyme changes with exposures in a mobile home up to 10 ppm; and a home occupant exposed to 10 ppm who developed hepatitis, respiratory problems and a newly induced sensitivity to chemicals. Brain effects have also been reported from formaldehyde exposure. Neurobehavioral testing on 305 histology technicians with an average of 17 years in the occupation using formaldehyde as a fixative an average of 4.3 hours daily had impaired memory, dexterity and balance.13 This study controlled statistically for solvent exposure that at lab levels affected only recall. Since the study was conducted on actively employed technicians, it could not rule out permanent damage. Exposure levels in the areas of greatest exposure were 0.2 to 1.9 ppm, but technicians did not spend the full day in these areas. Another evaluation of four formaldehyde-exposed employees18 showed, compared to healthy controls, they had excess fatigue, headache, sleep disturbance, irritability and mood changes. Neurologic and neurocognitive functions were impaired also on standardized testing, including balance, reaction time, color visual fields and multiple tests of cognitive function. These persons were examined four years or longer after last exposure; therefore changes seen demonstrate permanent brain damage. Insulators using formaldehyde-containing insulation19 were found to have impairment on lung function compared to controls, including worse FEV1, FEV75-85 (small airway disease), vital capacity (FVC) and/or gas transfer ability (diffusing capacity). Formaldehyde could cause nervous system damage by its known ability to react with and form crosslinking with proteins, DNA and unsaturated fatty acids.13 These same mechanisms could cause damage to virtually any cell in the body, since all cells contain these substances. Formaldehyde can react with the nerve protein (neuroamines) and nerve transmitters (e.g., catecholamines)13, which could impair normal nervous system function and cause endocrine disruption. Increases in temperature (hot days, ironing coated textiles) and increased humidity both increase the release of formaldehyde from coated textiles. Animals can be exposed to formaldehyde and sensitized so that thereafter they have abnormal responses both to low levels of formaldehyde and to multiple other pollutants, i.e., they develop sensitivity to multiple chemicals.20 Permanent Press and Other Formaldehyde Treated Fabric Page 3 1 Ettinger I, Jeremias, M., “A study of the health hazards involved in working with flame proofed fabrics”, NY State Dept. Labor, Div. Ind Hyg Rev 34: 25-27, 1955. 2 Shipkovitz, H.D., “Formaldehyde vapor emissions in the permanent-press fabrics industry”, Report No. TR-52. Cincinnati, US Dept Health, Education and Welfare, Sept. 1968. 3 NIOSH Criteria for a Recommended Standard: Occupation Exposure to Formaldehyde. USDHEW, Dec. 1976, p.40. 4 Blejer, W.P., Miller B.H., “Occupational health report of formaldehyde concentrations and effects on workers at the Bayly Manufacturing Company, Visalia, CA. Report Nbr 5-1806. California Dept. of Health, Los Angeles, 1966. 5 Skogh M., “Axillary eczema in women, a syndrome” Aeta Derm Venereol 39: 369-391, 1959. 6 Bourne, H.G., Seferian, S. “Formaldehyde in wrinkle-proof apparel produced tears for milady”, Ind Med Surg 28: 232-233, 1959. 7 Berrens, L. etal., “Free formaldehyde in textiles in relation to formalin contact sensitivity” 8 Alert Sheet from the Consumer Product Safety Commission, March 1980. 9 Criteria for a Recommended Standard: Occupational Exposure to Formaldehyde. USDHEW, Dec 1976. 10 Nordman H., etal. “Formaldehyde asthma - rare or overlooked?” J. Allergy Clin Immunol 75: 81-99, 1985. 11 Broughton A, Thrasher JD “Antibodies and altered cell mediated immunity in formaldehyde exposed humans,” Comments Toxicol 2: 155-170, 1988. 12 Thrasher JD etal., “Building related illness and antibodies to albumin conjugates of formaldehyde, toluene disocyanate and trimellitic anhydride”, Amer J. Ind. Med 15: 187-195, 1989. 13 Thrasher JD etal., “Immune activation and autoantibodies in humans with long-term inhalation exposure to formaldehyde,” Archive Env. Health 45: 217-223, 1990. 14 Olsen JH and Dossing M., “Formaldehyde induced symptoms in day care centers,” Am Ind. Hyg Ass. J. 43: 366-370, 1982. 15 Grammer L.C., etal., “Clinical and immunologic evaluation of 37 workers exposed to gaseous formaldehyde,” J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 86: 177-181, 1990. 16 Thrasher J.D., etal., “Antibodies and immune profiles of individuals occupationally exposed to formaldehyde: six case reports,” Amer J. Ind. Med. 14: 479-488, 1988. 17 Pross H.F. etal., “immunologic studies of subjects with asthma exposed to formaldehyde and area-formaldehyde (UFFI) off-products.” J. Allergy Clin Immunolo 79: 787-810, 1987. 18 KH Kilburn, “Neurobehavioral impairment and seizures from formaldehyde”, Archiv Env. Health 49: 37-44, 1994. 19 KH Kilburn, “Pulmonary and neurobehavioral effects of formaldehyde exposure”, Archiv Env. Health 40: 254-260, 1985. 20 Wiglusz R. etal., “Effect of environmental conditions on re-emission of formaldehyde from textile materials”, Bull Inst. Marit Trop Med Gdyni 46: 53-58, 1945.