Introduction to pediatric dentistry

advertisement

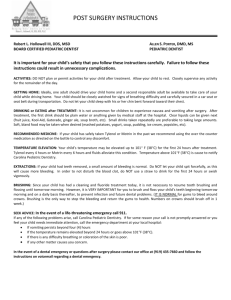

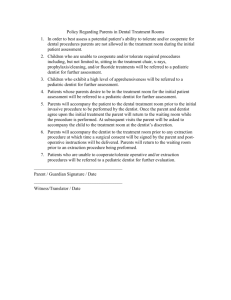

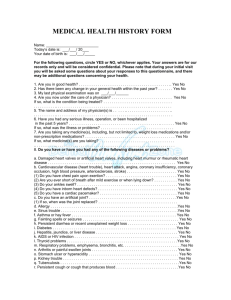

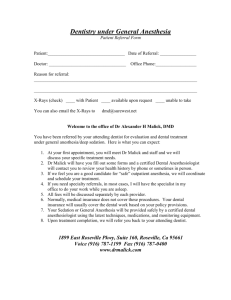

Chapter 1 Introduction to pediatric dentistry 1 Definition of pediatric dentistry According to AAPD(America Academy of Pediatric Dentistry), Pediatric dentistry is an age-defined specialty that provides both primary and comprehensive preventive and therapeutic oral health care for infants and children through adolescence, including those with special health care needs. The definition gives us answers for the following questions: a. Who are the objects of Pediatric dentistry? Infants and children through adolescence including those with special health care needs b. What does the Pediatric dentistry provide? Provides both primary and comprehensive preventive oral health care Provides both primary and comprehensive therapeutic oral health care c. What are the key elements of this definition that make it so unique? “age-defined”: most specialties are procedure defined (endodontics, periodontics, etc.). Pediatric dentists provide care for their specific age group of patients. There is no limitation to what type of treatment they provide. “primary and comprehensive...care”: Pediatric dentists are primary providers. There is no need for a referral of patients. Parents can choose to have their children evaluated and treated by a pediatric dentist just like they can choose to have their child treated by a pediatrician. “infants and children through adolescence”: Pediatric dentists see patients at any age from birth up to their late teens. “special health care needs”: Pediatric dentists have the training and experience to evaluate and treat patients, that are medically compromised. This includes patients with hemophilia, leukemia, congenital syndromes, etc... No other dental specialty, other than OMS is more involved in hospital care of patients. We’ve talked about the four key elements in the definition that make the Pedodontics so unique, now if you find the Pedodontics has its sunshinning future, and welcome you join us and become one of pediatric dentist. 2.Structure of the dental consultation The way a dentist interacts with patients will have a major influence on the success of any clinical or preventive care. It is particularly important for pediatric dentists to learn how to communicate with children, and how to help anxious and uncooperative children relax, as communicating effectively is of great value to reduce the stress involved when offering clinical care, and failure to communicate will result in disappointed children and an unsuccessful practice. So, the training of pediatric dentistry should include a thorough understanding of how the dental visit should be structured, and what strategies are available to help children cope with their apprehension about dental procedures. Each patient is a unique individuals with different needs and aspirations, this is especially so in pediatric dentistry where a clinician may have to treat a frightened 3-year-old child at one appointment and an hour and a half later be faced with the problem of offering preventive advice on oral health to a 15 year old. So, only an outline structure is given to a successful dental consultation. 2.1 Greeting. First, as a pediatric dentist, you should greet the child in a friendly way, smiling and looking steadily at him/her. Second, it is better for you to greet the child by name, especially when he/she is recalled . It’s an honor for a person whose name is born in mind by another person. Third, you should remember that proceeding too quickly to an instruction could spoil a greeting. For example, ‘Hello, qing, jump in the chair‘ is rather abrupt and may prejudice an interactive relationship. The greeting should be used to put the children and parents at ease before proceeding to the next stage. 2.2 Preliminary chat. This phase has three objectives, to assess whether the patients have any particular worries or concerns, to settle the patient into the clinical environment, and to assess the patient’s emotional state. The following sequence represents one way of maximizing the effect of the ‘preliminary chat’: (a) Begin with non-dental topics. For child who never comes before, you may express your praise to him/her. For example, you may say‘ oh, your eyes so beautiful’ or ‘ you are so clever’ and so on. For children who have been before, it is helpful to record useful information such as toys, school and hobbies. (b) Ask an open question such as ‘How are you/are you having any problems with your teeth?’ (c) Listen to the answer. It is important to listen to the answer and probe further if necessary. All too often dentists ask questions and then ignore the answer. By talking generally and taking note of what the child is saying you are offering a degree of control and reducing anxiety. 2.3 Preliminary explanation In this stage the aim is to explain what the clinical or preventive objectives are in terms that parents and children will understand. This is a vital part of any visit as it establishes the credibility of the dentist as someone who knows what the ultimate goal for the treatment is, and is prepared to take the time and trouble to discuss it in non-technical language. It must be stressed that sensible information cannot be offered to the patient or parents until the clinician has a full history and a treatment plan based on adequate information. This requires a broad view of the patient and should not be totally tooth-centered. It is all too easy to lose the confidence of parents and children if you find yourself making excuses for clinical decision taken in a hurried and unscientific manner. 2.4 Business. The patient is now worked on. Many jokes are made about dentists who ask questions of patients who are unable to reply because of a mouthful instruments! This does not mean that the visit should enter a silent phase. It is important to remain in verbal contact. Check the patient not in pain, discuss what you are doing, use the patient’s name to show a personal interest, and clarify any misunderstandings. At the end of the business stage it is helpful to summarize what has been done and offer aftercare advice. If the parent is not present in the surgery, the treatment summary is particularly important, as it is useful way of maintaining contact with the parents. 2.5 Health education. To a large extent, oral health id dependent upon personal behavior and as such it would be unethical for dentists not to include advice on maintaining a healthy mouth. The final part of the health education activity is goal setting. The dentist sets out in simple terms what the patient should try and achieve by the next visit. It implies a form of contract and as such helps both children and parents to gain a clearer insight into how they all can help to improve the child’s oral health. Goal setting must be used sensibly. 2.6 Dismissal. This is the final part of a visit and should be clearly signposted so that everyone knows that the appointment is over. The patient should be addressed by name and a definite farewell offered. The objectives should be ensured that wherever possible the patient and parents leave with a sense of goodwill. Clearly, not all appointment sessions can be dissected into these six stages. However, the basic element of according the patient the maximum attention and personalizing your comments should never be forgotten. 3 Anxious and uncooperative children 3.1 Dental anxiety is a common problem all over the world, especially in pediatric dentistry. Dental anxiety is a common problem all over the world, and it not only prevents many patients from seeking care but it also cause stress to the dentists undertaking dental treatment. Indeed one of the major sources of stress for general dental practitioners is ‘coping with difficult patients’. So dental anxiety is a problem that we as a profession must take seriously, especially as children remember pain and stress suffered at the dentist and carry the emotional scars into adult life. Some people may develop such a fear of dentistry that they are termed phobics. A phobia is an intense fear, which is out of all proportion to the actual threat. 3.2 How does the dental anxiety develop? Dental anxiety should be seen as a multi-factorial problem, and must also be seen as a continuum with fear—it is almost impossible to separate the two in much of the research undertaken in the field of dentistry, where the two words are used interchangeably. A number of theories have been suggested in an effort to explain the development of anxiety. (a) Uncertainty about what is to happen is certainly a factor, (b) A poor past experience with a dentist could upset a patient, © While others may learn anxiety response from parents, relations, or friends. 3.3 The extent of dental anxiety Research in this area suggests that the extent of anxiety a person experiences does not relate directly to dental knowledge, but is an amalgamation of personal experiences, family concerns, disease levels, and general personality traits. Such a complex situation means that it is no easy task to measure dental anxiety and pinpoint aetiological agents. 4 Helping anxious patients to copy with dental care 4.1 Establish an effective preventive programme Clearly, the easiest way to control anxiety is to establish an effective preventive programme so that children do not require any treatment. 4.2 Establish good dentist-patient relationship 4.3 Ensure any treatment is pain-free 4.4 Manage time effectively 4.5 Behavior Management A. Traditional Techniques a. Tell-show-do: to Reducing uncertainty The majority of young children have very little idea of what dental treatment involves and this will raise anxiety levels. Most children will copy if given friendly reassurance from the dentist, but some patients will need a more structured programme. One such structured method is the tell-show-do technique. As its name implies it centers on three phases: Tell: explanation of procedures at the right age/educational level. Show: demonstrate the procedure. Do: following on to undertake the task. Praise being an essential part of the exercise. b. Positive Reinforcement: During the treatment, first, you may find something to praise, it may be anything. Second, you should stress accomplishments and prizes at end of visit. c. Adaptive method d. Modeling: This makes use of the fact that individuals learn much about their environment from observing the consequences of other people’s behavior. You might repeat an action if we see others being rewarded, or if someone is punished we might decide not to follow that behavior. Modeling could be used to alleviate anxiety. If a child could be shown that it is possible to visit the dentist, have treatment, and then leave in a happy frame of mind, this could reduce anxiety due to ‘fear of the unknown’. It’s not necessary to use a live model, videos of co-operative patients are of value. e.Cognitive approaches Modeling helps people learn about dental treatment from watching others, but it does not take account of an individual’s ‘cognitions’ or thoughts. People may heighten their anxiety by worrying more and more about a dental problem so creating a vicious reinforcing circle. Thus there has been great interest in trying to get individuals to identify and then alter their dysfunctional beliefs. A number of cognitive modification techniques have been suggested, the most common ones including: *asking patients to identify their negative thoughts *helping patients to recognize their negative thoughts and suggesting more positive alternatives ‘reality based’; f. Distraction: This technique attempts to shift attention from the dental setting towards some other kind of situation. Distracters such as videotaped cartoons and stories have been used to help children cope with dental treatment. g. Voice control: Use the change of tone or inflection, volume to hold child’s attention, but do not telegraph frustration B. Adversive Techniques a. Physical restraint: Mouth Prop: Support oral access: Treatment aid Apply with care: Not to impinge on lips Not to subluxate mandible Assure ratchet works Open slowly Do not use as a crow-bar Wraps or Papoose Board Supports physically challenged patients, and it’s necessary during sedation, Downside : sense of helplessness, loss of control Pay attention to: Avoid injury Assure parental informed consent Meet community standards Hand over mouth C. Pharmacologic Techniques Sedation: Definition of Conscious Sedation: Minimally depressed level of consciousness that retains the patient’s ability to maintain a patent airway independently and continuously and to respond appropriately to physical stimulation and/or verbal command. Pay attention to: Strict guidelines requiring Monitoring & recording Recovery area Additional personnel General Anesthesia: Last resort Indications: Immaturity Extensive caries Physical or mental challenge Definition: Induced state of unconsciousness accompanied by loss of protective reflexes, including the ability to maintain an airway independently and respond appropriately to physical stimulation and/or verbal command First dental visit There seems to be a lot of confusion amongst parents, pediatricians, and dentists about the correct timing for the first dental visit. Many “family” dentists may tell parents not to bring children to their practice before they have all their primary teeth (age two or three), sometimes they even recommend to wait until age 6. The parent of a fearful or uncooperative child may be told “we have to wait until your child is old enough to sit still”. Under unfavorable circumstances delay of dental care can lead to catastrophic disease progression that is not in the best interest of the child. The AAPD recommends an initial postnatal oral evaluation within six months of the eruption of the first primary tooth and no later than twelve months of age. This means a child should have his or her first dental visit at the first birthday! At this examination visit the dentist should record a thorough medical and dental history. Parents should be prepared to review the prenatal, perinatal, and postnatal period of their child’s development. The oral examination at this early age is usually accomplished with the parent present in the office. It is most often only a visual exam. The child patient may be sitting in the parent’s lap with the head in the dentist’s lap (knee-to-knee position). One important aspect of this visit is to discuss the child’s risk of developing oral and dental disease. Based on this assessment the dentist will determine the appropriate recall interval for the next dental visit. In high risk cases this may be as early as three months. Dental decay in children can progress very rapidly. The dentist will also evaluate the child’s oral and dental development. The common question about “how many teeth at what age ?” will be addressed. The dentist will also evaluate the need for fluoride supplementation. It may be important to discuss non-nutritive habits (finger sucking, pacifier), injury prevention, oral hygiene, and effects of diet on the dentition. If treatment is indicated the dentist should be prepared to provide therapy or he needs to refer the patient.