Jean-Paul MENINGAUD, Poramate PITAK

advertisement

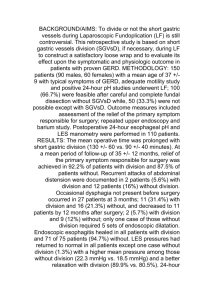

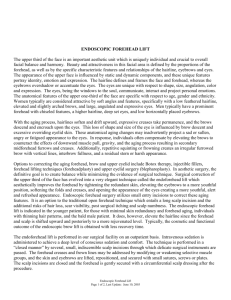

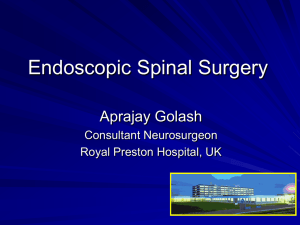

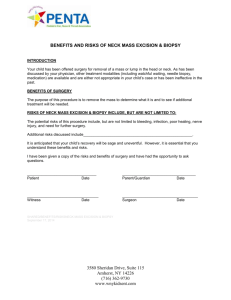

1 บทความที่ 2 (14 หน้า – 4 รู ปภาพ) ส่ วนที่ 1 ข้อมูลผูล้ งทะเบียนส่ งบทความ คานาหน้า : นาย ชื่อ-สกุล : ปรเมศร์ พิทกั ษ์อรรณพ คานาหน้า : Mr. (M.) ชื่อ-สกุล : Poramate PITAK-ARNNOP ที่อยูท่ ี่ติดต่อได้ : 34 Rue de Lübeck (porte 27) รหัสไปรษณี ย ์ : 75116 เมือง : Paris ประเทศ : France หมายเลขโทร. : 06 31 22 91 38 E-mail: dormigum@hotmail.com สาขาที่ศึกษา : วิทยาศาสตร์ ระดับการศึกษา: 3ème cycle – Hors programme communautaire (chirurgie maxillo-faciale) ชื่อสถาบัน : Service de Chirurgie maxillo-faciale, CHU Pitié-Salpêtrière, Faculté de Médicine, Université Pierre & Marie Curie (Paris VI), Paris, France ส่ วนที่ 2 ข้อมูลงานวิจยั /บทความ ชื่อบทความ : Endoscopic excision of forehead lipomas: a technical note (การผ่าตัดเนื้ องอกไลโพมาบริ เวณหน้าผากด้วยกล้องส่ อง-เทคนิควิธีการ) สาขาที่เกี่ยวข้อง: Clinical medical science (plastic and maxillofacial surgery) วิทยาศาสตร์ การแพทย์คลินิก (ศัลยศาสตร์ ตกแต่งและแม็กซิ ลโลเฟเชียล) ระดับการวิจยั : 3ème cycle – Docteur en médicine (chirurgie maxillo-faciale) คาหลัก : endoscopic surgery, lipoma, forehead, head and neck tumour รายละเอียด : รอการพิจารณาเพื่อตีพิมพ์ในในวารสาร International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 2 - Meningaud J-P, Pitak-Arnnop P, Rigolet A, Bertrand J-Ch. Endoscopic excision of forehead lipomas. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2005 (submitted) การประยุกต์ : 1.สามารถใช้บาบัดผูป้ ่ วยไทยในรายที่มีขอ้ บ่งชี้ เพื่อหลีกเลี่ยงผลไม่พึงประสงค์จากการผ่าตัดโดยเฉพาะการเกิดแผลเป็ น 2.สามารถประยุกต์เพื่อการวิจยั ศัลยกรรมบาบัดรอยโรคเนื้อเยื่ออ่อนลักษณะอื่นต่อไป 3.สะท้อนแนวคิดในการแก้ไขปั ญหาในการปฏิบตั ิงาน เพื่อให้เกิดผลการทางานที่มีประสิ ทธิ ภาพต่อไป 3 Endoscopic excision of forehead lipomas: a technical note Jean-Paul MENINGAUD, Poramate PITAK-ARNNOP*, Arnaud Rigolet, Jacques-Charles BERTRAND Department of Maxillofacial Surgery, Teaching Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital, Faculty of Medicine, University of Pierre & Marie Curie (Paris VI), 47 bd de l’hôpital, 75651 Paris, France *E-mail address: dormigum@hotmail.com Abstract Endoscopic surgery has largely taken the place of various procedures in craniomaxillofacial surgery. Our experiences in this technique we will present have proven useful in the resection of forehead lipomas. It magnification allows the better identification of lesions, or even small nerves, and vessels. The tumours were extracted without additional incisions. The result is at least equivalent with a greatly decreased incidence of scarring, and neurovascular injury of forehead. This technique has a steep learning curve. To our knowledge and experience, we believe that well-trained surgeons using the proper instruments can perform this manoeuvre with minimal trauma and few complications. Key words endoscopic surgery, lipoma, forehead, head and neck tumour 4 Introduction Clinically, lipoma presents as a soft, asymptomatic mass. Conservative excision is considered as the treatment of choice for this tumour, and recurrence is quite rare.[5] Simple direct approach to masses on the forehead always leaves obvious scars.[2] In an attempt to minimize the scarring, it has been more than 10 years since the endoscopic technique was first used in facial plastic and reconstructive surgery. At this time, the meaningful advantage offered by the endoscope has been a number of procedures, for instance, face lift, forehead lift, frontal sinus surgery, rhinoplasty, mandibular osteotomy.[1,2,4,6] Endocopic approach of forehead lipoma has been established as a safe, and effective procedure in two series with a total of 12 patients; [2,6] this technique, however, has not become a routine procedure in maxillofacial surgery. The purpose of this article is to advocate the application of endoscopic removal of forehead lipomas. Case report A 28-year-old French white woman presented with two painless masses in the forehead. Except for iodine allergy, her medical history was unremarkable. The patient denied any trauma to the site or any familial occurrence of skin lesions. Physical examination revealed soft, mobile, and nontender masses located on the right side of her forehead measuring 1 X 1, and 1.5 X 2 cm, respectively. None of them were painful and no discolouration of skin surface. Clinically, these findings were consistent with lipomas. She wished to have these masses removed; nevertheless, she was concerned with facial scarring which could be prominent because of her smooth, noncorrugated forehead. (Fig. 1) 5 Prior to surgery, the patient was informed about detail of procedure and possibility of conversion to an open technique. A video system (Karl Storz GmbH & Co. KG, Tuttlingen, Germany) consisting of endoscopic camera (Telecam DX® PAL Video Camera System), flexible and high-intensity light source with cool nature (175-watt Xenon lamp), television monitor, and video recorder was used. A good view was provided by the 4 mm 30° endoscope (18 cm in length) with combined rod lens and light source. The video camera connected to the endoscope eyepiece captured the image that is then projected on a video monitor. During the procedure, the surgical field was seen by viewing a monitor. Magnification aided delineating the subcutaneous structures very well. Several endoscopic instruments, retractors, and periosteal elevators were also used to perform surgical procedure. Even it is possible using local anaesthesia on an outpatient basis, preference should be given to general anaesthesia. Owning to vascularized lushness of facial soft tissues, we advocate an adrenaline infiltration at surgical site in an attempt to reduce intra-operative haemorrhage and allow a hydrodissection effect that is helpful for dissection. To minimize risk of postoperative alopecia, the two 15-mm scalp incisions were created parallel to the long axis of hair follicles. The first one was located in the midline and posterior to the anterior hairline; whereas the other, more laterally, was placed 1 cm behind to the temporal hairline. The incisions were carried down through the galea aponeurotica, and the pockets were linked together in the subaponeurotic space. The first incision was used for the insertion of endoscope and the retractor on which it was mounted. Through the other incision, elevators, forceps, scissors, and curettes were introduced. With an elevator, the subgaleal dissection was performed under endoscopic visualization. At first, masses were not visualized in the dissecting plane because of their location in overlying muscular or subcutaneous layers. The localisation of the masses was estimated by manipulation of the 6 skin externally using the non-dominant hand. Once reaching the tumour location, a dissection of surrounding tissues to free the masses was done with gently digital pressure to the overlying skin for pushing masses downward. (Fig. 2) Complete excision with forceps and long haemostat to remove them piece by piece was relatively easy without additional incisions. (Fig. 3) The resected masses were sent to Department of Pathology for definite diagnosis. Before primary closure with 2 staples at each incision, the cavity was irrigated repeatedly with physiological saline, and the haemostasis was verified. Any drain was unnecessary. The operating time was 30 minutes. A firm dressing with an elastic bandage in a rolling manner from the orbital rim to the incisions was applied for a few days postoperatively. She was discharged from hospitalization at the day of procedure. The patient quickly resumed her daily routine with normal postoperative healing and satisfactory outcome. (Fig. 4) Tumours extracted revealed the result of benign lipomas. There is no evidence of recurrence appeared over the follow-up period to date. Discussion Lipomas are very common lesions which can occur anywhere on the body. Usually, they grow slowly and are expansible before diagnosis.[5] Patients with a lipoma on their face are often disturbed by its appearance and frequently request the surgical removal without scars, particularly in young people and women. Unfortunately, the standard treatment is direct excision, which often leads to conspicuous and unacceptable scars for various reasons: patients with a smooth forehead without many wrinkles, a large mass necessitating a large incision, poor wound healing, predisposition to skin discolouration, and an uneventful healing with hypertrophic scarring, or much more badly, keloid 7 formation, including patients extremely anxious and conscious of any residual forehead scar.[2] Recently, the use of endoscope in craniomaxillofacial surgery has limited the use of wide incisions for exposure. It has been used to visualize the upper face and brow in aesthetic facial surgery.[1,4] A case report by Pozner and their colleagues [8] was the first in which the success of endoscopic application in the treatment of lipoma along the angle of mandible. Since then well other reports has demonstrated the effectiveness of this endoscopically assisted lipoma removal.[2,6,7,9] Its magnification allows the better identification of lesions, or even small nerves, and vessels, [2,6] then it is excellent for the excision of forehead lipomas without conspicuous scarring; this technique minimizes the scalp scarring and blood loss, avoids numbness of forehead, provides a comfortable postoperative recovery, and may shortens length of hospitalization.[2] In contrast with lipomas, dermoid and epidermoid cysts which may be seen in the area of forehead are more fragile (in risk of rupture) and more superficial, as well as neccessitate removing the cutaneous pore. When they rupture, the inflammatory reaction is usually seen. Thus it is more time-consuming and technically demanding in such cases.[2,6] To our opinion, it is so advisable that the preoperative evaluation and differential diagnosis necessitate for both treatment plan and patient inform. The differential diagnosis of forehead masses includes lipoma, osteoma, dermoid cyst, epidermoid cyst, haemangioma, and a number of malignancies. Lipoma is usually soft, and mobile; the procedure can be converted to a direct approach without difficulty in cases of the extensive lesions or suspicion of malignancy. In addition, incision can be enlarged to accommodate pulling masses out.[2] Projection from the television monitor can be recordable for medical students’ and trainees’ study in surgical anatomy. By our experience, we use 4.0 mm-diameter rigid endoscopes because of its capability of tissue retraction providing the better operative field, 8 compared with the flexible ones often used in exploratory surgery via the natural openings, such as antral osteum, rectum or ductal orifice. We, moreover, find we can be more precious when the high intensity light with cool nature from the Xenon lamp is introduced to use in our procedures adjunctive to the endoscope instead of the old fashion; this brings us the better quality of light. Regarding the dissection plane for approaching the forehead masses, subgaleal plane which is superficial to the deep temporal fascia is preferred. This dissection will offer a wider operative field, a nearly direct approach to masses, as well as prevent injury of the temporal branch of facial nerve.[6] Nonetheless, endoscopic surgery possess several limitations, such as the training and learning curve necessary to achieve optimal results, the initial increased operation time, the use of new instrumentation, as well as the overall investment in the endoscopic instruments. The endoscopic approach to forehead masses carries the same risk of damage to frontal branch of facial nerve and/or supraorbital nerve due to requirement of dissection in the frontotemporal area. However, the incidence of frontal nerve weakness and persistent dysaesthesias in endoscopic forehead rejuvenation has been reported approximately 1.8, and 2.3 per cents, respectively. This may be due to good illumination and magnification; nerve fibres are clearly identified and preserved.[2,4,6] A simple landmark for identification of supraorbital and supratrochlear nerves was explained by Cuzalina and Holmes.[3] It was found that all nerves coursed 2 mm or less from a vertical line constructed tangential to medial limbus at the supraorbital rim. Greater care should be taken when dissection in this area will be performed. On concern in a learning curve, it is steep after the first five or ten procedures, and general laparoscopic equipments can be adapted in this kind of surgery.[2] Besides, as the endoscopic surgery becomes increasingly available, its drawbacks will be solved. 9 Now, during the peak of interest in minimally invasive surgery with limited scars using endoscope is the time to highlight this time-sparing, safe, and effective approach. The endoscope is a useful adjunct not only for diagnosis but also for resection of forehead lesions. Application of endoscope provides advantages over the conventional direct excision and avoids a handful of undesirable sequelae, especially a more aesthetically pleasing result. Careful examination should be carried out to exclude the malignant lesions and we recommend careful selection based on the indications described. References 1. CHIU ES, BAKER DC. Endoscopic brow lift: a retrospective review of 628 consecutive cases over 5 years. Plast Reconstr Surg 2003; 112: 628-633. 2. CRONIN ED, RUIZ-RAZURA A, LIVINGSTONE CK, TIMOTHY KATZEN J. Endoscopic approach for the resection of forehead masses. Plast Reconstr Surg 2000; 105: 2459-2463. 3. CUZALINA AL, HOLMES JD. A simple and reliable landmark for identification of the supraorbital nerve in surgery of the forehead: an in vivo anatomical study. J Oral Maxillfac Surg 2005; 63: 25-27. 4. DE CORDIER BC, DE LA TORRE JI, AL-HAKEEM MS, ROSENBERG LZ, GARDNER PM, COSTA-FERREIRA A, et al. Endoscopic forehead lift: review of technique, cases, and complications. Plast Reconstr Surg 2002; 110: 1558-1568. 5. DANIELSON PA. Soft Tissue Cysts and Benign Neoplasms. In: FONSECA RJ, ed.: Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. Vol. 5. Surgical Pathology. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders, 2000: 137-138. 10 6. LIN SD, LEE SS, CHANG KP, LIN TM, LU DK, TSAI CC. Endoscopic excision of benign tumors in the forehead and brow. Ann Plast Surg 2001; 46: 1-4. 7. PAIGE KT, EAVES EF III, WOOD RJ. Endoscopically assisted plastic surgical procedures in the pediatric patient. J Craniofac Surg 1997; 8: 164-167. 8. POZNER JN, CANICK MI, RAMIREZ OM. Endoscopically assisted lipoma removal. Plast Reconstr Surg 1996; 98: 376-377. 9. SAKAI Y, OKAZAKI M, KOBAYASHI S, OHMORI K. Endoscopic excision of large capsulated lipomas. Br J Plast Surg 1996; 49: 228-232. Captions to illustrations Fig.1: Preoperative photograph showing two forehead lipomas. Fig.2: Endocopic view during freeing masses. R: retractor, L: lipoma, S: scissors. Fig.3: Endocopic view during removing masses. R: retractor, L: lipoma, F: forceps. Fig.4: Postoperative photograph at 1-month follow-up. 11 Fig.1 12 Fig. 2 13 Fig. 3 14 Fig. 4