FREEING BLOCKED PAIN AND FEAR - Kelley

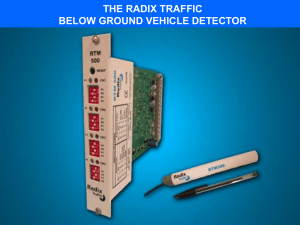

advertisement