Early Child Care and Children`s Development in the Primary Grade:

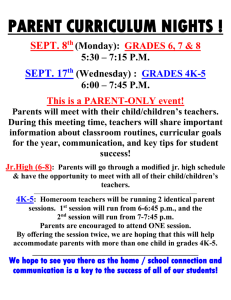

advertisement