Rimm-Kauffman and Hench, Responsive Classroom

advertisement

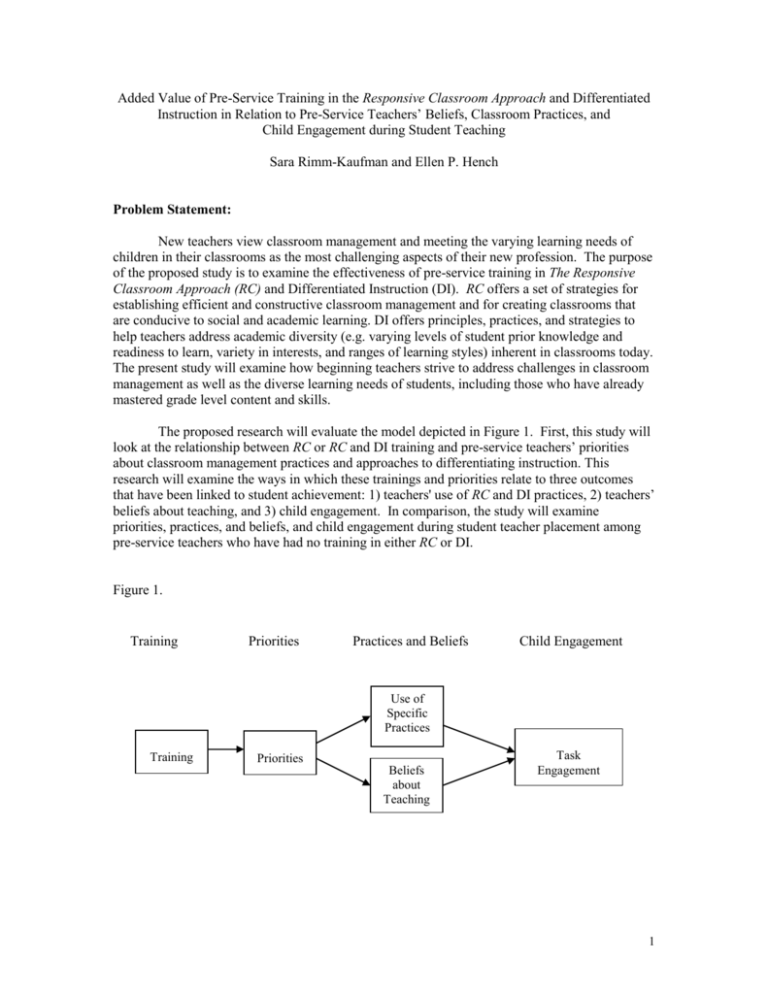

Added Value of Pre-Service Training in the Responsive Classroom Approach and Differentiated Instruction in Relation to Pre-Service Teachers’ Beliefs, Classroom Practices, and Child Engagement during Student Teaching Sara Rimm-Kaufman and Ellen P. Hench Problem Statement: New teachers view classroom management and meeting the varying learning needs of children in their classrooms as the most challenging aspects of their new profession. The purpose of the proposed study is to examine the effectiveness of pre-service training in The Responsive Classroom Approach (RC) and Differentiated Instruction (DI). RC offers a set of strategies for establishing efficient and constructive classroom management and for creating classrooms that are conducive to social and academic learning. DI offers principles, practices, and strategies to help teachers address academic diversity (e.g. varying levels of student prior knowledge and readiness to learn, variety in interests, and ranges of learning styles) inherent in classrooms today. The present study will examine how beginning teachers strive to address challenges in classroom management as well as the diverse learning needs of students, including those who have already mastered grade level content and skills. The proposed research will evaluate the model depicted in Figure 1. First, this study will look at the relationship between RC or RC and DI training and pre-service teachers’ priorities about classroom management practices and approaches to differentiating instruction. This research will examine the ways in which these trainings and priorities relate to three outcomes that have been linked to student achievement: 1) teachers' use of RC and DI practices, 2) teachers’ beliefs about teaching, and 3) child engagement. In comparison, the study will examine priorities, practices, and beliefs, and child engagement during student teacher placement among pre-service teachers who have had no training in either RC or DI. Figure 1. Training Priorities Practices and Beliefs Child Engagement Use of Specific Practices Training Priorities Beliefs about Teaching Task Engagement 1 Related Work: The Responsive Classroom Approach provides teachers with a set of practices that enhances classroom climate, emphasizes proactive versus reactive discipline procedures, and uses social relationships and interactions in ways that contribute to learning. Preliminary research on RC points to its effectiveness in reducing behavior problems and enhancing children’s academic achievement (Elliott, 1993). Current research, conducted here in the Curry School of Education, suggests that teachers who use more RC practices report a shift in priorities about classroom practices and discipline, greater disciplinary and instructional efficacy, and more positive attitudes toward teaching (Rimm-Kaufman & Sawyer, 2004; Rimm-Kaufman, Storm, Sawyer, Pianta, & La Paro, in preparation). To date, there has been no research examining the effectiveness of RC practices in pre-service teachers. Differentiated Instruction offers teachers a philosophy supported with instructional strategies to address the academic learning needs of each student in a classroom – from struggling learner to a student who has already mastered the grade-level content (Tomlinson, 2001, 1999). Research in Differentiated Instruction among practicing teachers has shown that for them to successfully implement DI, oftentimes, they must make a paradigm shift in their visions for how to teach in a specific content area or to teach at a specific grade level. To effectively differentiate instruction, teachers used to teaching within content and grade level parameters must seek opportunities to assess the needs of all of their students and then plan appropriately challenging and respectful lessons to help each child grow academically (Brighton & Hertberg, 2003). Research of training in Differentiated Instruction for pre-service teachers is limited. A study at UVA in collaboration with three other universities indicated that a one-day training with coaching during student teaching was largely not effective in shaping student teaching priorities and behaviors (Tomlinson, et al., 1993). Four bodies of literature frame the current study. The first body of literature introduces and examines the effectiveness of programs designed to enhance children’s social and emotional experience in school. Typically, these programs exemplify a relational approach to education. Programs have been developed to enhance the classroom environment (Zins, Weissberg, Wang & Walberg, 2004; Battistich, Solomon, Kim, Watson, & Schaps, 1995), reduce aggression among students (Kellam, Ling, Merisca, Brown, & Ialongo, 1998), prevent mental disorders (Greenberg, Domitrovich, & Bumbarger, 1999), and reduce likelihood of substance abuse and school failure (Zins, et al., 2004). Research on such programs finds them beneficial to children’s social and academic outcomes if they are implemented with integrity (e.g., Abbott, O’Donnell, Hawkins, Hill, Kosterman, & Catalano, 1998; Battistich, Solomon, Watson, & Schaps, 1997; Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 1999). The goals and scope of RC resemble these programs. The second body of relevant literature establishes the basis for differentiating instruction to meet the varied learning needs of students in a typical classroom. Tomlinson, (2003) contends that all students – an increasingly diverse group in our schools and society – must be accommodated in school with curriculum and instruction that is appropriately matched to their individual learning needs. Readiness to learn, personal interest, and learning styles all work together to influence a student’s ability to achieve and grow academically (Tomlinson, 1999; Bransford, Brown, & Cocking, 2000; Jensen, 1998). Teachers who implement strategies to identify and address individual learning differences impact academic growth through increased student motivation, student engagement, and academic achievement (Tomlinson, 2001; Zins, Weissberg, Wang, & Walberg, 2004; Brighton & Hertberg, 2003; Bransford, et al., 2000). The third body of relevant literature describes the relationship between teachers’ beliefs and priorities and classroom practices. Teachers vary in their beliefs and priorities about 2 teaching; such beliefs have been shown to be associated with teacher practices, and more tenuously, children’s social behavior and academic performance (Calderhead, 1996). For example, Cheng (1996) reports that teachers with greater commitment to teaching are more likely to have students who report positive attitudes toward peers, schools, and learning. Solomon, Battistich, & Hom (1996) report an association between teachers’ trust toward students and children’s observed active engagement in the classroom. Midgley, Feldlaufer, & Eccles (1989) describe an association between teachers’ self-efficacy and the self-efficacy of their students. This research is framed by a fourth body of literature linking classroom social processes and children’s behavior. One tension that emerges prominently in this research is the challenge that teachers face in balancing academic rigor with emotional support for learning. Brophy & Evertson (1976) describe that teachers concerned only with their personal relationships with children and concerned rarely with academic objectives produced the lowest levels of achievement. One barrier teachers describe in implementing emotionally-supportive practices is the time it takes to create these experiences in the classroom (Charney, 1991), thus competing with time for instruction. Ideal emotionally-supportive practice emphasizes the social aspects of the classroom without diminishing the importance of academic objectives (Battistich, Solomon, Watson, & Schaps, 1997; NEFC, 1997). Encouraging recent analyses of data on programs focusing on Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) provide evidence of the positive connections between social/emotional classroom support and academic achievement (Zins, Weissberg, Wang, & Walberg, 2004). Studies, however, are limited and more research is needed to examine specific components of the interventions that contribute to academic achievement. These four bodies of research provide insight into the contribution of relational approaches to teachers’ beliefs, priorities, and classroom practices. They also provide insight into the teacher’s challenge for meeting the learning needs of diverse students. The present study will contribute to these bodies of research by examining the effectiveness of intervening early in a teacher’s career, while the pre-service teacher is still in university training. The goals of this study are two-fold: 1) to provide pre-service teachers with a set of priorities and practices that organize and enhance their classroom management and instructional approaches and 2) to provide preservice teachers with a set of skills to create classroom environments that not only respect the social and emotional needs of children, but also benefit all children’s learning, giving consideration to their varying readiness levels, interests, and learning styles (Tomlinson, 1999). Teachers make frequent decisions in their classrooms - about how to manage the classrooms and how to address individual learner needs. Their beliefs about students and their beliefs about their role as teacher permeate those decisions. This study examines the relationship of these beliefs to student teachers’ classroom behaviors in the context of interventions designed to modify both. Questions and Hypotheses: We will ask the following three questions: 1. Does training in RC or RC and DI result in a shift in priorities in pre-service elementary school teachers? We hypothesize that pre-service teachers will show a change in their priorities after RC or RC and DI training. After RC training, we expect pre-service teachers will hold priorities that are more similar to those of RC exemplars as measured by the Teacher Belief Q-Sort (TBQ; Rimm-Kaufman, et al, in preparation). For those pre-service teachers who have also had DI training we expect they will hold priorities that are congruent with the philosophy and strategies of Differentiated Instruction (Tomlinson, 2001, 1999). 3 2. How does a shift in priorities relate to pre-service teachers’ use of RC or RC and DI practices and beliefs about teaching during student teaching? We expect that pre-service teachers who implement RC or RC and DI practices during their student teaching (as measured by self-report, interviews, observations, and two, two-hour tapes of their teaching) will feel more efficacious and hold more positive feelings about teaching as a potential career than those who do not implement these practices. 3. Does effective use of RC or RC and DI practices and positive beliefs about teaching (during the student teaching experience) relate to children’s classroom behavior (task engagement)? We expect that pre-service teachers who use RC or RC and DI practices will have created an expectation for certain behaviors from their students and will be more closely addressing the diverse learning needs of their students. We expect that pre-service teachers who use RC or RC and DI with integrity will be more effective at maintaining children’s attention and keeping children “on task” during their student teaching. Procedure for Collecting Data: Participants Six elementary pre-service teachers will be recruited from the UVA PGMT and BAMT teacher education programs in Spring 2004. Students will have identified themselves as “definitely planning to teach” following graduation and will be student teaching in Fall 2004. Four of the pre-service teachers will participate in RC training that will be offered at the Curry School of Education during the week of May 17-21. Of the four, two will also participate in the first week of the Summer Institute for Academic Diversity during the week of July 11-16 for training in Differentiated Instruction. The four pre-service teachers with summer training in Responsive Classroom or Responsive Classroom and Differentiated Instruction will be observed, interviewed, and videotaped during their Fall 2004 student teaching placement. Two additional pre-service teachers who have received no additional training to the UVA teacher education program will also be recruited to be interviewed, observed, and videotaped during their Fall 2004 student teaching. Methods In early May 2004, all six of the pre-service teachers participating in the study will complete the Teacher Belief Q-Sort, as well as several other questionnaires on teacher beliefs and priorities. They will also be interviewed individually to explore their beliefs and priorities about teaching. Each interview with a pre-service teacher will be audio-taped and transcribed. During the week of May 17-21, four of the pre-service teachers will participate in RC training at the Curry School of Education. The training will be conducted by a trainer from the Northeast Foundation for Children, the developer of the Responsive Classroom Approach. Following the training, the pre-service teachers will complete the Teacher Beliefs Q-Sort and be interviewed for a second time about their beliefs and priorities. Two of the four pre-service teachers who have received the RC training will also participate in training in Differentiated Instruction through the UVA Summer Institute for Academic Diversity during the week of July 12-16. Following the DI training those pre-service teachers will have a third interview about their beliefs and priorities about teaching. 4 In the Fall, 2004, all six pre-service teachers will be interviewed and observed throughout their student teaching placements, and they will be video-recorded twice for two hour sessions as the primary teacher in the classroom. The tapes will serve up to three purposes: 1) to collect data on each pre-service teacher and her students, 2) to provide material for coaching between the preservice teacher and an RC trainer for those pre-service teachers trained in RC, and 3) to provide opportunity for coaching between the pre-service teacher and the DI instructor for those preservice teachers who have also been trained in DI. Each of the Clinical Instructors for the six pre-service teachers will be interviewed three times during the student teaching semester for her perceptions and observations of the student teacher’s experiences in the classroom. Each Clinical Instructor will complete the Teacher Beliefs Q-Sort prior to working with the student teacher. Analyses: This study employs a qualitative research methodology and interviews and observations will be coded and analyzed using the grounded theory method of data analysis (Strauss & Corbin, 1990). The purpose of grounded theory analysis is to explore and reduce data, and develop theory about a specific phenomenon, in this case pre-service teacher beliefs and practice priorities. Observation and interview data will be analyzed to develop theory about how additional pre-service teacher training in a specific classroom management strategy, the Responsive Classroom Approach (RC), or the combination of RC training and training in Differentiating Instruction (DI) may provide insight into how beginning teachers view their abilities to create classrooms conducive to social and academic learning and to address the diversity in academic learning needs among a group of children within an age-based classroom. Spearman correlation coefficients will also be computed for each pre-service teacher on the Teacher Beliefs Q-Sort (TBQ) to examine changes in classroom management and practice priorities, and beliefs about children. These Q-sort analyses will follow those procedures recommended by Block (1961). Pre-service teacher Q-Sort outcomes will be compared to criterion RC and DI exemplars. Descriptive approaches will be used to analyze the pre-service teacher questionnaires as additional information to corroborate the qualitative findings. Child engagement will be evaluated in each student teacher’s videotapes using McWilliam’s Engagement Check II procedure (de Kruif et al., 2000). Engagement, defined as attention to or active participation in classroom activities, is determined as the percentage of children involved during a particular learning activity and for specific time intervals. Expected Product: Findings will be reported to the TNE Initiative through the dissertation of Ellen P. Hench. Further, the findings will provide pilot work necessary to substantiate further internal funding and/or support an application for external funds for augmentation to the UVA teacher preparation program through training in the Responsive Classroom Approach and Differentiated Instruction. These findings will be relevant to four groups: 1) researchers interested in relational approaches to schooling and their impact on academic achievement, 2) the Northeast Foundation for Children, developers of RC, 3) researchers interested in applying Differentiated Instruction to meet the diverse academic needs of children and its impact on academic achievement, and 4) instructors of the UVA teacher training program. As a side product, this project will initiate a discussion of integrating RC principles and practices into already existing courses of the teacher education program at Curry. The RC 5 training session in May will include a special two-hour orientation session for faculty to spur this conversation. Personnel: Dr. Sara Rimm-Kaufman and Ellen P. Hench, doctoral student, will be the co-principal investigators of this study. Iris Chiu, doctoral student, will assist in project management and analysis of data. 6 References Abbott, R. D., O’Donnell, J., Hawkins, J. D., Hill, K. G., Kosterman, R., & Catalano, R. F. (1998). Changing teaching practices to promote achievement and bonding to school. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 68(4), 542-552. Battistich, V., Solomon, D., Kim, D., Watson, M., & Schaps, E. (1995). Schools as communities, poverty levels of student populations, and students’ attitudes, motives, and performance: A multi-level analysis. American Educational Research Journal, 32(3), 627-658. Battistich, V., Solomon, D., Watson, M., & Schaps, E. (1997). Caring school communities. Educational Psychologists, 32(3), 137-151. Block, J. (1961). The Q-sort method in personality assessment and psychiatric research. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas Bransford, J.D., Brown, A.L., & Cocking, R.R. (Eds.). (2000). How people learn: Brain, mind, experience, and school. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press. Brighton, C. & Hertberg H. (2003). Differentiating differentiation in response to teachers’ readiness. Paper presented at the National Association for Gifted Children Conference. Indianapolis, IN. Brophy, J., & Evertson, C. (1978). Context variables in teaching. Educational Psychologist, 12, 310-316. Calderhead, J. (1996). Teachers, beliefs, and knowledge. In D. C. Berliner & R. C. Calfee (Eds.), Handbook of educational psychology, (pp. 709-725). New York: Simon & Schuster. Charney, R. (1991). Teaching children to care: Management in the Responsive Classroom. Greenfield, MA: Northeast Foundation for Children. Cheng, Y. C. (1996). Relation between teachers’ professionalism and job attitudes, educational outcomes, and organizational factors. Journal of Educational Research, 89(3), 163-171. Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group (1999). Initial impact of the Fast Track Prevention Trial for conduct problems: II. Classroom effects. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 67(5), 648-657. de Kruif, R. E. L., McWilliam, R. A., Ridley, S. M., & Wakely, M. B. (2000). Classification of teachers’ interaction behaviors in early childhood classroom. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 15(2). Elliott, S. N. (1993). Caring to learn: A report on the positive impact of a social curriculum. Greenfield, MA: Northeast Foundation for Children. Greenberg, M. T, Domitrovich, C., & Bumbarger, B. (2001). The prevention of mental disorders in school aged children: Current state of the field. Prevention and Treatment, 4. Jensen, E. (1998). Teaching with the brain in mind. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. 7 Kellam, S. G., Ling, X., Merisca, R., Brown, C. H., & Ialongo, N. (1998). The effect of the level of aggression in the first grade classroom on the course and malleability of aggressive behavior into middle school. Development and Psychopathology, 19, 165-185. Mayer, J. & Cobb, C. (2000). Educational policy on emotional intelligence: Does it make sense? Educational Psychology Review, 12(2), 163-183. Midgley, C., Feldlaufer, H., & Eccles, J. S. (1989). Change in teacher efficacy and student selfand task-related beliefs in mathematics during the transition to junior high school. Journal of Educational Psychology, 81(2), 247-258. Northeast Foundation for Children, (1997). Guidelines for the Responsive Classroom. Greenfield, MA: Northeast Foundation for Children Rimm-Kaufman, S. E., & Sawyer, B. E. (2004). Primary grade teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs, attitudes toward teaching, and discipline and teaching practice priorities in relation to the Responsive Classroom Approach. The Elementary School Journal, 104(4). Rimm-Kaufman, S. E., Storm, M., Sawyer, B. E., La Paro, K., Pianta, R. C. (in preparation). A Q-sort method for measuring teachers’ practices, priorities, and beliefs. Solomon, D., Battistich, V., & Hom, A. (1996). Teachers’ beliefs and practices in schools serving communities that differ in socioeconomic level. The Journal of Experimental Education, 64(4), 327-347. Strauss, A. & Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Newbury Park, CA: SAGE. Tomlinson, C. A., Callahan, C. M., Moon, T. R., Tomchin, E. M., Landrum, M., Imbeau, M., Hunsaker, S. L., & Eiss, N. (1993). Pre-service teacher preparation in meeting the needs of gifted and other academically diverse students. Charlottesville, VA: National Research Council for the Gifted and Talented. Tomlinson, C. A. (1999). The differentiated classroom: Responding to the needs of all learners. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. Tomlinson, C. A. (2001). How to differentiate instruction in mixed-ability classrooms (2nd ed.). Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. Tomlinson, C.A. (2003). Fulfilling the promise of the differentiated classroom: Strategies and tools for responsive teaching. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. Zins, J. E., Weissberg, R. P., Wang, M. E., & Walberg, H. J., (Eds.).(2004). Building academic success on social and emotional learning: What does the research say? New York, NY: Teachers College Press. 8