Take Action: Involve Parents, Improve Achievement

advertisement

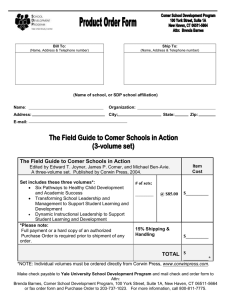

Take Action: Involve Parents, Improve Achievement In his book What Works in Schools: Translating Research into Action, Robert Marzano shows that 35 years of research reveal that parent and community involvement has an even greater impact on student achievement than orderly schools or teacher professionalism. Robert J. Marzano The importance of parent involvement on student achievement is explicit in the research, whereas the importance of community involvement is more implicit. Three aspects of parent and community involvement are important to student achievement: mechanisms for communication, involvement in the day-to-day running of the school, and the use of governance structures. I've recommended three action steps to address these three aspects and to promote effective parent and community involvement in schools. Action Step 1. Establish vehicles for communication between schools and parents and the community. Communication does not occur automatically. Rather, specific vehicles must be established to facilitate the flow of information to and from the school. Beth Antunez (2000) offers the stated policies of the San Francisco Unified School District (SFUSD) as a noteworthy example. As described by Antunez, SFUSD established the policy that each pre-school through high school must develop a long-range plan to enhance communication between the school site and parents. Suggestions include All school communications should be issued in the major languages of the school's linguistically diverse students. All public meetings should be translated from English into the major languages of the linguistically diverse students. Public meetings should be conducted on a regular basis in the languages of the parents and translated into English. One of the more important aspects of the SFUSD initiative is that it doesn't stop at simply listing ways that a school might enhance the flow of information. It also addresses perhaps the most important feature of this communication—making information easily and readily available. Specific ways for schools to establish effective lines of communication, particularly with parents, have been in place for some time and include phone calls, the Internet, home visits, and parent-teacher conferences. Studies indicate that phone calls to parents by the principal are particularly effective in decreasing truancy and absenteeism (Parker & McCoy, 1977; Sheats & Dunkleberger, 1979). The major problem with phone calls is that they are time consuming and labor intensive (National Education Association, 1982). Recorded telephone messages have been used effectively to inform parents about school activities (Bittle, 1975). In the last decade, the Internet has greatly expanded the options for parent and school interaction. Some schools provide weekly or even daily access to information. Indeed, schools now commonly establish their own Web sites to provide information to parents and the community in general. Home visits are common but they are labor intensive and have shown inconsistent results in changing student behavior or enhancing academic achievement (Tangri & Moles, 1987). Evidence exists that home visitations bring long-term benefits (Olmsted, 1983). Finally, the time-honored parent-teacher conference is used widely. Protocols for effective parent-teacher conferences commonly include suggestions regarding general teacher dispositions such as warmth, attentiveness, and responsiveness (Rotter & Robinson, 1982) and suggestions on handling parents' resistance to negative information (Losen & Diament, 1978). Action Step 2. Establish multiple ways for parents and community to be involved in the day-to-day running of the school. Researchers indicate that nothing creates more of a sense of ownership than being involved in day-to-day school activities (Antunez, 2000; Center for Community Education, 1989; Onikama, Hammond, & Koki, 1998; Parent Teacher Association, 1997). Using volunteers is the most common vehicle for this type of involvement (Tangri & Moles, 1987) One study estimates that volunteers are used in some capacity in 79 percent of the public school districts in the country (Thomas, n.d.). Volunteers are used in a wide variety of ways, such as classroom aides, hallway, lunchroom, and playground monitors, office clerical assistants, and guest lecturers and presenters. According to Tangri and Moles (1987), factors that appear critical to the success of volunteer programs include appropriate recruiting and training techniques, orientation workshops, staff training on appropriate volunteer use, and consideration of legal and financial aspects of volunteer programs. Some volunteer programs are specifically designed to involve businesses. Sometimes referred to as "adopt-a-school" models, they allow the sponsoring business to "take students on tours of the business, let them try out equipment, give demonstrations of new technology, and develop minicourses" (Tangri & Moles, 1987, p. 541). Specific programs designed to involve the business community in school operations include The Community as a Classroom, The Community as Textbook, and Learning from Volunteering and Other Roles (Gonder, 1981). Action Step 3. Establish governance vehicles that allow for the involvement of parents and community members. Governance structures are the most formal vehicles for parent and community involvement. James Comer's work (1984, 1988) is the most recognized and well researched on this issue. Comer's School Development Program (SDP) was first implemented in two elementary schools in New Haven, Connecticut and now operates in more than 700 schools (American Institute for Research, 1999). Central to Comer's model are three "mechanisms"—the School Planning and Management Team, the Student and Staff Support Team, and the Parent Team. All deal with school governance; two involve parents or community members. Led by the principal, the School Planning and Management Team is composed of approximately a dozen teachers, parents, professional support staff (e.g., school psychologists, social workers), and paraprofessional staff (e.g., secretaries, janitors, classroom aides). The purposes of this team include establishing policies that affect the curriculum, the overall school environment, and staff development; carrying out school planning activities, implementing programs, and evaluating the effectiveness of schoolwide initiatives; coordinating the activities of the various groups functioning in the school; and working with parents and the community to establish a calendar for social and informational activities. The Student and Staff Support Team does not explicitly involve parents and community members but is composed of teachers, school psychologists, social workers, special education teachers, counselors, and other support staff. The team provides input to the School Planning and Management Team on learning and development needs and teacher efforts to work with students who are having behavior or learning problems. By definition, the Parent Team most directly addresses the involvement of parents. As the American Institute for Research (1999) describes it: There are different levels of participation, so parents can choose how involved they wish to be. All parents are encouraged to participate in several school-sponsored activities each year, such as a field trip to a museum. These activities allow parents to get to know members of the school staff, so they feel more comfortable with the school. Parents who wish to be involved more directly are encouraged to participate as classroom assistants, tutors, or aides. Finally, parents who are committed to being highly involved can participate as members of the School Planning and Management Team. (pp. 111–112) Of course, many types of governance structures exist that involve parents and community members other than those within Comer's model. For example, the School/Community-Based Management (SCBM) program (Onikama et al., 1998) uses a more site-based management approach. Like Comer's SDP, SCBM utilizes specific governance structures that involve parents and community. According to Onikama and colleagues: An evaluation of SCBM by the Far West laboratory (now WestEd) revealed that SCBM has a significant impact on school decision-making practices. It was also found that decision-making and school-community connections are strongly linked. (p. 16) References American Institute for Research. (1999). An educator's guide to schoolwide reform. Arlington: VA: Educational Research Service. Antunez, B. (2000). When everybody is involved: Parents and communities in school reform. National Center for Bilingual Education [Online]. Retrieved January 6, 2006, from http://www.ncela.gwu.edu/pubs/tasynthesis/framing/6parents.htm Bittle, R. G. (1975). Improving parent-teacher communication through recorded telephone messages. Journal of Educational Research 69(3), 87–95. Center for Community Education. (1989). A model for rural schools to involve parents in the education of their children. Bozeman, MT: Montana State University. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED329395) Comer, J. P. (1984). Home-school relationships as they affect the academic success of children. Education and Urban Society, 16(3), 323–337. Comer, J. P. (1988). Educating poor minority children. Scientific American, 259(5), 42–48. Gonder, P. O. (1981). Exchange school and community resources. In D. Davies (Ed.), Communities and their schools. New York: McGraw-Hill. Losen, S. M., & Diament, B. (1978). Parent conferences in the schools. Boston: Allyn & Bacon. National Education Association. (1982). Productive relationships: Parent-school-teacher. Washington, DC: Author. Olmsted, P. P. (1983). Long-term effects of Parent Education Follow Through program participation. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, School of Education. Onikama, D. L., Hammond, O. W., & Koki, S. (1998). Family involvement in education: A synthesis of research for Pacific educators. Honolulu, HI: Pacific Regional Educational Laboratory. Parent Teacher Association. (1997). PTA Guide to the National Standards for Parent/Family Involvement Programs [Online]. Available: http://www.pta.org/programs/stnrdgd.htm [1998, April]. Parker, F. C., & McCoy, J. F. (1977). School-based intervention for the modification of excessive absenteeism. Psychology in the Schools, 14, 84–88. Rotter, J. C., & Robinson, E. H., III. (1982). Parent-teacher conferencing. Washington, DC: National Education Association. Sheats, D., & Dunkleberger, G. E. (1979). A determination of the principal's effect in schoolinitiated home contacts concerning attendance of elementary school students. Journal of Educational Research, 72(6), 310–312. Tangri, S., & Moles, O. (1987). Parents and the community. In V. Richardson-Koehler (Ed.), Educators' handbook: A research perspective (2nd ed., pp. 519–550). New York: Longman. Thomas, M. D. (n.d). Volunteerism in public education. Salt Lake City, UT: Salt Lake School District. Source: From What Works in Schools: Translating Research into Action (pp. 49–52), by R. J. Marzano, 2003, Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. Copyright 2003 by ASCD.