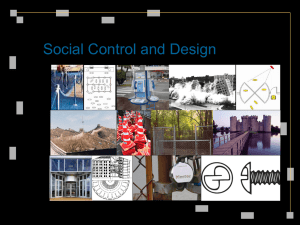

Background information on SSI surveillance

advertisement