Press Here To Change from HTML to Word Document

advertisement

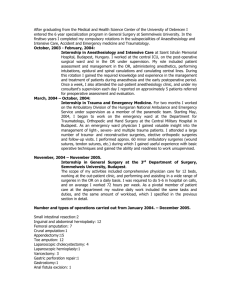

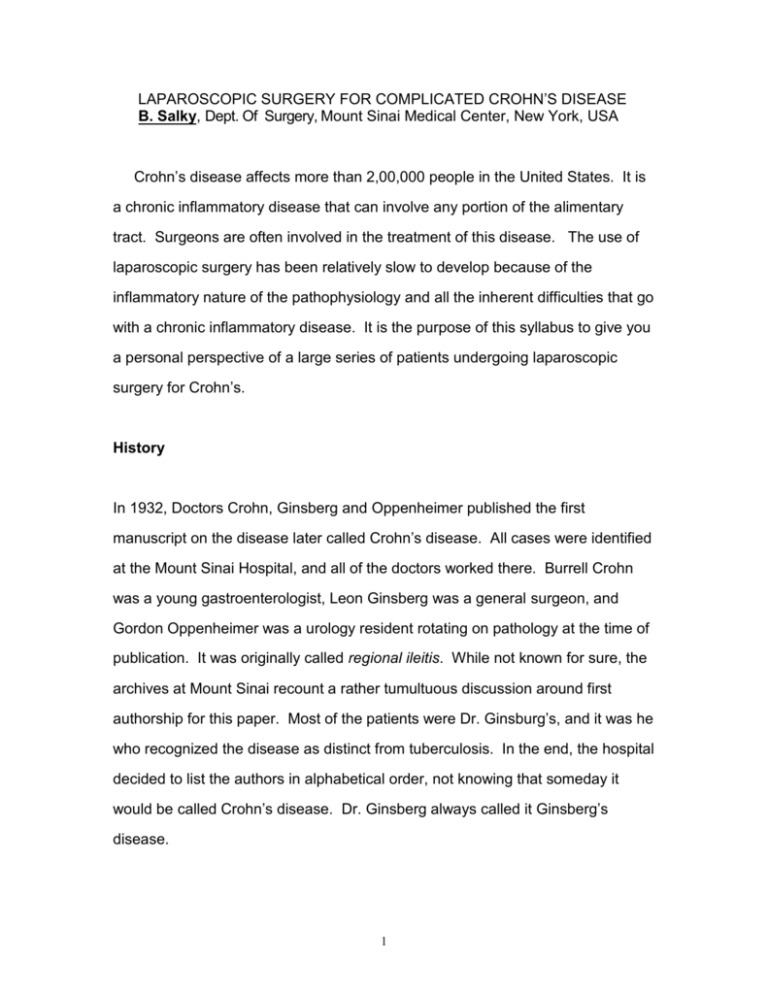

LAPAROSCOPIC SURGERY FOR COMPLICATED CROHN’S DISEASE B. Salky, Dept. Of Surgery, Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York, USA Crohn’s disease affects more than 2,00,000 people in the United States. It is a chronic inflammatory disease that can involve any portion of the alimentary tract. Surgeons are often involved in the treatment of this disease. The use of laparoscopic surgery has been relatively slow to develop because of the inflammatory nature of the pathophysiology and all the inherent difficulties that go with a chronic inflammatory disease. It is the purpose of this syllabus to give you a personal perspective of a large series of patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery for Crohn’s. History In 1932, Doctors Crohn, Ginsberg and Oppenheimer published the first manuscript on the disease later called Crohn’s disease. All cases were identified at the Mount Sinai Hospital, and all of the doctors worked there. Burrell Crohn was a young gastroenterologist, Leon Ginsberg was a general surgeon, and Gordon Oppenheimer was a urology resident rotating on pathology at the time of publication. It was originally called regional ileitis. While not known for sure, the archives at Mount Sinai recount a rather tumultuous discussion around first authorship for this paper. Most of the patients were Dr. Ginsburg’s, and it was he who recognized the disease as distinct from tuberculosis. In the end, the hospital decided to list the authors in alphabetical order, not knowing that someday it would be called Crohn’s disease. Dr. Ginsberg always called it Ginsberg’s disease. 1 Introduction Surgeons operate for the complications of the disease. The effects of the pathophysiology of transmural inflammation explain these complications. The etiology of this disease is unknown at present. The most common indications for surgery are obstruction, fistulization and abscess formation. Free perforation and gastrointestinal bleeding are rare indications. The transmural inflammatory process also explains the difficulty in operating on these patients. The combination of transmural inflammation and the medications used to treat it (immunosuppressives) can make for difficult dissections. Recurrence after resection is also common. Therefore, re-operative surgery is also relatively common. These are the reasons general surgeons have been slow to embrace laparoscopic surgery and Crohn’s disease. However, as experience has accumulated, more patients with both straightforward and complicated disease have undergone laparoscopic surgery. The benefits of minimally invasive surgery have been realized in this group of patients as well. Surgical Approach The decision to use open or minimally invasive surgery for Crohn’s disease is dependent upon the experience of the surgeon and the pathology found at the time of surgery. As surgery for Crohn’s disease can encompass a variety of pathologies and surgical procedures, the ability to complete a case laparoscopically will vary tremendously. The other significant variable in Crohn’s disease is that previous resection is common, and it is not rare for some patients to have two or more previous open surgeries. The combination of previous 2 surgery and significant inflammatory disease (phlegmon, abscess, fistula, or perforation) will affect the ability of the surgeon to complete the procedure laparoscopically. Whether the surgery is performed open or laparoscopically, the basic tenets of surgery are the same. Conservation of bowel is the primary goal in surgery for Crohn’s disease. The amount of bowel resected is based on gross disease. It is not based on microscopic involvement. As any portion of the bowel can be involved with disease, tit is also important to run the bowel from stomach to rectum. This can be accomplished in the laparoscopic arena as in open surgery. A systematic approach to visualization must be adopted, and twohanded technique with atraumatic bowel instrumentation is required. As with all inflammatory bowel disease surgery, incisions in the right lower quadrant should be avoided, as it is a potential site of an ileostomy in the future. This is much less an issue with laparoscopic surgery compared to open. In this authors’ experience, all Crohn’s cases are a t least started laparoscopically. Conversion to open is based on local factors, which can preclude the sage performance of the laparoscopic procedure. Ureteral stents are not employed in either laparoscopic or open surgery. However, the ureters are identified. Failure to identify the ureters is a reason for conversion to open surgery. In the authors’ experience of more than 250 laparoscopic resections for Crohn’s disease, conversion to open for failure to identify the ureters has not occurred. The main reason for conversion has been a thick mesentery that did not allow safe division with any laparoscopic instrument. In each of the converted cases, the disease process had been in place more than 20 years. Previous surgery in and of itself has not been a reason to convert to open. In the past, Crohn’s patients traditionally have had a relatively high incidence of wound complications including infection and hernia. In some series, it is reported to be as high as 15%. This is thought to be secondary to the transmural nature of the disease 3 process, and the common use of immunosuprressive medication in the treatment of the disease. The wound complications have all but disappeared in the laparoscopic group. In the authors’ experience, the incidence of wound complications is 2 per cent. It is a major advantage of laparoscopic resection compared to open surgery for Crohn’s disease. Gastro-duodenal Crohn’s disease deserves special mention as resection is not involved with this aspect of the disease, and therefore, an assisted incision is not made. Laparoscopic gastrojejunostomy negates nearly all the potential wound complications of open gastrojejunostomy, and length of stay in hospital has been shortened dramatically for this group of patients. Patient Selection and Evaluation The indications for surgery in patients with Crohn’s disease are the same whether performed laparoscopically or open. Surgery is indicated for the complications of the disease. The most common are obstruction, infection (abscess and phlegmon), fistulization, and free perforation (rare). Table 1 All of the complications are based on the pathophysiology of this disease. Regarding obstruction, it is much easier to do laparoscopic-assisted bowel surgery in the elective situation. Acute obstruction requiring surgical intervention has been uncommon in the author’s experience. This is almost always an on-going acute inflammatory process that should be treated first. This always includes intravenous antibiotics and, frequently, nasogastric tube decompression. I encourage all patients with obstructive symptoms to think about elective surgery, if they have been treated medically and have failed to respond. Infectious complications such as abscess and phlegmon should be treated with intravenous antibiotics. True abscess formation should be drained percutaneously prior to 4 surgery. This will decrease the inflammatory process, and it will ease the technical aspects of the surgery. ‘This is true in both laparoscopic and traditional surgery. If an abscess develops, then a fistula will be present. In the author’s experience, abscess will almost always require resection to treat. Recurrence is very high unless the diseased portion of bowel that caused it is removed. Fistulization is commonplace in Crohn’s disease. Fistulas in and of themselves are usually not indications for surgery. However, they frequently cause symptoms, which can only be treated by resection. There is a lot of interest in the medical closure of fistulas. In some cases, they can be closed without surgery. However, fistulization to the bladder, vagina, stomach or skin usually are surgically treated, because patients don’t like to have them for any length of time. If patients have had previous open surgery, they are still candidates for the laparoscopic approach. If possible, the original operative report should be reviewed so that the type of anastomosis is known in advance. It will make it easier to recognize it at the time of surgery. Diagnostic laparoscopy also has a role in the diagnosis of Crohn’s disease. A small group of patients need confirmation of disease before institution of therapy. It is a mistake to treat with immunosuppressive therapy without confirmation of disease. These are patients who do not have the terminal ileum diseased, and the small bowel series may not pick up the inflammatory segment. Colonoscopy will not confirm disease in these patients either. There has been a lot of interest in capsule endoscopy in just this setting. Recent reports are favorable with this new modality. All patients with Crohn’s disease requiring surgery are considered potential candidates for laparoscopic-assisted resection or bypass. Table II lists the procedures performed in the author’s series. As can be clearly seen, previous surgery is not a contraindication to laparoscopic surgery. Patients with multiple areas of involvement are also potential candidates for laparoscopic surgery. Table III 5 details the multiple procedures performed in this series. It is important to have experience in the straightforward cases before attempting the more complex cases. The best operative case in Crohn’s disease is limited terminal ileal disease (less the 12 inches) without fistula, phlegmon, or abscess. In fact, the shorter the disease process, the more benefit the patient will likely have with surgery (compared to medical therapy). There is some interest in medical circles to resect short segment disease, thereby making the patient grossly disease free. Then, patients are treated prophylactically to delay or prevent recurrence of disease. The preoperative evaluation of these patients is important, including a good history and physical exam. It is especially important to know if the patient is taking exogenous steroids, and whether or not the patient has had previous surgery. The presence of a palpable mass (phlegmon or abscess) usually indicates a difficult dissection. Contrast studies of both the upper and lower gastrointestinal tracts are important. CT scan of the abdomen should be done with contrast. Capsule endoscopy is becoming more prevalent in clinical practice, but its role in Crohn’s disease is not yet established with certainty. EGD and colonoscopy are commonplace. Colonoscopy is performed before surgery in all patients to identify fistulous disease in the colon. It is not uncommon to pick up an incidental ileosigmoid fistula. Table IV details the various fistulas present in this series. Table V lists the abscesses encountered. Anesthetic Considerations I prefer that nitrous oxide not be used for bowel cases. This is especially true with Crohn’s patients, as intestinal obstruction is a common indication for the surgery. If the anesthesiologist insists, then it can be instituted after the bowel has been resected, and the assisted incision has been closed. The other issue 6 has to do with fluid replacement and maintenance during the procedure and in the post anesthesia care unit. All patients have undergone bowel prep, and by definition, are dehydrated. However, I prefer to keep the patients on the “dry” side. There is data to support fewer complications when patients are not overhydrated. Postoperative Care A nasogastric tube is not utilized in these patients. The Foley® catheter is removed the next morning, if the patient is not having a lot of pain, and there is wasn’t a bladder fistula. Oral oxycodone and intravenous Toradol® are used for pain relief. In 95% of the patients, this is all that is required. Patient controlled analgesia is not used routinely. The patients are out of bed on the first postoperative night. This is possible in more than 80% of the patients. Pneumatic compression stocking are used while the patients are in bed. Clear fluid diet is begun on the first evening, and it is advanced to solid food (low residue) as soon as the patient passes flatus. Full fluids are not used. Intravenous fluids are kept to a minimum averaging 75cc/hr the first two days post operatively. Anti nausea medication is occasionally needed the first postoperative night, but rarely required past that time. Antibiotics are not used unless there is a specific reason to do so. Forty percent of the patients in this series are on immunosuppressive medication of some sort. Approximately 20% of the patients were on steroids. With laparoscopic surgery, there has been no need to boost steroids. These patients are placed back on their preoperative level immediately post surgery, and a gradual taper is begun while in the hospital. This is distinctly different from open surgery where the stress response requiring a steroid boost is more marked. Table VI details the complications in this series. 7 Table I INDICATIONS N Diagnosis 14 Obstruction 171 Pain (fistula) 46 Abscess 7 Perforation 2 Duodenal 9 obstruction 249 8 Table II Procedure N Diagnostic 14 Gastrojejunostomy 9 1_ ileocolic 119 2_ ileocolic 53 3_ ileocolic 12 4_ ileocolic 3 SB resection (1 Secondary) 27 R hemicolectomy 8 Sigmoid resection 9 Subtotal colectomy 9 9 L hemicolectomy 8 Anterior resection 4 Total colectomy 1 Stricturoplasty 2 Ileo-rectal (Hartmann’s) 1 TABLE III Ileocolic + Small bowel resection+ Small bowel resection (27) Ileostomy revision Sigmoid resection (5) BSO. Stricturoplasty Cholecystectomy (3) Tubal ligation (1) Left Colon resection (1) 10 TABLE IV Site N Entero-entero 52 Entero-abdominal wall 29 Ileo-sigmoid 32 Ileo-vesical 13 Ileo-tranverse colon 6 Colo-vesical 2 Colo-duodenal 2 TABLE V ABSCESS N Right lower quadrant ( 3 psoas) 11* Pelvic 4** * 9 primary ileocolic, 2 secondary ileocolic 11 ** 3 sigmoid disease, 1 ileal disease TABLE VI COMPLICATION * N SB obstruction 12* Intestinal leak 4** Post-op bleed 2*** Wound infection 1 UTI 1 C. Diff 1 5 Reoperations (3 laparoscopic, 2 traditional ** 2 Reoperations *** 1 Immediate reoperation 12 Suggested Readings 1. Bernstein Cn, Blanchard JF, Rawsthorne P et al. Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in a central Canadian province: a population based study. Am J Epidemiol 1999; May 15(10): 916-24. 2. Duepree HJ, Senagore AJ, Delaney CP et al. Advantages of laparoscopic resection of ileocecal Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum 2002; May 45(5): 605-10. 3. Hasegawa H, Watanabe M, Okabayaski et al. Laparoscopic surgery for recurrent Crohn’s disease. Br J Surg 2003; Aug 90(8): 970-73. 4. Reissman P, Salky BA, Edye M et al. Laparoscopic surgery in Crohn’s disease. Indications and results. Surg Endosc 1996; Dec 10(12): 201-3. 5. Wu JS, Birnbaum EH, Kodner IJ et al. Laparoscopic-assisted ileocolic resection in patients withCroohn’s disease: are abscesses, phlegmonns or recurrent disease contraindications? Surgery 1997; Oct 122(4): 682-8. 6. Milsom JW, Hammerhofer KA, Bohm B et al. Prospective, randomized trial comparing laparoscopic surgery vs. conventional surgery for refractory ileocolic Crohn’s disease. Dis colon Rectum 2001; Jan 44(1) 1-8. 13 7. Canin-Endres J, Salky B, Gattorno F et al. Laparoscopically assisted intestinal resection in 88 patients with Crohn’s disease. Surg Endosc 1999; 13: 595-99. 8. Moorthey K, Shaul T, Foley RJ. Factors that predict conversion in patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery for Crohn’s disease. Am J Surg 2004; Jan 187(1): 47-51. 9. Schmidt CM, Talamini MA, Kaufman HS et al. Laparoscopic surgery for Crohn’s disease: reasons for conversions. Ann Surg 2001; 6: 733-39. 10. Brandstrup B, Tonnesen H, Beier-Holgersen R et al. Effects of intravenous fluid Restriction on postoperative complications: Comparison of two perioperative Fluid regimens: A randomized assessor-blinded multicenter trial. Ann Surg 2003; Nov 2328(5): 641-48. 14