An Advisory Advantage - Institute for Student Achievement

advertisement

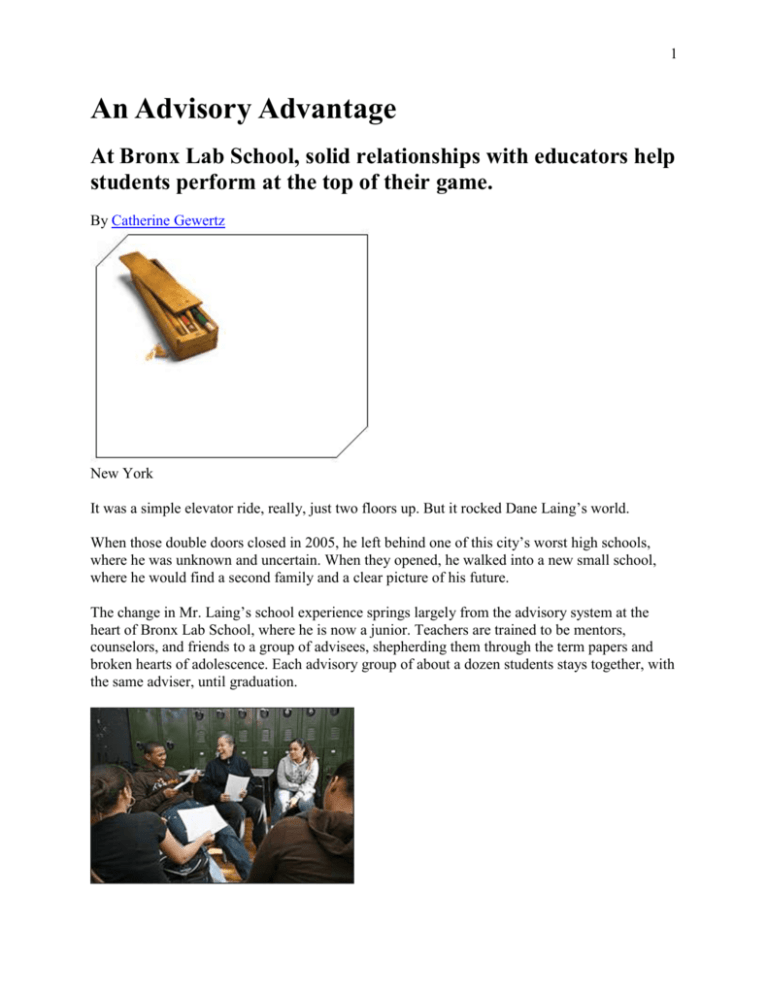

1 An Advisory Advantage At Bronx Lab School, solid relationships with educators help students perform at the top of their game. By Catherine Gewertz New York It was a simple elevator ride, really, just two floors up. But it rocked Dane Laing’s world. When those double doors closed in 2005, he left behind one of this city’s worst high schools, where he was unknown and uncertain. When they opened, he walked into a new small school, where he would find a second family and a clear picture of his future. The change in Mr. Laing’s school experience springs largely from the advisory system at the heart of Bronx Lab School, where he is now a junior. Teachers are trained to be mentors, counselors, and friends to a group of advisees, shepherding them through the term papers and broken hearts of adolescence. Each advisory group of about a dozen students stays together, with the same adviser, until graduation. 2 Christine Bernard, center, leads an advisory group with students Juan Tejada, left, and D'Larys Rivera. —Photo by Emile Wamsteker “She’s like my second mom,” Mr. Laing, a soft-spoken 17-year-old with a headful of beaded braids, said about his adviser, English teacher Christine Bernard. “I can talk to her about college, music, things with my girlfriend. I feel so attached to her. It helps me do everything I’ve got to do.” By creating that kind of culture, with promising indicators that it’s paying off academically, Bronx Lab appears to be succeeding at something that has eluded many a high school: creating effective advisories. Some form of advisory has long been commonplace in private schools, where many students get regular guidance and support from teachers who know them well. In the past few decades, public middle and high schools have tried with limited success to provide similar supports. Often, they end up being little more than a regularly scheduled study hall. The small-schools movement, with its emphasis on personalization, took the idea of advisory as a cornerstone. But experts say that even in those more intimate settings, the system often falls short of its promise as staff members, overwhelmed with the demands of starting a new school, find it impossible to procure the very substantial time and training necessary to make it successful. When Bronx Lab opened in September 2004, it was yet another small school determined to make advisory work. It grabbed a bit of space inside the 2,600-student Evander Childs High School, which was so disrupted by violence and high dropout rates that New York City had decided to phase it out, leaving space for six small schools. Now in its third year in expanded digs on the massive building’s fourth floor, Bronx Lab has 300 freshmen, sophomores, and juniors. It plans to enroll students in grades 9-12 next year. Math teacher Mike Ziolkowski, at right, evaluates a history presentation with La'Nae Richards, left, and Daja Lake. —Photo by Emile Wamsteker 3 From the start, Bronx Lab used a school model that features “distributed counseling,” meaning that all faculty and staff members, not just a handful of experts, are trained to advise and support students on academic as well as personal issues. The approach was developed by the Institute for Student Achievement, a Lake Success, N.Y.-based nonprofit organization that provides technical support and training to 65 schools using the model in four states. All institute schools follow seven common principles, including distributed counseling, continuous professional development, and an extended-day, college-preparatory curriculum for all students. Promising Signs On several indicators, students attending the Bronx Lab School are faring better than those in other New York City schools. Passing Rates on Regents Exams Bronx Lab (For the class of 2008, the school’s first entering class): • English 75% • Math A 88% • Global History 74% N.Y.C. High Schools (For the class of 2006; most recent data available): • English 50% • Math A 54% • Global History 53% Average Attendance 2004-05 • Bronx Lab 92% • N.Y.C. 82.5% Promotion, grade 9 to 10, 2005-06 • Bronx Lab 92% • N.Y.C. 73% Note: The Bronx Lab data are principal’s unaudited figures. Citywide data are from the New York City Department of Education. In the institute’s model, distributed counseling and advisory groups do not function in isolation. They are integral parts of a relationship-driven, collaborative way of running a high school. That means that relationships between students and adults can’t be just soft-and-fuzzy enhancements to school life, but genuine bonds that enable students to perform at the top of their game. “That leverage is at the heart of the distributed-counseling model,” N. Gerry House, the institute’s president and chief executive officer, said in a sunny hallway during a recent visit to Bronx Lab. “If you have trusting relationships, you can demand more of students academically, because they know that in addition to the demands we are making, there is the support.” 4 To achieve that in middle and high school would mirror practice that’s long been embedded in elementary education, said Ms. House, a former superintendent of the Memphis, Tenn., schools and high school English teacher. In the elementary grades, it’s a given that teachers facilitate learning by building community in their classrooms, she said. But by high school, “it’s assumed that it’s all about imparting content, and it gets separated from the students themselves. That’s an erroneous road to go down.” For high school teachers accustomed to a more traditional approach, taking on the added roles of counselor and mentor can prove difficult. “It’s a hard shift if you’re not used to this paradigm,” said Sarah Eustis, a former middle school social studies teacher who is now Bronx Lab’s assistant principal (and, like most other adults at the school, leads her own advisory group as well). “It’s another element, definitely, but it’s a really important part of everything we do. We’re talking about casting a net to let all of us get our arms around all of these kids.” At Bronx Lab, advisories meet four times a week for 45 minutes. Two sessions are devoted to silent reading, since many of the school’s students, nearly all of whom are from low-income families, don’t typically curl up with books. Two other weekly sessions encompass a range of activities from the academic to the personal. In one of Ms. Bernard’s advisories recently, 11 teenagers sat in a circle. The teacher returned the latest round in a letter correspondence she’s having with each of them about books they’re reading, and how they relate to their own lives. The conversation turned for a moment to two of the students and which courses they would choose for next term, and then to whether anyone in the group might join the school’s summer trip to Ecuador. The Ingredients of Successful Advisories Education consultant Rachel A. Poliner, who helps schools across the nation set up advisory programs, suggests things to keep in mind when considering such a system. “Too many schools schedule advisories before they have consensus, a plan, and resources,” she says. 1. Plan Take the planning process seriously. Set up a research-and-design team that reviews the research on advisories and visits schools with effective advisory systems. Designate people to be in charge of coordinating the design and the advisory program itself once it is set up. 2. Engage Engage in extensive outreach to gather the suggestions and support of faculty members, students, parents, and key district leaders. Start with goals, not scheduling. Be clear on what you want an advisory to accomplish, and let those goals drive its design. 5 3. Define Clearly define advisers’ roles and responsibilities and the procedures for coordinating, supervising, and assessing the system. 4. Train Provide ongoing, on-the-job professional development to train and support staff members in developing advisory skills. 5. Redesign Advisories can’t be effective in a vacuum. They must be part of an overall school redesign that facilitates strong relationships between students and adults and emphasizes personalized teaching and learning. 6. Size Up Size up the context in which you are operating. All the best planning and preparation can’t guarantee a good advisory if regulations or attitudes in your community are inhospitable to the idea. SOURCE: Education Week In other advisories along the hallway, students talked about how to have respectful differences of opinion about a novel, or the humiliation of screwing up a recent family dinner. On other days, topics have included balancing a checkbook, interesting events in the news, and what it might be like to leave home for college. Ms. Bernard said later that the advisory curriculum—and there is one—is deliberately broad and flexible enough to mesh intellectual and emotional issues. “It’s riding it together, teaching them what family is all about,” said Ms. Bernard, one of the school’s founding teachers and also its director of instruction. But to do that, you need teachers willing and able to get close to their students. Principal Marc S. Sternberg said that in writing job descriptions and conducting interviews, he and his staff “filter pretty heavily for people whose interpersonal skills aren’t strong.” Then the training begins. For each of its schools, the Institute for Student Achievement supplies advisory-skills training in special sessions at its summer institutes and through a coach it assigns to work weekly with staff members at each site. The coach, typically a former principal, also focuses on other issues, such as designing a sound curriculum and creating a positive school culture. A second “content coach” shows teachers in each subject how to strengthen their students’ critical-thinking skills. 6 Sarah Eustis, left, the assistant vice principal, talks to student Kevin Bharrat during "history day" at Bronx Lab School. —Photo by Emile Wamsteker To mesh well with the relationship-based advisory model, Bronx Lab staffers seek to make teaching more of a joint inquiry than a handing-down of information. One recent afternoon found students in 9th grade Integrated Math and Science on their knees in the hallway, chatting as they used yardsticks to measure a stretch of the floor. They’d learned the formula for velocity, and had calculated their own walking speeds. Now they would use that knowledge to project how much time it would take to cover the allotted distance. Leadership, too, takes a collaborative form at Bronx Lab. To Mr. Sternberg, it doesn’t make sense to ground learning in close adult-student relationships and then give his staff little role in running the school. To his way of thinking, those adults are the ones who know the students, so they should share in making decisions. That philosophy was evident at a weekly school-based support-team meeting last month. The school’s assistant principal, staff social worker, special education coordinator, college-placement director, parent coordinator, and student-life director crammed themselves around a table in a tiny room with Mr. Sternberg. Over the sounds of barking dogs and car alarms outside, they hashed out a range of topics: supporting one junior behind on his credits, improving procedures for midyear transfer students, and developing a new protocol for holding academic-problem conferences with students and families. On each topic, Mr. Sternberg asked questions and guided conversation, but gave the issue back to the staff to resolve. “It can be a frustrating way of doing things, for me and for others,” he said later. “There are easier ways to make decisions. But then they’re not always good ones.” Even regular training in the Institute for Student Achievement’s model can’t cover all situations. And Bronx Lab staff members freely admit they are learning as they go. They’re still defining the roles and responsibilities of advisers, for instance. Preliminary Findings 7 These comparisons are highlights from the first year of a six-year study of five New York City schools using the Institute for Student Achievement’s model. Conducted for the institute by the Washington-based Academy for Educational Development, the study examined indicators for students in 9th and 10th grades. Attendance* • ISA schools: 89.7 percent • Other N.Y.C. schools: 84.9 percent Stability* (percent of students who remain in school annually) • ISA schools: 96.2 percent • Other N.Y.C. schools: 92.9 percent Suspension rates* • ISA schools: 48.3 per 1,000 students • Other N.Y.C. schools: 68.8 per 1,000 students Promotion rate** (portion of 9th graders in 2003-04 who were promoted to 10th grade) • ISA schools = 98 percent • Other N.Y.C. schools = 70 percent Average 9th grade credit accumulation** • ISA schools = 13 • Other N.Y.C. schools = 9.7 * These findings use 2003-04 school-level report card data from the New York City Department of Education to compare six ISA high schools with high schools operating in the city that year, controlling for differences in 8th grade achievement and family-income level. The ISA schools had lower rates of 8th grade reading and mathematics proficiency and higher rates of poverty than the comparison schools. ** These findings use individual student-achievement data from the city education department to compare 9th graders in three ISA schools with demographically similar students in non-ISA high schools of 750 students or more. Promotion figures include only students who remained in the same school for 2003-04 and 2004-05. SOURCE: Academy for Educational Development Each adviser is a student’s initial point of contact for a problem. The adviser can call on other staff members for more expertise. Personal-life help can come from social worker Ray Godwin. College issues can be addressed during a chat with Amy Christie, the college-placement director. Perhaps a meeting should be brokered with the social studies teacher, since the student’s grades are falling there. But if an adviser initiates all these meetings, what is a teacher’s role? 8 “One of the dangers of distributed counseling can be, ‘Oh, it’s someone else’s responsibility,’ ” said Ms. Eustis, the assistant principal. “We wanted to make sure that teachers didn’t abdicate their responsibility because they figured the adviser would handle it. So we’re figuring out how to deal with that.” Likewise, the advisory curriculum has needed periodic tweaking. Staff members realized, for example, that they couldn’t do the same safe-sex presentation for 9th graders as for 11th graders, nor could college conversations take the same route with younger and older students. So new content is being developed as part of a four-year toolkit for advisers. The advisory system has changed school for Dane Laing, and not just because of the support he gets in advisory-group meetings. It’s because so many adults know and guide him here that he draws such a sharp contrast between his new school and his old one. 11th graders Joicel Granados, left, Christopher Cruz, and Francisco Gonzalez create a chemistry board game. —Photo by Emile Wamsteker He thinks he had a counselor at Evander Childs, he said, but he’s not sure. He never met any of the counselors there. At Bronx Lab, he has his “second mom,” Ms. Bernard, and so many teachers checking on his grades, college plans, and overall well-being that he can’t escape them, he said with a smile. At Evander, no adult at school ever mentioned college to him. Here, he’s been on so many campus trips that he already knows, midway through his junior year, that he wants to go to Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore and become a mechanical engineer. For his schoolmate Stephanie Silva, advisory is a safe place where she can handle her problems, learn important skills, and fall back on close bonds when things get tough. But most of all, she said, her relationship with her adviser, Cara Sandberg, makes her want to go out into the big world and do well. “I want her to be proud of me,” Ms. Silva said. “I want her to say, ‘Yeah, that was my advisee.’ ” Coverage of new schooling arrangements and classroom improvement efforts is supported by a grant from the Annenberg Foundation. Vol. 26, Issue 26, Pages 22-25