Blunt Carotid Injury - Maricopa Medical Center

advertisement

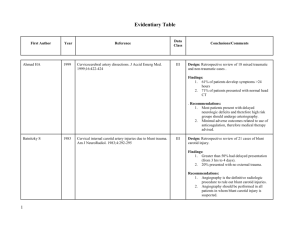

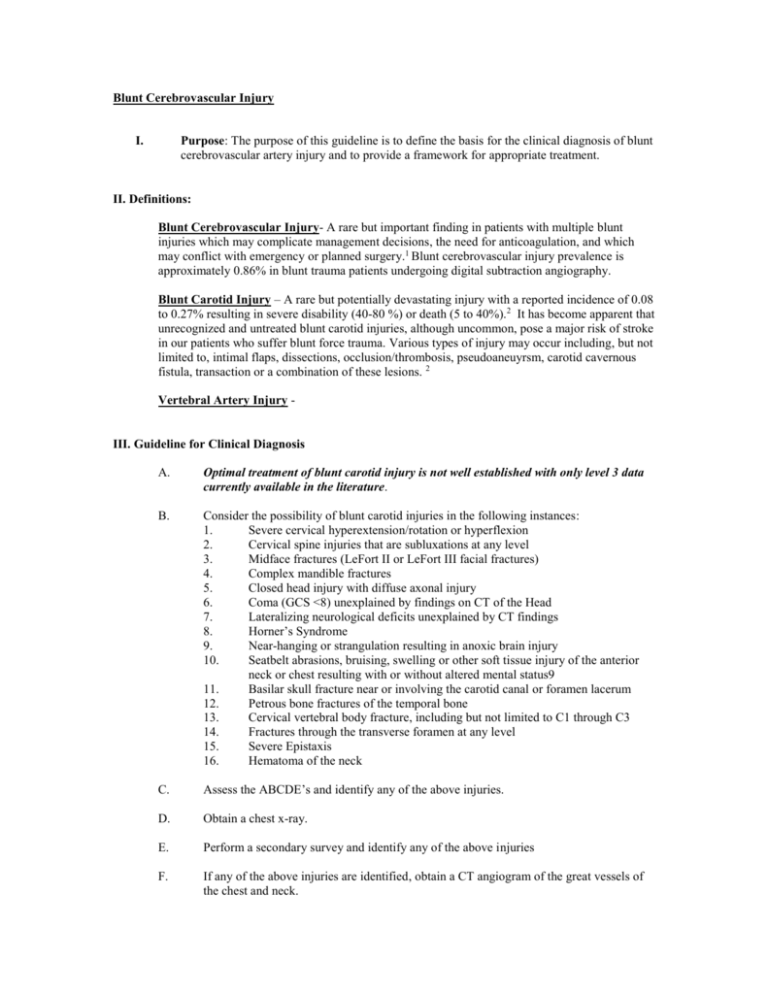

Blunt Cerebrovascular Injury I. Purpose: The purpose of this guideline is to define the basis for the clinical diagnosis of blunt cerebrovascular artery injury and to provide a framework for appropriate treatment. II. Definitions: Blunt Cerebrovascular Injury- A rare but important finding in patients with multiple blunt injuries which may complicate management decisions, the need for anticoagulation, and which may conflict with emergency or planned surgery.1 Blunt cerebrovascular injury prevalence is approximately 0.86% in blunt trauma patients undergoing digital subtraction angiography. Blunt Carotid Injury – A rare but potentially devastating injury with a reported incidence of 0.08 to 0.27% resulting in severe disability (40-80 %) or death (5 to 40%).2 It has become apparent that unrecognized and untreated blunt carotid injuries, although uncommon, pose a major risk of stroke in our patients who suffer blunt force trauma. Various types of injury may occur including, but not limited to, intimal flaps, dissections, occlusion/thrombosis, pseudoaneuyrsm, carotid cavernous fistula, transaction or a combination of these lesions. 2 Vertebral Artery Injury - III. Guideline for Clinical Diagnosis A. Optimal treatment of blunt carotid injury is not well established with only level 3 data currently available in the literature. B. Consider the possibility of blunt carotid injuries in the following instances: 1. Severe cervical hyperextension/rotation or hyperflexion 2. Cervical spine injuries that are subluxations at any level 3. Midface fractures (LeFort II or LeFort III facial fractures) 4. Complex mandible fractures 5. Closed head injury with diffuse axonal injury 6. Coma (GCS <8) unexplained by findings on CT of the Head 7. Lateralizing neurological deficits unexplained by CT findings 8. Horner’s Syndrome 9. Near-hanging or strangulation resulting in anoxic brain injury 10. Seatbelt abrasions, bruising, swelling or other soft tissue injury of the anterior neck or chest resulting with or without altered mental status9 11. Basilar skull fracture near or involving the carotid canal or foramen lacerum 12. Petrous bone fractures of the temporal bone 13. Cervical vertebral body fracture, including but not limited to C1 through C3 14. Fractures through the transverse foramen at any level 15. Severe Epistaxis 16. Hematoma of the neck C. Assess the ABCDE’s and identify any of the above injuries. D. Obtain a chest x-ray. E. Perform a secondary survey and identify any of the above injuries F. If any of the above injuries are identified, obtain a CT angiogram of the great vessels of the chest and neck. G. If there is a suspicion of a cerebrovascular injury that cannot be adequately evaluated per a CT angiogram of the neck vessels, catheter-based cerebral angiography in the interventional suite or operating room should be used to further elucidate the nature of the injury. H. CT angiography depicts all four cerebral arteries and veins with conflicting on additional Ct scanning in the rapid trauma work-up. I. Doppler Ultrasound should not be used for ruling out blunt carotid injuries as it has inadequate sensitivity to rule out this condition. a. Albeit a rapid, cost-effective, non-invasive, and non-noncontrasted study which may be performed at the time of the on-going resuscitation along side of the Focused Abdominal Ultrasound for Trauma, the pressure to complete the study, placement of central lines and co-existing cervical collars, and tenderness to injured focal areas of the neck severely hamper the adequacy of the performance of this examination. 1 IV. Guideline for Clinical Treatment A. B. C. While it is agreed that the optimal management of cerebrovascular injury is not well defined, if a blunt carotid artery injury is identified and there is no contraindication for anticoagulation (see below), at this time anticoagulation therapy is considered best clinical practice. The goal of anticoagulation therapy is to prevent cerebral embolization and avoid permanent occlusion of that injured artery. a. Withholding anticoagulation for those patients with evidence of blunt cerebrovascular injuries with contraindications for heparin administration lead to an ischemic event in 46.3 percent of these patients. 1 The use of the appropriate form of anticoagulation has not been well established and the majority for the literature provides Level 3 data. Nonetheless, heparin therapy for 1 to 3 weeks with a target of aPTT to 40 to 50 seconds was independently associated with improvement in neuralgic outcomes and survival. Heparin therapy resulted in a decreased mortality when compared with those not on heparin treatment. 8,10 Heparin therapy was transitioned over to Coumadin (Warfarin) therapy once the patient was ready to be transitioned to oral anticoagulation. Heparin has been shown to have a higher bleeding complication rate compared to oral anti-platelet therapy. Oral anti-platelet therapy and intravenous heparin based therapy had no difference in neurologic outcomes.11 Contraindications/Precautions to Heparin Therapy2 - Hypersensitivity to heparin - Active bleeding - Severe thrombocytopenia or Heparin Induced Thrombocytopenia - Increased risk of hemorrhage (i.e. severe liver or splenic laceration/contusion, intracranial hemorrhage, spinal cord injury - Free fluid in the abdomen with a solid organ injury being observed - Aortic dissection (increased risk of hemorrhage) - Treatment with drotrecogin alpha (activated) (Xigris) (increased risk of hemorrhage) - Hemophilia or other blood disorders (increased risk of hemorrhage) - Epidural catheter (increased risk of hemorrhage) - Subacute bacterial endocarditis (increased risk of hemorrhage) - Uncontrolled hypertension (increased risk of hemorrhage) - Previous hypotension requiring blood transfusion in a patient with pelvis fractures, solid organ injury and free fluid in the abdomen and pelvis - Ongoing fluid resuscitation with blood and fresh frozen plasma for decreasing hematocrit and/or rising coagulation parameters (InR/PT/PTT) 1) Blunt Cerebrovascular Injury in Patients with Blunt Multiple trauma: Diagnostic Accuracy of Duplex Doppler US and Early CT Angiography. Mutze, S., Rademacher, G., Matthes, G., Hosten, M., and Stengel, D. Radiology Volume 237 (3) 884-92. 2) Anticoagulation for Blunt Carotid Artery Injury. Guidelines from the Department of Surgical Education, Orlando Regional Medical Center 3) Blunt Carotid Arterial Injuries: Implications of a New Grading Scale. Biffl, WL, Moore, E, Offner, PJ, Brega, KE, Franciose, RJ and Burch JM. Journal of Trauma November 1999, 47:5 4) Carotid Artery Trauma: Management Based on Mechanism of Injury. Fabian, TC, George, SM, Croce, MA, Mangiante, EC, Voeller GR and Kudsk, KA. The Journal of Trauma 1990, 30:8, 953-61. 5) Pediatric Blunt Carotid Injury from Low-Impact Trauma: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Cuff, RF, and Thomas, JH. The Journal of Trauma, 2005; 58:620-3. 6) Blunt carotid Artery Injuries: Difficulties with the Diagnosis Prior to Neurologic Event. Carillo, EH, Osbourne, DL, Spain, DA, Miller, FB, Senler, SO, and Richardson, JD. The Journal of Trauma1990, 46(6) 1120-5. 7) Blunt Cerebrovascular Injuries. Cothern, CC and Moore, EE, Clinics 2005, 60(6):489-96. 8) Blunt Carotid Injury (Importance of Early Diagnosis and Anticoagulant Therapy. Fabian,TC, Patton, JH, Croce, MA, Minard, G, Kudsk, KA, Pritchard FE. Annals of Surgery 1996 223 (5), 513-25. 9) Rozcki, GS, Tremblay, L, Feliciano, DV, Tchorz, K, Hattaway, A, Fountain, J, Pettitt, BJ. A Prospective Study for the Detection of Vascular Injury in Adult and Pediatric Patients with Cervicothoracic Seat Belt Signs. Journal of Trauma, 2002 52(4): 618-23. 10) Anticoagulation is the Gold Standard Therapy for Blunt Carotid Injuries to Reduce Stroke Rate. Cothern, CC, Moore, EE, Biffl WL, et al. Archives of Surgery 2004, 139:540-6. 11) Wahl, WL, Brandt, M, Thompson, et al. Anti-platelet therapy: An alternative to heparin for blunt carotid injury. Journal of Trauma 2002, 52:896-901.