UKMi Q&A xx - NHS Evidence Search

advertisement

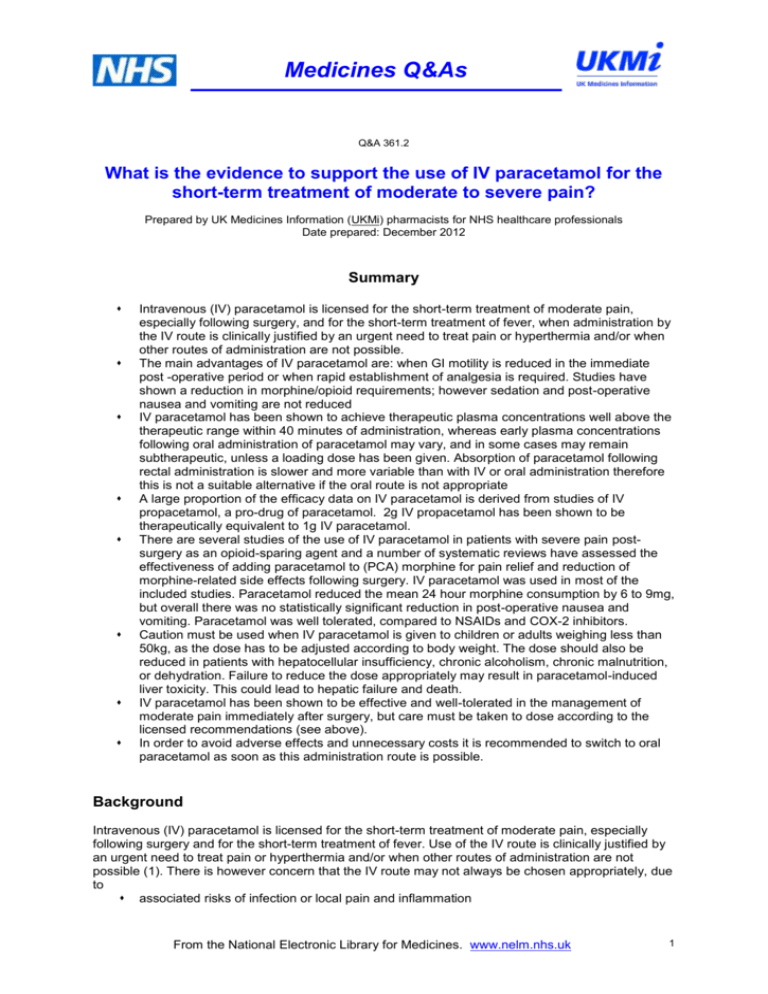

Medicines Q&As Q&A 361.2 What is the evidence to support the use of IV paracetamol for the short-term treatment of moderate to severe pain? Prepared by UK Medicines Information (UKMi) pharmacists for NHS healthcare professionals Date prepared: December 2012 Summary Intravenous (IV) paracetamol is licensed for the short-term treatment of moderate pain, especially following surgery, and for the short-term treatment of fever, when administration by the IV route is clinically justified by an urgent need to treat pain or hyperthermia and/or when other routes of administration are not possible. The main advantages of IV paracetamol are: when GI motility is reduced in the immediate post -operative period or when rapid establishment of analgesia is required. Studies have shown a reduction in morphine/opioid requirements; however sedation and post-operative nausea and vomiting are not reduced IV paracetamol has been shown to achieve therapeutic plasma concentrations well above the therapeutic range within 40 minutes of administration, whereas early plasma concentrations following oral administration of paracetamol may vary, and in some cases may remain subtherapeutic, unless a loading dose has been given. Absorption of paracetamol following rectal administration is slower and more variable than with IV or oral administration therefore this is not a suitable alternative if the oral route is not appropriate A large proportion of the efficacy data on IV paracetamol is derived from studies of IV propacetamol, a pro-drug of paracetamol. 2g IV propacetamol has been shown to be therapeutically equivalent to 1g IV paracetamol. There are several studies of the use of IV paracetamol in patients with severe pain postsurgery as an opioid-sparing agent and a number of systematic reviews have assessed the effectiveness of adding paracetamol to (PCA) morphine for pain relief and reduction of morphine-related side effects following surgery. IV paracetamol was used in most of the included studies. Paracetamol reduced the mean 24 hour morphine consumption by 6 to 9mg, but overall there was no statistically significant reduction in post-operative nausea and vomiting. Paracetamol was well tolerated, compared to NSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors. Caution must be used when IV paracetamol is given to children or adults weighing less than 50kg, as the dose has to be adjusted according to body weight. The dose should also be reduced in patients with hepatocellular insufficiency, chronic alcoholism, chronic malnutrition, or dehydration. Failure to reduce the dose appropriately may result in paracetamol-induced liver toxicity. This could lead to hepatic failure and death. IV paracetamol has been shown to be effective and well-tolerated in the management of moderate pain immediately after surgery, but care must be taken to dose according to the licensed recommendations (see above). In order to avoid adverse effects and unnecessary costs it is recommended to switch to oral paracetamol as soon as this administration route is possible. Background Intravenous (IV) paracetamol is licensed for the short-term treatment of moderate pain, especially following surgery and for the short-term treatment of fever. Use of the IV route is clinically justified by an urgent need to treat pain or hyperthermia and/or when other routes of administration are not possible (1). There is however concern that the IV route may not always be chosen appropriately, due to associated risks of infection or local pain and inflammation From the National Electronic Library for Medicines. www.nelm.nhs.uk 1 Medicines Q&As potential for overdose with concomitant orally administered medicines containing paracetamol or in patients with hepatic impairment or severe renal impairment failure to adjust the dose according to body weight or other patient-related factors increased nursing time and costs. Answer For some years paracetamol for IV use was only available (not licensed in the UK) in the form of propacetamol, a pro-drug of paracetamol. A dose of 2g of propacetamol is hydrolyzed to 1g of paracetamol (2) within 7 minutes of administration. Bioequivalence (3) and therapeutic equivalence (4) of 2g of IV propacetamol and 1g of IV paracetamol have been demonstrated. A large proportion of the efficacy data on IV paracetamol is derived from studies of IV propacetamol. Post-operative pain Pharmacokinetics IV vs Oral The manufacturer of IV paracetamol recommends the use of a suitable analgesic oral treatment as soon as this administration route is possible (1). There may be situations where this is not appropriate e.g. following abdominal or gastric surgery where normal stomach motility may not be restored for 15 hours or more, also after oral surgery, or if a rapid onset of action is required (5). Paracetamol is not absorbed in the stomach, therefore delays in gastric emptying decrease the transfer of drug to the small intestine, resulting in diminished peak plasma concentrations (6). A one-off dose of IV paracetamol in the immediate post-operative period has been suggested to achieve baseline analgesia in the sedated patient (5). The onset of analgesia occurs rapidly within 5-10 minutes of IV paracetamol administration. The peak analgesic effect is obtained in 1 hour and its duration is approximately 4-6 hours (1,4). Although oral bioavailability is good (63-89%), early plasma concentrations following oral administration may vary, and in some cases may remain subtherapeutic (7). The minimum plasma paracetamol level required for analgesia and antipyresis is thought to be 10 mcg/mL (66 micromol/L) and although not clearly defined, the therapeutic range is usually considered to be 10-20 mcg/mL (66-132 micromol/L) (8). In a small study comparing early bioavailability of paracetamol after oral or IV administration, 35 adult patients undergoing day surgery (5 groups of 7 patients) received either 1g or 2 g paracetamol tablets, 1g or 2g bicarbonate paracetamol tablets or 2g IV propacetamol. After 40 minutes IV propacetamol gave a median plasma concentration of 85 micromol/L (range 65-161). Eleven out of 28 (40%) of the patients given paracetamol orally showed undetectable plasma concentrations of paracetamol after 40 minutes. At 80 minutes after oral paracetamol the median (range) plasma concentrations were 36 (0-90) and 129 (21-306) micromol/L for the 1- and 2-g groups respectively. Three of fourteen patients who received 1g had a plasma paracetamol concentration of <10 micromol/L (8). The study did not report clinical outcomes i.e. pain relief, although pain was assessed by Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) and treated when VAS values were>4, but no details are given. In a small randomised controlled trial (RCT) 30 patients undergoing day case arthroscopy of the knee received 1g oral paracetamol 30 to 60 minutes pre-operatively(n=20) or 1g IV paracetamol intraoperatively (n=10).Plasma paracetamol levels were measured 30 minutes after arrival in the recovery room. All patients in the IV group had plasma levels above the therapeutic level compared to less than half (7/20) of the patients in the oral group. Mean plasma paracetamol levels were 88.6 micromol/l for the intravenous group and 53.2 micromol/l for the oral group (P=0.0005). There was a trend towards better analgesia and reduced duration of stay in the recovery room for the IV group, although not reaching statistical significance. There was no difference in pain scores between groups(9). However larger numbers of patients would be needed to demonstrate this at an acceptable level of significance. In an open non-blinded study patients scheduled for elective ENT surgery or orthopaedic surgery were randomised to receive 1g paracetamol either orally 30 minutes before scheduled surgery(n=52) or IV (n=54) immediately before induction of anaesthesia. Blood samples were collected 30 minutes after the first dose and then at 30 minute intervals for 240 minutes. Therapeutic plasma concentrations (≥ 10 mg/L) were reached in 67% of the oral group compared with 96% in the IV From the National Electronic Library for Medicines. www.nelm.nhs.uk 2 Medicines Q&As group. Maximum median plasma concentrations were 19 mg/L (interquartile range 15 to 23 mg/L) and 13 mg /L (interquartile range 0 to 18 mg/L) for the IV and oral group respectively(10). A comparison of the analgesic efficacy of single doses of propacetamol 2g IV and paracetamol 1g orally in 323 patients with moderate pain following hallux valgus plasty, showed a significantly greater and longer analgesic effect with the parenteral form (11). Duration of follow-up was 6 hours. The analgesic effect of paracetamol is usually attributed to the total area under the concentration versus time curve, but studies suggest that the peak concentration may also be important for the analgesic effect (10). Some centres use a higher preoperative loading oral dose of paracetamol than the licensed dose, according to the patient’s weight, followed by a higher total daily oral dose for the first postoperative 24 hours. Studies are required comparing plasma levels and analgesia achieved using these loading doses versus IV dosing (10). Preliminary evidence suggests that in patients undergoing wisdom tooth extraction under general anaesthesia, premedication with a loading dose of oral paracetamol gives similar postoperative pain relief to IV paracetamol(12). IV vs Rectal Absorption of paracetamol following rectal administration is slower and more variable than with IV or oral administration (5,7,13). High initial doses are needed to achieve therapeutic plasma concentrations (7) and therefore the rectal route is not the preferred route of administration of paracetamol for the immediate relief of post-operative pain (5). In the UK the acquisition cost of paracetamol suppositories may be higher than that of the injection, depending on brand and strength (14). Therapeutic efficacy and tolerability Paracetamol is a well-tolerated analgesic when used at normal dosages for the acute management of mild-to-moderate post-operative pain (5). Where alternative routes are unavailable, IV paracetamol is mostly used in association with NSAIDs and opioids to allow a reduced dose of these analgesics, that have a worse adverse effect profile, to be given (5), rather than as monotherapy (5,13). The Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC) states that ‘frequent’ adverse reactions at the injection site have been reported during clinical trials (pain and burning sensation) (1). However, the incidence of local adverse events such as injection-site pain and contact dermatitis is significantly lower with IV paracetamol compared with propacetamol (4,13) and comparable to placebo in two studies: 2% (4,15) and 0%(16). A number of systematic reviews have assessed the effectiveness of adding a non-opioid to (PCA) morphine for pain relief and reduction of morphine-related side effects following surgery (17).These are briefly summarised below: Paracetamol plus morphine Remy et al(18) showed that paracetamol (including propacetamol) combined with PCA morphine results in a pooled mean reduction of 9mg in morphine consumption in the first 24 hours after surgery [95% CI: -15 to -3] equivalent to a 20% reduction. Seven RCTs, mainly in orthopaedic and spinal surgery, were included. Five studies used IV paracetamol, one used oral and one used IV plus rectal paracetamol. There were 265 patients in the group with PCA morphine plus paracetamol and 226 patients in the group with PCA morphine alone. There was no statistically significant reduction in morphine-related adverse effects including urinary retention, pruritus and sedation (OR 1.3 for sedation; 95% CI 0.79 TO 2.16; P=0.3). Paracetamol administration resulted in a non-significant reduction in PONV (OR = 0.99; 95% CI, 0.64 to 1.55; P=0.98). Patient satisfaction as assessed by verbal rating scales did not differ between the groups. Elia et al (19) showed that paracetamol (including propacetamol) reduced 24-hour morphine consumption by 8.3mg [95% CI, -10.9 to -5.7]. However, there was no statistically significant reduction in PONV or sedation (19). Fifty -two RCT (4,893 patients undergoing orthopaedic, abdominal, gynaecological, spinal or thoracic surgery) were included. This review also assessed the effect of NSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors. These were associated with a statistically significant increase in adverse effects: surgical bleeding complications and renal failure, respectively. No adverse effects were noted for paracetamol (19). From the National Electronic Library for Medicines. www.nelm.nhs.uk 3 Medicines Q&As A more recent systematic review compared the effectiveness of paracetamol, NSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors in reducing cumulative morphine consumption for the first 24 hours after surgery, and associated adverse effects, when used as part of multimodal analgesia following major surgery (17), including thoracic, orthopaedic, gynaecological, obstetric and general surgery. Sixty studies were identified, 40 of which were from the previous review (19) and 20 new trials. Only 5 studies were identified that directly compared paracetamol and NSAIDs. Seven studies compared paracetamol vs. placebo. Of the 12 paracetamol studies, 9 used IV paracetamol and 3 used oral and/or rectal administration. Data was combined from 56 trials that randomised patients to four treatments including placebo. The main analysis was mixed treatment comparison (MTC) evaluating the relative effects of the four treatment classes: paracetamol, NSAIDs, COX-2 inhibitors and placebo. The mean difference in 24h morphine consumption for paracetamol was -6.34mg; 95% CI -9.02 to -3.65. NSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors were more effective than paracetamol, but the differences were small and probably of limited clinical significance. Paracetamol was well-tolerated, with no reports of surgical bleeding, compared to 2.4% of participants receiving a NSAID, based on 6 trials (n = 695) NSAIDs were only slightly more superior to paracetamol in reducing PONV (RR 0.78; 95% CI 0.51 to 1.20) and sedation (RR 0.35; 95% CI 0.04 to 3.00) in patients on PCA morphine. The most recent systematic review assessed the efficacy and safety of IV formulations of paracetamol (paracetamol or propacetamol) for treatment of acute postoperative pain in both adults and children(2). Thirty-six (3896 participants) randomized, double-blind, placebo- or active- controlled single or multiple-dose dose clinical trials of IV paracetamol or propacetamol were included. Outcomes were assessed 4 to 6 hours after first administration of IV paracetamol or propacetamol. The primary outcome was 50% or greater pain relief over 4 to 6 hours. Thirty-seven percent of participants receiving IV paracetamol/propacetamol experienced at least 50% pain relief over 4 hours compared with 16% of those receiving placebo (NNT to benefit= 4.0; 95% confidence interval (CI) 3.5 to 4.8).Participants receiving IV propacetamol/paracetamol needed 30% less opioid over 4 hours than those receiving placebo. However this did not result in a reduction in opioid-induced adverse events. Meta-analysis of efficacy comparisons between IV/propacetamol /paracetamol and active comparators (opioids or NSAIDs), were either not statistically significant, not clinically significant, or both. Meta-analysis demonstrated a statistically significant reduction in the rate of hypotension for IV paracetamol compared with NSAIDs. Similarly a comparison of data for IV paracetamol with data for opioids showed a reduction in the rate of gastrointestinal disorders in those receiving IV paracetamol. There are other studies of IV paracetamol for post-operative pain which did not meet the inclusion criteria for these systematic reviews (2,17,19), or have been published since. Some of these are summarised below. From the National Electronic Library for Medicines. www.nelm.nhs.uk 4 Medicines Q&As Table 1. Studies of IV paracetamol for pain relief after cardiac surgery Ref Trial design Petterson 200520 RCT Cattabriga 200721 Randomised,double blind, placebocontrolled trial Trial population 80 patients after CABG Treatment Primary outcome(s) Results Paracetamol 1g IV(n=39) or PO(n=38)every 6h after extubation for 15h or 14h Mean dose of ketobemidone : IV paracetamol 17.4 ± 7.9mg vs PO paracetamol 22.1 ± 8.6mg (p=0.016).No difference in incidence of PONV & in VAS scores 113 patients after cardiac surgery. All patients received tramadol for 72h. Paracetamol 1g IV (n=56) or placebo (n=57) 15 min before the end of surgery and every 6h for 72h. Mean cumulative ketobemidone administration during the study period VAS pain scores and PONV Pain as assessed by VAS. Cumulative dose of rescue IV morphine over 72h At 12,18 and 24 h, pain scores significantly lower in paracetamol group (p=0.0041, 0.0039, 0.0044 respectively) 48mg vs 97mg (p=0.274) paracetamol vs placebo) Table 2. Studies of IV paracetamol for pain relief in other types of surgery or trauma Ref Mitra 201222 Trial design Double blind RCT Trial population 204 women undergoing caesarean section Craig 201123 Randomised, double blind pilot study 55 patients aged 16-65 with isolated limb trauma and moderate to severe pain Treatment 100mg diclofenac PR 8hourly for 24h plus IV paracetamol 1g 6-hourly or 100mg diclofenac PR 8-hourly for 24h plus IV tramadol 75mg 6-hourly. IV paracetamol 1g (n=27) or IV morphine 10mg(n=28) Primary outcome(s) Sum of timeweighted pain intensity scores over 24 h as an AUC Results Overall pain score for the observation period significantly lower in the diclofenac-tramadol group (31.82 vs 38.67 [P=0.039] but associated with significantly more nausea 15% vs 2%, P=0.001) Pain score assessed by VAS at 0, 5, 15, 30 and 60 min No significant difference in analgesic effect between paracetamol and morphine at any time interval. Fewer adverse effects in paracetamol group (8 vs. 2 patients) From the National Electronic Library for Medicines. www.nelm.nhs.uk 5 Medicines Q&As Gehling 201024 Double-blind, placebo-controlled RCT 140 patients after thyroid or parathyroid surgery Memis 201025 Randomised, placebo- controlled trial 40 patients after complex major abdominal or pelvic surgery Kurcuoglu 201026 Non-randomised comparative study 54 patients after septoplasty Yalcin 201227 Randomised, placebo-controlled trial 90 patients undergoing total abdominal hysterectomy. Anaesthesia maintained with remifentanil infusion IV parecoxib 80mg(n=35) or IV paracetamol 5g(n=35)[given as a bolus 30 min before the end of surgery , followed by an infusion over 24h], or parecoxib 80mg + paracetamol 5g(n=35), in 24 h IV paracetamol 1g + IV pethidine (n=20) every 6h [PP] or IV pethidine (n=20) for 24 h [P]. Pethidine dose determined by BPS and VAS scores. IV paracetamol 1g every 6h (n=27) or IM diclofenac 75mg 12-hourly IV ketamine 0.5mg/kg bolus followed by infusion intra-operatively(n=26)or IV paracetamol 1g infusion before induction of anaesthesia(n=26) Total opioid requirement over 24 h. (Rescue analgesia provided by piritramide delivered by a PCA). Total opioid consumption in 24h reduced significantly in all three groups compared with placebo. Eight hours and 24h after surgery, parecoxib was superior to paracetamol, compared with placebo. Pethidine consumption in 24 h and opioid adverse effects. Total pethidine consumption reduced significantly in the PP group compared with the P group, (77mg vs. 198mg). Significantly less nausea and vomiting [7 vs 1, (p<0.05)]. Significantly less sedation at extubation and at 24h in PP group Post-operative pain as assessed by VAS Pain scores lower in diclofenac group but difference not statistically significant (p >0.05). Post-operative pain as assessed by VAS for 24h,pressure pain thresholds at the incision region and morphine consumption at 24h and 48h No significant difference between the paracetamol and ketamine groups for VAS scores and pain thresholds, but morphine consumption was higher in the paracetamol group Glossary AE AUC BPS CABG CI IM Adverse effects Area under the curve Behavioural Pain Scale Coronary artery bypass graft Confidence intervals Intramuscular From the National Electronic Library for Medicines. www.nelm.nhs.uk 6 Medicines Q&As NS NSAID OR PR PCA PONV RCT RR VAS VRS Not Significant Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug Odds Ratio Rectal administration Patient-controlled analgesia Post-operative nausea and vomiting Randomised controlled trial Risk Ratio Visual Analogue Scale Verbal Rating Scale From the National Electronic Library for Medicines. www.nelm.nhs.uk 7 Medicines Q&As Renal colic A RCT in 165 patients admitted with suspected renal colic compared single IV doses of paracetamol 1g, morphine 0.1mg/kg and placebo for pain relief. Patients were excluded if they needed rescue analgesics within the first 30 minutes of the study, so 146 patients were included in the final analysis. The mean reduction in VAS pain intensity scores at 30 minutes was 43 mm for paracetamol (95% CI 35 to 51mm), 40 (29 to 52 mm) for morphine, and 27 (19 to 34 mm) for placebo. There was no difference in pain intensity reduction between paracetamol and morphine. At least one adverse event was experienced by 11(24%) receiving paracetamol 16(33%) receiving morphine and 8(16%) in the placebo group (28). In a further double-blind RCT 80 patients with renal colic received a single dose of 1g paracetamol IV (n=40) or morphine 0.1mg/kg for pain relief. 73 patients were included in the final analysis (paracetamol n=38). The difference between VAS pain reduction scores for the two groups at 30 minutes was 7.1 mm (95% CI -18 to 4); this was not clinically or statistically significant. Two adverse events were recorded in the paracetamol group and five in the morphine group (difference 9%, 95% CI -7% to 26%)(29). Adverse effects/precautions/potential risks Cases of accidental overdose have been reported during treatment with IV paracetamol 10mg/mL solution for infusion. In most cases this occurred in infants and neonates (30). However there are reports of clinical incidents involving paracetamol overdose in adult patients weighing less than 50kg, where the dose was not adjusted according to the patient’s weight (31,32). Failure to reduce the dose appropriately may result in paracetamol-induced liver toxicity. This could lead to hepatic failure and death (31,32). ). The manufacturer has reinforced this warning in a joint communication with the MHRA (33). The British National Formulary (BNF) advises that the maximum daily dose of infusions should be also reduced to 3 g for patients with hepatocellular insufficiency, chronic alcoholism, chronic malnutrition, or dehydration (14). In addition, since the infusion is presented in a rigid container (glass bottle), careful assembly and close monitoring are needed throughout the administration period and it must be stopped at the end of the infusion when the bottle is empty, in order to avoid air embolism (1,34,35). Limitations This Q&A discusses the evidence from studies in adults. The use in infants and children is not discussed. For full prescribing information please refer to the Summary of Product Characteristics Disclaimer Medicines Q&As are intended for healthcare professionals and reflect UK practice. Each Q&A relates only to the clinical scenario described. Q&As are believed to accurately reflect the medical literature at the time of writing. The authors of Medicines Q&As are not responsible for the content of external websites and links are made available solely to indicate their potential usefulness to users of NeLM. You must use your judgement to determine the accuracy and relevance of the information they contain. See NeLM for full disclaimer. Acknowledgements Dr Hannah Blanshard, Consultant Anaesthetist, Bristol Royal Infirmary References (1) Summary of Product Characteristics - Perfalgan (paracetamol). Bristol-Myers Squibb Pharmaceuticals Ltd. Accessed via http://www.medicines.org.uk/EMC/medicine/14288/SPC/Perfalgan+10mg+ml++Solution+for+Infusion/ on 23rd August 2012 [date of revision of the text 29 April 2010]. (2) Tzortzopoulou A et al. Single dose intravenous propacetamol or intravenous paracetamol for postoperative pain ( Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2011, Issue 10. Art. No.: CD007126. From the National Electronic Library for Medicines. www.nelm.nhs.uk 8 Medicines Q&As DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD007126.pub2. Accessed via http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD007126.pub2/full on 22.8.12 (3) Flouvat B et al. Bioequivalence study comparing a new paracetamol solution for injection and propacetamol after single intravenous infusion in healthy subjects. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 2004; 42: 50-7 (4) Duggan ST and Scott LJ. Intravenous paracetamol(acetaminophen).Drugs 2009;69:101-13 (5) Harding J. Postoperative pain management. Is there a role for intravenous paracetamol in postoperative pain relief? Pharmacy in Practice. March/April 2009 p.67-71 (6) Kennedy JM and van Rij AM. Drug absorption from the small intestine in immediate postoperative patients. Br J Anaesth 2006;97:171-80 (7) Oscier CD and Milner QJW. Peri-operative use of paracetamol. Anaesthesia 2009; 64: 65-72 (8) Pettersson PH et al. Early bioavailability of paracetamol after oral or intravenous administration. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2004;48:867-70 (9) Brett CN, Barnett SG, Pearson J. Postoperative plasma paracetamol levels following oral or intravenous paracetamol administration: a double-blind randomised controlled trial. Anaesthesia Intensive Care 2012; 40:166-71 (10) Van der Westhuizen J et al. Randomised controlled trial comparing oral and intravenous paracetamol (acetaminophen) plasma levels when given as preoperative analgesia. Anaesth Intensive Care 2011; 39: 242-46 (11) Jarde O et al. Parenteral versus oral route increases paracetamol efficacy. Clin Drug Invest 1997; 6: 474-481 (12) Collyer J et al. Oral vs intravenous paracetamol for wisdom tooth extractions under general anaesthesia: is oral administration equally effective? Br J Oral Maxillofacial Surgery 2012; 50S: S323(abstract) (13) Malaise O et al. Intravenous paracetamol: a review of efficacy and safety in therapeutic use. Future Neurology 2007;2:673-88 (14) Joint Formulary Committee. British National Formulary. October 2012. London: British Medical Association and Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. Accessed via http://www.bnf.org/bnf/ on 16.10.12 (15) Anonymous. Intravenous paracetamol (acetaminophen): a guide to its use in pain and fever. Drugs and therapy perspectives 2009;25:5-8 (16) Moller PL et al. Intravenous acetaminophen (paracetamol): comparable analgesic efficacy, but better local safety than its prodrug, propacetamol, for postoperative pain after third molar surgery. Anesthesia and analgesia 2005;101:90-6 (17) Mc Daid C et al. Paracetamol and selective and non-selective non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for the reduction of morphine-related side effects after major surgery: a systematic review Health Technology Assessment 2010; Vol. 14: No. 17 McDaid C et al.. Paracetamol and selective and non-selective non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for the reduction of morphine-related side effects after major surgery: a systematic review. Health Technol Assess 2010;14(17). accessed via http://www.hta.ac.uk/project/1853.asp on 17.10.12 (18) Remy C et al. Effects of acetaminophen on morphine side-effects and consumption after major surgery: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Br J Anaesthesia 2005;94:505-13 (19) Elia N et al. Does multimodal analgesia with acetaminophen, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, or selective cyclooxygenase -2 inhibitors and patient-controlled analgesia morphine offer advantages over morphine alone? Meta-analyses of randomized trials. Anesthesiology 2005;103:1296-304 (20) Pettersson PH et al. Intravenous acetaminophen reduced the use of opioids compared with oral administration after coronary artery bypass grafting. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2005;19:306-9 (21) Cattabriga I et al. Intravenous paracetamol as adjunctive treatment for postoperative pain after cardiac surgery: a double blind randomized trial. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2007;32:527-31 (22) Mitra S, Khandelwal P, Sehgal A. Diclofenac-tramadol vs. diclofenac-acetaminophen combinations for pain relief after caesarean section. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2012; 56: 706-11 (23) Craig M et al. Randomised comparison of intravenous paracetamol and intravenous morphine for acute traumatic limb pain in the emergency department. Emerg Med J published online March 1, 2011 doi: 10.1136/emj.2010.104687. Accessed online on 23.8.12 From the National Electronic Library for Medicines. www.nelm.nhs.uk 9 Medicines Q&As (24) Gehling M et al. Postoperative analgesia with parecoxib, acetaminophen and the combination of both: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in patients undergoing thyroid surgery. Brit J Anaesth 2010; 104: 761-7 (25) Memis D et al. Intravenous paracetamol reduced the use of opioids, extubation time, and opioidrelated adverse effects after major surgery in intensive care unit. J Crit Care 2010; 25: 458-62 (26) Kurkcuoglu SS et al. Pain reducing effect of parenteral paracetamol and diclofenac after septoplasty. Duzce Med J 2010; 12: 42-7 (27) Yalcin N et al. A comparison of ketamine and paracetamol for preventing remifentanil induced hyperalgesia in patients undergoing total abdominal hysterectomy. Int J Med Sci 2012; 9:327-33 (28) Bektas F et al. Intravenous paracetamol or morphine for the treatment of renal colic: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med 2009; 54: 568-74 (29) Serinken M et al. Intravenous paracetamol versus morphine for renal colic in the emergency department: a randomised double-blind controlled trial. Emerg Med J 2012; 29: 902-5 (30) MHRA Drug Safety Update July 2010;3 (12): 2-4 accessed via http://www.mhra.gov.uk/Publications/Safetyguidance/DrugSafetyUpdate/CON087803 on 14.9.10 (31) Claridge LC et al. Lesson of the Week. Acute liver failure after administration of paracetamol at the maximum recommended daily dose in adults. BMJ 341:doi:10.1136/bmj.c6764 (Published 2 December 2010) Accessed via www.bmj.com on 7.12.10 (32)Fatality due to inadvertent overdoses of intravenous paracetamol. Accessed via http://www.nelm.nhs.uk/en/NeLM-Area/News/2011---March/18/Fatality-due-to-inadvertent-overdosesof-intravenous-paracetamol/ on 9.11.12 (33) Risk of accidental overdose with Perfalgan ▼ (intravenous paracetamol). Bristol-Myers Squibb Pharmaceuticals. 26 March 2012. Accessed via http://www.mhra.gov.uk/Safetyinformation/Safetywarningsalertsandrecalls/Safetywarningsandmessag esformedicines/Monthlylistsofinformationforhealthcareprofessionalsonthesafetyofmedicines/CON1469 14 on 22.8.12 (34) Pierson R, Coupe M. Reducing the risk of air embolism following administration of IV paracetamol. Anaesthesia 2008; 63:96-107 (35) Davies I, Griffin JD. A novel risk of air embolism with intravenous paracetamol .BMJ Case Reports 2012;10.1136/bcr01.2012.5488 accessed online on 28.11.12 Quality Assurance Prepared by Julia Kuczynska, South West Medicines Information and Training, University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust Date Prepared December 2012 Checked by Trevor Beswick, South West Medicines Information and Training, University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust Date of check 13 February 2013 Search strategy Medline: exp *ACETAMINOPHEN and [ exp *INFUSIONS, INTRAVENOUS or exp *INJECTIONS, INTRAVENOUS] or "paracetamol infusion".ti,ab or "paracetamol injection*".ti,ab] [Limit to: Humans] date of search 24.8.12 Embase: (PARACETAMOL/iv,pa [Limit to: Human] and exp *PAIN/ [Limit to: (Clinical Trials Clinical Trial) and Human]) PARACETAMOL/po and PARACETAMOL/iv,pa and exp *PAIN/ [Limit to: (Clinical Trials Clinical Trial) and Human]) on 24.8.12 Micromedex: Acetaminophen Drug Evaluation Monograph From the National Electronic Library for Medicines. www.nelm.nhs.uk 10 Medicines Q&As In-house database/resources Google : intravenous paracetamol site:nhs.uk NELM: “Paracetamol infusions” OR “Intravenous paracetamol” Dr Hannah Blanshard, Consultant Anaesthetist, Bristol Royal Infirmary From the National Electronic Library for Medicines. www.nelm.nhs.uk 11