AphasiaTreatment

advertisement

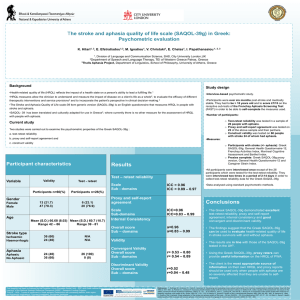

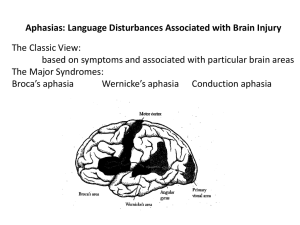

Aphasia Treatment: Evidence-based Practice and The State of the Evidence Janet Patterson, Ph.D., CCC-SLP VA Northern California Healthcare System Martinez CA and California State University East Bay Hayward CA Objectives – Define Evidence-based Practice and identify a system for evaluating the strength of the evidence – Identify evidence for impairment-based treatment techniques – Identify evidence for activity/participation-based treatment techniques – Identify evidence for emerging treatment techniques Evidence-based Practice Evidence-based medicine is the integration of best research evidence with clinical expertise and patient values. (Sackett et al. Evidence-Based Medicine: How to Practice and Teach EBM, 2nd edition. Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh, 2000, p.1) http://www.asha.org/members/ebp/intro.htm A fourth component is the environment or facility in which treatment takes place. Finding the evidence • • • ASHA National Center for EvidenceBased Practice (N-CEP) – http://www.asha.org/Members/ ebp/default/ • PsycBITE Psychological Database for Brain Impairment Treatment Efficacy – http://www.psycbite.com • Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality – http://www.guideline.gov/ • The Cochrane Collaboration – http://www.cochrane.org/ • Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine – http://www.cebm.net/ ASHA Division 2 – http://www.asha.org/members/ divs/div_2.htm ANCDS – www.ancds.org SORTing the Evidence By Outcome Measures • Patient-oriented evidence measures outcomes that matter to patients • Disease-oriented evidence measures intermediate, physiologic, or surrogate end points that may or may not reflect improvements in patient outcomes Ebell, Siwek, Weiss, Woolf, Susman, Ewigman & Bowman, 2004 Grading the Evidence The grade of a recommendation for clinical practice is based on a body of evidence (typically more than one study). This approach takes into account 1) the level of evidence of individual studies; 2) the type of outcomes measured by these studies (patient-oriented or disease-oriented); 3) the number, consistency, and coherence of the evidence as a whole; and 4) the relationship between benefits, harms, and costs. Ebell, et al., 2003 Strength of recommendation A = Consistent, good-quality patient-oriented evidence B = Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence C = Consensus, disease-oriented evidence, usual practice, expert opinion, or case series for studies of diagnosis, treatment, prevention, or screening Ebell, et al., 2003 ASHA & Evidence • National Center for Evidence-based Practice – Compendium of evidence – Systematic Reviews – Evidence Maps • Advisory Committee on Evidence-based Practice – Guides the work of N-CEP – Identify clinical questions ASHA Homepage > Research Tab > Evidence-based Practice ANCDS & Evidence • Writing Groups • Practice Guidelines Cautions • Study quality Strength of evidence Practice Guidelines • Methodology is often inconsistent • The lack of evidence = poor evidence • Consider all EBP components in treatment decisions A Word about Effect size • Many methods of calculation • Most common method references means and variability of two groups – d = (M post-treatment – M pre-treatment) SD Pre-treatment – Between or within subjects – .2 = small .5 = medium .8 = large (Cohen, 1962) • Single subject designs (Beeson & Robey, 2008) APHASIA TREATMENT Aphasia language treatment • Treatment is beneficial – Kelly, Brady & Enderby (2010) • http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/o/cochrane/clsysrev/arti cles/CD000425/frame.html – Robey (1998, 1994) – Salter, Teasell, Bhogal, Zettler, Foley (2010) • http://www.ebrsr.com/reviews_list.php • Insufficient evidence to state which treatment for which patient in which dosage IMPAIRMENT-BASED TREATMENT TECHNIQUES Impairment-based treatment techniques • • • • • • • Lexical retrieval Constraint-Induced Language Treatment Cueing Hierarchy Semantic Feature Therapy Reading Writing Complexity Account of Treatment Effectiveness LEXICAL RETRIEVAL Theoretical Foundation • Semantic network or feature network – A way of thinking about knowledge in which there are concepts and relationships among them. – A diagrammatic representation comprising some combination of boxes, arrows and labels. • Storage, central processing or retrieval deficit Collins & Loftus, 1975 Example of a semantic network • A concept (bird) defined as set of features – defining features - necessary to the meaning of the item (robin has a red breast) – characteristic features - descriptive but not essential • How close is target to exemplar – Target = chicken, sparrow, robin, penguin – Exemplar = robin Smith, Shoben & Rips, 1974 Example of semantic feature set Cognitive neuropsychological processing model of word retrieval Kay, Lesser & Coltheart, 1992 Treatment examples • Stimulation-facilitation (Schuell, 1964) • Cues – Cueing hierarchy (Linebaugh & Lehner, 1977; Patterson, 2001) – Semantic or Phonologic (Raymer et al., 1993; Wambaugh et al., 2002) – Personal cues (Marshall, Karow, Freed & Babcock, 2002) – Semantic Features (Boyle & Coelho, 1995) • Gesture (Raymer, Singletary, Rodriguez , Ciampitti, Heilman & Rothi , 2006; Rose, Douglas & Matyas, 2002) Evidence, ES & Conclusions • Evidence – – – – Some RCTs but not large scale clinical trials No Systematic Reviews One meta analyses (Wisenburn & Mahoney, 2009) Many single subject designs or case studies • Effect Sizes – Robey & Beeson (2005) reported tentative ES of 4.0, 7.0 and 10.1 calculated from 12 studies • Point is that Cohen’s d is meant for group studies and much of our work is single subject studies, requiring a different comparison – Compare an individual study to these benchmarks RCT Effect Size favoring treatment for naming outcome measure Treated items Naming Naming Task Specific v General Individual v Group PICA AAT SLP v Volunteer PICA AAT Effect Size Conventional v Functional AAT PALPA Treatment v Social Support Word Fluency Object Naming Test Treatment v No Treatment WAB Naming BNT 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 Kelly, Brady & Enderby, 2010 • Consistent results across sources of evidence – RCT, EBSR, individual review • Moderate to strong evidence in favor of treatment – Task specific and item specific effects • Phonological v semantic cueing • Noun v verb training • Weak evidence in favor of generalization to untreated items and maintenance • Insufficient evidence to state which treatment for which patient in which dosage CONSTRAINT INDUCED LANGUAGE THERAPY Theoretical Foundation • Pulvermller et al. (2001) reasoned that principles of CIMT could be applied to aphasia treatment • Learned non use observed in persons with aphasia – Failed communicative attempts “punished” (i.e. frustration or embarrassment) leading to even fewer attempts – Compensatory communication attempts rewarded and thus prevail – Fewer and more difficult communicative attempts occurred • Does “use it to improve it” apply to language change in persons with aphasia? Principles of CILT • Forced verbal language use and application of constraint – Verbalization required – Compensatory strategies prohibited (constrained) • Intensive treatment schedule – Massed practice – 3 hrs/day 5 days/week 2 weeks • Shaping verbal responses – Begin with words or short phrases – Move to longer and more complex utterances Model Use dependent Cortical Reorganization Neuronal plasticity – Events that regulate the capacity of the CNS to change in response to injury or physiological demands – Potential for change – Several mechanisms of change (i.e. synaptogenesis, dendritic arborization) CIMT example (Mark & Taub, 2004) CILT & Intensity Questions 10 questions (PICO format) Influence of CILT (5) Influence of Treatment Intensity (5) Two factors Aphasia: Acute vs. chronic Outcome measure: Impairment vs. Activity/Participation Maintenance Question (Intensity & CILT) Studies included in two reviews Cherney, Patterson, Raymer, Frymark, Schooling (2008, 2010) CILT Berthier et al., 2009 Breier et al., 2006, 2007, 2009 Meinzer et al., 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007a, 2007b, 2008, 2009 Faroqi-Shah et al., 2009 Pulvermuller et al., 2001, 2005 Goral & Kempler, 2009 Richter et al., 2008 Kirness & Maher, 2010 Szaflarski et al., 2008 Maher et al., 2006 Intensity Bakheit, et al., 2007 Hinckley & Craig, 1993 Basso & Caporali, 2001 Puvermuller et al., 2001 Denes et al., 1996 Ramsberger & Marie, 2007 Harnish et al., 2008 Hinckley & Carr, 2005 Raymer et al., 2006 CILT 19 studies with 202 participants Language impairment measures: CILT resulted in positive changes Communication activity/participation measures: CILT resulted in positive language outcome measure changes; one large effect size Data available mostly for people with chronic aphasia. One study showed positive effect for 3 individuals with acute aphasia. Maintenance of CILT effects: reported to lead to positive changes; again no effect sizes calculable Evolution of studies: Relatives; Reduce time; pharmacotherapy; RH activation; syntax module; multiple activities Treatment Intensity 9 studies with 170 participants Language impairment measures: Increased treatment intensity was associated with positive changes in both chronic and acute aphasia. –BUT-Bakheit et al., with 97 participants (more than ½) showed no effect of intensity Activity/Participation measures: Bakheit et al., results notwithstanding, equivocal results, favoring neither more intensive nor less intensive treatment for persons with chronic aphasia. Observations suggest that there can be complex interactions among intensity of treatment schedule, type of treatment, and type of outcome measure. Maintenance of treatment: little data; also equivocal, favoring more intense treatment for one outcome measure and less intense for the other. Impairment Activity Participation Effect Sizes favoring Constraint Induced Language Treatment for Impairment and Activity/Participation outcome measures Total # words Tense diversity Tense accuracy Proportion of well-formed sentences Proportion of sentences Memantine+CIAT prepost (CAL) Different root words # Utterances AATSpontaneous Speech Severity Repetition Naming Memantine+CIAT v Placebo+CIAT Memantine+CIAT prepost (Naming) LCI Comprehension BNT BDAE-3 VE BDAE-3 AC ANT ANELT SC ANELT AC AAT TT AAT TT AAT TT AAT Profile Therapist trained AAT Profile Relative trained AAT Profile AAT Profile WAB AQ -0.2 0.8 1.8 2.8 3.8 4.8 5.8 6.8 ACTIVITY/PARTICIPATION BASED TREATMENT TECHNIQUES Blackstone & Hunt Berg, 2006 Life Participation Approach to Aphasia Core Components • The explicit goal is enhancement of life participation. • All those affected by aphasia are entitled to service. • Both personal and environmental factors are targets of assessment and intervention. • Success is measured via documented life enhancement changes. • Emphasis is placed on availability of services as needed at all stages of life with aphasia. Chapey, Duchan, Elman, Garcia, Kagan, Lyon & Simmons Mackie (1999) Outcome Measures • Test results • Connected speech – CIUs (Brookshire & Nicholas, 1993) – Content units (Yorkston & Beukelman, 1980) • Perceptual data – Interview with PWA, family, friends or associates (Lomas et al., 1989) • Activity reports and surveys – ADLs, social occasions, conversation, job success • Quality of life (Hilary, Byng, Lamping & Smith, 2004) Activity/Participation-based treatment techniques • Group treatment • Conversation participation • Treatment for caregivers or conversation partners • Personal narratives; scripts • AAC GROUP TREATMENT Types of Group Treatment • Goal-directed – Conversation participation (Simmons-Mackie, 2000; Vickers, 1998) – Specific linguistic goal – Cooperative learning (Avent, 1997) – Reading and writing (Cherney, Merbitz & Grip, 1986; Clausen & Beeson, 2003) • Life activities (i.e. book group (Bernstein Ellis & Elman, 2006)) • Support (www.naa.org) • Information (Avent, Glista, Wallace, Jackson, Nishioka &Yip, 2004) Evidence, ES and Conclusions Effect Sizes for Group vs. Individual Treatment --- RCTs --WAB AQ WAB AQ Token Test Token Test PICA Verbal Subtest PICA Overall PICA Graphic PICA Gestural Subtest AAT Repetition Subtest AAT Overall AAT Naming Subtest AAT Comprehension Subtest -5.1 -0.1 4.9 9.9 14.9 19.9 24.9 29.9 34.9 39.9 Kelly, Brady, Enderby, 2010 Change Scores and Total Number of Participants for Studies of Group Treatment 80 70 Change Score 60 50 40 30 Participants showing positive change Number of participants 20 10 0 Salter, Teasell, Bhogal, Zettler & Foley (2010) • RCTs – Inconsistent data supporting effectiveness of group treatment over individual treatment • Limited support for social groups and language change • Other published studies – Moderate support for group treatment and language change – Varying methodology and outcome measures • Anecdotal and qualitative information – Improved quality of life (Avent & Austerman, 2003) – Feeling of community (Bernstein-Ellis & Elman, 1999) – Improved sense of self (Elman, 2007) – Safe environment in which to practice communicating – People “vote with their feet” • Number of aphasia groups increasing • Expanded variety of group types – Book group, artistic expression, theater group, exercise group, choral group CONVERSATION PARTICIPATION Script Training • Client and clinician create short, relevant scripts • Repetition until mastery – Personal cues (Freed, Marshall, Nippold, 1995) – Computer directed (Cherney, Halper, Holland & Cole, 2008) – Speech-language pathologist as trainer (Youmans, Holland, Muňoz &Bourgeois, 2005) • Insertion into connected speech situation Supported Conversation and Partner Training • Communicative competence of a PWA can be uncovered by a skilled partner – Typically family members or close friends – Consider layers of training • Partner changes behavior so PWA will change Armstrong & Mortenson More Conversation Treatment Techniques • PACE Promoting Aphasics’ Communicative Effectiveness (Davis & Wilcox, 1985) – Collaborative exchange of information • RET Response Elaboration Training (Kearns, 1985) – Expand utterance content • Conversational Coach (Hopper, Holland & Rewega, 2002) – Clinician coaches PWA and partner • Reciprocal Scaffolding (Avent & Austerman, 2003; Avent, Patterson, Lu & Small, 2009) – Apprenticeship model with communication embedded within meaningful contexts Evidence, ES, Conclusions • Script training – Approximately 15 studies • PWA have variable characteristics – Mild to moderate aphasia – Typically 6 months or more post onsets • Outcomes – – – – Improved production of practiced scripts Some generalization to other communication situations Slightly increased speaking rate Error reduction – Insufficient evidence for systematic review - yet • Partner training – Facilitate desirable behavior or inhibit undesirable behavior by partner – Evidence • Effective for improving communication of partner • Probably effective for persons with chronic aphasia • Insufficient evidence for persons with acute aphasia or changing language impairment, psychosocial adjustment or quality of life Simmons-Mackie et al., 2010; Turner & Whitworth, 2006 http://www.asha.org/members/reviews.aspx?id=7499 – Anecdotal outcome reports • Improved interaction – More successful conversation turns – Fewer interruptions – Fewer turns devoted to repair • Successful social validation • More accurate sense of partner’s aphasia • Maintenance and generalization of behavior Turner & Whitworth, 2006 More Conversation Treatment techniques • PACE and RET – Several studies investigating each treatment – Primarily positive results reported • Trained items • Untrained items • Generalization items – No systematic review of the techniques • Single subject design studies • Conversational Coaching and Reciprocal Scaffolding – Few studies investigating each treatment – Primarily positive results reported • Some generalization reported – No systematic review of the technique • Single subject design studies TREATMENT INFLUENCES Intensity and Dosage • Theories supporting treatment intensity – Hebbian cell assemblies (Hebb, 1949) – Education learning theory http://www.emtech.net/learning_theories.htm – Neuronal plasticity (Kleim & Jones, 2008) – Dosage (frequency, intensity, duration) • Early aphasia treatment research (Darley, 1972) Activity/Participation Impairment ES for Outcome Measures for studies investigating intensity of treatment Cherney, Patterson, Raymer, Frymark & Schooling, 2008; Frymark, Cherney, Patterson & Raymer, 2010 Content Units Content Analysis Communication Activity Log-SLPs2.64 Communication Activity Log-Patients Catalogue order-written-quiet Catalogue order-written-dual task Catalogue order-oral-quiet Catalogue order-oral-dual task CADL-2 Word/Picture Verification-Maintenance-lo Word/Picture Verification-Maintenance-hi Word/Picture Verification-Acquisition-lo Word/Picture Verification-Acquisition-hi WAB AQ WAB AQ WAB AQ WAB AQ Picture Naming-Maintenance-lo Picture Naming-Maintenance-hi Picture Naming-Acquisition-lo Picture Naming-Acquisition-hi Naming Naming Naming Naming Naming Naming Naming Fable retell-words Fable retell-utterances Fable retell-TTR Fable retell-MLU AAT Naming AAT Langugae Comprehension -1.2 0.8 2.8 4.8 6.8 8.8 10.8 12.8 Errorless (Reduced Error) Learning • Theoretical foundation – Initially demonstrated in animal learning – Memory rehabilitation – Error behavior can be self-reinforcing > eliminate • Contrast – Errorless learning • Error elimination • Error reduction – Errorful learning (cueing hierarchy) • Errors not controlled • Review of 27 studies • 91 outcome measures at three times – Immediate benefit = 78% yes; 25% no – Follow up benefit = 38% yes; 27% no – Generalization = 30% yes; 67% no • Variations – Aphasia type and fluency – Therapy type (expressive, receptive, mixed, nonlangugae) – Technique (Errorful, error reducing, error elimination) Fillingham, Hodgson, Sage & Lambon Ralph (2003) Neuronal Plasticity Principles of experience-dependent neural plasticity • Use it or lose it • Time matters • Use it and improve it • Salience matters • Specificity • Age matters • Repetition matters • Transference • Intensity matters • Interference Kleim & Jones, 2008; Raymer et al., 2008; Raymer, Maher, Patterson & Cherney, 2007 • Experience-dependent neuronal plasticity is the basis for learning and influences recovery – In the presence of treatment – Without treatment as one navigates the world • Research aimed at translation of neuroscience to neurorehabilitation – Neuroimaging studies – Dosage – Application of principles individually and in combination EMERGING TREATMENTS Emerging treatment techniques • Pharmacotherapy • Computer-aided treatment • Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (rTMS) • Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS) • Epidural cortical stimulation Pharmacotherapy • Drugs investigated in RCTs – Piracetam • Weak evidence in support but concern for side effects – Dextran – insufficient evidence – Bifemelane - insufficient evidence – Bromocriptine - insufficient evidence – Idebenone - insufficient evidence – Piribedil - insufficient evidence Greener, Enderby & Whurr, 2010 • Additional studies of drug therapy in aphasia – – – – – – – – Piracetam – strong, positive evidence in favor (n=5) Bromocriptine – strong evidence against (n=4) Levodopa – moderate evidence in favor (n=1) Amphetamines – moderate evidence in favor (n=2) Bifemelane – insufficient evidence (n=1) Dextran – moderate evidence against (n=1) Moclobemide – insufficient evidence (n=1) Donepizil – moderate evidence in favor during active treatment (n=2) – Memantine – moderate evidence in favor with CILT (n=1) Salter, Teasell, Bhogal, Zettler & Foley, 2010 Computer-based Treatment • Not so new but re-emerging technique – As primary treatment (Doesborgh, van de Sandt-Koenderman, Dippel, van Ahrskamp, Koustall & Visch-Brink, 2004; Cherney, Halper, Holland & Cole, 2008) – Practice of skills learned in treatment – Telehealth • Strong evidence in favor of improvement at impairment level • Limited evidence for generalization functional communication Salter, Teasell, Bhogal, Zettler & Foley, 2010 Cortical stimulation • Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (rTMS) – How it works • Noninvasive; Cause depolarization of neurons • Place electrodes on scalp at regions of interest – R perisylvian area or RH Broca’s area homologue • Induces weak electric current in rapidly changing magnetic field • Facilitates neuronal activity – Some evidence in favor • Patients with chronic nonfluent aphasia • Improvement in naming • Some improvement in spontaneous speech Salter, Teasell, Bhogal, Zettler & Foley, 2010; Martin, Naeser, Ho, Doron, Kurland, Kaplan, Wang, Nicholas, Baker, Alonso, Fregni & Pascual-Leone, 2009 • Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS) – How it works • Application of weak electrical currents (1-2 mA) to modulate the activity of neurons • Polarity determines whether excitability is increased or decreased – Limited evidence in favor • Patients with chronic nonfluent aphasia • Improvement in naming Salter, Teasell, Bhogal, Zettler & Foley, 2010; Baker, Rorden & Fridriksson, 2010 • Epidural Cortical Stimulation – How it works • Impulse generator implanted subclavicularly • Epidural electrode embedded over dura of target cortical area • Neurons stimulated; perhaps to rewire themselves – Limited evidence in favor when used with behavioral treatment • Chronic nonfluent aphasia Cherney, 2009; Cherney & Small, 2007 Summary Evidence-based medicine is the integration of best research evidence with clinical expertise and patient values N-CEP, PsychBITE, ANCDS, Division 2 are sources of evidence Aphasia therapy is effective; dosage is unclear. Moderate evidence for effectiveness of lexical retrieval treatment; weak evidence for generalization of treatment gains. Moderate evidence for effectiveness of CILT in chronic nonfluent aphasia. Moderate (small studies) or inconsistent (RCTs) support for group treatment. Modest support for script training (multiple forms). Modest support for communication partner training. Modest support for PACE and RET Greater intensity may be more effective than lesser intensity Errorless, reduced error and errorful treatment techniques are effective Principles of neuronal plasticity positively influence treatment effectiveness Inconsistent evidence supporting pharmacological treatment. Computer-based treatment effective at impairment level; inconsistent evidence for generalization. Some indication that cortical stimulation in conjunction with behavioral treatment may improve naming.