Relative versus cancer-specific survival:

assumptions and potential bias

Diana

1

Sarfati ,

1University

Matt

1

Soeberg ,

Kristie

of Otago Wellington, New Zealand

1

Carter ,

2Centre

Neil

2

Pearce ,

for Public Health Research, Massey University

Results

Background

Cancer-specific and relative survival analyses

are the two main methods of estimating net

cancer survival.

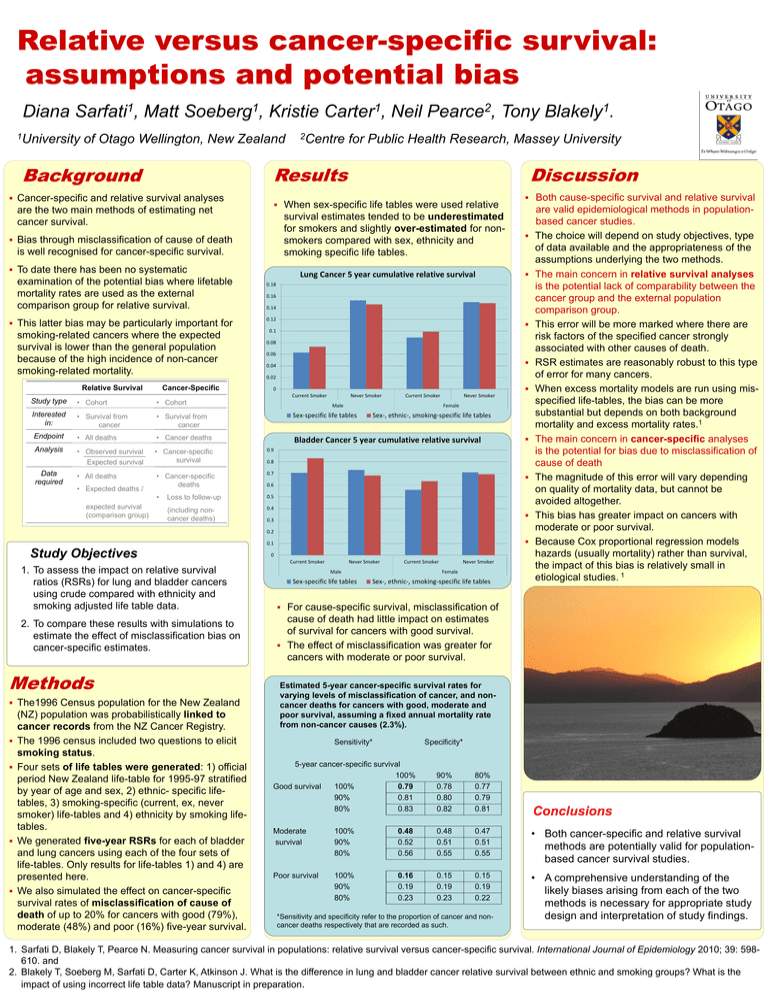

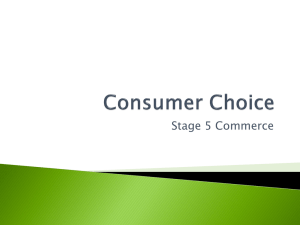

survival estimates tended to be underestimated

for smokers and slightly over-estimated for nonsmokers compared with sex, ethnicity and

smoking specific life tables.

is well recognised for cancer-specific survival.

To date there has been no systematic

examination of the potential bias where lifetable

mortality rates are used as the external

comparison group for relative survival.

This latter bias may be particularly important for

smoking-related cancers where the expected

survival is lower than the general population

because of the high incidence of non-cancer

smoking-related mortality.

Relative Survival

Cancer-Specific

Discussion

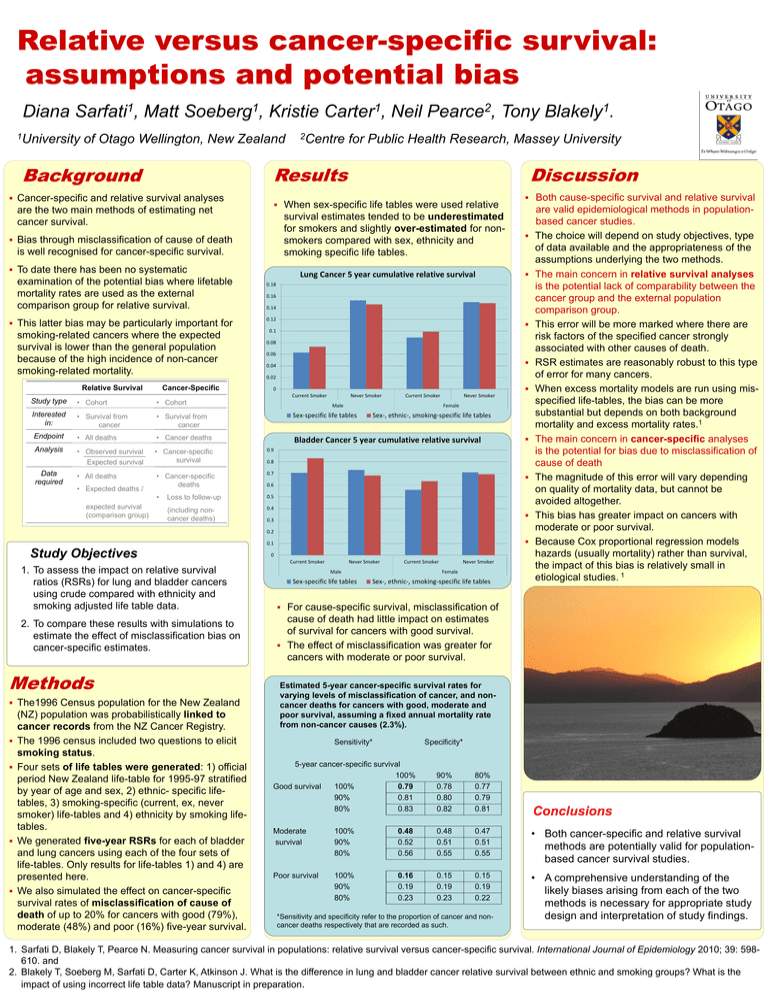

When sex-specific life tables were used relative

Bias through misclassification of cause of death

Lung Cancer 5 year cumulative relative survival

0.14

0.12

0.1

0.08

0.06

0.04

0.02

0

Current Smoker

Never Smoker

Current Smoker

Never Smoker

• Cohort

Interested

in:

• Survival from

cancer

• Survival from

cancer

Sex-specific life tables

Endpoint

• All deaths

• Cancer deaths

Bladder Cancer 5 year cumulative relative survival

Analysis

• Observed survival

Expected survival

• Cancer-specific

survival

• All deaths

• Cancer-specific

deaths

0.7

•

Loss to follow-up

0.5

(including noncancer deaths)

0.4

expected survival

(comparison group)

0.16

• Cohort

• Expected deaths /

Both cause-specific survival and relative survival

0.18

Study type

Data

required

Tony

Male

Female

Sex-, ethnic-, smoking-specific life tables

0.9

0.8

0.6

0.3

0.2

0.1

Study Objectives

1. To assess the impact on relative survival

ratios (RSRs) for lung and bladder cancers

using crude compared with ethnicity and

smoking adjusted life table data.

2. To compare these results with simulations to

estimate the effect of misclassification bias on

cancer-specific estimates.

Methods

The1996 Census population for the New Zealand

(NZ) population was probabilistically linked to

cancer records from the NZ Cancer Registry.

The 1996 census included two questions to elicit

smoking status.

Four sets of life tables were generated: 1) official

period New Zealand life-table for 1995-97 stratified

by year of age and sex, 2) ethnic- specific lifetables, 3) smoking-specific (current, ex, never

smoker) life-tables and 4) ethnicity by smoking lifetables.

We generated five-year RSRs for each of bladder

and lung cancers using each of the four sets of

life-tables. Only results for life-tables 1) and 4) are

presented here.

We also simulated the effect on cancer-specific

survival rates of misclassification of cause of

death of up to 20% for cancers with good (79%),

moderate (48%) and poor (16%) five-year survival.

0

Current Smoker

1

Blakely .

Never Smoker

Current Smoker

Male

Sex-specific life tables

Never Smoker

Female

Sex-, ethnic-, smoking-specific life tables

are valid epidemiological methods in populationbased cancer studies.

The choice will depend on study objectives, type

of data available and the appropriateness of the

assumptions underlying the two methods.

The main concern in relative survival analyses

is the potential lack of comparability between the

cancer group and the external population

comparison group.

This error will be more marked where there are

risk factors of the specified cancer strongly

associated with other causes of death.

RSR estimates are reasonably robust to this type

of error for many cancers.

When excess mortality models are run using misspecified life-tables, the bias can be more

substantial but depends on both background

mortality and excess mortality rates.1

The main concern in cancer-specific analyses

is the potential for bias due to misclassification of

cause of death

The magnitude of this error will vary depending

on quality of mortality data, but cannot be

avoided altogether.

This bias has greater impact on cancers with

moderate or poor survival.

Because Cox proportional regression models

hazards (usually mortality) rather than survival,

the impact of this bias is relatively small in

etiological studies. 1

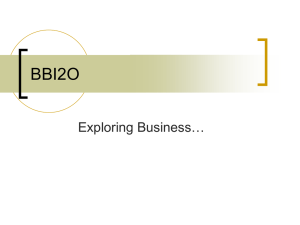

For cause-specific survival, misclassification of

cause of death had little impact on estimates

of survival for cancers with good survival.

The effect of misclassification was greater for

cancers with moderate or poor survival.

Estimated 5-year cancer-specific survival rates for

varying levels of misclassification of cancer, and noncancer deaths for cancers with good, moderate and

poor survival, assuming a fixed annual mortality rate

from non-cancer causes (2.3%).

Sensitivity*

Specificity*

5-year cancer-specific survival

100%

Good survival

100%

0.79

90%

0.81

80%

0.83

90%

0.78

0.80

0.82

80%

0.77

0.79

0.81

Conclusions

Moderate

survival

100%

90%

80%

0.48

0.52

0.56

0.48

0.51

0.55

0.47

0.51

0.55

• Both cancer-specific and relative survival

methods are potentially valid for populationbased cancer survival studies.

Poor survival

100%

90%

80%

0.16

0.19

0.23

0.15

0.19

0.23

0.15

0.19

0.22

• A comprehensive understanding of the

likely biases arising from each of the two

methods is necessary for appropriate study

design and interpretation of study findings.

*Sensitivity and specificity refer to the proportion of cancer and noncancer deaths respectively that are recorded as such.

1. Sarfati D, Blakely T, Pearce N. Measuring cancer survival in populations: relative survival versus cancer-specific survival. International Journal of Epidemiology 2010; 39: 598610. and

2. Blakely T, Soeberg M, Sarfati D, Carter K, Atkinson J. What is the difference in lung and bladder cancer relative survival between ethnic and smoking groups? What is the

impact of using incorrect life table data? Manuscript in preparation.