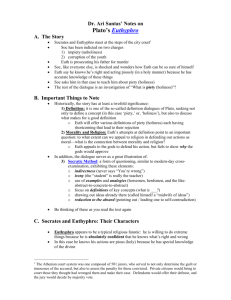

The Trial & Death of Socrates

advertisement

9/24/08 The Trial & Death of Socrates Notes on Plato's Euthyphro, Apology, and Crito Euthyphro Introductory conversation between Euthyphro and Socrates on the nature (or essence) of true "piety" (and "impiety") • • The key Greek terms discussed in the dialogue are hosion and anosion ("piety" and "impiety") and eusebeia and asebeia (often translated as "godliness" and "ungodliness"). Each of these Greek words (and their derivatives) have broad religious, personal, social, and political connotations. – Hosion ("piety") refers to a pattern of conduct, both personal and public, that is in accord with the divine order established by the will of the gods and embodied in the laws and institutions of society. – Eusebeia ("godliness") is reverence toward and obedience to whatever merits reverence and obedience, whether this be the gods, the laws of the state, social customs, parents, or anything else that deserves our reverence and obedience. • • "For the Greeks of Plato's time, both this 'piety' and this 'godliness' are closely associated with justice; the 'impious' or 'ungodly' include whatever is generally disapproved of or disallowed, whether by the community or by the gods" (Alan White). Thus, the two terms together, hosion ("piety") and eusebeia ("godliness"), can be taken to mean all of the following: holiness, righteousness, zeal in the performance of religious obligations, religious devotion, being religious, reverence, respect for the gods, respect for and loyalty to society and its laws and institutions, goodness, justice, and so forth. Anosion ("impiety") and asebeia ("ungodliness") have all of the opposite meanings. Opening Questions • Why is Socrates at the courthouse? – To answer his indictment. • Euthyphro's explanation of the indictment of Socrates – which suggests a contrast between E and S, i.e., that nobody takes E seriously. • Why is Euthyphro there? – To prosecute his own father for murder. • S's reaction to E's lawsuit – horrified surprise. • S says that he wishes to be instructed (does he, really?) by E as to the nature of true piety (and true impiety). (Socratic irony or sarcasm?) Text 61-63 E's 1st Definition of Piety • Definition by reference to instances of pious (righteous) actions (definition by example) – e.g., prosecuting criminals regardless of one's relationship with them (and failure to do so would be an example of impiety). – E's appeal to religion (i.e., the Homeric religion of ancient Greece) to support his action against his father. • S wonders whether E really believes the traditional stories about the gods, e.g., that they battle against one another? • Socrates is looking for a definition of the essence of true piety, not merely for examples of it. Text 64 E's 2d Definition of Piety • Piety as that which is dear to (loved by) the gods, and impiety is that which is hated by the gods. – But didn't E just say that the gods disagree with one another from time to time? E agrees with S that such disagreements do not concern merely factual questions (e.g., of number, size, and weight), but rather questions concerning the just and the unjust, good and evil, the honorable and the dishonorable. – S points out that E is offering a contradictory df. of piety: in some cases, the same things will be loved by some of the gods and hated by others; so the same things will be both pious and impious. – E responds by claiming that all of the gods would agree that murderers should be prosecuted and, if convicted, punished. But S wonders whether all of the gods would agree with E that E's father is guilty of murder. How does E know that all of the gods support his action against his father? (E does not answer.) – Finally, S points out that E has still not defined the essence of the pious. He has said that it is loved by the gods, but he has not said what it is. Text 65-67 E's 3d Definition of Piety (supplied by Socrates) Text 67-69 • Piety as that which is loved by all the gods [but what is it that all the gods love?]. – But is the pious and holy loved by the gods because it is pious and holy (and therefore worthy of being loved), or is it pious and holy because it is loved by the gods? • If the pious and holy is loved by the gods because it is pious and holy (E 's answer), then what? • If the pious and holy is pious and holy because the gods love it (not E's answer), then what? – Analysis of seeing, leading, and carrying [complicated]. – Cause and effect principle (applied to the occurring of an effect) [also complicated]. – The pious and holy is loved by the gods; it is loved because the gods love it. But the pious and holy is not pious and holy because it is loved by the gods; rather, the gods love it because it is pious and holy (and therefore worthy of being loved). • But then what is loved by the gods is not the same as the pious and holy, nor is the pious and holy the same as what is loved by the gods. [What?!?] The gods love the pious and holy because it is pious and holy (and therefore worthy of love); the pious and holy is not pious and holy (and worthy of love) because the gods love it. The gods do not love the pious and holy (simply) because they love it; they love it because it is pious and holy (and therefore worthy of being loved). • "[I]f that which is [pious and] holy is the same as that which is loved by the gods and that which is [pious and] holy is loved because it is [pious and] holy, then that which is loved by the gods . . . [is] loved because it is loved by the gods; but if what is loved by the gods is loved by them because it is loved by them, then that which is [pious and] holy . . . [is] [pious and] holy because it is loved by them. • "But . . . the reverse is the case, . . . they are quite different from one another. The one is loved because it is initially worthy of love; the other is worthy of love because it is initially loved." – The fact that the pious and holy is loved by the gods is only a fact about it, not its essence. Why do all the gods love the pious and holy? What is it that the pious and holy has that makes the gods love it? What is it about the pious and holy that makes it worthy of being loved? The "Daedalus" Interlude (Text 69) • Details? E's 4th Definition of Piety • Piety and moral rightness (justice?) – piety as that part of moral rightness that is concerned with the care of (or service to) the gods (the master-slave analogy). – The relationship between piety and moral rightness: piety is a part of moral rightness. Which part? The part that "attends to" the gods (as opposed to the part of moral rightness that "attends to" men [i.e., humans]). \ [analogy of fear and reverence (69-70) – fear w/o reverence but no reverence w/o fear? Justice w/o piety but no piety w/o justice? Does the analogy work?] – What does "attend to" mean here? It means "service" (re: the servantmaster relationship). But what is the point of serving the gods? Does our service to the gods benefit them or make them better? Does it enable them to accomplish something that they could not otherwise accomplish? If so, what is it? E can't say, but . . . . [next section] Text 69-72 E's 5th Definition of Piety • Piety as knowledge of how to please the gods in word and deed, through sacrifice and prayer (a "science" of sacrifice and prayer). –Prayer is asking of the gods; sacrifice is giving to the gods. If this is so, then piety "is an art which gods and men have of doing business with one another." \ But why do the gods want or need gifts from humans? How are they benefited thereby? –We give them what pleases them, what is dear to them, what they love (e.g., "tributes of honor"). \ But we have already agreed that piety is not the same as that which is loved by the gods. Either we were wrong then, or we are wrong now. Text 72-73 (In)conclusion S says that we have not yet defined the nature of piety and must therefore begin again; final (ironic/sarcastic) comment on E's case against his father; E is "in a hurry and must go now;" S's last lament. Text 73 Apology 1. Socrates' defense in response to the charges against him. 2. Socrates' conviction and the question of an alternative penalty. 3. Socrates' closing speech to the court. 1. Socrates' defense in response to the charges against him. • Opening paragraph(s) on rhetoric and truth-telling – S uses "plain style", not rhetoric and oratory. [Text 74] • The distinction between Socrates' earlier (and unnamed) accusers and his immediate accusers (Meletus, Lycon, and Anutus). [Text 74-75] • Socrates' defense against his earlier accusers. [Text 75-77] – What are the old accusations against Socrates? • • • – – He is a student of natural science (and thus denies the existence of the gods). He is a Sophist (makes the weaker argument appear to be the stronger). He teaches natural science and Sophistry in return for money. How does Socrates explain and answer the old accusations against him? • Not guilty, but . . . . • The Oracle at Delphi story. What is the nature of Socrates' special "wisdom," and what is the basis for the claim that there is no one wiser than Socrates? S 's search for someone wiser than himself (and emulated in this search by his young followers). 1. Socrates' defense in response to the charges against him, continued. • Socrates' defense against his immediate accusers (represented by Meletus). – First charge: corrupting the youth of Athens. • All Athenians improve the youth; Socrates alone corrupts them – the horse analogy (M's lack of seriousness and thoughtfulness). • Either S. does not corrupt the youth, or he does so unintentionally – either way, he should not be tried. • No reliable witnesses to this charge and many against it. – Second charge: religious heresy – the means by which S. corrupts the youth. • Meletus's charge on this subject is contradictory – he accuses S of believing in gods and not believing in gods. • S is not an atheist [but is that the official charge?]. Text 77-80 1. Socrates' defense in response to the charges against him, continued. • Socrates' portrayal of the philosophical way of life. – The "philosopher's [divinely ordained?] mission of searching into myself and other men." • To expose false claims to knowledge and wisdom. • To turn men's attention away from money, property, honor, and reputation and toward "the greatest improvement of the soul" (i.e., the cultivation of virtue). – The philosopher and the body politic – the philosopher as gadfly commissioned to keep the "great horse" of the state from going to sleep (and dying?). • And yet, the philosopher cannot occupy a public station – for then, he will not survive long. Text 80-82 1. Socrates' defense in response to the charges against him, continued. • Socrates on the conduct of judges and juries. – The personal dishonor question. – On what basis should court decisions be made? (Facts and law, not feeling.) Text 82-83 2. Socrates' conviction and the question of an alternative penalty. • Meletus calls for the death penalty. • S's proposal of an alternate penalty: – Initial [facetious/ironic] proposal: maintenance in the Prytaneum. – Consideration of alternate penalties: imprisonment, fine, exile ("The unexamined life is not worth living"). – S proposes a fine of one mina ($200), and then thirty minae ($6,000). Text 83-84 3. Socrates' closing speech to the court. • To those who voted for his execution. • To those who voted for his acquittal. – S's oracle. – Fear of death and thereafter: "No evil can happen to a good man." (What follows death – for a good person?). – S asks his friends to train his sons properly. Text 85-86 The End