Power Point Presentation

advertisement

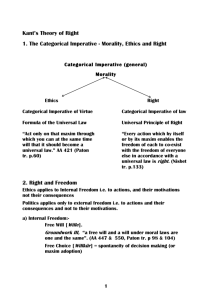

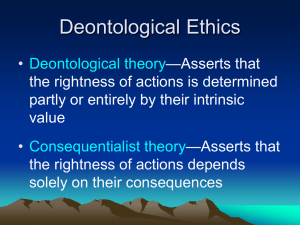

Immanuel Kant Deontology: the Ethics of Duty Kant’s Moral Theory Historical Background Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) The concept of the “good will” The concept of duty Three principles The Categorical Imperative The Hypothetical Imperative Autonomy and Heteronomy of will Kant on the concept of respect Contemporary Deontologists Good Will An action has moral worth only when performed by an agent who possesses a good will An agent has a good will only if moral obligation based on a universally valid norm is the action’s sole motive First Section, first 3 paragraphs Duty All persons must act not only in accordance with, but for the sake of, obligation A person’s motive for acting must rest in a recognition that what he or she intends is demanded by an obligation p. 2, second paragraph p. 3, last paragraph Three Principles 1. 2. 3. “An act must be done from obligation in order to have moral worth.” “An action’s moral value is due to the maxim from which it is performed, rather than to its success in realizing some desired end or purpose.” – motive of benevolence is rejected as morally unworthy “Obligation is the necessity of an action performed from respect for law.” 1. 2. 3. An action has moral worth only if a morally valid rule of obligation determines that action Even a motive of benevolence is rejected as morally unworthy, unless there is an accompanying motive of obligation Necessity comes from laws, not from mere subjective maxims. There must be an objective principle underlying willing, one that all rational agents would accept Categorical Imperative The supreme principle or moral law. Every moral agent recognizes whenever accepting an action as morally obligatory Why is the categorical imperative “imperative”? Human beings are imperfect creatures and hence need rules imposed upon These rules enjoin us to do or not to do something thus we conceive them as necessitating our action Categorical Imperative Act only in such a way in which the maxim of action can be rationally willed as a universal law It requires unconditional conformity by all rational beings, regardless of circumstances Is unconditional and applicable at all times 4 examples, p. 9 Hypothetical Imperative “If I want to obtain e, then I must obtain means m.” E.g. “If I want to buy a house, then I must work hard to make enough money for a down payment.” Maxims Maxims, according to Kant, are subjective rules that guide action. Subjective principles of volition or willing. The general rule in accordance with which the agent intends to act All actions have maxims, such as, 4/13/2015 Never lie to your friends. Never act in a way that would make your parents ashamed of you. ©Lawrence M. Hinman 10 Law Refers to the rules of conduct that rational beings lay down for themselves in the light of reason. Categorical Imperatives: Universality “Always act in such a way that the maxim of your action can be willed as a universal law of humanity.” --Immanuel Kant Categorical Imperative: Publicity Always act in such a way that you would not be embarrassed to have your actions described on the front page of The New York Times. Lying Is it possible to universalize a maxim that permits lying? What is the maxim? It’s ok to cheat when you want/need to? Can this consistently be willed as a universal law? No, it undermines itself, destroying the rational expectation of trust upon which it depends. Kant on Respect “Act in such a way that you always treat humanity, whether in your own person or in the person of any other, never simply as a means, but always at the same time as an end.” Kant on Respecting Persons Kant brought the notion of respect to the center of moral philosophy for the first time. To respect people is to treat them as ends in themselves. He sees people as autonomous, i.e., as giving the moral law to themselves. The opposite of respecting people is treating them as mere means to an end. Using People as Mere Means The Tuskegee Syphilis Experiments More than four hundred African American men infected with syphilis went untreated for four decades in a project sponsored by the government Continued until 1972 Autonomy and Heteronomy Autonomy of will is present when one knowingly governs oneself in accordance with universally valid moral principles Heteronomy of will: the will’s determination by persons or conditions other than oneself. (“heteronomy”: any source of determining influence or control over the will, internal or external, except a determination of the will by moral principles) The autonomy of the moral agent is to recognize that external authority, even if divine, can provide no criterion for morality; only our own reason that we are taking to be ultimate authority Reading: Fundamental Principles of the Metaphysic of Morals The Good Will as “good without qualification” Acting from duty vs. acting from inclination Duty as the necessity of an action done out of respect for the law The Categorical Imperative – first formulation Hypothetical vs. categorical imperatives Prudence vs. morality Applying the categorical imperative: four examples Persons as ends in themselves The Categorical Imperative – second formulation The four examples again Deontologists An act is right if, and only if, it conforms to the relevant moral obligation; and it is wrong if, and only if, it violates the relevant moral obligation They argue that the consequences of an action are irrelevant to moral evaluation They emphasize that the value of an action lies in motive, especially motives of obligation Consequences of Kantian Ethics The dignity of the human being is to be found in his moral responsibility (freedom) The dignity of the human being does not require another foundation, i.e. theological or nature The dignity of the person is the unconditional (i.e. metaphysical) ground Morality reveals the ultimate metaphysical depth of the human being. To be human is to act morally. One discovers the source of our humanity in the ability to act morally, i.e., to accept the moral imperative as finite, yet grounded in an absolute source, human freedom