The Progressive Era

1. How did progressivism and organized interest groups

reflect the new political choices of Americans?

2. Why did progressives believe in the ability of

individuals to affect positive change? How has this idea

manifested itself in political reform efforts?

3. What reforms did American women, African

Americans, and urbanites seek?

4. Why and how did President Roosevelt expand the

Federal government's power within the economy?

5. How did President Wilson seek to accommodate his

progressive principles to the realities of political power?

One needs to keep in mind the intellectual

elements of the progressive outlook and

recognize the interaction of progressive

ideas with the academic disciplines of

economics, philosophy, psychology, and

law.

and lets keep in mind as well the successes

and failures of the labor movement during

the Progressive Era. But consider in what

ways this was a turning point for the labor

movement?

And finally we must recognize the

struggles of African Americans to

secure their rights during the

Progressive Era. And the aspects of

progressive reform that undermined

blacks’ rights?

The Course of Reform

Progressive Ideas

progressivism embraces a widespread,

many-sided effort after 1900 to build a

better society there was no single

progressive constituency, agenda, or

unifying organization.

placed great faith in scientific management

and academic expertise

The urban middle class occupied the center

of progressive action as exemplified by Jane

Addams, founder of the settlement

movement and Hull House.

The urban middle class experienced a

generational crisis that reflected a crisis of

personal faith acted out by reforming

American society to meet their Christian

mission.

They felt a sense of urgency to reform

society in part because they were not

insulated from the ills of industrialism.

Progressive Ideas

The starting point for progressive thinking was

that if the facts could be known, everything else

was possible. They placed great faith in scientific

management and academic expertise and also felt

that it was important to resist ways of thinking that

discouraged purposeful action.

Progressives thought the Social Darwinists of the

Gilded Age wrong in their belief that society

developed according to fixed and unchanging laws

agreed with philosophers such as William James

William James’s doctrine - pragmatism - a

philosophical doctrine developed primarily by

William James that denied the existence of

absolute truths and argued that ideas should be

judged by their practical consequences. Problem

solving, not ultimate ends, was the proper concern

of philosophy, in James's view. Pragmatism

provided a key intellectual foundation for

progressivism.

Progressives prided themselves on being

tough-minded, but in truth were unabashed

idealists.

The progressive mode of thought nurtured a

new kind of reform journalism when, at the

turn of the century, editors discovered that

readers were most interested in the exposure

of mischief in America.

The term muckraker was given to journalists

who exposed the underside of American life;

however, in making the public aware of social

ills, muckrakers called the people to action.

Progressive leaders often grew up in homes

imbued with evangelical piety or struggled

through crises where their religious

strivings could be translated into secular

action

Reform became a major, self-sustaining

phenomenon.

The old order was challenged and changed both

politically and economically.

Reformers believed that problems could be

addressed through scientific investigation and that

people had the ability to master their environment.

Educated women found a congenial intellectual

environment in which to play an active public

role.

Religion played an underlying role in much

reform activity.

There was a drive for information gathering and a

high degree of confidence in academic expertise.

Inexpensive general-circulation magazines

containing exposés became popular reading

material.

Investigative journalism established itself as

a legitimate enterprise.

Muckraking publications attracted new

converts to progressive reform.

Exposure of municipal corruption gave rise

to reform on the local level.

Ida M. Tarbell served as

managing editor of

McClure's Magazine, where

her "History of the Standard

Oil Company” ran in serial

form for three years. Her

revelations of the ruthless

practices John D.

Rockefeller used to seize

control of the oil-refining

industry convinced readers

that it was time for

economic and political

reforms to curb the power of

big business. Tarbell grew

up in the Pennsylvania oil

region and knew firsthand

how Standard Oil crushed

competitors-- her father was

forced out of business by

Rockefeller's South

Improvement Company.

Women Progressives

Frances Kellor was a graduate of

Cornell University and worked

toward a PhD at the University of

Chicago. She lived periodically at

Hull House and joined the circle of

social reformers that congregated

there. Kellor was especially

concerned with the plight of jobless

women and their exploitation by

commercial employment agencies.

Her book Out of Work was a

pioneering investigation, paving the

way for the modern study of

unemployment. Her study on the

problems of immigrants in New

York led to the establishment of the

New York State Bureau of

Industries and Immigration in 1910.

Kellor was chosen to be its head,

the first woman to hold so high a

post in New York State government.

Middle-class women, who had long carried the

burden of humanitarian work in American cities,

were among the first to respond to the idea of

progressivism.

Josephine Shaw Lowell founded the New York

Consumers' League in 1890 to improve wages and

working conditions for female clerks in the city

stores by "white listing" progressive businesses.

The league spread to other cities and became the

National Consumers' League in 1899,and, under the

leadership of Florence Kelley, became a powerful

lobby for protective legislation for women and

children.

Among the achievements of the National Consumers'

League was the 1908 Supreme Court decision of

Muller v. Oregon, which limited women's workdays to

ten hours. Argued by Louis D. Brandeis, the case

cleared the way for a wave of protective laws for

women and children and helped usher in a

maternalistic welfare system in the United States.

Settlement houses, such as Hull House founded by

Jane Addams, helped alleviate social problems in the

slums and satisfy the middle-class residents' need to

pursue meaningful lives.

Women activists breathed new life into the suffrage

movement by underscoring the capabilities of women.

Social reformers founded the National

Women’s Trade Union League in

1903, which was financed and led by

wealthy supporters. The league

organized women workers, played a

considerable role in their strikes, and

trained working-class leaders, such as

Rose Schneiderman and Agnes Nestor.

Rose Schneiderman sought to improve the

lives of working class women through the

vote, education, and legislative protection

such as the eight-hour day and minimum

wage laws. A Polish immigrant who grew up

impoverished in New York’s Lower East

Side, Schneiderman was well acquainted

with the life of an industrial worker. She

quickly learned about trade unions and

organized her shop into the first female local

of the Jewish Socialist United Cloth and Cap

Makers’ Union. Schneiderman actively

worked for the Women’s Trade Union

League (WTUL), an organization dedicated

to unionizing working women and lobbying

for protective legislation. She had a long

career in the WTUL as well as in the

International Ladies’ Garment Workers’

Union (ILGWU), holding a variety of

leadership positions in both.

In 1897, she founded the

International Glove

Makers Union and

became its first president.

In addtion, Nestor was

involved in the Women's

Trade Union League in

which she provided

support for female

unionists through

educational work. During

1913-1948 she was the

president of the Chicago

chapter of the Women's

Trade Union League.

Inspired by British suffragists, around 1910

American suffrage activity picked up and its

tactics shifted; Alice Paul began to use

confrontational tactics to get women the vote by

rejecting the state-by-state route and advocating a

constitutional amendment that would grant the

right to vote to women everywhere.

Paul organized the militant National Woman's

Party in 1916. Meanwhile, the more mainstream

National American Woman Suffrage Association

(NA WSA) was rejuvenated under the leadership

of Carrie Chapman Catt, who organized a broadbased campaign to push for a constitutional

amendment for woman suffrage.

The Women's Trade Union

League was established at a

convention of the

American Federation of

Labor in 1903. The two

female images on its

insignia represent the bond

between the mother and the

woman worker, the one

caring, the other strong.

The WTUL accepted the

primacy of women's

maternal obligations but

recognized the reality of

women's labor

involvement. Thus one of

the defining goals framed

by their clasped hands: to

guard the home. The other

two objectives were a

maximum of eight working

hours a day for women and

a wage sufficient to allow a

woman to support herself.

In 1896 women voted in only four statesWyoming, Colorado, Idaho, and Utah. The

West led the way in the campaign for

woman suffrage, partially because of

demographics, as in the case of Wyoming,

where only 16 votes were needed in the

state's tiny legislature to obtain passage of

the vote for women. This flag illustrates the

number of states where women voted.

In a fundamental shift, younger womencollegeeducated and self-supportingbegan refusing to be

hemmed in by the social constraints of women's

"separate sphere." The term feminism, just starting

to come into use, originally meant freedom for full

personal development.

Feminists were militantly pro-suffrage because

they considered themselves to be fully equal to

men, not a weaker sex entitled to men's protection.

Disputes led to the fracturing of the women's

movement, dividing the older generation of

progressives from their feminist successors who

prized gender equality higher than any social

benefit.

Urban Liberalism

A shift occurred in the center of gravity within

progressivism by 1910, as reflected in the career of

California Governor Hiram Johnson. A new strain

of progressive reform known as urban hiberalism

emerged from the partnership of urban middleclass

reformers, machine bosses, and the working class.

This new breed of urban middle-class reformers

pressured the state to take over the needs of the

urban poor.

Also confronting the bosses of the traditional

political machine were leftist parties like the

Socialist Party, which elected a congressman in

1910 and ran Eugene Debs as a presidential

candidate in 1912.

Urban liberalism was also driven by

nativism in the form of moral reform

movements and immigration restriction.

Although city machines adopted urban

liberalism, trade unions did not, and

rejected state attempts to interfere in labor

affairs.

As the major spokesmen for unions, Samuel

Gompers preached that workers should not seek

from government what they could accomplish by

their own economic power and self-help through a

process known as voluntarism, a creed that

weakened substantially during the progressive

years.

Over time as muckraking exposes revealed labor

exploitation, labor retreated from voluntarism by

embracing urban liberals' progressive legislation,

especially in the area of industrial hazards since

liability rules, based on common law, favored

employers and not injured workers.

But health insurance and unemployment

compensation, popular in Europe, conjured

up images of state-induced dependency

among the urban liberal reformers. These

major social reforms remained beyond the

reach of urban liberals in the Progressive

Era.

It would take a major depression during the

1930s to enable reformers to fashion a

permanent state solution to poverty.

After the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory

fire, some machine politicians led the

way in making laws and regulations in

order to improve labor conditions, but

it was clear that urban social problems

had become too big to be handled by

party machines.

The doors were the problem. Most were locked (to

keep the working girls from leaving early); the

few that were open became jammed by bodies as

the flames spread. When the fire trucks finally

came, the ladders were too short. Compared with

those caught inside, the girls who leapt to their

deaths were the lucky ones. "As I lookd up I saw a

love affair in the midst of all the horror," a

reporter wrote. A young man was helping girls

leap from a window. The fourt "put her arms

about him and kiss[ed] him. Then he held her out

into space and dropped her." He immediately

followed. "Thud-- dead, Thud-- dead...I saw his

face before they covered it...He was a real man.

He had done his best." -New York Tribune, March

26, 1911.

Former machine politicians such as Al Smith

and Robert Wagner formed ties with

progressives and became urban liberals—

advocates of active intervention by the state in

uplifting the laboring masses of America’s

cities.

The conversion of machine politicians was a

reaction to strong competition from a new

breed of middle-class progressive, skilled

urban reformers and the challenge from the

left by the Socialist Party.

The always pragmatic city machines adopted

urban liberalism without much ideological

struggle.

During the progressive years, the unions’ selfreliant “voluntarism” weakened substantially as

the labor movement came under attack by the

courts.

Judges granted injunctions to prohibit unions from

striking, and, in the Danbury Hatters case, the

Supreme Court’s decision rendered trade unions

vulnerable to antitrust suits.

After the American Federation of Labor’s “Bill of

Grievances” was rebuffed by Congress, unions

became more politically active.

Organized labor joined the battle for progressive

legislation and became its strongest advocate,

especially for workers’ compensation for

industrial accidents.

Between 1910 and 1917, all industrial states

enacted insurance laws covering on-the-job

injuries, yet health insurance and unemployment

compensation scarcely made it into the American

political agenda.

Old-age pensions met resistance because the

United States already had a pension system for

Civil War veterans and their survivors whose

enforcement was extremely lax. Easy access to

these veterans’ benefits prompted fears that a new

generation of workers could become dependent

upon state payments.

Not until a later generation experienced the Great

Depression would the country be ready for social

insurance.

Reforming Politics

Like the Mugwumps, progressive reformers

attacked the boss rule of the party system,

but did so more adeptly and more

aggressively, though their ideals of civic

betterment elbowed uneasily with their

politician’s drive for self-aggrandizement.

Progressive politicians, especially Robert

La Follette, felt that the key to reforming

party machines was to reclaim the power to

choose candidates. The progressives took

that power away from the bosses and gave it

to voters in a direct primary.

LaFaollette was transformed into a

political reformer when a Wisconsin

Republican boss attempted to bribe him in

1891 to influence a judge in a railway case.

As he described it in his Autobiography,

"Out of this awful ordeal came

understanding; and out of understanding

came resolution. I determined that the

power of this corrupt influence...should be

broken." This photograph captures him at

the top of his form, expounding his

progressive vision to a rapt audience of

Wisconsin citizens at an impromptu street

gathering.

Many progressive politicians-Albert B.

Cummins of Iowa, William S. U'Ren of

Oregon, and Hiram Johnson of Califomia,

all skillfully used the direct primary as the

stepping stone to political power; they

practiced a new kind of popular politics,

which was a more effective way to power

than the backroom techniques of machine

politicians.

Racism and Reform

At a time when black men were being driven

from politics in the South, their wives and

sisters got organized themselves and became an

alternative voice of black conscience. Sara

Iredell Fleetwood, superintendent of the

Freedman's Hospital Training School for

Nurses, founded the Colored Women's League

of Washington, D.C. in 1892 for purposes of

"racial uplift." This picture of the league was

taken on the steps of Frederick Douglass's

home in Anacostia, Washington. Mrs.

Fleetwood is seated at the far right, third row

from the bottom. The notations are by someone

seeking to identify the other members, a

modest effort to save for posterity these

women, mostly teachers, who did their best for

the good of the race.

This is a photograph of a history class at Hampton

Institute, a freedmen's school founded in 1868 in

Virginia where Booker T. Washington began his

career, and a model for many similar institutions

throughout the South. In a controversial

experiment in interracial education, Hampton also

began enrolling Native American students in

1878. Freed people regarded the educational

opportunities that Hampton and other such schools

provided them as immense privileges.

Nonetheless, such institutions, which were often

overseen by white benefactors, maintained strict

controls over their black students to train them in

the virtues of industriousness and self-discipline.

The young women were prepared for jobs as

teachers, but also as domestic servants and

industrial workers. In 1899,

Hampton's white trustees hired America's first

important female documentary photographer, Frances

Benjamin Johnston, who was white, to portray the

students' educational progress. Her photographs were

displayed at the Paris Exposition of 1900, where they

were much praised for both their artistic achievement

and their depiction of racial harmony. This image is

exceptionally rich for the diversity of its subjects and

the complexity of its content. A white female teacher

stands in the center among her female and male,

African American and Native American, students. All

are contemplating a Native American man in

ceremonial dress.

When all is said and done, we need to keep

in mind that a number of critical events in

African American history occurred during

the Progressive Era. Among these:

The primary originated in the South and by

1903 it was operating in seven southern states.

In the South, the primary was a white primary

that effectively barred African Americans from

political participation.

This exercise of white supremacy was justified

by labeling southern blacks as an "ignorant

electorate,» a racism accepted by leaders such

as Taft, who assured Southerners that "the

federal government has nothing to do with

social equality," and Wilson, who signaled that

he favored segregation of the u.S. civil service.

The foremost black leader of his day, Booker T.

Washington, spread a doctrine known as the

Atlanta Compromise; Washington thought that

black economic progress was the key to winning

political and civil rights.

Younger, educated blacks thought Washington

was conceding too much and became impatient

with his silence on segregation and violence

against blacks, such as the 1908 Springfield,

Illinois, race riot.

The Niagara Movement, led by William

Monroe Trotter and W. E. B. Du Bois,

defined the African American struggle for

rights: they proclaimed black pride, insisted

on full civic and political equality, and

resolutely rejected submissiveness.

Sympathetic white progressives fonned the

National Association for the Advancement

of Colored People (NAACP) in 1909.

The NAACP's national leadership was dominated

by white leadership. But the editor of The Crisis,

W. E. B. Du Bois, was an African American, and

he used that platform to demand equal rights for

blacks.

The National Urban League took the lead on

social welfare, uniting in 1911 the many agencies

serving black migrants arriving in northern cities.

In the South, welfare work was the province of

black women, who utilized the southern branches

of the National Association of Colored Women's

Clubs, which had started in 1896.

The Progressive Era

Part II

The Making of a Progressive President

Like many budding progressives, Theodore

Roosevelt was motivated by a high-minded

Christian upbringing, but he did not scorn power

and its uses.

During his term as governor of New York,

Roosevelt asserted his confidence in the

government's capacity to improve the lives of

people.

Roosevelt was chosen as William McKinley's

running mate by Republicans who hoped to

neutralize him, but he became president in 1901

after McKinley's assassination.

As president, Roosevelt adroitly used the

patronage powers of his office to gain control of

the Republican Party and displayed his activist

bent.

Roosevelt was troubled by the threat that big

business posed to competitive markets.

The mergers of individual businesses into trusts

decreased competition; bigger business meant

power to control markets. By 1910, 1 percent of

the nation's manufacturers accounted for 44

percent of the nation's industrial output

With the passage of the Sherman Antitrust Act of

1890, the federal government had enabled itself to

enforce firmly established common laws in cases

involving interstate commerce, but the power had

not been exercised.

In 1903 Roosevelt established the Bureau of

Corporations in order to investigate

business practices and to support the Justice

Department's capacity to mount antitrust

suits.

After winning the presidential election,

Roosevelt became the nation's trustbuster,

taking on corporations such as Standard Oil,

American Tobacco, and Du Pont

Theodore Roosevelt was motivated by a high-minded Christian

upbringing, but he did not scorn power and its uses.

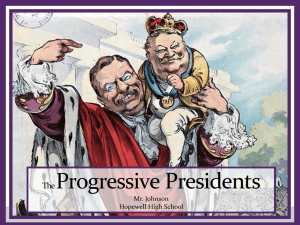

In this vivid cartoon from the

humor magazine Puck, Jack

(Theodore Roosevelt) has come

to slay the giants of Wall Street.

To the country, trust-busting took

on the mythic qualities of the

fairy tale-- with about the same

amount of awe for the fearsome

Wall Street giants and hope that

in the prowess of the intrepid

Roosevelt. J.P. Morgan is the

giant leering at front right.

In the Trans-Missouri decision of 1897, the

Supreme Court held that actions restraining or

monopolizing trade automatically violated the

Sherman Antitrust Act.

Roosevelt was not anti-business, and he did not

want the courts to punish "good" trusts, so he

exercised his presidential prerogative to decide

whether to prosecute a trust.

In 1904 U.S. Steel approached Roosevelt with a

deal-cooperation in exchange for preferential

treatment. This "gentlemen's agreement" appealed

to Roosevelt because it met his interest in

accommodating the modern industrial order while

maintaining his public image as slayer of the

trusts.

Roosevelt was convinced that the railroads' rates and

bookkeeping needed firmer oversight, so he pushed

through the Elkins Act (1903) and the Hepburn

Railway Act (1906), achieving a landmark expansion

of the government's regulatory powers over business.

Although Roosevelt was not a preservationist like John

Muir, he did advocate a conservationist position

regarding the West's natural resources. He believed in

efficient use and sustainability. He utilized the Public

Lands Commission (1903) to preside over the public

domain for purposes of efficient management.

An expanded Forest Service headed by expert forester

Gifford Pinchot helped Roosevelt to reverse a century

of heedless exploitation and imprint conservation on

the nation's public agenda.

Influenced by Upton Sinclair's The Jungle

(1906), Roosevelt authorized a federal

investigation into the stockyards. Soon

after, the Pure Food and Drug and Meat

Inspection Acts were passed and the Food

and Drug Administration was created.

During Roosevelt's campaign he called his

program the Square Deal, meaning that

when companies abused their corporate

power, the government would intercede to

assure Americans a fair arrangement.

Upton Sinclair was a desperately poor, young socialisthoping to remake the world

when he settled down in a tarpaper shack in Princeton Township and penned his

Great American Novel.

He called it "The Jungle," filled it with page after page of nauseating detail he had

researched about the meat-packing industry, and dropped it on an astonished

nation in 1906.

During Roosevelt's campaign he called his

program the Square Deal, meaning that

when companies abused their corporate

power, the government would intercede to

assure Americans a fair arrangement.

The power wielded by John D. Rockefeller and

the Standard Oil Company is captured in this

political cartoon, which appeared in the January

22, 1900, issue of The Verdict. Rockefeller is

pictured holding the White House and the

Treasury Department in the palm of his hand,

while in the background the U.S. Capitol has been

converted into an oil refinery. Standard Oil

epitomized the gigantic trusts that many feared

were threatening democracy in the Gilded Age.

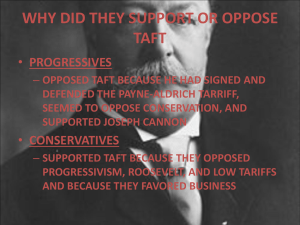

The Fracturing of Republican

Progressivism

William Howard Taft had served Roosevelt

loyally as governor-general of the Philippines and

as secretary of war. He was an avowed Square

Dealer, but he was not a progressive politician.

Taft won the election against William Jennings

Bryan in 1908 with a mandate to pick up where

Roosevelt had left off; however, this was not to

be.

William Howard Taft had

little aptitude for politics.

When Theodore Roosevelt

tapped him as his successor

in 1908, Taft had never

held an elected office. A

legalist by training and

temperament, Taft moved

congenially in the

conservative circles of the

Republican Party. His

actions dismayed

progressives and eventually

led Roosevelt to challenge

him for the presidency in

1912. The break with

Roosevelt saddened and

embittered Taft, who

heartily disliked the

presidency and was glad to

leave it.

William Howard Taft had served Roosevelt

loyally as governor-general of the

Philippines and as secretary of war. He was

an avowed Square Dealer, but he was not a

progressive politician.

Taft won the election against William

Jennings Bryan in 1908 with a mandate to

pick up where Roosevelt had left off;

however, this was not to be.

Progressives felt that Roosevelt had been too easy

on business, and with him no longer in the White

House, they intended to make up for lost time.

Although Taft had campaigned for tariff reform,

he ended up approving the protectionist PayneAldrich Tariff Act of 1909. which critics charged

sheltered eastern industry from foreign

competition.

After the Pinchot-Ballinger

affair. in which he fired Pinchot,

the first Chief of the United

States Forest Service, for

whistle-blowing on a conspiracy

to hand public land to a private

syndicate, the progressives saw

Taft as a friend of the "interests"

bent on plundering the nation's

resources.

Ballinger served as mayor of Seattle, then as

commissioner of the General Land Office from

1907–1908. In 1909, President William Howard

Taft appointed him Secretary of the Interior.

While Secretary, he was accused of having

interfered with investigation into the legality of

certain private coal-land claims in Alaska. After a

series of articles in Collier's Weekly that roused

the conservationists an investigation was

demanded. A congressional committee exonerated

Ballinger, but the questioning of committee

counsel Louis D. Brandeis made Ballinger's anticonservationism clear. He resigned in March,

1911

Galvanized by Taft's defection. the

reformers in the Republican Party became a

dissident faction. calling themselves the

“Insurgents."

Roosevelt knew that a party split would

benefit the Democrats, but he was driven to

set aside party loyalty when he clashed with

Taft over the question of trusts.

Unlike Roosevelt. Taft was unwilling to

pick and choose trusts for prosecution; he

instead relied on the letter of the Sherman

Act.

In the Standard Oil decision of 1911. the Supreme

Court once again asserted the rule of reason.

which meant that the courts, not the president.

would distinguish between good and bad trusts.

Taft.s attorney general brought suit against U.S.

Steel, basing the antimonopoly charges in part on

an acquisition approved by Roosevelt. Anxious to

reenter politics. Roosevelt could not ignore what

appeared to be a direct attack on his honor.

Roosevelt had made the case for what he called

the New Nationalism, its central tenet being that

human welfare had priority over property rights.

The government would become "the steward of

the public welfare."

Roosevelt added to his proposed program a

federal child labor law. regulation of labor

relations, a national minimum wage for

women. and. most radical perhaps.

proposals to curb the power of the courts

based on his insistence that they stood in the

way of reform.

Roosevelt was too reformist for party

regulars who handed Taft the Republican

presidential nomination for the 1912

election, so Roosevelt led his followers into

a new Progressive Party, nicknamed the

"Bull Moose" Party.

Woodrow Wilson and the New

Freedom

As Republicans battled among themselves,

Democrats made dramatic gains in 1910, taking

over the House of Representatives and capturing a

number of traditionally Republican governorships.

Governor of New Jersey, Woodrow Wilson,

compiled a sterling refonn record; he then went on

to win the Democratic presidential nomination in

1912.

. Wilson warned that the New Nationalism

represented a future of collectivism, whereas

his own New Freedom policy would preserve

political and economic liberty.

Wilson and Roosevelt differed over how

government should restrain private power.

Wilson won the election of 1912 because he

kept the traditional Democratic vote, while the

Republicans split betWeen Roosevelt and

Taft. Wilson's New Freedom did not receive a

clear mandate from the people in that he

received only 42 percent of the popular vote.

Wilson

encountered the

same dilemma that

confronted all

successful

progressives: how

to balance the

claims of moral

principle with the

unyielding

realities of

political life.

Progressives

prided themselves

on being realists

as well as

moralists.

However, the election did prove decisive in the

history of economic refonn; Wilson attacked the

problems of tariff and banking reform.

The Underwood Tariff Act of 1913 pared rates to

25 percent; the trust-dominated industries were

targeted to foster competition and reduce prices

for consumers.

The Federal Reserve Act of 1913 gave the nation a

banking system that was resistant to financial

panic, delegating financial functions to tWelve

district reserve banks. This strengthened the

banking system and placed a measure of restraint

on Wall Street.

To deal with the problem of corporate

power, the Clayton Antitrust Act of 1914

amended the Shennan Act; the Clayton

Act's definition of illegal practices was left

flexible to distinguish whether an action

stifled competition or created a monopoly.

The Federal Trade Commission was established in 1914, and it received broad powers

to investigate companies and issue "cease

and desist" orders against unfair trade

practices.

Steering a course between Taft's conservatism and

Roosevelt's radicalism, Wilson carved out a middle

way that brought to bear the powers of government

without threatening the constitutional order and

curbed abuse of corporate power without

threatening the capitalist system.

The labor vote had grown increasingly important

to the Democratic Party; before his second

campaign, Wilson championed a host of bills

beneficial to American workers-a federal child

labor law, the Adamson eight-hour law for railroad

workers, and the landmark Seamen's Act, which

eliminated age-old abuses of sailors aboard ship.

Wilson encountered the same dilemma that

confronted all successful progressives: how to

balance the claims of moral principle with the

unyielding realities of political life.

Progressives prided themselves on being

realists as well as moralists.

Progressives made presidential leadership

important again, they brought government

back into the nation's life, and they laid the

foundation for twentieth-century social and

economic policy.