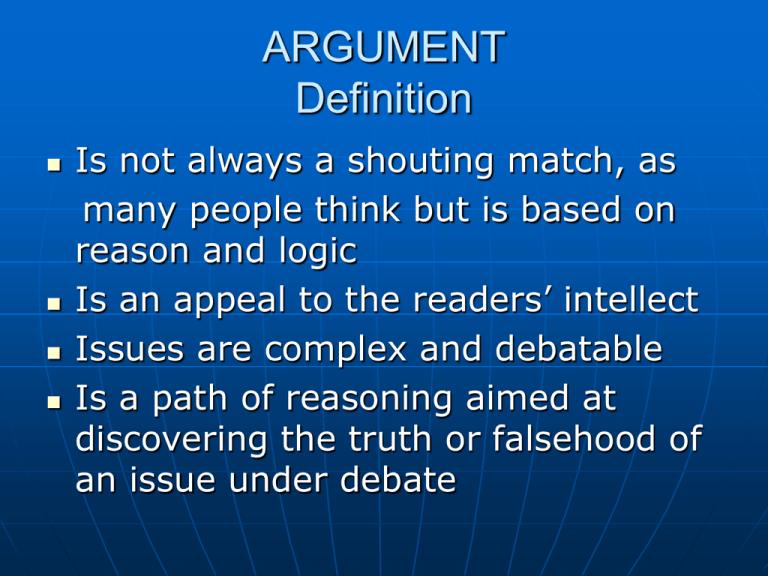

ARGUMENT

Definition

Is not always a shouting match, as

many people think but is based on

reason and logic

Is an appeal to the readers’ intellect

Issues are complex and debatable

Is a path of reasoning aimed at

discovering the truth or falsehood of

an issue under debate

ARGUMENT/PERSUASION

Important Points

Both are used together but they are

not the same thing.

Both are often blended.

Persuasion is a purpose for writing.

Argument is an appeal to the

readers’ intellect.

ARGUMENT/PERSUASION

Reasons to Persuade

1. To promote change.

Example: To have computers in

every classroom at Southeast

College.

2. To oppose a theory.

Example: Writing a history paper,

claiming that antislavery sentiment

was not the cause of the Civil War.

ARGUMENT/PERSUASION

Reasons to Persuade

3. To arouse sympathy.

Example: Passing more stringent laws against

people who abuse animals or for those who

drive while under the influence of alcohol.

4. To stimulate interest.

Example: Soliciting administrators and faculty

to implement a new course, such as Women’s

African-American Studies.

ARGUMENT/PERSUASION

Reasons to Persuade

5. To promote change

Example: To appeal to apartment

owners to provide more lighting or

on-site security or security gates

for tenants’ safety.

6. To provoke anger

Example: To arouse outrage against a

proposed tax hike or to get a petition to

abolish new legislation.

ARGUMENT/PERSUASION

Reasons to Persuade

7. To support a cause.

Example: To urge people to contribute

to different charity relief or fundraisers.

8. To urge people to take action.

Example: To get people to vote in an

upcoming election; to get people

involved in their local civic associations;

to urge people to write their elected

officials to get legislation passed or

repealed.

ARGUMENT/PERSUASION

Reasons to Persuade

9. To organize a public protest, using signs

and banners, where citizens censure

legislation.

10. To urge citizens to attend Town Hall

meetings in designated areas in

Houston for a progress report on

the many activities of our legislators

and the laws that passed or failed.

ARGUMENT/PERSUASION

Reasons to Persuade

11. To ask for a raise in salary.

12. To pay a bonus to employees who

have perfect attendance for a year

as an incentive not to miss work

or to contribute ideas that may

save a company time or money,

thereby improving efficiency.

ARGUMENT/PERSUASION

Obstacles

World events

Media “brainwashing”

Family influences

Fear of rejection by our peers

Being told our views are wrong, bad,

or immoral by so-called “experts.”

PERSUASION

Definition and Test for Success

Definition: To convince a person to think, act, or

behave in a certain way.

Test for success: If a person has changed his/

her views, actions, or behavior in favor of the

speaker or writer, then he/she has been persuaded.

Important: Even if a reader’s view has not been

changed, he/she may agree with the evidence but

not the conclusion.

ARGUMENT/PERSUASION

Appeals

Logical

Ethical

Emotional

ARGUMENT/PERSUASION

Definition of Appeals

Logical – based on facts, statistics, reasons

Example: A lawyer who is arguing a

case relies on a variety of evidence:

eyewitness testimony, experts, DNA,

visuals (charts, graphs, photos),

reenactments, audio tapes, and arguing

from precedent.

ARGUMENT/PERSUASION

Definition of Appeals

Ethical – comes from the writer’s character

Depends on one’s ability to convince readers of

his/her intelligence, commitment, and knowledge

of the issues.

Shows that a writer respects the readers’ point of

view.

Shows that a writer has done his/her homework.

Claims are not exaggerated or excessive.

ARGUMENT/PERSUASION

Definition of Appeals

Emotional – A message that appeals to the senses

and personal biases and prejudices of the reader.

Uses connotative language (words that elicit certain

feelings when a word is heard).

Example: “Corporate athleticism,” or increasing

profits, describes the business-minded attitude

that the NFL uses today. Question: What tone

does the writer have about the NFL?

ARGUMENT/PERSUASION

Elements Most Likely to Convince Readers

The writer’s competence

Quality of the reasoning (sound logic

and reasonable facts)

The degree to which writers appeal

to the readers’ self-interests (benefit

to readers)

ARGUMENT/PERSUASION

Types of Reasoning

Deductive – direct method (Hint:

(remember two d’s)

Moves from a broad generalization

(thesis) to specifics (examples, reasons,

evidence).

A conclusion follows from a set of

assertions or premises.

If the premises are true, then so is the

conclusion.

To challenge an argument, a reader has to

evaluate the premises.

ARGUMENT/PERSUASION

Types of Reasoning

Inductive – indirect method (Hint: Remember two

i’s.

Does not prove an argument is true.

Convinces readers the argument is probable.

Presents evidence logically by moving through an

assortment of data, which leads to a conclusion.

Used most often by lawyers, scientists,

detectives, and mystery writers.

ARGUMENT/PERSUASION

Assessing Evidence in Inductive Argument

Is it accurate? The facts must be correct.

Is it relevant? The evidence must be

connected to the point being made.

Is it representative? The conclusion must

be supported by evidence gathered from a

sample that accurately reflects the larger

population.

Is it sufficient? There must be enough

evidence to satisfy skeptical readers.

ARGUMENT/PERSUASION

Toulmin Method of Analyzing Arguments

Based on three facets:

Claim – a point or a thesis; an

assertion about a topic.

Grounds – reasons and evidence

(facts, statistics, anecdotes, and

expert opinion).

Warrants – assumptions or principles

that link the grounds to the claims.

ARGUMENT/PERSUASION

Toulmin Method of Analyzing an Argument

Statement: The death penalty should be

abolished because if it is allowed, innocent people

could be executed.

Part 1 – The independent clause is the thesis.

Part 2 – The dependent clause presents grounds

for the claims. (1) It is wrong to execute

innocent people and (2) it is impossible to be

completely sure of a person’s innocence or guilt.

ARGUMENT/PERSUASION

Types of Evidence for Claims

Using similes, metaphors, and imagery

Examples: “Our response to sexual predators must balance

the extent and intensity of the possible behavior with the

probability of its occurrence. An ex-prisoner likely to expose

himself on a crowded subway may be a risk we are willing to

assume. However, a prisoner with even a moderate

probability of sexual torture and murder is not. Such violence

is like a rock dropped into a calm pool—the concentric

circles spread even after the rock has sunk (a simile and

imagery).”

Source: “Sex Predators Can’t Be Saved” – Andrew Vachss

ARGUMENT/PERSUASION

Types of Evidence for Claims

Facts and statistics

Can be convincing.

Opponents can interpret same facts

and statistics differently.

Opponents may also cite different

facts and statistics to prove their

claims.

ARGUMENT/PERSUASION

Types of Evidence for Claims

Expert opinion – The views of authorities

in a given field is powerful evidence for a

claim. However, the expert must have the

proper credentials on the issue.

Example: According to Carl Blyth, an

expert on football safety, the head coach ‘s

attitude and leadership are the most

important factors in creating the balance to

win with the safety of the players.

ARGUMENT/PERSUASION

Types of Evidence for Claims

Anecdotes – brief narratives used as

illustrations to support a claim.

Example: court cases

Stories appeal to our emotions and

intellect.

Narratives can be very effective in

making an argument because they

personalize an experience.

ARGUMENT/PERSUASION

Titles

A title is compelling.

A title is usually a fragment.

A title suggests the subject matter.

A title may consist of a subtitle

followed by a major title.

Example: Affirmative Action:

Leveling the Playing Field for

Minorities or Using Quotas to Fill

Colleges and Jobs?

ARGUMENT/PERSUASION

Presenting Evidence

For a supportive audience: Place

the evidence from the most

important to the least important.

For a hostile audience – Place the

evidence from the least important to

the most important. In other words,

save your most compelling evidence

toward the end of the essay.

ARGUMENT/PERSUASION

Fallacy

Definition: Mistakes in logic; faulty

reasoning used to reach a conclusion.

Results of using a fallacy – Unclear

thinking; unclear logic; deceiving

readers.

ARGUMENT/PERSUASION

Common Logical Fallacies

False authority – presenting testimony of

an unqualified person to support a claim.

Example: “As the actor who plays Dr.

Fine on Emergency Room, I recommend this

weight-loss drug because … “ [Is an actor

qualified to judge the benefits and dangers

of a diet drug?]

ARGUMENT/PERSUASION

Strategies

Refutation – using contradictory

evidence to show that a position is false or

exposing inadequate reasoning to show that

a position cannot be true.

Defenses – clarifying a position; presenting

new arguments to support a position;

showing that criticisms of a position are

unreasonable or unconvincing.

ARGUMENT/PERSUASION

How to Avoid a Fallacy

Use enough examples to support an

assertion.

Qualify a broad statement about a

group of people or things.

Example: Use words like some,

most, a few, many, or a majority.

Cite examples that prove your

assertion.

ARGUMENT/PERSUASION

Common Logical Fallacies

Non sequitur – a conclusion that does

not logically follow from evidence presented

or one based on irrelevant evidence.

Example: Students who default on their

loans are irresponsible people. (Students

who default have reasons for their non

payment). We cannot conclude they are

irresponsible without modifying the

statement.

ARGUMENT/PERSUASION

Common Logical Fallacies

Hasty generalization – a form of improper

induction that draws a conclusion based on

insufficient evidence.

Example 1: No one can logically conclude

that one bad grade on an assignment is

indicative that a student will fail a course or

that a few bad teachers add up to a bad

school.

ARGUMENT/PERSUASION

Common Logical Fallacies

Example 2: Temperatures across the

United States last year exceeded the fiftyyear average by two degrees, thus proving

that global warming is a reality. [Is this

evidence enough to prove this broad

conclusion?]

ARGUMENT/PERSUASION

Common Logical Fallacies

Sweeping Generalization – a statement that

cannot adequately be supported no matter how

much evidence is supplied.

Example: Everyone should exercise. Most people

would agree, but not all people can exercise. Those

who are bedridden or wheelchair bound cannot

exercise their body, but they can exercise their

mind. Note: Be careful not to use absolutes

because they allow for NO exceptions!

ARGUMENT/PERSUASION

common Logical Fallacies

Guilt by association – discrediting a

person because of problems with

one’s associates.

Example: Martin’s friend is an ex-felon, so

Martin’s character is questionable. (Why

should Martin’s character be in question

because of his friend’s past mistakes with

the law?)

ARGUMENT/PERSUASION

Common Logical Fallacies

Stacking the deck – slanting evidence to

support a position.

Example: Nine out of ten doctors have

endorsed this product, so it is guaranteed to

work. On the surface, this statement sounds

convincing. [However, which doctors were

interviewed? Were they all hired by the company

that makes the product?}

ARGUMENT/PERSUASION

Common Logical Fallacies

False authority – presenting testimony

of an unqualified person to support a

claim.

Example: As the actor who plays Dr.

Fine on Emergency Room, I recommend this

weight-loss drug because … “{Is an actor

qualified to judge the benefits and dangers

of a diet drug?]

ARGUMENT/PERSUASION

Common Logical Fallacies

False analogy – a comparison in which a surface

similarity hides a significant difference.

Example: Governments and businesses both work

within a budget to accomplish their goals. Just as

businesses must focus on the “bottom line,”

so should government. [Is the goal of government

to make a profit or does it have more important

goals?]

ARGUMENT/PERSUASION

Common Logical Fallacies

Red herring – an argument that diverts

attention from the true issues by

concentrating on something irrelevant.

Example: Hemingway’s book Death in

the Afternoon is unsuccessful because

it glorifies the brutal sport of bullfighting.

[Why can’t a book about a brutal sport be

successful? The statement is irrelevant.]

ARGUMENT/PERSUASION

Common Logical Fallacies

Begging the question – circular

reasoning that assumes the truth of a

questionable opinion.

Example: The president’s poor relationship

with the military has weakened the armed

forces. [Does the president have a poor

relationship? If so, is it the only reason for

this so-called “weakened” relationship?]

ARGUMENT/PERSUASION

Common Logical Fallacies

Bandwagon – an argument that depends on going

along with the crowd on the false assumption that

truth is based on a “popular” view.

Example – Everybody knows that Hemingway is

preoccupied with the theme of death in his novels.

[Everybody implies there are no exceptions or

exclusions.] Is this statement too strong? Does it

need to be modified? If so, what are possible

revisions?

ARGUMENT/PERSUASION

Common Logical Fallacies

Ad hominem – a personal attack on

someone who disagrees with you

rather than on the person’s argument.

Example: The district attorney is a lazy

political hack, so naturally she opposes

streamlining the court system. [Even if she

usually support her party’s position, is she

automatically wrong to oppose this issue?

ARGUMENT/PERSUASION

Common Logical Fallacies

Circular reasoning – an argument that restates

the point rather than supporting it with evidence.

Example: The wealthy should pay more taxes

because taxes should be higher for people with

higher incomes. [Why should wealthy people pay

more taxes? The rest of the statement does not

answer this question—it merely restates the

position.]

ARGUMENT/PERSUASION

Common Logical Fallacies

Either/or fallacy – The idea that a

complicated issue can be resolved by

resorting to one of only two options when in

reality, there are additional issues to

consider.

Example: Either the state legislature will

raise taxes or our state’s economy will

deteriorate. [Is raising taxes the only way

to avoid a state deficit?]

ARGUMENT/PERSUASION

Common Logical Fallacies

Equivocation – when the meaning of a key word

or phrase shifts during an argument.

Example: It is not in the public interest for the

public to lose interest in politics. Although clever,

the shift in meaning of the term public interest

clouds an important issue: we need to VOTE and

support the candidates whom we believe are the

most qualified and will act in our behalf.

ARGUMENT/PERSUASION

Example of a Fallacy

Major premise – All embezzlers are

criminals.

Minor premise - All embezzlers are

people.

Conclusion – Therefore, all people are

embezzlers. [Is this true?] If not, how

should the conclusion be stated?

ARGUMENT/PERSUASION

Learning How to Argue

1. Figure out what the issue is. People

argue about issues, not topics. You

may want to turn your topic into a

problem by asking questions about it.

Does something indicate that all is not

the way it should be? If so, have they

changed for the worse? From what

perspectives—economic, social, political,

cultural, medical, or geographic can the

argument be made?

ARGUMENT/PERSUASION

Learning How to Argue

2. Develop a reasonable position

that negotiates differences. As a writer

you want readers to trust your judgment.

Conducting research will make you

informed; reading other people’s views and

thinking critically about them will enhance

the quality and scope of your argument.

ARGUMENT/PERSUASION

Learning How to Argue

Find out what others have to say

about the issue; negotiate the

differences between your position

and theirs.

Pay attention to your areas of

disagreement but acknowledge

areas of agreement as well.

ARGUMENT/PERSUASION

Learning How to Argue

Always remember that two views on the

same issue can be similar but not

identical or different but not completely

opposite.

Avoid language that may promote

prejudice or fear.

Furthermore, avoid misrepresentations of

others, ideas, and personal attacks on

someone’s character.

ARGUMENT/PERSUASION

Learning How to Argue

Write arguments to open minds,

not offend.

3. Make a strong claim.

Advancing a strong debatable thesis

(claim) on a topic of interest is the

key to writing a successful

argument.

ARGUMENT/PERSUASION

Learning How to Argue

Keep in mind, though, that as you

think, write, and learn about your

topic, you will develop, clarify, and

sometimes entirely change your

views.

Think of yourself as a potter working

with clay. Your thesis is still forming

as you work on the topic.

ARGUMENT/PERSUASION

Learning How to Argue

Personal feeling on a debatable issue

I (feel, think, believe) that professional football

players are treated poorly.

Accepted fact, not a debatable issue

Many players in the NFL are injured each year.

Debatable Thesis

Current NFL regulations are not enough to protect

players from suffering the hardships caused by

game-related injuries.

ARGUMENT/PERSUASION

Learning How to Argue

4. Support and develop your

claim

Think of an argument as a dialogue

between the writer and the readers.

A well-developed argument includes

a variety of evidence.

Pay attention counterarguments

(claims that do not support your

position).

ARGUMENT/PERSUASION

Using Counterarguments

Qualify your thesis in light of the

counterarguments by including a

word such as most, some, usually,

likely, or may.

Example: Although many people—

fans and non-fans alike—understand

that football is a dangerous sport, few

realize just how hard some NFL players

have it.

ARGUMENT/PERSUASION

Using Counterarguments

Add to the thesis a statement of the

conditions for or exceptions to your

position.

Example: The NFL pension plan is

unfair to players who have fewer

than five years in the league. The

plan is unfair to certain players, not

all of them.

ARGUMENT/PERSUASION

Using Counterarguments

Choose all the counterarguments you

can find and plan to refute their

truth or importance in your paper.

Example: Biglione, for example, refutes

the counterargument that the NFL has a

good pension plan for its players.

ARGUMENT/PERSUASION

Learning How to Argue

5. Create an outline that includes a

linked set of reasons.

An introduction to the topic and the

debatable issue.

A thesis stating your position on the

issue.

A point-by-point account of the reasons

for your position, including

the evidence (facts, statistics, a study,

expert opinion) you will use to support

each major reason.

ARGUMENT/PERSUASION

Using Counterarguments

A fair presentation and refutation of

the counterarguments to your thesis.

A response to the “So what?”

question. Why does your argument

matter?

ARGUMENT/PERSUASION

Learning How to Argue

6. Appeal to your audience

Share common ground with your

audience.

Use all three appeals (logos (logic),

ethos (character), and pathos

(emotion).

7. Emphasize your commitment to dialogue

in the introduction by sharing a concern

with your audience.

8. Conclude by restating your position and

emphasizing its importance.

ARGUMENT/PERSUASION

Learning How to Argue

Remind readers of your thesis.

The version of your thesis presented in

your introduction should be more

complex and qualified than the

introduction to encourage readers to

see the importance of your argument.

Even if readers do not agree with you,

they should be aware of the importance

of both the issue and the argument.

ARGUMENT/PERSUASION

Learning How to Argue

10. Reexamine your reasoning.

Have you given a sufficient number of

reasons to support your thesis, or should

you add more?

Have you made any mistakes in logic

(a fallacy)?

Have you clearly and adequately

developed each reason you have

presented in support of your thesis?

ARGUMENT/PERSUASION

Potential Traps to Avoid

1. Don’t claim too much. You cannot

state the solution you propose will

solve all the problems; for example,

implying that legalizing drugs would

alleviate all drug-related crimes. It

would prevent some crimes, but it would

create other problems. State the ideas

that you think are worth considering, or

suggest a new approach.

ARGUMENT/PERSUASION

Potential Traps to Avoid

2. Don’t oversimplify complex issues.

When an issue is serious enough to debate, it is

complicated, and the issues are difficult to solve.

Trying to make an issue simpler by stating there

is an “obvious” solution undermines your

credibility. Instead, acknowledge the matter is

difficult to solve but suggest there are some

possible solutions.

ARGUMENT/PERSUASION

Potential Traps to Avoid

3. Support arguments with concrete

evidence and specific proposals, not

with generalizations and commonly held

beliefs. Because your argument is likely to

be viewed by a skeptical audience, readers will

expect you to demonstrate your case

convincingly. Moreover, they will not be

persuaded by opinion alone. You can only

expect to hold their attention and get respect if

you teach them something in your argument by

presenting an old problem in a new way.

SOURCES

The New McGraw-Hill Handbook –

Maimon, Peritz, and Yancey.

The Wadsworth Handbook – Kirszner

and Mandell.