Meditations on First Philosophy

advertisement

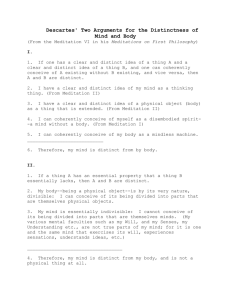

Meditations on First Philosophy Summary of Descartes’ arguments Meditation I • 1. A firm foundation for the sciences requires a truth that is absolutely certain; for this purpose, I will reject all my beliefs for which there is even a possibility of doubt, and whatever truths are left will be absolutely certain. I continued • 2. To this end it is not necessary to go through all my beliefs individually, since they are all based on a more fundamental belief. If there is any reason to doubt this foundation belief, then all the beliefs based on it are equally doubtful. Meditation I continued • 3. All my beliefs about the world are based on the fundamental belief that the senses tell me the truth. But this belief is not absolutely certain. It is at least possible that everything my senses tell me is an illusion created by a powerful being. Therefore, there is some reason to doubt my foundation belief, and thus all my beliefs about the world are doubtful; none of them can serve as the foundation for science. Meditation II • 1. If all my beliefs about the world are doubtful, is there any truth which can be absolutely certain? Yes. Even if all of my experience is an illusion, it cannot be doubted that the experience is taking place. And this means that I, the experiencer, must exist. 2. Since the only evidence I have that I exist is that I am thinking (experiencing), then it is also absolutely certain that I am a thing that thinks (experiences), that is, a mind. Meditation II continued • 3. Since I am not certain (yet) that the physical world (including my body) exists, but I am certain that I exist, it follows that I am not my body. Therefore, I know with certainty that I am only a mind. 4. I am much more certain of my mind's existence than my body's. It might seem that in fact we know physical things through the senses with greater certainty than we know something intangible like the mind. Meditation II continued • But the wax experiment demonstrates that the senses themselves know nothing, and that only the intellect truly knows physical things. It follows that the mind itself is known with greater certainty than anything that we know through the senses. Meditation III • 1. Every idea must be caused, and the cause must be as real as the idea. If I have any idea of which I cannot be the cause, then something besides me must exist. 2. All ideas of material reality could have their origin within me. But the idea of God, an infinite and perfect being, could not have originated from within me, since I am finite and imperfect. III continued • 3. I have an idea of God, and it can only have been caused by God. • 4. Therefore God exists. Meditation IV • 1. Only an imperfect (less than perfectly good) being could practice deliberate deception. Therefore, God is no deceiver. 2. Since my faculty of judgment comes from God, I can make no mistake as long as I use it properly. But it is not an infinite faculty; I make mistakes when I judge things that I don't really know. IV continued • 3. God also gave me free will, which is infinite and therefore extends beyond my finite intellect. This is why it is possible to deceive myself: I am free to jump to conclusions or to proclaim as knowledge things that I don't know with absolute certainty. IV continued • 4. I therefore know now that if I know something with absolute certainty (clearly and distinctly), then I cannot be mistaken, because God is no deceiver. The correct way to proceed is to avoid mistakes and limit my claims to knowledge to those things I know clearly and distinctly. Meditation V • 1. Now I want to find what can be known for certain about material objects. Before deciding whether they exist outside me, I know that my ideas of them consist of shape, size, motion, etc. I also know that by thinking about these attributes I can discover certain facts that are necessarily true about them (the truths of geometry, for example). 2. I do not invent ideas such as geometrical shapes, nor do I get them from sensory experience. Proof of this is the fact that I can discover geometrical truths about figures which I cannot imagine. V continued • 3. Just as, by thinking about my ideas of geometrical shapes, I can discover truths that necessarily belong to them, I can do the same with God. I have a clear and distinct idea of a perfect being. Perfect = lacking nothing. I cannot conceive of a being that is perfect but lacks existence. Therefore, existence necessarily belongs to God. V continued • 4. This doesn't mean that my thinking of something makes it exist. If I conceive of a triangle, I must conceive of a figure whose angles equal two right angles. But it doesn't follow that the triangle must exist. But God is different. God, being perfect, is the one being to whom existence must belong. Thus, when I conceive of God, I must conceive of a being that exists. V continued • 5. Because God, being perfect, is not a deceiver, I know that once I have perceived something clearly and distinctly to be true, it will remain true, even if later I forget the reasoning that led me to that conclusion. I could not have this certainty about anything if I did not know God. Meditation VI • 1. All that is left is to determine whether material objects exist with certainty. I know that the abstract shapes representing them are real, since I perceive them clearly and distinctly in geometry. 2. Furthermore, I have a faculty of imagination, by which I can conceive of material objects, and which is different from my intellect. That it is different is proven by my ability to do geometry with unimaginable figures. Only intellect is necessary for my existence. VI continued • 3. The most likely explanation for the existence of my faculty of imagination is that my mind is joined with a body that has sense organs. This is even more likely in the case of the faculty of sensation. 4. It formerly seemed that all my knowledge of objects came through the senses, that their ideas originated from and corresponded to objects outside me. It also seemed that my body belonged especially to me, although I did not understand the apparent connection between mind and body. VI continued • 5. Then I found it possible to doubt everything. Now I am in the process of systematically removing doubts where certainty exists. 6. Now that I know God can create anything just as I apprehend it, the distinctness of two things in my mind is sufficient to conclude that they really are distinct. Thus I know I exist, I am a thinking thing, and although I may possess a body, "it is certain that this I is entirely and absolutely distinct from my body, and can exist without it." VI continued • 7. My faculty of sensing is passive and thus presupposes a faculty of causing sensation, which cannot be within me, since some ideas come to me without my cooperation and even against my will; it therefore belongs to something else. This is either a body or God. But since God is not a deceiver, he doesn't plant these ideas directly in me (doesn't make me believe in a nonexistent world). Therefore corporeal things exist. My senses might mislead me about the details, but I know at least that the ideas that I clearly and distinctly understand--geometrical properties-belong to these bodies. VI continued • 8. Nature is God's order; thus it has truth to teach me. For example, that I am present to my body in a more intimate way than a pilot in a ship. And that there are other bodies around me that affect me in various ways, that should be pursued or avoided; the senses thus act to preserve and maintain the body. VI continued • 9. But I also make some judgments on my own that are not justified by nature's teachings, particularly in assuming objects and their qualities to be exactly as my senses report them, that sense qualities reside in them, etc. It is the fault of my judgment that I use sense perception as a direct apprehension of the essences of external bodies; there is nothing inherently deceptive about sensation. VI continued • 10. Another problem is the misleading signals I sometimes get from my own body, which induce me to commit errors. A body with edema, for example, will have an inclination to drink, when in fact this is something it ought to avoid. How can God permit this? 11. The body is divisible, the mind is not. Further, the mind gets impressions from the parts of the body not immediately, but via the brain. VI continued • 12. By using more than one sense, and memory, I can avoid errors of the senses of this kind. So I should get rid of the excessive doubts I started with, especially those premised on dreaming, since I can easily distinguish dreaming from waking by the continuity of the latter. I can trust the truth of my ideas as long as my senses, memory, and understanding are all consistent with one another. Close the book Questions??