What is an argument? PP

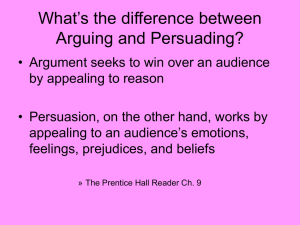

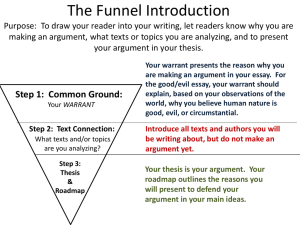

advertisement

What is an argument? Some people say that EVERYTHING is an argument. So – let’s see. If that’s so, what is the argument here? Every argument starts with a question. So – what questions does this text inspire? SOAPS is one way to start thinking about how to argue. S = What is the subject? O = What is the occasion? A = Who is the audience? P = What is the purpose? S = Who is the speaker? The questions can be a lot more complex, as can the answers. Can you see how important it is to understand this basic formula before you start to argue? Every text you analyze relies on this formula, and every text you create will rely on this formula as well. It is also important to consider the tone. Tone is the author’s attitude towards the subject. Tone can always be identified by using an adjective. Sometimes the tone will vary throughout the argument. You might use a few. Tone is connected to audience. What effect are you going for? Informative? Sarcastic? Conversational? Dismissive? Scathing? Once you have identified your SOAPSTone, begin to form a question. • The question should begin with How or Why, but it doesn’t have to as long as the answers are complex. If you can answer your question with one word, it’s a bad question. How can facial hair define your personality? Why are beards such a thing? Do I care? You should. By carefully and respectfully reading the viewpoints of others and considering a range of ideas on an issue, you can develop a clearer understanding of your own beliefs – a necessary foundation to creating effective arguments. You might not always have to write one, but you will be making arguments forever. Please, please, please buy me a new Kia Soul! Please, please, please marry me! I hate beards . . . Argument is not about partisanship or polarization. Argument is persuasive discourse – a coherent movement from a claim to a conclusion. It’s a way of better understanding other people’s ideas as well as your own. . . . but I sort of get why some people might really, really like them. This is my claim, and I’m sticking to it. • Every argument has a claim that states the argument’s main idea or position. It’s not just a topic (beards). It has to be arguable. (Beards are weird). It has to be a position that some people might disagree with and others might agree with. • It has to be stated as a complete sentence. Hmm. I wonder who else has been thinking about beards? A writer can’t develop a strong claim without exploring a topic through reading about it, discussing it with others, brainstorming, taking notes, and rethinking. Claims of Fact • Claims of fact assert whether something is true or not. Facts become arguable when they are questioned, whey they raise controversy, when they challenge people’s beliefs. Very often facts are a matter of interpretation. Sometimes new facts call into question old facts. Sometimes arguments of fact challenge stereotypes or social beliefs. People who wear beards are much more welladjusted than those who don’t. Claims of Value • Claims of value are the most common type. They argue whether something is good or bad, right are wrong, desirable or undesirable. They can be personal judgments based on taste, or they can be more objective evaluations based on external criteria. To develop this type of claim, you must establish specific criteria and then show to what extent your subject meets your criteria. A face without a beard is like a vanilla ice cream cone without sprinkles – boring and bland. Claims of Policy • Claims of policy propose making a change. The argument generally begins with a definition of the problem (which might be a claim of fact), explains why it is a problem (which might be a claim of value), and then explains the change that needs to happen. It may call for direct action to take place or just ask for a change of attitude. Because beards harbor disease and are unattractive besides, no man who wants to get married should ever grow a beard. Thesis Time • To develop a claim into a thesis statement, you have to be more specific about what you intend to argue. A thesis is usually stated as one sentence in the introduction of your essay. It should preview the essay by encapsulating in clear language the main point or points you intend to make. • There are 3 kinds. Closed Thesis A closed thesis is a statement of the main idea of the argument that also previews the major points of the essay. It limits the number of points. A closed thesis often includes the word because. This type helps you organize and makes sure you cover the key points. Beards should be banned because they are bizarre, old-fashioned, and much too large to be sanitary. Open Thesis If you have an essay with five or more points, an open thesis is better. A open thesis doesn’t list all the points. Beards are the bane of the universe. Counterargument Thesis This thesis is a variant in which a summary of a counterargument qualified by although or but precedes the writer’s opinion. This can make your argument appear to be stronger and more reasonable. Although Mr. Belluzzi would say only Italians should wear beards, many pumpkins would disagree. Now it’s time to gather evidence. • What evidence to present, how much is necessary, and how to present it are all rhetorical choices guided by an understanding of the audience. • Evidence should be relevant, accurate, and sufficient. You must quote sources accurately. Use enough credible sources so that people will actually believe you. Type 1: First-Hand Evidence • First-hand evidence is something you know, whether from personal experience, anecdotes you’ve heard from others, observations, or your general knowledge of events. Personal Experience • The is the most common type of first-hand. • This adds a human element and can be an effective way to appeal to pathos. • This is good to use in an introduction or a conclusion. • This can make an abstract concept more concrete. • This works best if you are an insider. My father hated beards, and so my brother has never grown one. I’ve never had a boyfriend with a beard, either. Anecdotes • Use a story you heard or observed about someone else. • This type can appeal to pathos. When I was in college, all the boys in one fraternity decided to grow beards to see whose would grow the fastest. Current Events • Staying abreast of what is happening locally, nationally, and globally ensures a store of information that can be used as evidence. • Seek out multiple perspectives. • Beware of bias. Brooklyn hipsters have some of the best beards of the 21st century. Type 2: Second-Hand Evidence • Second-hand evidence is accessed through research, reading, and investigation. • It includes factual and historical information, expert opinion, and quantitative data. • Anytime you cite what someone else knows, not what you know, you are using secondhand knowledge. • The main appeal is to logos. Historical Information • This includes verifiable facts that a writer knows from research. • This can provide background and context to current debates. • It can establish ethos because it shows the writer cares enough to research. • Be brief with this information – it can overwhelm your own argument otherwise. Abraham Lincoln’s beard is one of the more famous beards. Expert Opinion • An expert is someone who has published research on a topic or whose job provides specialized knowledge. • Your source must be credible if you want to add weight to your own argument. Professor Beardsley has often remarked on his own beard, which he has been growing since he was twelve. Quantitative Evidence • This includes things that can be represented in numbers – statistics, surveys, polls, etc. • This appeals to logos, mainly. I learned that 25% of men who wear beards like plaid flannel shirts. Logical Fallacies • This is a failure to make a logical connections between the claim and the evidence used to support the claim. • They can be accidental or manipulative and deceitful. • Look for these in your own arguments AND the arguments of others. • It’s more important to find them than to label them. Fallacies of Relevance • Red herring – the speaker skips to a new topic in order to avoid the old one “Yes, I know some people hate beards, but what are we going to do about Ebola.” • Ad hominem – the speaker attacks the character of the other speaker rather than the argument “Don’t believe anything you hear from anyone who wears a beard.” • Faulty analogy – the dissimilarities outweigh the similarities “I think I’ll buy this watch – Wolverine wears one, and his beard is reliably cool.” • Band wagon – the evidence boils down to “everybody’s doing it” “If you’re cool, you’ll grow some facial hair – everybody’s doing it in Brooklyn.” Fallacies of Accuracy • Straw man – the speaker chooses a deliberately poor or oversimplified example in order to ridicule the opponent “People who don’t like beards must hate Santa Claus.” • Either/or – the speaker presents two extreme options as the only possible choices “If you don’t love beards, you must hate men.” • Post hoc ergo proctor sum – claims that something is a cause just because it happened earlier “My father began to grow a beard soon after he began mowing his own lawn.” • Appeal to false authority – occurs when someone who has no expertise to speak on an issue is cited as an authority “Let’s ask Hillary Clinton what she thinks about beards.” Fallacies of Insufficiency • Hasty generalization – there isn’t enough evidence to support a particular conclusion “Shaving is just another unnecessary and painful procedure. The people who invented shaving were sadists.” • Circular reasoning – this repeats the claim as a way to provide evidence “You can’t hate my beard – it’s a great beard.” ID the Logical Fallacy • What’s the problem? All my friends have a curfew of midnight! • A person who is honest will not steal, so my client, an honest person, clearly is not guilty of theft. • Her economic plan is impressive, but remember: this is a woman who spent six weeks in the Betty Ford clinic getting treatment for alcoholism. More • Since Mayor Perry has been in office, our city budget has had a balanced budget; if he were governor, the state budget will finally be balanced. • It we outlaw guns, only outlaws will have guns. • Smoking is dangerous because it is harmful to you health. More • He was last year’s MVP, and he drives a Volvo. That must be a great car. • A national study of grades 6-8 shows that test scores went down last year and absenteeism was high; this generation is going to the dogs. Shapes Classical Inductive Deductive Toulmin Classical Organization • Introduce your topic. It’s all about the ethos. • Include some additional background information and state your thesis. It’s all about the pathos. • Discuss and analyze each of the thesis subtopics. Use your sources. It’s all about the logos. • Present the counterargument. Logos, again. • Conclude by answering the question, “So what?” It’s all about the pathos (with a bit of ethos). Jazz hands at the end are always welcome. Inductive Organization • Most of us use this type every day, especially when we write about science. • Write your essay using reasons, one after the other, to support your main point. Use anecdotes and expert opinion. • This type of argument will lead to a probability, not certainty. • This moves from particulars to universals. So – jazz hands at the end as you reveal your inference. Deductive Organization • Take a universal truth and apply it to a specific case. • The syllogism form works well here. You’ll have a major point to make and then a minor one. Both must be true. • Then you’ll come to a conclusion. Syllogism Format • Major Premise: Exercise contributes to better health. • Minor Premise: Yoga is a type of exercise. • Conclusion: Yoga contributes to better health. • Beware of a questionable premise – Major – Celebrities are role models. Minor – Lindsey Lohan is a celebrity. Conclusion -- Lindsey Lohan is a role model. Toulmin Organizaton – Comes with its own thesis! • This type of argument uncovers the various assumptions that underlie arguments, especially abstract ones. • The following template will help you organize a Toulmin thesis and argument. • Because (EVIDENCE), therefore (CLAIM) since (ASSUMPTION) on account of (BACKING) unless (RESERVATION). Because it’s raining, I should take my umbrella since an umbrella will keep me dry on account of it being waterproof unless there’s a hole in it. • Usually you have to revise these because they’re awkward at first. Visual Text Analysis • Where did the visual first appear? Who is the audience? Who is the speaker? Does the person have political or organizational affiliations that we need to know about? • What do you notice first? Where is your eye drawn? What is your overall first impression? • What topic does the visual address or raise? Does the visual make a claim about the topic? More Visual • Does the text tell a story? What’s the point? • What emotions does the text evoke? How do color and light and shadow contribute to the emotion? • Are the figures realistic or distorted? What is the effect? • Are any of the images visual allusions that would evoke memories or emotions? More Visual • What cultural values are viewers likely to bring to the images? • What claim does the visual make about the issue it addresses? Synthesis – 1st Step • After you have gathered your evidence, identify the issues and recognize the complexities. You want to aim for a compelling argument that leaves the reader thinking and questioning. You have to acknowledge that the issue is complex with no easy solutions, one that provides a variety of valid perspectives. You want to present a reasonable idea in a reasonable voice. Synthesis 2nd Step • Formulate your own FINAL position. Ask all the big questions you can think of after you have gathered your evidence. You don’t want to present a one-sided argument. Now you are ready to formulate your final thesis. You should use one of the three types. Synthesis 3rd Step • Frame your quotations. It’s important not to simply summarize or paraphrase the sources. You need to use the sources to strength your own arguments. Include a sentence or two of explanation and commentary with each quote. This should be a lead-in sentence (so you audience knows what to look for) and commentary after the source content to remind the audience of your point and how the quote or paraphrase reinforces it. Make sure to cite any ideas that are not your own. Synthesis 4th Step • Integrate your quotations. You want the transition from your own voice to others’ words and ideas to be smooth and natural. The most effective way to do this is to incorporate the quotes into your own sentences. The reader can more easily follow your ideas this way and see the sources in the context of your argument. Be sure that the result is grammatically correct and syntactically fluent. Synthesis 5th Step • Cite your sources. You need to cite paraphrases as well as direct quotes. An elegant way to cite is to also include the author and title in the lead-in sentence. You will need to include also parenthetical citations and a Works Cited page. NoodleTools and MLA • Since you will be using NoodleTools to do your research, citing sources and creating the Works Cited page will be easy. You can access NoodleTools through the school’s library page on Schoolwires. Grammar Rules: Errors in these 3 categories are considered the most egregious by college professors. • The FANBOYS Rule S+V, conjunction S+V. FANBOYS = for, and, not, but, or, yet, so I love beards, but I don’t like mustaches. Semi-Colons Are Strong • The Semicolon Rule S=V; S+V I love beards; I hate mustaches. Clauses Have Subjects and Verbs • The Subordinate Clause Rule Adverb: Until I met him, I hated beards. I hated beards until I met him. Adjective: People who hate beards aren’t cool.