The Chemical Senses

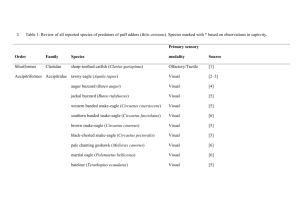

advertisement

The Chemical Senses Gustation and Olfaction The peripheral taste system • • • Primary receptors: about 4000 taste buds in tongue and oral cavity Each taste bud contains 30-100 receptor cells (modified epithelial cells) together with supporting cells and stem cells. Classically, 4 primary flavor submodalities can be identified in humans: sweet, salty, sour and bitter. We presently believe that for the sweet and bitter submodalities, there is a small number of receptor proteins which have very wide ability to recognize stimulant molecules. This map of submodality specific tastebuds on the tongue in many textbooks… …is BS, or at least a misrepresentation of how the system works. Unfortunately, a great many texts still include it. Actually, all taste buds are more or less sensitive to all of the classic submodalities, so taste receptors are not labeled lines. There are additional submodalities • In humans, a fifth submodality, called umami (Japanese for “yummy”) is stimulated by amino acids – this is why monosodium glutamate is an effective flavor enhancer • Recently, a fat submodality has been proposed for humans. • At least some animals (rats, for example), have a water submodality. Central pathways for gustatory information The key points here: Taste info passes from primary afferents in the tongue and pharynx along cranial nerves VII, IX and X to the gustatory nuclei of the brainstem. Individual axons in these pathways typically show some responsiveness to all 4 classic submodalities, but typically respond best to one of the 4. From the brainstem nuclei the information passes to the thalamus and then to the tongue-mouth area of the primary somatosensory cortical map. Note that this is a non-decussating pathway. The Olfactory System Olfactory Transduction • 1o olfactory receptors are neurons • In most mammals there are two locations for primary receptors – the main olfactory area, which serves for odors not related to social interactions, and the vomeronasal organ, which specializes in pheromones. • Some humans have a vomeronasal organ or two, but it seems largely non-functional. From the olfactory epithelium to the olfactory bulb The number of olfactory receptor proteins coded in the mammalian genome is typically very large (about 30,000 genes or about 10% of the total genome of the rat, for example). There are several million primary receptor cells in a typical mammal, and it seems probable that each receptor cell expresses one or only a few types of receptor protein. Glomeruli are sites of synaptic connection between receptor cells and 2nd order (mitral) cells. Each glomerulus contains dendrites of about 25 mitral cells and receives input from about 25,000 receptor cells. The axons of mitral cells and tufted cells enter the olfactory nerve. ( periglomerular cells and granule cells are local circuit neurons and do not project to the rest of the brain.) The basic circuit between the olfactory receptors and the olfactory bulb How is odor information sorted out by the N.S? • The concept of primary odors (i.e. a small set of odor submodalities) is not useful – there are too many odors, and almost all natural odor stimuli are chemical mixtures. Discriminating such mixtures is apparently of selective advantage. For example, a trained dog can distinguish between an apparently unlimited number of individual humans. • Receptor neurons that express particular odorant molecules send their axons to distinct subsets of glomeruli, so when the animal is presented with a particular odor, a corresponding set of glomeruli will respond – if the brain sees the pattern of glomerulus activation as a “picture” of a particular odor, a large number of different odors could be represented. The olfactory bulb is a map of the olfactory epithelium The olfactory bulb carries out a computational analysis of odor stimuli This olfactory bulb of a living mouse has been stained with a dye that reveals all of the superficial glomeruli. If the animal were stimulated with a sample of its home cage air, approximately 6 glomeruli would become active. The odor of camphor lights up about the same number of glomeruli, but they are at different locations from the ones reactive to cage air. However, as far as we know now, there is no cortical map of glomerular locations. Olfactory cortical cells gain specificity for particular molecules by integrating input from glomeruli that recognize different features Olfactory pathways go to both the cortex and the limbic system Main olfactory epithelium Vomeronasal organ Olfactory bulb Accessory olfactory bulb Thalamus Orbitofrontal cortex Limbic system In humans, the main olfactory pathway branches to go to the cortex and the limbic system To cortex To limbic system Impacts of odor information on behavior and physiology in humans • Exposure to the odor of males can make female menstrual cycles more regular • Pheromonal communication between women living in close contact can cause menstrual cycles to become synchronized • A pheromone apparently produced by all individuals promotes friendliness and social behavior. The vomeronasal organ is part of a separate path for olfactory information to the limbic system in non-human mammals Pheromonal Communication in non-human animals • Female estrus pheromones elicit male sexual behavior; male pheromones facilitate female receptiveness. • Urine from an unfamiliar male mouse causes pregnant female mice to abort their pregnancies and initiate ovulation • Individual-specific odors are important in mate choice in rodents – because they carry information about how closely related the choice animal is to the chooser.