Rutherford Scattering - Department of Physics, HKU

advertisement

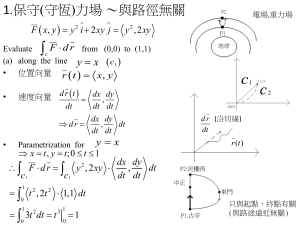

Nuclear Systematics and Rutherford scattering Terminology • • • • • • • • • • • Atomic number (Z) is the number of protons in the nucleus of an atom, and also the number of electrons in a neutral atom Nucleon: proton (Z) or neutron (N) Nuclide: nucleus uniquely specified by the values of N & Z Mass number (A) is the total number of nucleons in a nucleus (A=Z+N) Isotopes: nuclides with the same protons (Z) e.g. 235U and 238U Isotones: nuclides with the same neutrons (N) e.g. 2H (d) and 3He Isobars: nuclides with the same A Atomic mass unit (u): one-twelfth of the mass of a neutral atom of 12C (six protons, six neutrons, and six electrons). 1 u = 1.66 x 10–27 kg = 931.5 MeV/c2 Atomic mass is the mass of a neutral atom and includes the masses of protons, neutrons, and electrons as well as all the binding energy. Nuclear mass is the mass of the nucleus and includes the masses of the protons and neutrons as well as the nuclear binding energy, but does not include the mass of the atomic electrons or electronic binding energy. Radioisotopes: members of a family of unstable nuclides with a common value of Z Units • • • SI units are fine for macroscopic objects like footballs but are very inconvenient for nuclei and particles use natural units. Energy: 1 eV = energy gained by electron in being accelerated by 1V. Mass: MeV/c2 (or GeV/c2) 1 MeV/c2 = 1.78X10-30 kg. 1 GeV/c2 = 1.78X10-27 kg. Or use Atomic Mass Unit defined by mass of 12C= 12 u • Momentum: MeV/c (or GeV/c) 1 eV/c = e/c kg m s-1 • Cross sections: 1 barn =10-28 m2 • Length: fermi (fm) 1 fm = 10-15 m. By Tony Weidberg Properties of nucleons http://www.phys.unsw.edu.au/PHYS3050 Chart of the Nuclides Proton number Z=N * Unstable nuclei on either side of stable ones * Small Z tendency for Z=N * Large Z characterized by N>Z Neutron number Behaviour of nucleus is determined by the combinations of protons and neutrons Behaviour of nucleus is determined by strong and electromagnetic interactions At first sight we would expect the more neutrons the more strongly bound the nucleus – but in fact there is a tendency for Z = N Further from Z=N, the more unstable the nuclide becomes The number of unstable nuclei is around 2000 but is always increasing. * Tendency for even Z – even N to be the most stable nuclei * Even – Odd, and Odd – Even configurations are equally likely * Almost no Odd Z – Odd N are stable, and these are interesting small nuclei such as 2 H , 6 Li , 10 B , 14C 1 1 3 3 5 5 7 7 Rutherford classified radioactivity Awarded Nobel prize in chemistry 1908 “for investigations into the disintegration of the elements and the chemistry of radioactive substances” Together with Geiger and Marsden scattered alpha particles from atomic nuclei and produced the theory of “Rutherford Scattering”. Postulated the existence of the neutron Ernest Rutherford (1871-1937) The Geiger – Marsden experiment The Geiger – Marsden Experiment glass 214Po Au microscope ZnS Lead lining Their data The Rutherford Cross – Section Formula ∆p p p p 2 p. sin / 2 vo m s Secret of deriving the formula quickly is to express the momentum transfer in two ways. The first way you can see in the top parallelogram diagram. p 2m 0 sin 2 (1) The Rutherford Cross – Section Formula φ The second way is by integrating the force on the alpha across the trajectory: since we know by Newton’s law and Coulomb’s law: dp Zze 2 F rˆ 2 dt (4 0 )r p t2 t1 Zze 2 Zze 2 t2 dt cos.dt cos. 2 2 t (4 0 )r (4 0 ) 1 r p t2 t1 Zze 2 Zze 2 t2 dt cos.dt cos. 2 2 (4 0 )r (4 0 ) t1 r Eqn 3.5 At first sight this integral looks impossible because both and r are both functions of t. However the conservation of angular momentum helps: d m 0b mr dt Eqn 3.1 2 From which one sees that: dt 1 .d 2 r 0b So that (3.5) becomes 2 2 Zze 2 p cos .d (4 0 ) 0b 2 2 Zze2 2 cos (40 )0b 2 Now we can equate this with the first method of finding Δp Zze 2 p 2m0 . sin 2 . cos 2 (4 0 )b 2 This allows us to get the impact parameter b as a function of θ Zze 2 1 Zze 2 1 b cot cot s cot 0 (4 0 )m02 2 2 (4 0 ) 12 m02 2 2 2 Where S0 is the distance of closest approach for head on collision 1 m 02 2 Coulomb potential Zze 2 V (r ) (4 0 )r so * All particles scattered by more than some value of must have impact parameters less than b. So that cross-section for scattering into any angle greater than must be: 1 Eqn(3.9) b 2 s02 cot 2 4 2 b Particles fly off into solid angle given by: d 2 sin d The differential scattering cross-section is defined as: d d d d 1 1 2 2 s cot 0 d d d d 4 2 2 sin 1 1 1 1 s02 .2 cot . . . 4 2 sin 2 2 4 sin cos 2 2 2 1 2 1 2 1 s0 csc 4 s0 16 2 16 sin 4 2 Distance of closest approach d 0 o o 2 2 b Zze 2 2 1 1 vo 2 m vo 2 m (4 0 )d d The distance of closest approach “d” will be determined by: 2 2 b Zze 2 2 1 1 m v m v o o 2 2 (4 0 )d d Using: Zze 2 s0 (4 0 ) 2 . 12 m v02 1 & b s0 cot 2 2 2 2 2 b 2 s0 1 1 1 mv mv mv 0 0 2 0 2 2 d d 2 b s0 1 d d 2 2 2 d d b d d 1 .cot 2 0 2 s0 s0 s0 s0 s0 4 Solution of this quadratic gives: d 1 1 cosec s0 2 2 we get - Failure of the Rutherford Formula Increasing energy and constant angle Increasing angle and constant energy Failure of the formula occurs because the distance of closest approach is less than the diameter of the nucleus. This can happen if (a) the angle of scatter is large or (b) the energy of the particle is large enough. With Alpha particles from radioactive sources this is difficult. But with those from accelerators it becomes possible to touch the nucleus and find out its size because the distance of closest approach is given by: 1 d s0 1 cosec 2 2