NEDERL ANDS

MILITAIR

GENEESKUNDIG

TIJDSCHRIFT

VERSCHIJNT TWEEMAANDELIJKS

67e JAARGANG

JANUARI 2014 - NR. 1

M I N I S T E R I E V A N D E F E N S I E - D E F E N S I E G E Z O N D H E I D S Z O R G O R G A N I S AT I E

INHOUD

NEDERLANDS MILITAIR

GENEESKUNDIG TIJDSCHRIFT

Uitgegeven door het Ministerie van Defensie

onder verantwoordelijkheid van de

Commandant

Defensie Gezondheidszorg Organisatie

HOOFDREDACTEUR

R.P. van der Meulen

kolonel-vliegerarts

EINDREDACTEUR

A.H.M. de Bok

luitenant ter zee van administratie der

tweede klasse oudste categorie b.d.

LEDEN VAN DE REDACTIE

Dr. R.A. van Hulst

kapitein ter zee-arts b.d.

S.P. Janssen

kolonel-arts

H.W.P. Meussen

luitenant-kolonel-arts b.d.

E.G.J. Onnouw

luitenant-kolonel-vliegerarts

Dr. J. van der Plas

Bioloog

R.A.G. Sanches

kapitein-luitenant ter zee-arts

F.J.G. van Silfhout

luitenant-kolonel-tandarts

N.R. van der Struijs

kapitein-luitenant ter zee-arts

M.L. Vervelde

kolonel-apotheker

ADMINISTRATIE

majoor b.d. A. Sondeijker

secretaris NMGT

Postbus 20703, 2500 ES 's-Gravenhage

Telefoon 0165-300145

E-mailadres:

nmgt@mindef.nl

VOORBEHOUD

Plaatsing van een artikel in dit tijdschrift houdt niet in,

dat de inzichten van de schrijver worden gedeeld door

de Commandant Defensie Gezondheidszorg Organisatie

en de redactie.

Niets uit deze uitgave mag worden verveelvoudigd

zonder schriftelijke toestemming van de redactie

van dit tijdschrift.

NETHERLANDS MILITARY

MEDICAL REVIEW

Edited under the responsibility of the

Commander Defence Health Care Organisation

Postbox 20703, 2500 ES The Hague

(The Netherlands)

67E JAARGANG - JANUARI 2014 - AFLEVERING 1

Van de redactie: .................................................................................................................................

Mededelingen:

Nieuwsbrief DGO, november 2013 ...................................................................................................... 42

Nieuwsbrief DGO, december 2013 ...................................................................................................... 43

Oorspronkelijke artikelen:

De militaire dierenarts. Zijn positie en functie in de Koninklijke Landmacht

door reserve majoor-dierenarts dr. J.J. Wijnker en J. Gooijer BSc ...........................................

Het begint allemaal met hygiëne. Interview met prof. dr. Frans van Knapen

door H. Wijnker .............................................................................................................................

Beoordeling van de keukenhygiëne en voedselveiligheidsstandaarden in Kamp Heumensoord

door drs. A. Lotterman, adjudant-onderofficier E. de Haan en

reserve majoor-dierenarts dr. J.J. Wijnker .................................................................................

Risicobeoordeling op een door water overgebrachte norovirusbesmetting

voor militairen in Nederland

door reserve majoor-dierenarts dr. J.J. Wijnker en H. de Man MSc ........................................

Militair gebruik van lastdieren. De dierenarts als docent militair gebruik pakpaarden

door reserve kolonel-dierenarts B.A. Steltenpool en reserve majoor-dierenarts J. Koster .............

De Militair Veterinaire Dienst. Verleden en toekomst: vanuit een Canadees perspectief

door majoor A.G. Morrison BSc, MVB, MDS, CD ......................................................................

Voorkomen is beter dan genezen: praktische maatregelen voor de preventie van

tekenencefalitis bij militairen en werkhonden

door reserve majoor-dierenarts dr. J.J. Wijnker en dr. L.J.A. Lipman ......................................

“Levende mascottes”; voors en tegens. Een nuancering

door reserve tweede luitenant-dierenarts B. van Schaik ................................................................

War Horse. Een persoonlijke geschiedenis

door ir. J.C. Carp ...........................................................................................................................

4

12

14

16

19

20

32

35

38

Ingezonden mededelingen:

Bij- en nascholing van de Netherlands School of Public and Occupational Health .................... 3, 13, 34

25 korte verhalen ................................................................................................................................. 18

CONTENTS

VOLUME 67 - JANUARY 2014 - ISSUE 1

From the editor: ..................................................................................................................................

3

Announcements:

Newsletter Surgeon General, November 2013 .................................................................................... 42

Newsletter Surgeon General, December 2013 .................................................................................... 43

Original contributions:

The Military Veterinarian. Its position and function in the Royal Netherlands Army

by veterinarian major (res.) J.J. Wijnker PhD and J. Gooijer BSc .................................................

It all starts with hygiene. Interview with Prof. Frans van Knapen

by H. Wijnker .................................................................................................................................

Assessment of the kitchen hygiene and food safety standards at Kamp Heumensoord

by A. Lotterman DVM, warrant officer E. de Haan and

veterinarian major (res.) J.J. Wijnker PhD ......................................................................................

Assessing the waterborne risk of a norovirus infection for military personnel in the Netherlands

by veterinarian major (res.) J.J. Wijnker PhD and H. de Man MSc ...............................................

Military use of pack animals. The veterinary surgeon as pack animal instructor

by veterinarian colonel (res.) B.A. Steltenpool and veterinarian major (res.) J. Koster ...................

Military Veterinary Services. Looking back, looking forward: from one Canadian’s perspective

by major A.G. Morrison BSc, MVB, MDS, CD ............................................................................

Prevention is better than a cure: practical control measures to prevent tick-borne encephalitis

in military personnel and working dogs

by veterinarian major (res.) J.J. Wijnker PhD and L.J.A. Lipman PhD ...........................................

Live mascots; pros and cons

by veterinarian lieutenant (res.) B. van Schaik ...............................................................................

War Horse. A personal history

by J.C. Carp MSc ..........................................................................................................................

4

12

14

16

19

20

32

35

38

Paragraph advertisement:

The Netherlands School of Public and Occupational Health ...................................................... 3, 13, 34

25 short stories .................................................................................................................................... 18

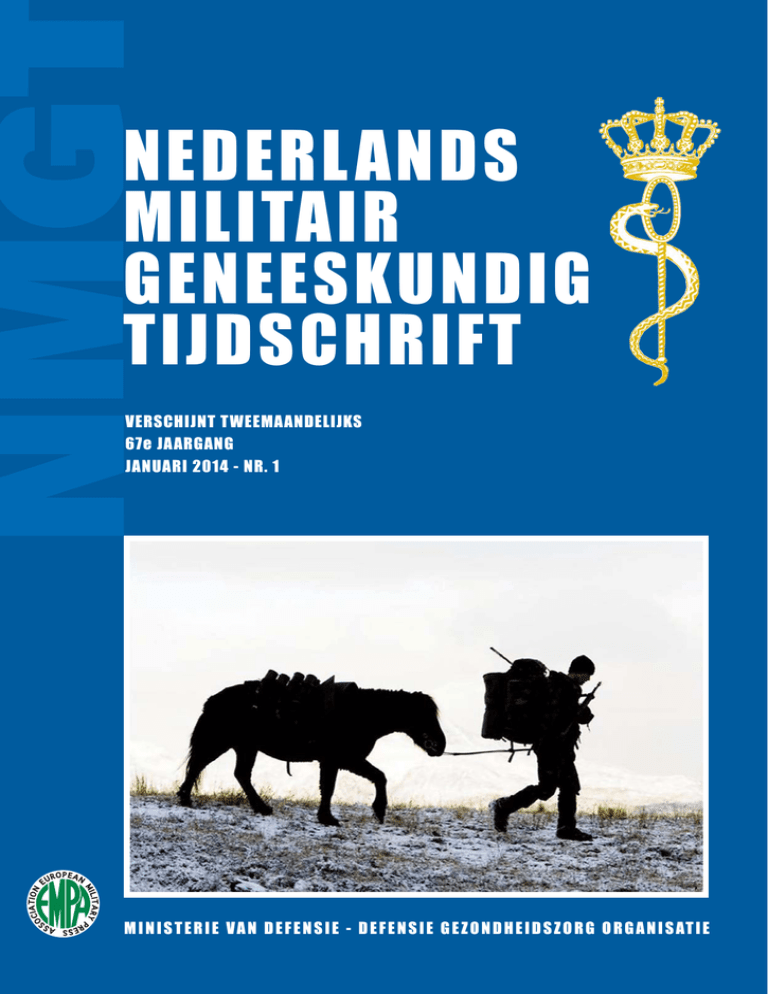

VOORPAGINA

Een marinier met een bepakte pony tijdens een bergtraining in Noorwegen.

Momenteel vindt op zeer bescheiden schaal een hernieuwde inzet plaats van paarden

voor de krijgsmacht. In het voorjaar van 2013 is daarom de eerste cursus van start

gegaan waarin mariniers worden getraind op een verantwoorde manier om te gaan

met paarden bij de inzet als lastdier. De training met draagdieren is nu nog een

pilot cursus, maar het is de bedoeling dat deze kennis weer een structureel onderdeel

wordt van het opleidingsprogramma. De militaire dierenarts draagt met deze cursus bij

aan een extra operationele inzetmogelijkheid voor de commandant, beheert de

noodzakelijke kennis en zorgt ervoor dat het op een verantwoorde, diervriendelijke

manier gebeurt.

All rights reserved

ISSN 0369-4844

3

Foto: Ministerie van Defensie.

NMGT 67 - 1-44

2

JANUARI 2014

VAN DE REDACTIE

Beste lezers,

In de laatste aflevering van het NMGT in 2013 heb ik er al

melding van gemaakt dat het eerste nummer van 2014

geheel zou zijn gewijd aan de veterinaire dienstverlening

binnen de krijgsmacht. Deze aflevering ligt thans voor u met

een scala aan interessante onderwerpen die de krijgsmacht

raken. Ook een stuk historie, waarover maar weinig bekend

is, van John C. Carp geeft een duidelijke inkijk in het

onmetelijk dierenleed gedurende WO I. Juist dit jaar is het

honderd jaar geleden dat deze oorlog uitbrak.

In zijn voorwoord geeft kolonel-dierenarts (R)

B.A. Steltenpool u een globaal beeld van de organisatie

van het veterinaire veld en de ontplooide activiteiten in het

recente verleden.

Ik wens u veel leesplezier en het allerbeste voor 2014,

De Hoofdredacteur NMGT

Kolonel-vliegerarts R.P. van der Meulen

Beste lezers,

Na het veterinaire themanummer van mei 2011 ligt er, op

verzoek, wederom een veterinaire editie, thans digitaal, van

het Nederlands Militair Geneeskundig Tijdschrift voor u.

Sinds 2011 is er het nodige veranderd. Zo is binnen het

Commando Landstrijdkrachten (CLAS) de militaire

dierenarts weer echt vertegenwoordigd. En voor uw

informatie: In de meeste landen om ons heen (o.a. België,

Noorwegen, Denemarken, Zweden) neemt het aantal

militaire veterinairen toe. Dat heeft alles te maken met de

veranderde taakstelling en nieuwe inzichten. Daarvan vindt u

in dit nummer diverse voorbeelden.

One World, One Health, One Medicine. Een gedachte die,

in het belang van mens en dier, gedurende zijn hele

imposante carrière is uitgedragen door dierenarts

prof. dr. Frans van Knapen van het Institute for Risk

Assessment Sciences (IRAS). In dit nummer een interview

met deze prominente deskundige.

In de Nederlandse krijgsmacht zijn we nu zover dat we bij

iedere brigade twee reservisten-dierenarts in de bewapening

krijgen, en bij het Operationeel Ondersteuningscommando

Land (OOCL) drie. Deze reservisten-dierenarts vallen onder

het 1 Civiel en Militair Interactiecommando (1 CMI Co) en

worden functioneel aangestuurd door de staf-dierenarts

CLAS, maar zijn ook voor andere defensieonderdelen

beschikbaar. De eerste zes dierenartsen zijn binnen en

deels al op functie geplaatst. Verder zijn er een aantal in het

proces van keuring, Algemeen Militaire Opleiding (AMO) en

de Initiële Reserve Officiersopleiding (IRO) aan de

Koninklijke Militaire Academie.

Het afgelopen jaar zijn deze dierenartsen al op diverse

fronten actief geweest. Samen met Hygiëne en Preventieve

Gezondheidszorg (HPG) zijn er veterinaire inspecties

uitgevoerd van het materieel van het Commando

Luchtstrijdkrachten (CLSK) voor oefeningen in Noorwegen

en van het CLAS-materieel dat terugkwam uit Afghanistan.

Er is met het Coördinatiecentrum Expertise

Arbeidsomstandigheden en Gezondheid (CEAG)

meegewerkt aan het uitwerken van risico inventarisaties

voor buitenlandse inzet, er is een pakpaardencursus

ontwikkeld en gegeven voor het Korps Mariniers, we hebben

ons gepresenteerd op het Conféderation Interalliée des

Officiers Médiceaux de Réserve (CIOMR) congres en

andere symposia, paraat gestaan tijdens Prinsjesdag en met

de lokale dierenarts van de CLSK-hondensecties wordt

samengewerkt om de gezondheid van deze waardevolle

viervoeters onder operationele omstandigheden te

optimaliseren. Daarnaast heeft de brigadecommandant met

deze reservisten binnen zijn staf nu de beschikking over

veterinaire kennis op het gebied van Civil-Military

Cooperation (CIMIC) in het kader van 3 D-activiteiten

(Defence, Diplomacy and Development 3 D - approach),

maar ook bij nationale operatieën wanneer bijvoorbeeld vee

uit een ondergelopen polder moet worden geëvacueerd.

Met deze reservisten haalt Defensie op een economisch

verantwoorde manier hoogwaardige, specialistische kennis

in huis. Tevens wordt zo het gehele civiele kennisnetwerk

van de reservist voor Defensie ontsloten. Dat alles met

uiteindelijk maar één doel: namelijk om “de man in het veld”

en daarmee de taken van Defensie zo goed mogelijk te

ondersteunen en uit te voeren!

Ik wens u veel leesplezier toe,

Kolonel-dierenarts (R) Bas A. Steltenpool

Stafofficier dierenarts Gezondheidszorg CLAS

MEDEDELING

Netherlands School of Public &

Occupational Health

NSPOH verhuist naar centrale locatie in Nederland

Omdat de NSPOH het belangrijk vindt dat onderwijslocaties uitstekend bereikbaar zijn vanuit alle delen van het land, met het openbaar vervoer en met de auto, gaat de

NSPOH verhuizen. Medewerkers verhuizen rond kerst naar hun nieuwe werkplek. Vanaf februari 2014 wordt het onderwijs geleidelijk op de Churchilllaan ingepland.

Deelnemers aan lopend onderwijs ontvangen persoonlijk bericht over het moment van een eventuele locatiewijziging.

De NSPOH kiest voor het zuidwestelijke deel van Utrecht vanwege de centrale ligging en

de goede bereikbaarheid. Om de dienstverlening te verbeteren, verenigt de NSPOH

kantoor én onderwijs op één locatie. Op de 10e etage in het Piet van Dommelenhuis aan

de Churchilllaan komen moderne onderwijszalen en een flexibele werkomgeving voor

medewerkers. Het pand is uitstekend bereikbaar met het openbaar vervoer en er is zeer

goede parkeergelegenheid.

Waarom deze markante toren? Als landelijk scholingsinstituut in de wereld van arbeid,

maatschappij en gezondheid hecht de NSPOH eraan in de nabijheid van

netwerkpartners te kunnen werken. Het Piet van Dommelenhuis huisvest een groot

aantal landelijke organisaties die actief zijn in “dezelfde wereld”. Elders in Utrecht huizen

talloze relevante arbo- en zorggerelateerde organisaties. De vruchtbare samenwerking

die de afgelopen jaren met het AMC is opgebouwd, zal de NSPOH vanuit de nieuwe

NMGT 67 - 1-44

locatie voortzetten. De NSPOH is hét opleidingsinstituut op het snijvlak van

maatschappij, arbeid en gezondheid. Onderwijsprogramma's slaan een brug tussen

beleid, onderzoek en praktijk. De NSPOH werkt samen met AMC - UvA. Andere

samenwerkingspartners zijn o.a. Erasmus MC, VU MC, UMCG, TNO, RIVM, GGD

Nederland, ActiZ, UWV, Hogeschool Utrecht en arbodiensten.

NSPOH vanaf 1 januari 2014 gevestigd op:

Postadres:

Postbus 20022, 3502 LA Utrecht

Bezoekadres:

Churchilllaan 11 (10e etage), 3527 GV Utrecht

Telefoon:

(030) 8100500

E-mail:

info@nspoh.nl

Internet:

www.nspoh.nl

3

JANUARI 2014

OORSPRONKELIJK ARTIKEL

The Military Veterinarian

Its position and function in the Royal Netherlands Army

Summary

As the military veterinary capacity has been very limited in the Royal

Netherlands Army (RNLA) for the past 40 years, an academic study was

done from a civilian viewpoint on the different areas of expertise to which a

military veterinarian could contribute. Starting point was the position of the

military veterinarian in the Swiss and French armed forces as an alternative

to the English or US model. This study has resulted in various suggestions

on how to apply veterinary expertise within the RNLA, which are also further

discussed in the light of the current situation.

“The evolution of the concept of

engaging troops is characterized by the

necessity for deploying forces to be

able to intervene abroad in different

state of affairs, such as preservation of

vital national interest, fighting against

terrorism, authorized law enforcement

and assistance in humanitarian

emergencies.

(…)

From reality and facts, the Armed

Forces should understand that it is in

their own interest to have professional

military veterinarians, well trained and

able to be sent abroad to support

forces during operations1.”

Introduction

“Coming out of the barracks, and

showing the people what the army

does for society” is one of the aims of

the Open Army Day 2014. Research

showed that the exact work of the

Armed Forces is unknown to most of

the Dutch population. It was therefore

surprising (and most welcomed) that

already in 2011 a young academic

from a well-known University showed

interest in the work of the army and

more specifically in that of the military

veterinarian.

As part of the Bachelor’s programme in

Veterinary Medicine at Utrecht

University, each student is required to

write a thesis, as a desk-top literature

study.

Ms Judith Gooijer, who had no military

background whatsoever, chose the

subject “The multi-facetted role of the

modern Army veterinarian” and

transformed it into her thesis entitled

“The Military Veterinarian; its future

position within Dutch Armed Forces”.

This is the more surprising given

the fact that at that time the

Royal Netherlands Army (RNLA)

seemed to have little or no veterinary

capacity. Despite the fact that there is

a great abundance of relevant material

from the English speaking countries,

Ms Gooijer chose to analyse the

position of the military veterinarian from

its position in the Swiss and in the

French army. Starting her thesis with

a historical background of the military

veterinarian, she analysed the French

and Swiss Army veterinary capabilities,

describing their current tasks. Based

on these findings a function profile was

developed, with relevance to the

Dutch Military Veterinarian.

This paper is based on the thesis

finalised by Ms Gooijer in early 2012.

The text has been revised to prevent

overlap with other papers in this

journal’s edition and more recent

information has been added. The

original thesis is available on request.

A short history on military veterinary

service

“The veterinarians have proved,

charging with sabre in hand each time

the occasion presented itself, that they

are horsemen and fighters. We

demand that they treat men or animals

indiscriminately, to carry orders under

fire, to assure the provisioning of the

assault troops, to command the porters

or the evacuation convoy after the

injured, to be an officer of topography

or a professor of agriculture. It is not

my place to judge their work but I must

point out that not even the

unfavourable conditions in which their

practitioners found themselves could

prevent these men from penetrating

and shining light on the mysterious

ensemble of tropical diseases which

they did with the power of their patient

labour and intelligent research 2.”

Over the centuries horses as well as

other animals have been used for a

great variety of tasks. As charger for

knights in armour or light hussars

relaying messages. As pack animal for

ammunition, food and forage. For

transporting artillery, soldiers,

engineering material and a thousand

other reasons. In these earlier days the

medical care for the horses was mostly

in the hands of farriers, saddlers and

skinners.

As medical science developed a more

scientific basis during the early 1700s

NMGT 67 - 1-44

4

JANUARI 2014

by Major (R) Joris J. Wijnker DVM PhDa

and Judith Gooijer BScb

and forced by several disastrous

outbreaks of cattle plague or

Rinderpest in Europe, the need for a

science-based veterinary education

was felt. This led to the opening of

the first veterinary college in Lyon,

France by Mr Claude Bourgelat in

January 17623.

When Napoleon marched his army into

Russia, it suffered great losses; many

soldiers died of famine, exposure to the

elements and on the battlefield. Many

horses died too, for the same reasons.

A Dutch cavalry officer in French

service, C.A. Geisweit van der Netten,

wrote in his journal (1815):

“The various campaigns we witnessed,

in particular the one in Russia,

provided us a lot to think about related

to the means that can be used to

maintain the health of the war horses.

That is because the poor condition of

the cavalry and the great loss of horses

can largely, if not entirely, be attributed

to a failure in keeping the horses

healthy. This took place in the French

armed forces and had a decisive

influence on the success of war (…)4.”

As a result of the disastrous Russian

campaign in 1812, Napoleon decided

there should be five veterinary schools,

of which one was to be established in

the Netherlands.

After a difficult start, in which various

riding schools were established in

different cities teaching equine care,

finally in 1821, the Imperial Veterinary

College (“Rijks Veeartsenijschool”) was

established at Utrecht.

Although one of the main reasons for

its foundation was the cattle plaque

from which the Netherlands suffered a

great deal, the Army was quick to

benefit as well.

Prior to 1821 a start was made by

hiring foreign veterinarians into its

service. For example, in 1815, the

German equine veterinarian

F.H.S. Dehne was brought to the

Netherlands.

a

Specialist RVAN Veterinary Public Health,

Institute for Risk Assessment Sciences, Division

Veterinary Public Health, University of Utrecht,

The Netherlands, supervising lecturer of

Ms Gooijer for her thesis.

Brigade veterinarian, Land Operation Support

Command, Royal Netherlands Army.

b

Institute for Risk Assessment Sciences,

Division Veterinary Public Health,

University of Utrecht, The Netherlands.

Article received October 2013.

Earlier that year, he had graduated in

Berlin. After passing his exams before

the Leiden Committee, he became the

first equine veterinarian commissioned

in the Netherlands Armed Forces.

1816 can therefore be regarded as the

year in which the Dutch Military

Veterinary Service was officially

established5.

The Military Veterinary Service

(Militair Diergeneeskundige Dienst /

MDD) was part of the Military Medical

Service and was under its command,

which meant that any Health Officer

could nullify a useful or necessary

treatment ordered by a military

veterinarian. In 1856, the MDD was

segregated from the Medical Service

and the Health Officer no longer could

influence the activities of a military

veterinarian. However, only 6 years

later this decision was revoked and

once again the MDD was under

supervision of the Military Medical

Service. Not until 1914 did the MDD

become functionally independent.

A decision that was formalised in 1923

and lasted until 1940 after which the

army was fully mechanised and the

MDD disbanded. With the retirement

in 1973 of Colonel-Veterinarian

A.J. Braak the last original equine

veterinarian left the army. One of his

last assignments was Commanding

Officer of the Military School for

Hygiene and Preventive Medicine at

Neerijnen, which was closed after his

retirement5,6,7.

France

The French Armed Forces

France has a long military history, next

to its long history of colonialism and

nationalism, requiring an important role

for the French Armed Forces in

maintaining its position as a global

power8. For decades, the French vision

of Europe was founded on

three principles: inter-governmentalism

that minimizes the infringement on

French sovereignty, French leadership,

and a European Europe that is not

influenced by the United States.

For a while, France therefore saw the

European Union as a “force multiplier”,

a means to exert and increase

influence on the world stage. Due to

the French ambitions at the political

level, there was always a great

preparedness to intervene, not only

through diplomatic means, but also in

the military field. Before France joined

NATO, it had some military

collaborations with other countries,

ranging from technical support to the

obligation of giving military assistance.

French leaders have used global

deployment and possible intervention

by the French Armed Forces as one of

their most important instruments in

their foreign policy.

However, since Operation Desert

Storm (1991), the command structure

has been changed to facilitate such

expeditionary operations. During the

last years the organisation and

execution of national operations has

also been modified extensively, mainly

due to a high level of unpredictability

on international levels, being a

continuous source of risks and possible

threats. Although after the Gulf War its

nuclear defence budget has been

reduced by 80%, France still derives

its status from its nuclear deterrence,

a cornerstone of its Defence and

Security Management. In 2008,

President Sarkozy announced that the

French Armed Forces had to become

smaller, more mobile and better

equipped in the fight against terrorism.

Identification and destruction of

terroristic networks is at present

one of the main tasks of the French

Armed Forces. In 2009, the French

Parliament agreed with a full return of

France in the NATO’s military

command structure, after it had left this

organisation in 1967. Due to these new

developments, the general goal of the

Ministry of Defence is to protect the

French territory, its population and

interests. This corresponds to other

missions in the framework of

international agreements (NATO)

and European defence. Besides

maintaining the peace and national

cohesion, French Armed Forces are

also involved in maintaining global

stability. Clear examples are the recent

deployment to Afghanistan and current

EU maritime missions off the African

coast and mission to Mali 9,10,11,12.

The French Military Veterinarian

Also in France, the image and

perception of the role of military

veterinarians are frequently connected

with veterinarians treating only horses.

This association stems from the

dominant presence of horses during

the wars until the First World War and

the necessity to have veterinarians to

care for them. In the beginning of the

XXI century, there are still military

horses present, but the role of the

military veterinarians is now completely

different. This is mainly due to

operational changes (fewer horses)

of the Armed Forces and different

deployment strategies which

include foreign intervention and

NATO / UN cooperation9.

The French Armed Forces have a

professional Military Veterinary Corps,

which participates in several overseas

NMGT 67 - 1-44

5

JANUARI 2014

operations. Military veterinarians are

able to join the Armed Forces in all

theatres of operation. Yearly,

10 - 20 veterinarians are deployed in

various missions, lasting 2 - 6 months.

In all, a fulltime equivalent of

50 months per year is provided. The

military veterinary activities are under

supervision of the Medical Service.

Veterinary support is given to the entire

French Armed Forces; each military

region is able to use veterinarians. The

Military Veterinary Corps includes

75 veterinary officers, in direct support,

in military research institutes and

studying at the military medical training

facilities. In addition, 35 veterinary

technicians, both military and civilian,

and 50 veterinarians from the

operational reserve (part-time work or

short duration missions) are available.

The French Military Medical Service

consists of 6 regional management

authorities and each of them has a

veterinary office with 2 officers. These

veterinarians are responsible for

coordinating veterinary activities in

18 veterinary sectors (each veterinary

sector is in charge of supporting forces

in its own territory) and 5 veterinary

services in specific military units, which

are specialised in providing veterinary

support to the units using military

animals. Five veterinarians are posted

overseas. They are under the

command of the French military

medical authorities of overseas

departments and territories (Figure 1).

The two main objectives in the field are

to support military personnel and

protect their health, requiring extensive

safety and quality checks of food and

water. In addition, military veterinarians

are appointed to conduct official food

inspections for units and services

under the authority of the Ministry of

Defence. The Ministry of Defence and

the Ministry of Agriculture also signed

an agreement for cooperation between

military veterinarians and civilian

veterinary inspectors. Besides food

safety, the veterinary tasks include

animal health care, curative and

preventive animal medicine.

Furthermore, they keep an eye on

animal welfare and laboratory animal

protection.

New ideas and perspectives are

developed for veterinarians due to new

objectives of the French Armed Forces,

such as combating terrorism. A recent

subject has been to provide veterinary

support for military animals, by training

dog handlers on first-aid. Additionally,

military veterinarians have been

receiving training in epidemiology and

veterinary public health to support

Ministry of Defence

Military Medical Service

Military Veterinary Corps

35 Veterinary technicians military & civilian

6 Regional management authorities /

per RAM:

50 Veterinarians Operational Reserve

1 Veterinary office /

2 officers

18 Veterinary sectors

75 Veterinary officers

Military research institutes

(6 vets)

Per sector 2 officers & 2 vet techs /

responsible for supporting forces in sector

Medical military training

school (4 vets)

5 Veterinary services in support of canine

and horse units

Supporting Forces

(65 vets)

5 Veterinary officers posted overseas

Switzerland “will exercise its neutrality

in a way that allows it to take the

Figure 1: Organogram of the French Veterinary Corps1.

tactical forces deployed in foreign

operations. In conclusion: closely

linked to the deployment of Armed

Forces, the French military

veterinarians contribute to the risk

management related to food safety,

water quality, prevention of epizootics

and zoonoses and protecting animal

health1.

Switzerland

The Swiss Armed Forces

Switzerland has a standing policy of

active neutrality, and will therefore not

be involved in conflicts abroad, nor can

it join NATO as a member. However,

NATO members and Switzerland share

some key values, such as international

humanitarian law. In line and within the

limits of its neutrality, Switzerland can

participate in peace-supporting

operations under UN or OSCE

mandate13.

Art. 54 (Bundesverfassung der

Schweizerischen Eidgenossenschaft):

“The Confederation shall ensure that

the independence of Switzerland and

its welfare is safeguarded; it shall in

particular assist in the alleviation of

need and poverty in the world and

promote respect for human rights and

democracy, the peaceful co-existence

of peoples as well as the conservation

of natural resources14.”

Art. 58: “Switzerland shall have armed

forces. In principle, the armed forces

shall be organised as a militia.

The armed forces shall serve to

prevent war and to maintain peace;

they shall defend the country and its

population. They shall support the

civilian authorities in safeguarding

the country against serious threats

to internal security and in dealing

with exceptional situations. Further

duties may be provided for by law.

The deployment of the armed forces

shall be the responsibility of the

Confederation8,15...”

Having a militia army, Switzerland

requires every able-bodied male in

the age of 19 to 26, to serve for at least

260 days. They receive 18 weeks of

mandatory training, followed by

seven 3-week intermittent recalls for

training during the next 10 years16.

Membership of the European Union

would be an option as the EU has no

military basis. Although Switzerland is

not a member, it has a special trade

agreement with the EU. Switzerland is

a country with many cultures and

religions, presenting the origin for its

opinion that if a country is not

externally neutral, it cannot be

internally cohesive.

NMGT 67 - 1-44

Since 1996 Switzerland participates in

the NATO programme: Partnership for

Peace (PfP). This partnership seeks to

intensify security policy and military

cooperation in Europe. The Swiss

participation in the PfP is compatible

with neutrality as there is no

requirement for NATO membership

and no obligation to provide military

support in the event of armed conflict17.

Recent developments like globalisation

and innovation create a whole new

geo-political situation. In 1993, the

Swiss Federal Council set out to

determine how it intends to continue its

neutrality under the changed

circumstances. According to the report,

neutrality alone cannot protect their

country against new dangers such as

terrorism, organised crime and

destruction of the environment. In

2001, the Swiss revised their Military

Act, which now regulates Swiss

participation in peace support

operations of the UN and provides the

basis for arming Swiss peace support

forces abroad for self-protection.

Operational support is compatible to

neutrality if it is based on a UN Security

Council mandate.

6

JANUARI 2014

necessary military precautions for its

own defence, also with respect to new

threats. Depending on the threat, this

could also entail international

cooperation in the preparation of

defensive measures17 .”

The Swiss Military Veterinarian

The primary task of graduated

veterinarians in the Swiss Armed

Forces is to secure the health of men

and animal. This includes curative

veterinary medicine of military animals

(horses, mules and dogs), but also

training and educating kitchen

personnel on food safety and strict civil

food legislation18.

The Swiss Armed Forces have many

animals serving in the army, first of all

the military working dogs (MWD).

These dogs are trained for surveillance

and protection, as rescue dogs and as

sniffer dogs for explosives and drugs19.

Horses and mules are also used, for

patrols and transport of material on

tracks impassable for motorized traffic.

These animals are used mainly in the

Alps and other mountainous areas4.

Horses and mules are also used in

“national operations”, such as clearing

away wood after storms and

avalanches20.

For training and working with these

animals different personnel is used,

such as dog handlers, veterinarians,

farriers and the “veterinärsoldat” or

military veterinary assistant / nurse

practitioner21.

To become an army veterinarian,

special training is required. After

graduation as veterinarian an

additional course of 16 weeks is

required16 to become

“Veterinärarztoffizier” or Veterinary

Officer. Veterinarians can complete

their compulsory army service in this

capacity18.

During the 16 week course, the

candidate army veterinarians are

trained on the following subjects:

curative medicine and deployment of

military dogs and horses, horse

shoeing, food safety, working in the

mobile animal clinic, dental surgery of

horses, feeding and day-to-day care. In

addition the candidates also receive a

military training, including shooting and

navigation, horsemanship and their

military driving license18.

In the “Kompetenzzentrum

Veterinärdienst und Armeetiere”

(Army Command Competence Centre

Veterinary and Animal Centre) there is

one fulltime veterinarian22. The other

veterinary officers have a part-time

position, as they work in private

practice. In total 600 days are served in

this capacity as part of their

compulsory army service, which

includes the 16 week course of extra

training. Each year army veterinarians

are recalled for training, and for this

purpose are assigned to different units:

Army food hygiene inspection team, a

veterinary company or a working dog

company23,24.

The inspection team is tasked with

food inspection, hygiene (measures

and compliance), training of army

kitchen personnel and development of

documents and procedures on food

hygiene & safety (Figure 2)23.

In case of national emergencies

involving animals, the army can

provide support to civilian areas,

especially in the field of the veterinary

service25.

The Netherlands

The Royal Netherlands Army (RNLA)

Article 97 of the Dutch Constitution

reads as follows:

“There shall be Armed Forces for the

defence and protection of the interests

of the Kingdom, as well as to maintain

and promote the international legal

order26.”

The RNLA can be deployed for

national security reasons, both at home

and abroad. National security is at

stake when vital interests of the

Dutch Government and/or society

are threatened or when there is

Army

Logistics training unit

Army Command Competence Centre Veterinary and

Animal Service

Admin / personnel

Training

Staff

Army kennel

Militia units

Basic training

Dog training

NCO / Veterinary Officer’s

training

Canine Unit training

Militia staff

Veterinary Service

3rd Veterinary company

9th Mounted supply train

Special courses

19th Mounted supply train

Search & rescue dogs

12th Mounted supply train

Guard dogs

13th Mounted supply train

Snidder dogs

14th Mounted supply train

Dog care

Figure 2: Organogram of the Swiss Veterinary Corps (assisted by Mr Suter of the Army Command Competence Centre Veterinary and Animal Service).

NMGT 67 - 1-44

7

JANUARI 2014

a potential social disruption.

Interests are: territorial security,

economic and ecological safety,

physical safety (including public health)

and social and political stability. The

task of the government is to ensure

and promote this national security, by

preventing disasters and crises.

However, in case of crisis, military

support can be provided to the

Dutch civil authorities as special

knowledge and capacity (e.g. mobile

field hospitals) are readily available in

response to the situation27.

Security Assistance Forces) supported

the Afghan government in maintaining

peace31. When deployed in a mission,

military personnel can also be

deployed in reconstructing a postconflict area32. To this end the

so-called “1 CMI Command” exists

(Civil Military Interaction Command),

interacting with local key players and

non-governmental organisations

(NGOs). The CMI unit has the specific

task to support a military mission or

assignment with non-kinetic expertise,

advising the Commander.

By stimulating global security, the core

reason for international crime and

migration diminishes. The main tasks

therefore of the RNLA focusses on

intelligence gathering (MIVD), security,

protection and deployment of Special

Forces. This usually results in taking

part in an international joined combined

effort for crisis management and

disaster relief, mostly under NATO or

UN command28,29,30.

1 CMI Command (1 CMI Co) is part of

the LOSC (Land Operation Support

Command / OOCL) and consists of,

apart from a small staff, fulltime military

personnel organised in CMI support

units (CSU) and reserve officers

organised in different network groups

according to the PMESII structure

(Political, Military, Economic, Social,

Infrastructure and Information). These

reserve officers consist of so-called

functional specialists: People with a

civil position requiring specific

expertise and skills31.

In the past, several veterinary

specialists have been deployed in

At this moment, the Armed Forces are

deployed in several missions, for

example in Mali. Recently in

Afghanistan, The ISAF (International

crisis management and national

disasters. They have also served in

Iraq and Afghanistan, for example

tending to local livestock32,33.

The military veterinarian:

organisation, expertise and skills

The position of a veterinarian in military

service has developed from an equine

practitioner to a multi-disciplined

professional, covering preventive and

curative veterinary medicine,

epidemiology, food safety, hygiene and

(veterinary) public health. Many

countries have responded to this

broadened scope by giving the military

veterinarian a clear basis within the

Armed Forces. Although the RNLA still

do not have a full-time position for a

military veterinarian, a substantial

veterinary capacity is under

construction by using reserve officers.

These officers are recruited and trained

by 1 CMI Co, but functionally

embedded with the combat brigades

and the LOSC (Figure 3). They work

closely with the preventive medicine

(PM) specialists, the medical

specialists, the staff veterinarian and

with the experts from CEAG (Expertise

Centre for Force Health Protection).

Parliament

Ministry of Defence

State Secretary

Defence Material

Organisation

Support Command

Commander of the Armed Forces

Army Command

11 Air Mobile Brigade

MV

PM

Navy Command

13 Mechanised Brigade

MV

Air Force Command

Land Operation Support

Command

43 Mechanised Brigade

PM

MV

PM

Military Police

MV

PM

1 CMI Co

MV

Figure 3: Organogram Dutch veterinary capacity. Based on: www.defensie.nl/landmacht/eenheden

NMGT 67 - 1-44

8

JANUARI 2014

Since 1996, PM specialists are

permanently deployed in all missions.

Their tasks are executive, but also

initiating inquiries and providing advice

to the medical staff and operational

command34. Many tasks are closely

linked to the areas of expertise of the

military veterinarian35. The way these

tasks can be further integrated will be

clarified later on in this chapter.

Though not exclusive, the following

areas of expertise have been identified

in which the military veterinarian can

be useful for the RNLA: Animal

Medicine, Emerging Diseases, Disaster

Control, Public Health and Hygiene

and Development Projects36. These

areas will be addressed in more detail

below, underlining their importance and

operational structure.

Animal Medicine

The first traditional area of expertise for

the military veterinarian is Animal

Medicine. Military animals, including

horses and dogs are used for a variety

of tasks. For example Military Working

Dogs (MWDs) are a valuable asset in

today’s missions37. They are used in

detecting roadside bombs (EIDs),

hidden caches of weapons or

ammunition, outdoors, indoors or in

vehicles, protecting the compound and

equipment and to explore landing

strips. In addition MWDs are used as

so-called “Less Lethal Weapons”, in

crowd control. These MWDs go out

with their handler on patrol, where they

serve as early warning system against

ambushes or for identification of armed

terrorist groups. Because of their

unique and versatile skills and their

expensive and difficult training, these

MWDs are regarded as high-value

assets to the Armed Forces37,38,39.

Prior to deployment, a disease risk

assessment should be made regarding

the theatre of operation in which the

animal will be serving40. Prior to and

during the mission the animals will be

checked for any diseases and other

disorders, the appropriate vaccination

scheme and parasite control will be

applied and the animals will receive

any required treatment for injuries

sustained during operations 38,40.

Besides direct assistance,

veterinarians can make this

assessment, they can instruct the

handlers on general care and

treatment and give specific

geographical information relevant for

the acclimatisation of the animals to

(extreme) warm or cold conditions1,40.

When the MWDs go on patrol with their

handler, there is no Dutch military

veterinarian present who can provide

medical care. In case of injuries, for

example after an attack, it is the

responsibility of the handler to be able

to administer first-aid. Veterinarians will

need to be in a position to train the

handlers for this important task.

During military deployment, there will

not only be the animals of the Armed

Forces for which the veterinarian may

be called upon. Animal Medicine can

also apply to local farm animals or local

wildlife surrounding the compound38.

Pest control (the extermination or

removal of any unwanted animal from

the compound) is done by the PM

specialists. A veterinarian can assist

them on policies and procedures, while

the executive tasks lie with the PM

specialists. This is mostly done using

baited traps (e.g. rodents) or specific

actions to localise, catch and remove

the targeted animal from the

compound. PM specialists may apply

deadly force to neutralise a specific

threat (e.g. rabid dog)35.

It is not uncommon that military

personnel adopt local stray dogs or

other animals and bring these into the

compound. These animals are

promoted to mascot status and treated

like pets. Seemingly quite harmless,

these animals, wildlife and

domesticated pets, can be a real

nuisance and more importantly, they

can be a potential carrier of animal

diseases, zoonotic pathogens, creating

a potential health risk to all military

personnel (men and animal!)1. Although

it is a standing order that all pets in any

shape or form are strictly forbidden

within the compound, exceptions to

this rule can be made by the

Commander, consulting a PM

specialist or military veterinarian. For

example cats can be used to suppress

a possible rodent infestation of the

compound or dogs can be used as

controlled animals to occupy the

natural territory within / surrounding the

compound, keeping out unwanted stray

animals. In all such cases each

requirement concerning the animal’s

health and welfare must be met.

Emerging Diseases

About 75% of the human emerging

diseases in appear to be zoonotic 41.

A wide variety of animal species, both

domestic and wild, can act as reservoir

or vector for these pathogens, which

may be viruses, bacteria or parasites38.

These pathogens can be a threat for

military personnel deployed, for the

health of the local people and local

farm animals. People can become

infected through contacts with live

animals, products of animal origin (e.g.

NMGT 67 - 1-44

9

JANUARI 2014

meat, milk), excreta or mediated by

airborne vectors such as flies and

mosquitoes42. Pathogens can also

enter the Netherlands using different

pathways, which also include all

returning military equipment and

vehicles used during the operations,

with pathogens embedded in mud,

manure or any form of dirt attached to

its surfaces34,43.

During their deployment, military

personnel come into contact with

different cultures and are exposed to

other environments, climatic conditions

and (un)known diseases, including

zoonoses. Rabies is a clear example of

an animal and zoonotic disease which

can be contracted via saliva (bites)

from e.g. bats, foxes, dogs and cats 44.

Officially the Netherlands is free of

rabies since 1923 (though some

incidents caused by illegal import of

dogs make this status questionable),

but in parts of Africa, in Eastern

Europe, India and Asia rabies is

endemic45. Veterinarians can train and

inform military personnel about these

diseases and underline the health risks

of certain ill-informed actions like

adopting local stray dogs as pets or

consuming locally produced foods of

unclear origin1,37.

Military veterinarians can therefore act

as gatekeepers, in the context of food

safety (discussed later) and the

exposure to diseases. Prevention,

detection and control of diseases are

clear parts of the main tasks of a

military veterinarian, also in the context

of repatriation. The transmission of

(zoonotic) pathogens from the theatre

of operation to the homeland (e.g.

foot-and-mouth disease or avian

influenza), is a real threat which must

be minimized due to its massive impact

on animal and public health, economic

damage and possible negative public

opinion for the mission itself1,42.

Leading example is rabies: When the

English soldiers returned home after

World War I, there was a clear

increase of animals infected in England

with rabies. Although a direct link could

not be established, a realistic scenario

shows how rabies was carried over by

the returning soldiers1.

Various NATO Standardization

Agreements (STANAGS)42 are already

in place or are in the process of being

finalised, covering these issues. In

addition, in the operational planning

phase of missions and exercises these

risks are now being considered,

supported by assessments drafted by

CEAG to which the military veterinarian

and other specialists can contribute.

Interestingly, these assessments can

also apply when material and

personnel are shipped to a third

country which has specific

requirements on reception from the

Netherlands. The system therefore

works two ways.

Disaster control

The RNLA can provide aid and

assistance in the case of (natural)

disasters or national emergencies,

e.g. large-scale outbreaks of animal

diseases, forest fires or floods. Recent

emergencies where assistance was

provided are the foot-and-mouth

disease outbreak in 2001, the

EL AL plane crash in the Bijlmer

(Amsterdam) in 1992, the great floods

in Zeeland province in 1953 and even

in 2012 in Friesland and Groningen

province when the water levels

exceeded the critical limits.

The 2010 brochure published by the

Dutch Ministry of Defence on National

Operations clearly describes how the

Armed Forces can provide support to

civil emergency response units in case

of large-scale emergencies. It also

describes how separate entities can

merge into fast acting response teams

with regular military personnel

supported by reservists and other

functional specialists46,47.

In addition to the National Operations,

Dutch military personnel can be

deployed to disaster areas in other

parts of the world or provide

humanitarian support in areas under

UN supervision. In these cases, the

deployment of military veterinarians is

of vital importance in matters

concerning water and food safety and

zoonotic disease risks.

Large-scale natural disasters

(tsunami’s, forest fires or droughts)

may also result in massive loss of

animal life (livestock and wild life),

which can turn into a serious health

risk for both men and animals surviving

in the same area due to the presence

of decomposing carcasses polluting

the environment. Pre-existing

emergency protocols and on-the-spot

assessments can be drafted by military

veterinarians, working closely together

with local authorities and other NGOs

deployed, to reduce or avert further

health risks and loss of life48,49.

Public Health and Hygiene

Over the years the objective of the

RNLA has developed into primarily

peace-keeping, stabilising and

rebuilding missions abroad. This

adapted scope has also changed the

circumstances and potential risks that

should be taken into account. At first

glance public health does not appear to

be in the veterinarian’s field of

operations, but as both water and food

safety & quality fall under public health

it becomes apparent that the military

veterinarian has an important

responsibility towards operational

readiness and personal health. Already

not a simple task in the Netherlands by

maintaining high levels of

microbiological safety and even more

challenging when facing the sometimes

harsh operational conditions under

which good hygiene and food safety

need to be managed.

As climatological conditions in mission

areas abroad can differ dramatically to

the domestic situation, a local

infrastructure is often non-existent

(destroyed, never developed) with little

sanitary resources and sewerage in

working condition. Local businesses

and markets are often low in hygienic

conditions and in all, there are many

microbial risks that face the military

personnel deployed in these

areas34,49,50.

In addition, when military personnel is

deployed to such inhospitable areas for

strategic or relief missions, fatigue and

operational stress may make them

more susceptible to increased

pathogen levels than intensive training

can prepare them for. Subsequently,

an increase in non-battle injuries may

result in reduced fighting strength and

operational capabilities.

Therefore it is of vital importance that

all factors involved are well known and

fully covered to ensure the success of

the mission at hand, requiring a high

degree of professionalism35.

Several areas in which PM specialists

and military veterinarians can

cooperate closely range from

assessing bioterrorism risks (CBRN

threats) to water and food safety

management in mission areas1,49,51.

Again, the PM specialists have a more

executive role in acquiring

local data, by doing for example

microbiological checks on water

and food supply or collecting insects

for further entomological

determination52,53. The role of the

military veterinarian will be to assist on

the interpretation of the data and

development or amendment of

protocols aimed to reduce the

exposure risks of military personnel.

For these tasks liaising with local

competent authorities, veterinarians or

available laboratory facilities is of vital

importance to ensure the required

assessment and management of

identified (potential) risks in the mission

areas.

NMGT 67 - 1-44

10

JANUARI 2014

Development Projects

The fifth area of expertise of the

military veterinarian is herd

management, animal health care and

husbandry (e.g. breeding, feeding,

housing) in host nation countries.

Healthy animals deliver safe food,

a better quality of life for the local

families and also impact on the

economies of those countries, as these

healthy animals can also be applied as

means of transport or in agriculture37,54.

As described earlier, the RNLA include

the 1 CMI Co, consisting of military

staff and functional specialists, which

can be deployed as part of a Provincial

Reconstruction Team (PRT). Within the

PRT, military personnel, civil personnel

(from e.g. the Ministry of Foreign

Affairs) and NGOs work together to

establish projects in the mission area

aiming to improve the quality of life of

the local population and acquiring a

level of self-sufficiency after the

PRT mission is terminated50,55,56,57,58.

A very important task dedicated to the

hearts and minds of the people who

have suffered long and hard.

In conclusion

It is quite clear that the role of the

military veterinarian has evolved

dramatically from a dedicated equine

practitioner to a “Jack-of-all-trades”,

being a well-trained professional with

a practical mind-set focussed to tackle

and overcome any problem he or she

will encounter.

The position of the military veterinarian

is well established in most NATO

partners and other countries, whereas

the military veterinary capacity has

been minimal in the Netherlands

Armed Forces for several decades.

However, the organisational role of the

PM units with their specific tasks and

embedded in the operational units,

provides an excellent framework to

re-incorporate the military veterinarian

and his knowledge in The Netherlands

Armed Forces. Using the Swiss and

French Veterinary Services as possible

examples, the Dutch military

veterinarians are now becoming

organised in such a way to maximise

efficiency and synergy. The close

cooperation of these reserve officers

with other military and civil

professionals (e.g. PM, CEAG and the

Institute for Risk Assessment

Sciences) is a key element in their

current role. With their presence and

using these respective networks,

a broad scope of knowledge comes

easily available for the soldier in the

field. Although much remains to be

done, a clear start has been made to

create an optimal veterinary mix and

cost effectiveness for today’s Armed

Forces.

After much effort by Colonel (R)

Veterinarian Bas Steltenpool and

Professor Frans van Knapen

(IRAS Division Veterinary Public

Health, University of Utrecht) the

military veterinarian is now on its way

back to full operational status. Linked

to the PM units, 1 CMI Co and CEAG,

they are ready to go wherever the job

takes them.

S A M E N V AT T I N G

DE MILITAIRE DIERENARTS

Zijn positie en functie in de

Koninklijke Landmacht

Gezien het feit dat de rol van de

militaire dierenarts vrij beperkt was in

het Nederlandse leger gedurende de

afgelopen 40 jaar, is er gekeken naar

een mogelijke invulling van taken en

structuur. Vanuit een historisch

perspectief, met de Franse en

Zwitserse militaire veterinaire korpsen

als Europese voorbeelden en de wijze

waarop het Nederlandse leger thans

opereert, wordt een overzicht gegeven

van de aandachtsvelden waaraan de

veterinaire (reserve-)officier kan

bijdragen. Op het organisatorische vlak

is er over de afgelopen twee jaar veel

vordering gemaakt om de militaire

dierenarts weer in actieve dienst te

hebben.

References:

1.

Kervella J.Y., Marié J.L., Cabre O., Dumas E.:

(2011). Veterinary support in the Armed Forces.

Nederl Mil Geneesk T, 64, 96-100.

2. Davis D.K.: (2006). Prescribing Progress: French

Veterinary Medicine in the Service of Empire.

Veterinary Heritage, 29 (1), 1-7.

3. Egter van Wissekerke J.: (2010). Veterinair

onderwijs en militaire paardenartsen. Van kwade

droes tot erger (p. 183-236). Rotterdam:

Erasmus Publishing.

4. Egter van Wissekerke J.: (2010). De rol van het

militaire paard in oorlogsvoering.

Van kwade droes tot erger (p. 31-64).

Rotterdam: Erasmus Publishing.

5. Egter van Wissekerke J.: (2010). Veterinair

onderwijs en militaire paardenartsen.

Van kwade droes tot erger (p. 183-236).

Rotterdam: Erasmus Publishing.

6. Steltenpool B.A.: (2004). Dienaren van

Aesculaap en Mars. Mars et Historia, nr. 3,

47- 56.

7. Mossel D.A.A., Koolmees P.A.: (2003).

Veterinairen in militaire dienst. ARGOS,

nr. 29, 425-433.

8. Bundesverfassung der Schweizerischen

Eidgenossenschaft (1999, stand am

1 Januar 2011). Artikel 58. Geraadpleegd via:

http://www.admin.ch/ch/e/rs/101/a58.html

(Engels) en http://www.admin.ch/ch/d/sr/

1/101.de.pdf (Duits).

9. Homan K.: (2006). Verval en vernieuwing:

Het Franse buitenlands en veiligheidsbeleid.

Atlantisch Perspectief, 6, 9-14.

10. Ministère de la Défense et des anciens

combattants (10-07-2010). The Missions of

National Defense. Geraadpleegd via

http://www.defense.gouv.fr/english/portaildefense/ministry/missions/the-missions-ofnational-defence

11. United States Central Command. France.

Geraadpleegd via

http://www.centcom.mil/france/

12. 2009, 11 maart. Frankrijk wordt weer volwaardig

NATO-lid. Het NRC. Geraadpleegd via

http://vorige.nrc.nl/article2177615.ece

13. North Atlantic Treaty Organization (2012,

5 Maart). NATO’s relations with Switzerland.

Geraadpleegd via: http://www.nato.int/cps/

en/natolive/topics_52129.htm

14. Bundesverfassung der Schweizerischen

Eidgenossenschaft (1999, stand am

1 Januar 2011). Artikel 54. Geraadpleegd via:

http://www.admin.ch/ch/e/rs/101/a54.html

(Engels) en http://www.admin.ch/ch/d/sr/

1/101.de.pdf (Duits).

15. Eidgenössisches Departement für Verteidigung,

Bevölkerungsschutz und Sport (VBS), Schweizer

Armee: Chef der Armee CdA (2007). Strategie

Schweizer Armee 2007. Bern: Vorsteher

Eidgenössisches Departement für Verteidigung,

Bevölkerungsschutz und Sport (VBS).

16. Central Intelligence Agency (06-03-2012). The

World Factbook: Switzerland. Geraadpleegd via:

https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/

the-world-factbook/fields/2024.html

17. Federal Department of Defense, Civil Protection

and Sports (DDPS), Federal Department of

Foreign Affairs (DFA). Swiss Neutrality. Bern:

Communication DDPS.

18. Kompetenzzentrum Veterinärdienst und

Armeetiere (27-02-2012). Armeetiere:

Veterinärarzt: Vorteile Vet Az Of. Geraadpleegd

via: http://www.he.admin.ch/internet/heer/de/

home/themen/kompetenzzentrum/werde_

armeetierspezialist/veterinaerarzt/vorteile.html

19. Kompetenzzentrum Veterinärdienst und

Armeetiere (17-08-2011). Armeetiere: Einsatz:

Diensthunde. Geraadpleegd via:

http://www.he.admin.ch/internet/heer/de/

home/themen/kompetenzzentrum/Einsatz/

milizhundefuehrer.html

20. Kompetenzzentrum Veterinärdienst und

Armeetiere (17-08-2011). Armeetiere: Einsatz:

Tragtiere. Geraadpleegd via:

http://www.he.admin.ch/internet/heer/de/

home/themen/kompetenzzentrum/Einsatz/

trainsoldat.html

21. Kompetenzzentrum Veterinärdienst und

Armeetiere (14-07-2011). Armeetiere:

Veterinärsoldat. Geraadpleegd via:

http://www.he.admin.ch/internet/heer/de/

home/themen/kompetenzzentrum/werde_

armeetierspezialist/0.htm

22. Eidgenössischen Departement für Verteitigung,

Bevölkerungsschutz und Sport VBS (2011,

12-04). Kurativer Vet D: Befehl kuratiever

Veterinärdienst Komp Zen Vet D & A Tiere.

Bern: VBS.

23. Kompetenzzentrum Veterinärdienst und

Armeetiere (17-08-2011). Armeetiere:

Lebensmittelsicherheit in der Armee - das

Lebensmittelhygiene-Inspektorat der Armee

(LIA) Geraadpleegd via: http://www.he.admin.

ch/internet/heer/de/home/themen/kompetenzzen

trum/veterinaerarzt.html

24. Kompetenzzentrum Veterinärdienst und

Armeetiere (23-02-2012). Armeetiere:

Veterinärarzt: Diensttage. Geraadpleegd via:

http://www.he.admin.ch/internet/heer/de/

home/themen/kompetenzzentrum/werde_

armeetierspezialist/veterinaerarzt/diensttage.html

25. Gesellschaft Schweizer Tierärztinnen und

Tierärzte (2005). Berufsbild Tierärztin/Tierärzt.

Thörishaus: Gesellschaft Schweizer

Tierärztinnen und Tierärzte GST.

26. Artikel 97 van de Nederlandse Grondwet,

geraadpleegd via:

http://www.denederlandsegrondwet.nl/

9353000/1/j9vvihlf299q0sr/vgrndb9f5vzi

27. Ministerie van Defensie bestuursstaf (2010).

Brochure: Nationale operaties en (inter)nationale

noodhulp. Den Haag: Ministerie van Defensie.

28. Ministerie van Defensie (2010, 23-11). Taken:

Nationale Taken. Geraadpleegd via: http://

www.defensie.nl/nationale_taken/introductie/

29. Ministerie van Defensie. Taken: Missies.

Geraadpleegd via: http://www.defensie.nl/

missies/uitgezonden_militairen/

30. Ministerie van Defensie. Taken: Internationale

Reactiemacht. Geraadpleegd via:

http://www.defensie.nl/taken/internationale_

reactiemacht/

NMGT 67 - 1-44

11

JANUARI 2014

31. Ministerie van Defensie. Onderwerpen: CIMIC:

Organisatie 1 CIMIC bataljon. Geraadpleegd via:

http://www.defensie.nl/onderwerpen/cimic

32. Ros A.: (2012). Dierenartsen leveren belangrijke

bijdrage aan buitenlandse missies. Tijdschrift

voor Diergeneeskunde, 137 (7), 464-465.

33. Van der Kloet I.E.: (2011). Provinciale

Reconstructie Teams: de veterinair als schakel

in de reconstructieketen.

Nederl Mil Geneesk T, 64, 108-111.

34. Van Schaik B.: (2011). Nieuw:

West Nile Virus! ….. of niet?

Nederl Mil Geneesk T, 64, 117-120.

35. Landmacht, OOCL Sectie GZHZ, Bobeldijk N.

(2012). HPG: In dienst van de commandant.

(Presentatie)

36. Van Knapen F.: (2011). One Health, one

medicine. Nederl Mil Geneesk T, 64, 93-95.

37. Cates M.B.: (2007). Healthy Animals, healthy

people. Army Medical Department Journal, July

2007, 4-7.

38. NATO (2009) Animal Care and Welfare and

Veterinary Support during all phases of military

deployments.

39. Steltenpool B.A.: (2009). Gastcolumn:

Overpeinzingen van een dierenarts.

Militaire Spectator, 178 (9), 2-3.

40. NATO Standardization Agreement (STANAG):

Welfare, care, and veterinary support for

deployed military working animals.

41. RIVM Emzoo 2011.

42. NATO. Veterinary Guidelines on major

transmissible animal diseases and preventing

their transfer. AMedP-26.

43. Koster J.: (2011). Volksgezondheids- en

veterinaire risico’s door versleep van

pathogenen bij militaire operaties.

Nederl Mil Geneesk T, 64, 121-122.

44. Ministerie van volksgezondheid, welzijn en sport.

LCI richtlijn: Rabies. Geraadpleegd

via:http://www.rivm.nl/Bibliotheek/

Professioneel_Praktisch/Richtlijnen/

Infectieziekten/LCI_richtlijnen/LCI_richtlijn_

Rabies

45. http://web.oie.int/wahis/public.php

46. Ministerie van Defensie. Personeel: Reservisten:

Reservist Militaire Taken. Geraadpleegd via:

http://www.defensie.nl/landmacht/personeel/

reservisten/reservist_militaire_taken/nationale_

operaties

47. Ministerie van Defensie bestuursstaf (2010).

Brochure: Nationale operaties en (inter)nationale

noodhulp. Den Haag: Ministerie van Defensie.

48. Vroegindewey G.: (2007). Emerging Roles of the

US Army Veterinary Service. Army Medical

Department Journal, July-Sept 2007. 8-11.

49. Headquarters, Department of the Army (1997).

Veterinary Service: Tactics, Techniques, and

Procedures. Washington D.C.: Department of

the Army.

50. Van der Kloet I.E.: (2011). Provinciale

Reconstructie Teams: de veterinair als schakel

in de reconstructieketen. Nederl Mil Geneesk T,

64, 108-111.

51. Vogelsang R.: (2007). Special Operations

Forces Veterinary Personnel. US Army Medical

Department Journal, July-Sept 2007. 69-70.

52. Ministerie van Defensie. Functiebeschrijving

Defensie 1.0.0: HFD HPG / STOFF

ARBEIDSHYGIENE. Den Haag: MvD.

53. Ministerie van Defensie. Functiebeschrijving

Defensie 1.0.0: HLP HPG / CH VAU MZ.

Den Haag: MvD.

54. Ministerie van Defensie. CIMIC:

Economy & Employment. Geraadpleegd via

http://www.defensie.nl/onderwerpen/cimic/

economy__employment

55. Smith J.C.: (2007). Stabilization And

Reconstruction Operations: The Role Of The US

Army Veterinary Corps. US Army Medical

Department Journal, July-Sept 2007, 71-80

56. Ministerie van Defensie. Onderwerpen: CIMIC.

Geraadpleegd via

http://www.defensie.nl/onderwerpen/cimic

57. Ministerie van Defensie. Missies: Export van

PRT Expertise. Geraadpleegd via:

http://www.defensie.nl/missies/actueel/isaf/

2010/08/16/46171100/Export_van_PRT_

expertise

58. Ministerie van Defensie (2007). Eindevaluatie

Provinciaal Reconstructie Team Baghlan. Den

Haag: Ministerie van Defensie.

OORSPRONKELIJK ARTIKEL

Het begint allemaal met hygiëne

door Hanneke Wijnker

Interview met prof. dr. Frans van Knapen

“Ik vraag altijd aan mijn eerstejaarsstudenten of ze weten wat handen wassen is. De functie van water, zeep,

desinfecteren? Dan zie je ze kijken. Maar goed handen wassen is zó belangrijk. Bij ‘ons’ telt maar één woord:

hygiëne.” ‘Ons’ is de Divisie Veterinaire Volksgezondheid van de Faculteit Diergeneeskunde Universiteit Utrecht,

de enige opleiding in Nederland voor dierenartsen. Aan het woord Frans van Knapen, hoogleraar

Levensmiddelenhygiëne en Veterinaire Volksgezondheid.

Veterinaire Volksgezondheid (VPH)

De discipline veterinaire volksgezondheid bevindt zich op het raakvlak tussen

diergeneeskunde en humane geneeskunde en richt zich in het bijzonder op microbiële

en niet-microbiële contaminanten (water, bodem, lucht) die een potentieel risico

vormen voor de mens. De Divisie Veterinaire Volksgezondheid (VPH) vormt een

onderdeel van het interfacultaire Institute for Risk Assessment Sciences (IRAS) van

de Universiteit Utrecht. Binnen de drie hoofdactiviteiten onderwijs, onderzoek en

dienstverlening houdt de Divisie zich met name bezig met de bescherming van de

mens waar die mogelijk in gevaar komt door contacten met dieren (zoönosen) of het

nuttigen van voedingsmiddelen (vlees, vis, eieren, melk, kaas).

Afb. 1: Prof. dr. Frans van Knapen.

Zijn taak bij de faculteit zit er na

bijna negentien jaar zowat op. Op

13 december 2013 was zijn

afscheidssymposium. Dan heeft hij op

het gebied van de veterinaire

volksgezondheid een hoop bereikt.

Eén van zijn belangrijkste verdiensten?

“Dat er al weer zes dierenartsen in de

krijgsmacht actief zijn. Niet op fulltime

basis, maar wel als reservist. Daar ben

ik echt apetrots op. Er zitten nu

dierenartsen die het leuk vinden om

met gezondheidsbescherming bezig te

zijn. Er is weer goed toezicht.

Overigens had ik dat nooit alleen voor

elkaar kunnen krijgen. Vanuit Defensie

heb ik veel hulp gehad van reserve

kolonel-dierenarts Bas Steltenpool.

En vóór mij is heel veel voorbereidend

werk gedaan door prof. dr.

David Mossel, emeritus hoogleraar

Voedingsmiddelenmicrobiologie bij de

Faculteit Diergeneeskunde. Hij was

adviseur bij Defensie en na zijn

overlijden, heb ik zijn taak

overgenomen.”

Gezondheidsbescherming

Frans van Knapen is indertijd gevraagd

voor de functie van hoogleraar

Levensmiddelenhygiëne en Veterinaire

Volksgezondheid. “Ik heb de functie

aanvaard op één voorwaarde: dat het

vak aangepast zou worden aan de

moderne tijd en dat het niet meer over

vleeskeuring zou gaan, maar over

veterinaire volksgezondheid. Voor

dierenartsen was volksgezondheid

bijna hetzelfde als vleeskeuring. Maar

vleeskeuring had helemaal geen effect

meer, want sinds 1994 zitten er geen

zieke dieren meer in de voedselketen.”

Die aanpassing had alles te maken

met waar hij vandaan kwam. Van

Knapen had namelijk twintig jaar bij het

RIVM gewerkt. Daar hield hij zich

vooral bezig met zoönosen,

infectieziekten die overgedragen

kunnen worden van dier op mens.

“En dan gaat het niet alleen over vlees,

melk en eieren, maar ook over bodem,

water en lucht. Infectieziekten

verspreiden zich op heel veel manieren

en een dierenarts weet als geen ander

hoe hij met de risico’s om moet gaan.

Zijn taak is gezondheidsbescherming,

dat wil zeggen dieren, en daarmee ook

mensen, gezond houden.”

Exotische bacterie

Is gezondheidsbescherming voor

iedereen in ons land belangrijk, voor

militairen is bescherming van de

volksgezondheid zo mogelijk nog

belangrijker. Van Knapen heeft er jaren

energie in gestoken om Defensie

daarvan te overtuigen. Waarom? De

taken van de landmacht, luchtmacht,

marine en marechaussee liggen

tegenwoordig vooral buiten Nederland.

Zo zijn er missies geweest in

Afghanistan (Kunduz en Uruzgan),

Congo, Irak, Bosnië, Libië, Soedan en

Tsjaad. De antipiraterijmissie in

Somalië loopt nog. Dit is stressvol

werk, de militairen zitten er vaak met

veel op een hoopje en hun

leefomstandigheden zijn niet zoals ze

die in Nederland gewend zijn. “Als je

dan weet dat we in Nederland al aan

de diarree kunnen gaan omdat we

gewoon onze handen niet goed

wassen, dan kun je je voorstellen hoe

gemakkelijk daar iemand flink ziek kan

worden van een exotische bacterie.

Bijvoorbeeld van de geit van de lokale

markt die zo grappig is als mascotte.

Daarom is het heel handig als je

mensen bij je hebt die je kunnen

NMGT 67 - 1-44

12

JANUARI 2014

helpen met het zoeken van een plek

waar je veilig je kamp op kunt zetten,

die alles weten over veilig voedsel en

veilig water, van welke beesten je af

moet blijven, die alles weten over

hygiëne en wat je moet doen als je met

veel mensen langere tijd bij elkaar

bent. Dat zijn de HPG’ers. Die zorgen

ervoor dat de mensen gezond blijven.”

HPG staat voor Hygiëne en

Preventieve Gezondheidszorg en is

onderdeel van de Militair

Geneeskundige Dienst.

Ogen en oren