Domain Theory

Domain Theory

Roberto Poli

Domains—Domains—Domains

We need domain theory for the same reasons science is developed into different branches: Reality is too complex to be understood ‘at a stroke’

The only way we have found to develop our understanding of reality is to fragment it into separate parts (our domains) and to proceed by analyzing one part at a time

The guiding idea

Segment the whole of reality into classes of connected phenomena

Phenomena occurring within each class are more homogeneous than are phenomena pertaining to other classes, so that the task of explaining their behavior should be more easily accomplished

Domain theory cannot be limited to science, however

Many domains are only remotely, if at all, connected to science

(common sense, behavioral practices, aesthetic experiences, etc)

Questions about Types of Domains

Are there different types of domain?

How many different types should be distinguished?

What is their internal organization?

How are the different types related to each other?

Is there any methodology which helps to establish a domain’s boundaries?

Domains

Sharply defined domains with well-defined boundaries

Blurred domains, depending on highly pragmatic decisions/interests

Many domains present intermediate values between these two cases

Underdeveloped state of the theory of domain

Domain

Types of domain

Domain in the proper sense (e.g. biology)

Sub-domain or facet frameworks (e.g. genetics)

Cross-domain (e.g. medicine)

Micro-domain (e.g. edible substances)

I shall presented the first two types in some detail

Main difference between domains in the proper sense

(first case) and all the other cases. This explains why finding a criterion with which to distinguish proper domains from the other domain-types is mandatory

The Framework

Levels of reality distinguish types of entities (material, psychological, social entities)

Levels of Reality

Wholes

Wholes distinguish types of structures

(aggregate, system)

Domain Theory

A level of reality usually requires a vast array of categories. I would like to see whether domains can be organized around some basic types of entities

A Proposal

Domain

1

= Categorically closed, maximal partition of reality

Categorically closed = even if the domain’s entities may be

existentially dependent on lower and/or adjacent entities, they nevertheless require a categorical framework different from the one used to understand the entities of the existentially supporting levels

Organisms require chemical entities (molecules) which require physical entities (atoms) as their ‘matter’. However, the frameworks needed to understand biology, chemistry and physics are different

Maximal partition of reality = the domain includes all the entities that are selected by its categorical framework

Whatever the merits of this proposal, it entails that not any

partition whatsoever is a domain (in the proper sense)

From Levels to Domains

Hypothesis: For any domain, some of its entities are more characterizing than others

Biology (simplified)

Biological entity (BE)

Living entity (LE)

Organism (OR)

Biological Entity (BE)

BEs delimit the field of biology

BEs include biological items such as the nucleus of a cell, the membrane of a cell, its organelles, DNA, mRNA, and urine.

None of these is a properly living entity: they pertain to parts of a living entity or to their products or waste (urine)

BEs also include non-biological items such as the nests made by birds and the pebbles eaten by chickens. Some nests are made of twigs and other matter; others are f.i. deliberately made holes in the ground. Holes and pebbles are not

‘biological’ entities in any proper sense of the term. They pertain, however, to the field of biology, because they are constructed by authentically biological entities (organisms) or are needed by them. We can consider them as entities with a primary physical nature and a secondary biological one

Living entities (LE)

LEs constitute a specific class of BEs. All LEs are systems, while not all BEs are. Furthermore, LEs are metabolic systems, i.e. LEs are entities that can survive if appropriate nutrients are provided. Cells , tissues and organs are cases in point.

Organisms (OR)

ORs are autopoietic LEs, i.e. LEs able to produce the BEs of which they are composed. Two main types of ORs should be distinguished: unicellular and multicellular

The distinction between unicellular and multicellular entities requires to articulated along the customary distinction between prokaryotes and eukaryotes. The former are unicellular entities whose genome is not enclosed within the cell’s nucleus, while the latter can be either unicellular or multicellular and are such that their genome is enclosed within the cell’s nucleus

A cell which is a unicellular organism is a BE, a LE and an

OR. A multicellular organism as a whole is a BE, a LE and an OR. However, the cells of multicellular organisms are living entities but they are not organisms (a liver cell is a living entity but not an organism)

Caveat!

If one subtracts LEs from the field of the biological BEs, what remains coincides with the field of organic chemistry. This shows the link between biology and its underlining level of reality

However, there are differences. The subtraction of living entities modifies the situation in such a way that a number of questions become unanswerable. Even if urine is a purely chemical substance (well, a mixture of substances), how can one explains its presence without taking organisms and their metabolism into consideration?

The questions asked from within organic chemistry and those asked from within biology are different. This shows that they are different domains. The reason for their difference lies in the entities grounding their specific levels of reality: molecules for chemistry and cells for biology

Facets

The next step after establishing the core categories is to determine the dimensions of analysis of the domain’s entities. This is where facet analysis comes in

With reference to the domain of biology, two series of facets follow

The first series lists the characteristics from which an organism as an actually given object-type can be seen.

The second series of facets lists all the other characteristics , those not focused on the organism as an actually given object-type

Facets, first series

The first series is centred on the governing concept of organism as an individual whole and lists the “viewpoints” from which organisms as an actually given object can be seen. One can then consider at least the following four cases: Classification (Taxa), Structure, Function, Behavior

Classification models biological taxonomies

Structure applies part-whole analysis to cells and organisms, for both parts, organs and tissues. Traditionally this type of analysis is called cytology for cells and anatomy for multicellular organisms

Function corresponds to what is traditionally called physiology and model the working of the part descriptively listed by the previous facet of the organism’ structure. In the case of the facet of functions, (serious) variations are usually called pathologies (to be further distinct between intra- and inter-systemic pathologies)

Behavior deals with the organism’s actions. It requires consideration of the organism’s environment (ethology)

Facets, second series

The second series of facets list all the other viewpoints, those not focused on the organism as an actually given object

Two main cases derive

Facets focussed on the organism as a whole. These may include the growth, development and reproduction of organisms

Analysis of the various parts of this whole, e.g. the genes governing the production of the organism

Facets, again

Objects pertaining to different domains may require different facets

Establishing a universal list of facets will guide analysis and help in maintaining greater methodological coherence across domains

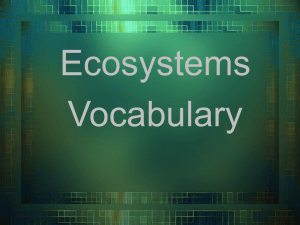

Facets—facets—facets

By comparing and integrating the ancient Aristotelian list of categories with the list produced by the Classification

Research Group, one obtains a 16-entry list

A 16-dimension analysis, however, is both difficult to manage and cumbersome from a cognitive point of view

Grouping the 16 dimensions into some groups provides an environment easier to understand and manage, and helps in adding consistency controls

The Table of Facets

Item

Name

Analysis

Kind

(hyperonym)

Ambit

(type of)

Structure

Property

Matter

Process

Internal pr

Operation

Patient

Function

Outcome

By-product

Agent

Context

Context

(related to)

Spacetime

Space

Time

Comments

Levels of Reality

Wholes

Domain Theory

Item

Name

Analysis

Kind

Ambit

Structure

Property

Matter

Process

Internal pr

Operation

Patient

Function

Outcome

By-product

Agent

Context

Context

Spacetime

Space

Time

Unbalanced groups of categories

Relevance of the group of processes

Context underrepresented (may depend on not having discussed ‘wholes’)

Entries of the groups ‘analysis’ and ‘process’ are mutually connected