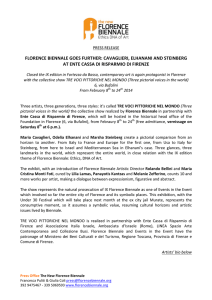

Download the press kit

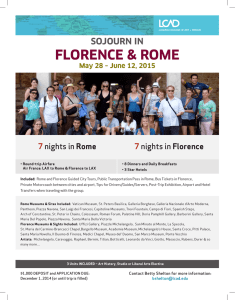

advertisement