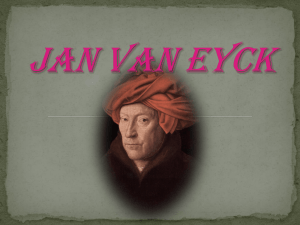

Northern Renaissance

advertisement

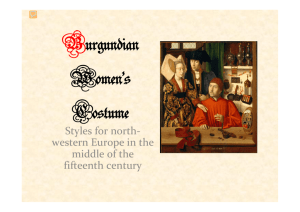

The Northern Renaissance in Holland, Flanders, Belgium and Germany Jan Van Eyck Roger Van der Weyden Hugo Van der Goes Albrecht Durer Hans Holbein Hieronymus Bosch Key Terms Detail Precision Symbolism In Northern Europe, the Renaissance came later than it did in Italy, and it progressed more slowly. In Italy, artists had the ruins of classical Roman and Greek culture all around them and took their inspiration from these works. In the north, artists continued to develop the International style, which had developed in the late Medieval period and was characterized by precision, detail, grace, and elegance. Artists in northern European countries spent countless hours painting the delicate design on a garment, the leaves on a tree, or the wrinkles on a face. At the same time, symbolism, which was so important in Gothic art, grew even more important. Many of the details placed in a picture had special meanings. For example, a single burning candle meant the presence of God; a dog was a symbol of loyalty; and fruit signified the innocence of humanity before the Fall in the Garden of Eden. (Mittler. Art in Focus) Look for these symbols and others in the painting Giovanni Arnolfini and his Bride. How many can you identify? Suggest meanings for the various symbolic elements in the painting, the placement of the figures, the clothing, the room’s furnishings. Besides the dog, the candle, and the fruit, there are additional symbolic objects in this famous painting. The shoes, seen at bottom left, signify that, as they receive the sacrament of marriage, these people are in the presence of God, and therefore standing on holy ground. (Moses was told the remove his shoes when he encountered God in the burning bush, and the young couple do the same). The broom that hangs from the bedpost is a symbol of domestic housekeeping; these two people are setting up a home that they will look after together. The mirror on the far wall of the room shows the reflections of two people, one of whom is Van Eyck himself; these figures are the witnesses of the marriage of Arnolfini and his bride. Just above the mirror, Van Eyck has signed his name in ornate script, with the message: Jan Van Eyck was here, 1434. If you consider the painting as a visual document, recording the marriage, then this is Van Eyck’s signature, as a witness to the event. Signs of wealth Arnolfini would have demanded that his wealth and status were obvious when he commissioned Van Eyck to paint this double portrait. The two figures are very richly dressed; despite the season both their outer garments, are trimmed and fully lined with fur. The furs may be the especially expensive sable for him and ermine or miniver for her. Both outfits would have been enormously expensive, and appreciated as such by a contemporary viewer. The interior of the room has other signs of wealth; the brass chandelier, the oranges, the elaborate bed-hangings, and the carvings on the chair and bench against the back wall. Another sign of wealth is the small Oriental carpet on the floor by the bed; many owners of such expensive objects placed them on tables, as they still do in the Netherlands; this couple can afford to walk on their carpet. (Wikipedia) The placement of the two figures suggests conventional 15th century views of marriage and gender roles – the woman stands near the bed and well into the room, symbolic of her role as the caretaker of the house, whereas Giovanni stands near the open window, symbolic of his role in the outside world. Giovanni looks directly out at the viewer, his wife gazes obediently at her husband. His hand is vertically raised, representing his commanding position of authority, whilst she has her hand in a lower, horizontal, more submissive pose. However, her gaze at her husband can also show her equality to him because she is not looking down at the floor like lower class women would. They are part of the Burgundian court life and in that system she is his equal not his subordinate. (Harbison, Craig) Jan van Eyck – The Adoration of the Lamb - 1432 Van Eyck - Adoration of the Lamb This painting is made up of 12 panels and stretches four and a half metres across in total. It depicts a sacrificial lamb on an altar at the centre of the composition, a symbolic representation of Jesus. The fountain at the bottom of the picture represents the healing water of baptism. Clarity and Realism The light in van Eyck’s painting is crystal clear. It allows you to see perfectly the colour, texture, and shape of every object. The details are painted with extraordinary care. The soft texture of hair, the glitter and luster of precious jewels and the richness of brocade are all painted with the same concern for precision. Every object, no matter how small or insignificant, is given equal importance. This attention to detail enabled van Eyck to create a special kind of realism – a realism in which the colour, shape, and texture of every object were painted only after long study (Mittler. Art in Focus). Rogier Van der Weyden – Descent from the Cross Van der Weyden, like van Eyck, was concerned with detail, but he took the development of painting in Northern Europe forward with some new ideas. In his Descent from the Cross, we see more emotion, and a greater concern for design, or organization, than we find in van Eyck’s pictures (Mittler. Art in Focus). Notice the repeating curved axis lines: Christ’s body forms an S curve, which is repeated in the curve of his fainting mother. The two figures on either side bend inward and direct your attention to Christ and his mother. The figures fill the shallow space, allowing the viewer to see the highly individual expressions on the faces of the figures. Van der Weyden was notable for the emotionalism of his paintings. The two hands at the centre of the painting, Mary’s left, and Jesus’ right, are close, but not touching, suggesting the gulf that has opened between the living and the dead. Rogier Van der Weyden Portrait of a Lady Van der Weyden’s portrait is remarkable for its psychological insight. He has been able to convey her reserve, and quiet dignity quite clearly. Hugo Van der Goes The Adoration of the Shepherds Van der Goes combined the emotionalism of Rogier van der Weyden with the realistic detail of Jan van Eyck. But he made an addition of his own: He was not afraid to alter or distort nature or proportion if it would add to the emotionalism of his picture (Mittler. Art in Focus). In his Adoration of the Shepherds, we see distortions in the proportions of the various figures, with the angels in the foreground much smaller than the figure of Mary. This painting was sent to Florence, Italy, soon after it was completed, and made a deep impression on the Italian artists who saw it. What excited them most was the portrayal of the three shepherds, who are not elegant noblemen, but ragged peasants. No one had dared to depict religious scenes like this before. Albrecht Durer Self Portrait Albrecht Durer – Stag Beetle Albrecht Durer Praying Hands Albrecht Durer Melancholia Albrecht Durer Knight, Death and the Devil Hieronymus Bosch The Garden of Earthly Delights Hieronmymus Bosch Death and the Miser Pieter Brueghel The Parable of the Blind Pieter Brueghel Peasant Wedding Pieter Brueghel Returning Hunters Pieter Brueghel Hans Holbein Edward VI as a Child Hans Holbein King Henry VIII Hans Holbein Anne of Cleves