Teaching Prognostication

advertisement

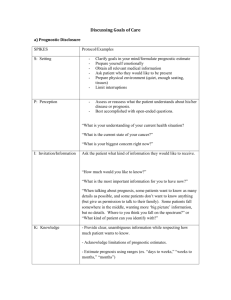

Prognostication Eric Widera, MD What is Prognostication? • The Two parts: 1. Estimating the probability of an individual developing a particular outcome over a specific period of time (prognosis). 2. Communicating the prognosis with the patient and/or family. Overview of Our Sessions Objectives • 2 parts – Describe one way to teach learners how to estimate prognosis in the clinical settings – Name one method of communicating prognosis… Challenges to Prognostication in Older Adults • Younger patients with cancer: clearer trajectory – Value of disease specific prognostication • Older adults: – Absence of dominant terminal condition – age + functional + cognitive + multimorbidity Ways to Prognosticate in Elderly Clinical Judgement Shortcomings of Clinical Predictions • Tend to overestimate patient survival by a factor of between 3 and 5. • Tend to be more accurate for very shortterm prognosis than long-term prognosis. • Influenced by relationships – The length of doctor patient relationships increases the odds of making an erroneous prediction. Life Tables US Life Tables www.eprognosis.org Great Variation in Life Expectancy for People of Similar Ages Life Expectancy for Women Years Age (years) Walter LC. JAMA 2001;285:2750-56 Prognostic Indices Prognostic Indices • Physicians can use prognostic indices to lend confidence to their judgments about prognosis – National survey of 697 physicians: 57% felt inadequately trained in prognostication • Prognostic indices provide an objective measure to support clinical intuition • Combining clinical estimates with prognostic indices results in more accurate estimates than either alone. Christakis & Iwashyna, Arch Intern Med 1998 Prognostic Information is Hard to Find • Generally, less than 30% of medical textbook chapters discuss prognosis (instead focus on etiology, diagnostic criteria and treatment) • Tools developed for mortality prediction in older people may be difficult for busy clinicians to remember or use Communicating Prognostic Information Elizabeth Eckstrom, MD, MPH Oregon Health & Science University Do Patients Want to Know? Those who did not have a prognosis conversation were asked, do you want one? Patients: 55% yes 40% no 5% I don’t know Caregivers: 75% yes 23% no 2% I don’t know Fried et al. JAGS 2003 Ahalt et al, JGIM 2011 SPIKES- A Tool for Communication • • • • S—SETTING UP the Interview P—Assessing the Patient's PERCEPTION I—Obtaining the Patient's INVITATION K—Giving KNOWLEDGE and Information to the Patient • E—Addressing the Patient's EMOTIONS with Empathic Responses • S—STRATEGY and SUMMARY S—SETTING UP the Interview • Be sure it is happening in a quiet, undistracted environment • Include family members whenever possible (if having the discussion in clinic, ask if anyone else should be present, and postpone the discussion till everyone can be there or utilize conference calling) – “At our next visit, I would like to talk about your health and the ways we can go forward with your care. Is there someone who you think should be at this meeting?” • Connect with the patient and family first P—Assessing the Patient's PERCEPTION • Ask open-ended questions to ensure you know what the patient and family currently understands about their medical issues and prognosis – “It seems things are getting a little harder for you. What is your sense of where we are going with your health?” – “What do you understand about your current health?” • Ask if they would like more details about “what to expect next” – Some people don’t want to know, or want you to speak with their family but not themselves. – “Some patients feel it is important to know the all the details of their illness, prognosis, and treatment options; others don’t and want others to make decisions for them. How do you feel?” I—Obtaining the Patient's INVITATION Inquire about preferences “Some people can deal with that knowledge and some people can’t” (AA man age 67) Be direct, empathic, take time “Many times the truth has to be softened. It cannot be so abrupt because that causes harm to people” (latino man age 86) Recognize uncertainty “A good doctor would say, ‘look, I believe from all the tests and all you’ve got about a so-and-so much to live. But then again, we don’t know. We don’t know.” (white man age 76) K—Giving KNOWLEDGE and Information to the Patient • Speak simply and slowly – “If there were 100 patients in your father’s current condition, in 5 years roughly 80 would die and 20 would survive. I am basing this on his advanced heart failure and his worsening functional status” • Periodically check for understanding • Frame conversation in light of patient goals • Consider using a range of time – – – – Hours to days Days to weeks Weeks to months Months to years E—Addressing the Patient's EMOTIONS with Empathic Responses • Consciously observe emotions • Name the emotion to yourself- if you are not sure what you are observing, ask – “You seem a little surprised by this news. Is it different from what you were expecting?” • Express empathy with the emotion – “I can understand that this news is a little unsettling when you have been doing everything you can to live longer.” – “I wish I didn’t have to tell you there isn’t much time left. May I help communicate this news to other family members who can’t be here today?” S—STRATEGY and SUMMARY • Review strategies to ensure best quality of life possible – “Considering how important being pain free and remaining at home appears to be for you, I recommend that we…” • Solicit patient and family feedback • Establish a future “check in” date to see how things are going – My patient story- Pulmonary HTN, CHF, hyponatremiaafter she outlived the prognosis I gave her (at age 95), we started from scratch “ Clinicians should…offer to discuss the overall prognosis… for patients with a life expectancy less than 10 years or at least by…85 years of age” NEJM 2011