Public Health Measures

advertisement

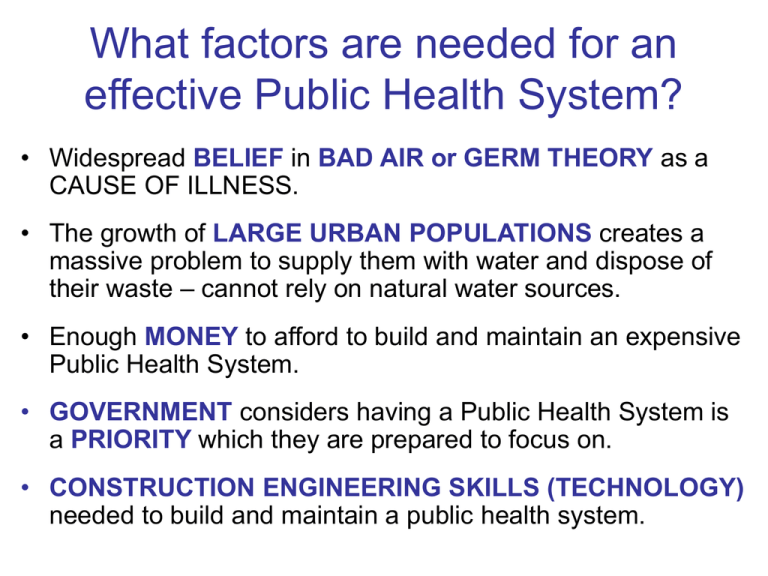

What factors are needed for an effective Public Health System? • Widespread BELIEF in BAD AIR or GERM THEORY as a CAUSE OF ILLNESS. • The growth of LARGE URBAN POPULATIONS creates a massive problem to supply them with water and dispose of their waste – cannot rely on natural water sources. • Enough MONEY to afford to build and maintain an expensive Public Health System. • GOVERNMENT considers having a Public Health System is a PRIORITY which they are prepared to focus on. • CONSTRUCTION ENGINEERING SKILLS (TECHNOLOGY) needed to build and maintain a public health system. PUBLIC HEALTH BEFORE THE ROMANS Very limited Public Health provision • Widespread BELIEF in the GODS (RELIGION) and the THEORY OF THE FOUR HUMOURS as CAUSES OF ILLNESS which would not have favoured the setting up a Public Health System. Egyptian idea of CHANNELS AND BLOCKAGES (based on irrigation) could have developed into a justification for public health, but was not taken up by the Greeks – too closely linked to Egypt’s unique reliance on the Nile. • Most people lived in small, rural communities. URBAN POPULATIONS were generally SMALL by modern standards, even in the Egyptian and Greek civilisations, and therefore could rely on relatively limited water supply and waste disposal systems. • Ancient Egypt and Greece were relatively RICH societies – they had enough MONEY to build and maintain public health systems. • GOVERNMENT leaders generally did not see public health as a priority. Water supply systems were developed simply to meet local needs and were not based on long term urban planning. • CONSTRUCTION ENGINEERING SKILLS (TECHNOLOGY) could produce works on a grand scale, using a developing geometry (e.g. Egyptian pyramids & Greek temples) but only stone & wood as building materials. These skills were usually used on religious & military building projects. ROMAN PUBLIC HEALTH c.200BC - c.AD500 Effective Public Health provision • Widespread BELIEF in BAD AIR as a CAUSE OF ILLNESS, but the GODS (RELIGION) and the THEORY OF THE FOUR HUMOURS were also common beliefs which would not have favoured the setting up a Public Health System. • Rome had a LARGE URBAN POPULATION – about a million people by 1st Century AD, much larger than previous ancient cities – the River Tiber which flowed through the city certainly could not have provided enough water for everyone on its own. Many other cities (e.g. Alexandria) & towns across the empire needed or could benefit from the same measures used in Rome. Public fountains, toilets & bathhouses meant everyone, rich and poor, could benefit from the public health measures. • The Roman Empire very RICH – Roman emperors had enough MONEY to build and maintain an effective public health system, e.g. Huge Baths of Caracalla (3rd Century AD). The use of slaves in the labour force also kept costs down. • GOVERNMENT (under the EMPEROR) saw Public Health as a priority. Emperors could show how they cared for the people by maintaining & improving the public health system (e.g. Government official, Frontinus, in charge of Rome’s system in 1st Century AD). The empire also depended on the ARMY for its survival, so emperors had to ensure the legionaries were healthy & ready to fight at all times. • CONSTRUCTION ENGINEERING SKILLS (TECHNOLOGY) were advanced in Roman times – as well as stone & wood, the Romans also had tile bricks & concrete from limestone as building materials. They mastered building with arches, and these were used in all aspects of the public health system – aqueducts (11 supplied Rome in 2nd Century AD – total combined length - 300 miles), sewers (Cloaca Maxima (The Great Sewer, which emptied into the Tiber)) and vaulted ceilings of bathhouses (Baths of Caracalla; Baths of Diocletian). Roman military manuals gave clear instructions how to build forts for legionaries (who were trained to be builders as well as soldiers) to ensure they were healthy environments (e.g. Vegetius, On Military Matters, 5th Century AD) – sometimes included hospitals (valetudinarium). MEDIEVAL PUBLIC HEALTH c.500 – c.1500 (CHRISTIAN MEDICINE IN THE WEST) Very limited Public Health provision • Widespread BELIEF in GOD (RELIGION) and THEORY OF THE FOUR HUMOURS as a CAUSE OF ILLNESS. The Roman idea of BAD AIR was still believed in by some, but was not the most popular belief. • Most people lived in small, rural communities. URBAN POPULATIONS were generally SMALL by modern standards, apart from London, but living conditions could be dreadfully unhygienic: open sewers; cesspits; livestock within towns. • Medieval society was relatively POOR – not enough MONEY to maintain an effective system. • GOVERNMENT was not expected to be involved in medicine, which was controlled by the CHURCH (e.g. ran leper hospitals - St Mary Magdalen, Cambridge). Kings and town councils did more after the crisis of the Black Death (1348), but it was mainly isolated examples, such as donating money to hospitals (Queen Anne of Bohemia supported St Giles Hospital), lead pipes which carried water from River Tyburn into London (13th Century) and more carts for the removal of waste from London (12 by c.1400). • CONSTRUCTION ENGINEERING SKILLS (TECHNOLOGY) were limited in the Middle Ages – wood & stone were the main building materials – could build hospitals modelled on Churches (St Giles Hospital, Norwich) and small scale water supply systems for castles & monasteries. MEDIEVAL PUBLIC HEALTH c.500 – c.1500 (ISLAMIC MEDICINE IN THE EAST) Effective Public Health provision – much continuity from Roman times. • Widespread BELIEF in ALLAH (RELIGION) and THEORY OF THE FOUR HUMOURS as a CAUSE OF ILLNESS. The Roman idea of BAD AIR was still believed in by some, but was not the most popular belief but in the case of the Islamic RELIGION daily ritual washing was required - mosques needed a reliable water supply, so as a factor it did support Public Health provision to a point. • LARGE URBAN POPULATIONS continued to be found across the Middle East, as in the Ancient World, with new Islamic cities (e.g. Baghdad; Cairo; Samara) often including sophisticated water supply and sewage systems as part of their urban planning – Turkish Baths were found throughout the region, a contiunation of the bathhouses of Roman times. • The Islamic East in medieval times was dominated by great EMPIRES (first Arabic; later Turkish & Persian) which were RICH and had enough MONEY to maintain an effective system especially since much more had survived there of the Roman measures (Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire declined slowly between 7th and 15th Centuries). • GOVERNMENT leaders (Caliphs (Arabs) & Sultans (Turks)) often continued the Roman practice of treating public health as a priority – this is reflected in town and palace planning (Caliph’s palace in Baghdad included a bathhouse in 8th Century) and the high status enjoyed by some involved in medicine, e.g. Avicenna was both a government official and a doctor; Rhazes was consulted on where to build a hospital in Baghdad. • CONSTRUCTION ENGINEERING SKILLS (TECHNOLOGY) were limited in the Middle Ages – wood & stone were the main building materials, but advances in mathematics by Muslim scholars contributed to sophisticated building projects, e.g. Baghdad & Samara’s extensive canal systems laid out in 9th Century. RENAISSANCE PUBLIC HEALTH c.1500 – c.1700 Very limited Public Health provision • Continued widespread BELIEF in GOD (RELIGION) and THEORY OF THE FOUR HUMOURS as a CAUSE OF ILLNESS. BAD AIR was becoming a more popular belief. • URBAN POPULATIONS were still generally SMALL by modern standards, apart from London which started to grow dramatically at this time. Living conditions continued to be dreadful. • Renaissance society was relatively POOR but Kings generally were richer than medieval kings – not enough MONEY to maintain an effective system. • GOVERNMENT was not expected to be heavily involved in medicine, but the control of the CHURCH was weakening. Examples of government measures included the construction of New River in 1613 (reign of James I) to supply London with water from springs in Ware and quarantine measures for London enforced during the Great Plague (1665) by the Lord Mayor, under King Charles II: red crosses painted on doors; guards posted at the ends of infected streets; mass burial of dead outside the city at night; doctors dressed in bird-like protective clothing; ‘pesthouse’ hospitals for treating victims; killing of stray cats & dogs – not always successfully enforced, e.g. people did leave the city. • CONSTRUCTION ENGINEERING SKILLS (TECHNOLOGY) advanced from the Middle Ages: wood & stone still common, but bricks increasingly being used. Improvements to pumping equipment had little immediate effect on public health measures – required effective power source, e.g. New River relied on gravity and lead-lined aqueducts. THE TURNING POINT - PUBLIC HEALTH IN THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION c.1750 – c.1900 Eventually set up effective Public Health provision – things got worse before they got better! • Widespread BELIEF in BAD AIR (‘MIASMA’), replaced by GERM THEORY (SCIENCE) (1861 onwards), as a CAUSE OF ILLNESS – BOTH ideas meant a Public Health System made sense. • URBAN POPULATIONS grew massively at this time as a result of the Industrial Revolution (e.g. London quadrupled in size). Living conditions remained dreadful – industrial pollution; poorly built housing; overcrowding; inadequate sanitation; TB & CHOLERA (arrived in 1831 - major epidemics every decade up to 1870s) were the big killer diseases. • Britain was now the RICHEST country in the world (EMPIRE & INDUSTRY) but millions of ordinary people were POOR (from 1834 workhouses provided basic poor relief & limited healthcare) – enough MONEY to maintain an effective system. • GOVERNMENT was slow to get involved in Public Health: LAISSEZ-FAIRE informed public opinion from 1830s to 1870s – national & local governments were reluctant to spend money. A few pioneers, such as EDWIN CHADWICK (INDIVIDUAL), campaigned for governments to do more, but measures were inadequate before the 2nd PUBLIC HEALTH ACT (1875): local councils must have clean water supply; sewers and a district medical officer to oversee it. Chadwick’s 1842 Report; 1st Public Health Act (1848) – voluntary for local councils; General Board of Health (1848-54) - Chadwick; Broad Street Pump Case (1854); The ‘Great Stink’ (1858); Bazalgette’s sewers for London (1865); 1867 Reform Act (extension of right to vote to most working class men – Public Health had to be a PRIORITY from now on) – main examples of gradual advance in government involvement. • CONSTRUCTION ENGINEERING SKILLS advanced dramatically using the new TECHNOLOGY of the Industrial Revolution: steam engines could pump thousands of gallons of water; mass produced bricks & clay pipes to line water pipes & sewers; iron, steel and high grade copper. JOSEPH BAZALGETTE built London’s modern sewer system (1858 – 1865) – unprecedented construction project. More and larger urban hospitals could be built (privately) to treat population – organised under Nightingale’s principles for cleanliness (1860 onwards). THE 20th CENTURY: PUBLIC HEALTH TRANSFORMED • Universal BELIEF in GERM THEORY as a CAUSE OF ILLNESS – CONTAMINATED WATER AND POOR DIET unquestionably causes of infection. • The continued growth of LARGE URBAN POPULATIONS meant that there was still potential for poor living conditions and made hospital and water supply construction continued priorities. • Enough MONEY to afford to build and maintain an expensive Public Health System, including modern hospital facilities (most hospitals were still private charities up to 1948) – Britain has remained a RICH, industrialised country, even after its empire started to decline after World War Two. • GOVERNMENT had accepted the need to provide a modern water supply system by the end of the 19th Century, but was pushed into taking on more and more responsibility for healthcare throughout the 20th Century by: WAR (Boer War 1899 1902; First World War (1914-18); Second World War (1939-45) – highlighted limitations in healthcare provision and made governments make promises to the population to raise morale (incentives); DEMOCRACY (by 1928 all people over 21 could vote – political parties had to appeal to them) and INDIVIDUALS, like ANEURIN BEVAN, who was the determined Labour Minister of Health who brought in the NHS in 1948. Healthcare remains one of the top PRIORITIES for government to this day. 2 main phases extending government involvement: the ‘Liberal Reforms’ (1906-11) and 1948 (1946 National Health Service Act) onwards. • CONSTRUCTION ENGINEERING SKILLS (TECHNOLOGY) needed to extend and improve existing water supply & sewage systems and build and equip large, modern hospitals, containing advanced electronics (e.g. computers, scanners, radiography (X-rays)). Extensive use of modern materials in all this: steel; plastic; rubber; reinforced concrete. • • • • 1902 - Compulsory training for midwives. 1906 - Free school meals provided. (LIBERAL REFORM) 1907 - All births to be notified to health visitor; Schools provide medical checks. (LIBERAL REFORM) 1908 – Old Age Pensions Act (LIBERAL REFORM) • 1911 - National Insurance Act – government unemployment & health insurance introduced for many jobs. New level of government involvement (LIBERAL REFORM) • 1918 - Local authorities to provide health visitors, clinics for pregnant women and infants and day nurseries. 1919 - Housing & Town Planning Act – extended powers of local councils to clear slums and build good quality council houses. 1921 - More government money available for hospitals. All local councils required to set up sanatoria for the care of tuberculosis patients. • • • Second World War (1939 – 1945) The government ran hospitals; ambulance services were set up everywhere and a cheap medical service was set up for everyone; rationing was organised to provide people with a healthy diet. • 1946 - National Health Service Act – sets up the National Health Service: starts in 1948 – a national insurance system (1948) ensures free healthcare ‘from the cradle to the grave’ – it takes over 2688 hospitals (with over 480,000 beds) and leads to a massive increase in the work of General Practitioner surgeries. (KEY INDIVIDUAL: ANEURIN BEVAN) • • • • 1955 - Strict regulation of food sales to stop food poisoning. 1956 - Clean Air Act – strict regulations on air pollution. 1956 - National Childbirth Trust set up to improve the rate of infant survival 1960s - New government programme of building District General Hospitals – hospital medical and surgical treatment will increasingly rely on modern pharmaceuticals (vaccines against polio, measles and rubella developed by 1960s) and advanced technology – radiography (X-Rays); radiotherapy; computers; scans such as ultrasound; endoscopes 1970s - Single issue healthcare campaigns begin, e.g. anti-smoking; promoting healthy diet. 1992 - ‘The Health of the Nation’ initiative sets NHS targets in reducing death and illness from heart disease, cancer, mental illness, HIV/AIDS and accidents. 2007 - Smoking in public places banned. • • • Conclusions about Public Health Provision in 20th Century • Government played a greater role on healthcare as 20th Century went on, building to NHS (1948) - a turning point in 20th Century Healthcare. War and development of democracy in Britain made governments do more. • Main emphasis before the NHS was on advice and preventative measures (e.g. diet) – this was cheap for the government and the people. • Main emphasis after NHS was on treatment and hospitals – money from government, scientific discoveries (e.g. Penicillin) and new technology (e.g. computers) made this possible: people get this free at the point of delivery so are happy to use it (no need to avoid visiting the doctor if there is no charge). • Hospitals grew in size and number – offer more by second half of 20th Century than just doctors, nurses, beds & some effective medicines – important centres of medical practice and training (could do more than ordinary GP surgeries) - seen as the big solution to many health problems. • But advice continued to be an important part of healthcare. By end of 20th Century limits to what hospitals & modern treatments can do had become clear – many health problems best addressed long before it comes to treatments or hospital care and some of big problems facing NHS (e.g. cancer) have been helped but not solved by modern hospitals and treatment: From 1970s advice on how to have a healthy lifestyle has become an increasingly large part of Britain’s public health system, e.g. 2005 – ban on most forms of tobacco advertising; Jamie Oliver’s campaign (2005) to improve the quality of school dinners; Smoking banned in public places (2007). KEY INDIVIDUAL: EDWIN CHADWICK (1800 – 1890) • Senior government official responsible for effective running of local workhouses for the poor and sick – he was concerned about how the government might spend its money more efficiently on better living conditions for workers to prevent so many of them resorting to the workhouses for help when they subsequently became ill. • 1842 Report (Report on the Sanitary Conditions of the Labouring Population of Great Britain) It advised local councils that: drainage & refuse collection should be provided; pure water supply should be provided; a local Medical Officer of Health should be appointed. Chadwick drew on earlier research by Dr William Farr who compiled accurate statistics showing disease was worse where there were bad water/sewage systems & Dr Robert Baker (Poor Law surgeon in Leeds) who had reported on the Cholera epidemic (1831-32) in Leeds & gave vivid descriptions of living conditions & air pollution. • 1848 1st Public Health Act: General Board of Health (London) under Chadwick & some local boards set up. Only recommended that the advice of the 1842 Report be taken up by local government. General Board of Health abolished in 1854 – councils objected to being told what to do by Chadwick, whose zeal and confidence was often seen as intrusive arrogance. • • Chadwick’s campaigning in the 1840s and 1850s did much to raise the issue of Public Health provision among the public, but did little to change things in the short term. The 1875 2nd Public Health Act made compulsory the recommendations of his 1842 Report, which the 1848 Act had only made voluntary, so in the long term his work directly contributed to the most important Public Health reform of the 19th Century. KEY INDIVIDUAL: ANEURIN BEVAN (1897 – 1960) • Aneurin Bevan was a working class son of a miner in South Wales. At the age of thirteen he left school and began working in a local coal mine himself. He soon became involved in the Trade Unions as a talented spokesperson for miners’ working conditions and pay. • In 1929 he became a Labour Party MP. • In 1942 (in the middle of WWII) the government had published the Beveridge Report. It stated that a National Insurance scheme could provide effective healthcare for all. • In 1945 the Labour Party was elected to run the government for the first time. They had promised to improve the welfare of all classes, regardless of wealth if they were elected. • As the new Minister of Health, Bevan was already famous as a determined campaigner for the rights of the working class and wanted the reforms that the government put forward to go much further than anything else previously attempted to help the majority of people in Britain – free healthcare for all for life. • He overcame all opposition to his plans for the NHS from many different groups: the Conservative Party; the Consultants (he “stuffed their mouths with gold”, i.e. promised them high salaries under the new system) and the GPs. The NHS was successfully launched in 1948. • Bevan resigned in 1951 when the government announced that it intended to introduce measures that would force people to pay towards dentures, spectacles and prescription charges. Bevan saw this as an unacceptable retreat from his completely free service.