The World Within

advertisement

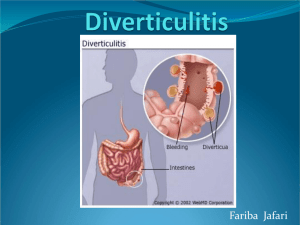

The World Within Micro-organisms in the Digestive Tract: Friends, Foes, and Visitors Janice M. Joneja, Ph.D 2002 The Internal Landscape 2 The Digestive Tract Each site within the digestive tract is designed for optimal function: Digestion of food Protection against invading disease-causing microorganisms Maintenance of healthy balance (homeostasis) In the lower bowel, micro-organisms play an active role in all these functions Sometimes, conditions favour colonisation by microorganisms; others are hostile to their survival The proper functioning of the resident microflora is essential to the health of the body 3 Digestive Enzymes Mouth: Salivary -amylase Lingual lipase Stomach: Acid hydrolysis Gastric pepsins Small intestine: Pancreatic -amylase Lipase Colipase Trypsin Chymotrypsin Elastase Carboxypeptidases Large bowel Microbial metabolism Small intestine: Gall bladder: Bile salts Small intestine: Brush border: Lactase (ß galactosidase) Glucoamylase (-glucosidase) Sucrase-isomaltase Amino-oligopeptidases Dipeptidyl-peptidase 4 Microbial Colonisation Mouth: Saliva Microbial colonisation Esophagus: Micro-organisms present Stomach High acidity Usually sterile Small intestine Neutral or slightly alkaline No resident microbial population Micro-organisms populate lower ileum Large bowel Dense microbial population Mostly anaerobic organisms Rectum Faeces Dense microbial population 5 Microbial Colonisation of the Digestive Tract Factors allowing micro-organisms to live: Body defences (immune system) Determines who stays, who goes Environment: Acidity and alkalinity (pH) Level of oxygen present Diet: Provides nutrients for microbial growth and reproduction Interactions between different types of microorganisms Survival of the fittest 6 Colonisation by Microorganisms The Mouth Micro-organisms enter through the mouth from the external environment Nutrients and salivary secretions in the mouth allow colonisation: Crevices around the teeth Pockets in oral tissues Bacterial plaque on the surface of teeth Numbers and persistence of micro-organisms depends on: Available nutrients Hygiene Speed of transit of contents 7 Micro-organisms in the Esophagus Micro-organisms pass with the oral contents through the esophagus The environment of the esophagus is the same as in the mouth, but it is a conduit, not a “vessel” Material passes through, but does not remain in location, and therefore micro-organisms have no opportunity to colonise the area 8 Micro-organisms in the Stomach In the healthy individual the stomach is sterile The process of eating triggers release of gastric secretions and acid After a meal the pH can be as low as 3.0 Most micro-organisms cannot survive this Gastric secretions and hydrochloric acid kill off most micro-organisms passing from the esophagus Rate of flow of food through stomach also influences microbial survival 9 Micro-organisms in the Stomach Low acidity (higher pH) allows some microorganisms to survive Conditions that may allow bacteria to live: Achlorhydria (lack of gastric acid), especially in the very young, and the elderly Neutralizing substances that reduce acidity of contents, e.g.: sodium bicarbonate other antacids Most common pathogen: Helicobacter pylori 10 Survival of Micro-organisms in the Stomach Rapid movement of food material through before pH is low enough to kill them: Before a meal, pH of stomach is 4-5 Drops to pH 3 while eating Rate of flow of stomach contents influenced by: Composition of meal: Fat passes through slowly Liquid passes through quickly Micro-organisms that survive through the stomach pass into the small intestine 11 Micro-organisms in the Small Intestine Very few micro-organisms live in the first part of the healthy small intestine Numbers increase as the digesta passes into the terminal ileum Conditions that influence microbial multiplication: Rate of flow of digesta: Flow rate greatest at the beginning Slows as material reaches distal end Normal length of time food material takes to transit small intestine: 3-4 hours Water is absorbed Consistency is more solid and allows organisms to stay in place long enough to multiply 12 Micro-organisms in the Small Intestine Under normal circumstances several processes inhibit adherence and colonization in the small intestine, and kill micro-organisms surviving from the stomach: Mucus coats bacteria and disallows contact with the intestinal wall Antibodies, especially secretory IgA, neutralize bacteria Lysozyme in secretions is bactericidal (kills bacteria) Bile salts are bactericidal 13 Micro-organisms in the Small Intestine Micro-organisms can colonise the small intestine and cause infection if they can adhere to the intestinal wall Usually, contents pass through too rapidly to allow this Some situations may predispose to colonization: Motility disorders that interfere with the normal passage of material through Material becomes lodged within tissue pockets (diverticulae) 14 The Large Bowel Most of the micro-organisms that colonise the human body live and thrive in the large intestine Digesta from small intestine enters the caecum where microbial activity begins in earnest As the contents pass from the caecum to the rectum, microbial numbers increase dramatically Adult eating typical Western diet: Total contents: 220 grams dry weight Bacterial dry matter: 18 grams 15 Micro-organisms in the Large Bowel Contents of the large bowel pass from the body as faeces Micro-organisms in faeces same as in terminal part of large bowel Bacteria in faeces: Approximately a trillion per gram dry weight The longer the material remains in the colon, the greater the number of micro-organisms Several hundred different microbial species About 99% of these belong to only 30-40 species 16 Micro-organisms in the Large Bowel Food material remains in the colon approximately 70 hours Inter-individual variation: 20 - 120 hours Many species multiply rapidly: some double every twenty minutes Type and species of micro-organisms is surprisingly stable for each individual Even when infection changes the nature of the species, after pathogens are removed, microflora tends to revert to its original composition 17 Micro-organisms in the Large Bowel Conditions that influence type and numbers of micro-organisms: Amount of oxygen available (many are strict anaerobes and are killed by exposure to oxygen) Competition for nutrients Type of nutrients available Type of micro-organisms present: Organisms that can break down food material and use nutrients fastest will multiply fastest Confined space Organisms that multiply fastest, crowd out others 18 Micro-organisms in the Large Bowel Inter-Species Competition Space and nutrients are limited Species that break down and use available nutrients most efficiently achieve the highest numbers Advantage to species that can: Use substrates most other species cannot process Use waste products of other species, e.g. Hydrogen sulphide Organic acids 19 Source of Nutrients in the Large Bowel Material that has not been completely digested and absorbed in the small intestine: Food matter consumed in diet Cells and tissues sloughed off from digestive tract Enzymes and other material from body processes such as: saliva intestinal secretions such as mucin blood cells Dead micro-organisms 20 Micro-organisms in the Large Bowel Nutrient Substrates Most important nutrient substrates are: Carbohydrates Starch Plant storage material Non-starch polysaccharides (dietary fibre) Plant structural material Oligosaccharides (long chain sugars) From partial digestion of carbohydrates Sometimes disaccharides (sugars) Most are broken down in small intestine Proteins Diet Body secretions, including digestive enzymes Dead micro-organisms 21 Microbial Use of Material in the Large Bowel: Carbohydrates Majority of bacterial species in the large bowel act on carbohydrates Carbohydrates entering the colon of the average adult eating a Western diet per day include: Dietary fibre…………………………12 grams Undigested starch…………………30-40 grams Material from the digestive tract (mucins, enzymes and dead microorganisms)…………………...……….3-4 grams 22 Carbohydrates Dietary fibre Structural parts of plants Have beta-glycosidic linkages between molecules Indigestible by human enzymes Includes: Pectin Cellulose Gums Beta-glucans Fructans 23 Dietary Fibre Usually separated into two types depending how it interacts with water: Soluble fibre: Forms gel or gum Insoluble fibre: Remains unchanged in water Both types present in plants, e.g in legumes: Hard outer skin is insoluble type Inner “pulse” higher in soluble type Cooking and processing does not change the nature of fibre 24 Carbohydrates Starches Previously thought all starch was digested and absorbed in the small intestine Enzymes break alpha-glycosidic linkages between molecules Recent research shows 15%-20% of dietary starch passes undigested into the colon from high starch foods such as: potato pasta rice banana grains (wheat, corn) 25 Starch Undigested starch is called “resistant” starch Starch that is readily digested and absorbed in the small intestine is called “non-resistant” Resistant starch is resistant to digestive enzymes Passes into the colon where it is fermented by gut microflora Unlike fibre, resistant starch is affected by cooking and processing 26 Resistant Starch Process of digestion in the small intestine can be speeded up by cooking - starch is gelatinized Cooling causes a process of crystallization (retrogradation) that renders the molecules non-digestible by enzymes Undigested material passes into the large bowel Freezing and drying can also cause changes in starch that makes it resistant to digestion Research on contents of ileostomy bag 27 Comparison of Dietary Starch A comparison of dietary starch: a) Fed b) Recovered after digestion in the small intestine Food Starch Fed (grams) Starch Recovered (grams) Percentage Starch Recovered (%) White bread 62 1.6 3 Oats 58 1.2 2 Cornflakes 74 3.7 5 Banana (raw) 19 17.2 89 Potato freshly cooked cooled reheated 45 47 47 4.5 5.8 3.6 3 12 8 Englyst and Kingman 1994 28 Factors Affecting Amount of Starch in the Colon Physical accessibility Cell walls of plant cells entrap starch Prevents its swelling and dispersion Delays or prevents digestion by enzymes Includes whole grains, nuts, seeds: vegetables with “skins”: sweet corn, peas, beans partly milled grains and seeds: “whole grain” breads and cereals If the rigid structures of the plant are physically removed, more of the alpha-glycosidic bonds of the starch are exposed to the action of enzymes in the small intestine 29 Factors Affecting Amount of Starch in the Colon Cooking Disrupts starch granules Facilitates digestion by enzymes in saliva and the small intestine When foods with a high level of resistant starch are eaten raw, more undigested starch passes into the colon e.g. Banana Retrograded starch increases on cooling: eat foods with high level of resistant starch when it is hot 30 Factors Affecting Amount of Starch in the Colon Chewing Amylase (ptyalin) in saliva is first enzyme to start process of starch digestion The more the food is chewed, the greater the exposure of the starch to enzymes in the mouth and the small intestine Speed of transit of food The faster the food transits the small intestine, the less exposure to enzymes High fat slows transit High fluid (water with the meal) speeds the transit 31 Oligosaccharides Polymers of glucose 3 - 8 hexose units in length Exist in plant materials as oligosaccharides Or are derived from partial digestion of starches Trisaccharides are most “notorious” Raffinose Stachyose Principally in legumes such as dried peas, beans, lentils Proficient in generating excessive amounts of intestinal gas and flatus 32 Oligosaccharides Fructo-oligosaccharides Polymers of fructose - called inulins Made by plants such as: onions garlic artichokes chicory Appearing as “health foods” Resist human digestive enzymes Promote growth of Bifidobacteria in the large bowel Tend to reduce growth of “undesirable” bacteria 33 Fructo-oligosaccharides and Bifidobacteria Bifidobacteria are beneficial because they: Stimulate immune function Enhance synthesis of B vitamins Restore normal microbial flora after antibiotic therapy Prevent colonization by potential pathogens, especially Clostridia Fructo-oligosacchardies: Reduce triglyceride and cholesterol levels in rats and diabetic humans 34 Disaccharides Principally: Lactose; sucrose; maltose Usually broken down to monosaccharides (“single sugars”) and absorbed in the small intestine When enzymes deficient, disaccharides pass undigested into the colon Have several effects: Change osmotic pressure Act as substrate for microbial fermentation Results in symptoms typical of lactose intolerance; Diarrhea Abdominal bloating Gas Pain 35 Products of Microbial Fermentation of Carbohydrates Any carbohydrate entering the colon acts as substrate (nutrient) for microbial fermentation Principal products are short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs): Acetic acid Propionic acid Butyric acid These three account for 85-95% of SCFAs in the colon 36 Other Sources of SCFAs A smaller percentage of SCFAs come from proteins Up to 40% of SCFAs are derived from protein, depending on the diet Branched chain amino acids are converted to branched chain fatty acids Contribute to the total SCFAs in the colon resulting from microbial activity 37 Products of Microbial Fermentation of Carbohydrates In converting the carbohydrates to these SCFAs intermediate products are formed: Lactate Succinate Ethanol Most do not accumulate, but are converted to SCFAs in the colon However, occasionally ethanol may accumulate: Results in “autobrewery syndrome” resembling alcohol intoxication 38 Function of SCFAs SCFAs absorbed into the body through the colonic membrane (wall), and can be measured in blood SCFAs serve a variety of functions in the colon: Provide source of energy Preserve the integrity of the colonic mucosa (lining) Stimulate absorption of water and sodium Reduce intestinal pH Aid in protection against bacterial infection Butyrate thought to be particularly important in protection against colon cancer May also protect against inflammatory bowel diseases such as ulcerative colitis 39 Proteins in the Colon 12 – 13 grams of protein enter the large bowel each day Material comes from: Diet (even a vegan diet) Secretions from the digestive tract Dead bacteria Tissue cells Much of the material is digested by pancreatic enzymes in the small intestine 40 Proteins in the Colon Pancreatic enzymes continue digestion in the large bowel as they pass in with the digesta from the small intestine Bacterial enzymes actively attack the undigested proteins Bacterial species Bacteroides are particularly active in this process These species are also the most active degraders of fibre in the colon 41 Protein breakdown in the Colon Proteins are first broken down to polypeptides Some bacteria use these directly as nutrients Other bacteria produce enzymes to break down the polypeptides into dipeptides Dipeptides are then broken down further into single amino acids 20 amino acids make up all dietary proteins 42 Amino Acids in the Colon Bacteria utilize the amino acids in a variety of ways: Deamination to ammonia Decarboxylation to amines and carbon dioxide Both systems are important in maintaining a healthy colon 43 Ammonia in the Colon Large quantities almost always present in the colon High levels can be toxic Can be a risk factor in the development of colon cancer Colon bacteria use ammonia as a source of nitrogen in their metabolism These strains are important to maintain a healthy colon These bacteria use carbohydrate, and especially fibre as a course of energy Fibre in the diet thus aids in growth of the ammoniautilizing bacteria, which is thought to reduce the risk of colon cancer 44 Biogenic Amines in the Colon Sometimes the amines are detrimental to a person’s health, e.g. Histamine: Migraine headaches Symptoms resembling allergy Hives Tissue swelling (angioedema) Rhinitis(“stuffy nose”) Itching Reddening and flushing Increased heart rate 45 Biogenic Amines in the Colon Tyramine Migraine headaches Hypertensive crisis Serotonin Piperidine Pyrrolidine Cadaverine Purescine Have adverse effects only in excess and in sensitive individuals 46 Fate of Microbial Products Most microbial products enter circulation by being absorbed through the colon wall Taken to the liver Cleared and excreted in the urine Examples: Phenol and p-cresol from amino acid tyrosine in proteins 50-100 mg per day in the healthy adult urine Level increases with increase in protein in the diet Decreases when bran added to the diet – bran acts as energy source for bacteria that use tyrosine to build bacterial protein 47 Fate of Microbial Products Products of microbial activity normally cleared in the liver and excreted in the urine without adverse effects Scientific data about the fate of many byproducts of microbial metabolism is presently lacking in many cases There is suspicion that in sensitive individuals some “psychological disturbances” following ingestion of certain food materials might be caused by these microbial by-products 48 Protection Against Invading Pathogens Because of its ideal environment, the large bowel may be the site of invasion by disease-causing microorganisms Various factors protect against this: Resident microflora protect their own space SCFAs act as antagonists to many pathogenic microorganisms: Salmonella Shigella (dysentery) Vibrio (cholera) E.coli (enteritis) 49 Invading Pathogens Antibiotics taken by mouth kill off many of the resident species Less SCFAs are produced pH rises Pathogens can now invade and colonize more readily Takes time for the resident micro-flora to reestablish Symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome not uncommon following enteric infections 50 Protection Against Invading Pathogens Diarrheal diseases also decrease SCFAs Microbial infection Lactose intolerance Magnesium-based laxatives Fibre increases level of SCFAs because bacteria that produce them also use fibre as a substrate, which increases bacterial numbers 51 GAS Fermentation always leads to production of various types of gases 80% of the gas from fermentation is released as flatus 20% is absorbed into the body and excreted in breath Volume of gas depends on composition of diet: from 0.5 to 4 litres per day in the adult human 52 Gas Healthy people pass flatus an average of 14 times per day 25 – 100 ml on each occasion Can rise to 168 ml per hour when >50% of the diet is in the form of non-starch fibres and nonabsorbable sugars: Beans Whole grains Some vegetables Some fruits 53 Gases in Breath Principal gases in breath are: Hydrogen Carbon dioxide Small quantities: Methanediol Ethanediol Ammonia Hydrogen sulphide Occasionally Methane Type of gas depends on the presence of the specific bacteria capable of producing it 54 Colonic Gases Some bacteria use gases for their metabolism: Hydrogen metabolized to: Methane Hydrogen sulphide Acetate These may be: utilized by micro-organisms excreted as flatus passed into circulation and breath Amount of hydrogen even from the same amount of substrate is not constant: it depends on: Type of micro-organisms present Speed of fermentation Utilization by other micro-organisms 55 Hydrogen Breath Test for Lactose Intolerance Results of hydrogen breath test used in the diagnosis of lactose intolerance varies depending on type of micro-organisms in the bowel Rationale for test: If lactose is not digested by brush-border lactase, it passes into the large bowel Here it will be fermented by the resident microorganisms, with the production of hydrogen The hydrogen is absorbed, taken in blood to the lungs where it is excreted Amount of hydrogen collected from breath is measured and used as an indication of the degree of lactase deficiency 56 Methane Methane-producing bacteria convert hydrogen to methane 30-50% of healthy adults have methane-producing bacteria in their colon Gas is excreted in the breath Not detectable in children under the age of two years In methane-producers, adult level of methane reached by age 10 years Tends to be familial Methane production does not vary with diet May be associated with: large bowel cancer intestinal polyps ulcerative colitis 57 Hydrogen Sulphide Sulphate-reducing bacteria in the colon convert hydrogen to hydrogen sulphide Methane-producing and sulphide-producing bacteria compete for hydrogen in the colon When the diet is high in foods that contain sulphates, hydrogen-sulphide producing bacteria have an advantage Another source of sulphate is body secretions such as mucins that contain sulphated glycoproteins 58 Sulphate-Containing Foods Sulphates may occur naturally: Some fruits Some vegetables Sulphates may be used as clarifying agents and stabilizers in manufactured foods, such as: Cheeses Egg products Pickles Candied and glazed fruit Flours; breads; cereals; pastas Sugars Wine; beers Nutritional supplements Laxatives; homeopathic remedies; medications 59 Acetate If methane-producing and sulphide-producing bacteria are absent, bacteria may convert hydrogen and carbon dioxide to acetate The extent to which this occurs is unknown Acetate may be used by the body as a source of energy in certain metabolic processes The type of gases excreted as flatus or in breath depends more on the species of micro-organisms colonising the bowel than on the composition of the diet Components of the diet determine the amount of gas produced 60 Vitamins Produced by Bacteria Bacteria not only break down food material (catabolism), they synthesise nutrients (anabolism) from these building blocks Vitamin K Required in blood clotting Menaquinone component of the vitamin is derived from bacterial action on vegetable material mostly in the ileum from where it is absorbed Taken to the liver, where it is complexed with prothrombin 61 Vitamins Produced by Bacteria Vitamin B12 Made solely by micro-organisms in ruminant digestive tract Absorbed through small intestine Passes into meat and milk of the animals Human bacteria (Pseudomonas and Klebsiella) also synthesise B12 5 mcg excreted in feces daily Site of synthesis in humans is large bowel but absorption from here is poor Some people have micro-organisms capable of synthesising B12 in the small intestine 62 Vitamins Produced by Bacteria Biotin Synthesised by bacteria in animals and humans Absorbed in lower ileum Antibiotics can reduce biotin levels in urine, indicating significant reduction in biotin synthesis when bacteria are killed Folic acid Thiamine Produced by bacteria, especially in the large bowel Amount absorbed is inadequate alone, and the vitamins must be provided in food to avoid deficiency 63 Changing the Microbial Flora of the Bowel Diet has very little influence on the types of micro-organisms that colonise the digestive tract Attempts to alter the gut microflora by direct dietary manipulation tend to be frustrating Differences in types and numbers in the bowel of one individual compared to another in the same community, eating the same diet Microflora can be changed by use of oral antibiotics Microflora tends to return to pre-antibiotic types over time 64 Probiotics Food supplement containing live bacterial culture Trials in disease situations such as : Diarrheal diseases Re-establishment of normal flora after antibiotic therapy Inflammatory bowel diseases Fungal disease (e.g. candidiasis) Cancers Cholesterol lowering 65 Probiotics Examples of bacteria: Lactobacilli Bifidobacteria Examples of food supplements containing live culture: Yogurts Fermented milks Fortified fruit juice Powders Capsules Tablets Sprays 66 Prebiotics Non-digestible food ingredients that selectively stimulate a limited number of bacteria, to improve health Examples: Fructo-oligosaccharides Lactulose Galacto-oligosaccharides Provided in: Beverages and fermented milks Health drinks and spreads Cereals, confectionery, cakes Food supplements 67 Synbiotics Combine prebiotics and probiotics Prebiotic substrate should enhance survival of probiotic bacteria Example: Bifidobacteria + fructo-oligosaccharide In order to establish the new species, need to continue to provide live culture, and appropriate substrate 68