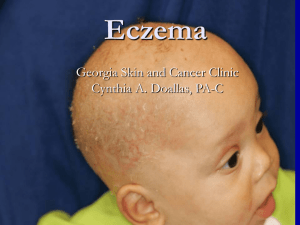

Eczematous Dermatitis

advertisement

Clinical Overview of Eczema/ Dermatitis Rich Callahan MSPA, PA-C ICM I – Summer 2009 Eczema/Dermatitis • Eczema and dermatitis are two different words which essentially have the same meaning: Inflammation of the epidermis and dermis. • This group of diseases includes Atopic Dermatitis, commonly known as “eczema” or “winter dry skin.” • All diseases in this group share the primary characteristics of pruritis, inflammation and disruption of the skin barrier. Eczematous Dermatitis is a family of diseases including: • Non-allergic, or irritant Contact Dermatitis (ICD) • Allergic Contact Dermatitis (ACD) • Atopic Dermatitis, or “Eczema” • Lichen Simplex Chronicus (LSC) • Seborrheic Dermatitis (Dandruff) • All primarily characterized by pruritis, inflammation and scratching. Other Diseases in the Group • Nummular Eczema: A variant of Atopic Dermatitis • Dyshidrosis: A vesicular form of hand dermatitis which often affects patients with a history of atopic dermatitis. Can be precipitated by stress. • Asteatotic Eczema and Stasis Dermatitis: Both are pruritic, eczematous eruptions primarily affecting the lower legs of elderly patients. • Contact Urticaria: Hives brought on by contact with a substance. • We will focus on the more common diseases for this lecture. Dermatitis presents in many different ways • Moderate to Severe – Well-defined, erythematous and edematous plaques with superimposed vesicles, weeping erosions and crusts. • Mild to moderate – Less defined, mildly erythematous to pink plaques with dry adherent scale, superficial desquamation (skin looks peeled off). Sometimes also has pink to erythematous papules mixed in. • Chronic – Pink to purple, thickened, lichenified papules and plaques. Lesions can be quite hyperpigmented in darker-skinned individuals. Constant scratching is the main driving force with these lesions. Urticaria (hives) • Urticaria means an outbreak of wheals (hives) which are caused by contact with an irritant (nonallergic) or an immunologic antigen (allergic.) • Wheals are essentially areas of localized edema in the deep dermis which show at the skin surface as relatively featureless bumps. As you would expect, there are no epidermal changes apparent. • Urticaria can be caused by both external contact with a substance, or internal ingestion. ICD (Non-allergic or Irritant Contact Dermatitis) • Comes from exposure to any irritating substance, and can happen to anyone. Mediated by the substance’s direct toxicity to skin cells. • Can occur immediately after a patient’s first exposure to the substance, or can take months to develop over the course of repeated exposures. • Patients who do a lot of “wet work” either at home or on the job are especially predisposed to contact hand dermatitis as frequent wetting/drying of the hands leads to breakdown of the skin barrier and better penetration of irritating substances. ICD: Clinical Presentation • Large variance in clinical presentation: • Mild/Early: Pink to mildly erythematous patches, or slightly raised papules and plaques. Lesions may/may not be scaly or vesicular. Can be distributed randomly or present in a symmetrical pattern (I.e., if a patient develops ICD from the dye in a new pair of sandals, you could see ICD lesions develop in the pattern the straps make across the top of the foot.) • Severe/Late: Eroded, crusted, fissured patches and plaques which frequently bleed and become secondarily infected. Just about any substance can cause contact dermatitis in the right individual, but here’s a short list of frequent culprits: • Croton oil, kerosene, gasoline, detergents of all kinds, cinnamic, sorbic and benzoic acids, insect stings, moths, nickel, polyethylene glycol, animal keratin (hairs.) Also includes many ingredients in common household and industrial products. Always suspect sizing chemicals in unwashed new clothing. This is but any tiny sample of the potential list. • Clinical Pearl: Topical antibiotics are common contact irritants! Approx. 1/10 of my patients have some sensitivity to neosporin and 1/20 to Bacitracin and Polysporin almost never. Confusing this with bacterial infection can lead to unnecessary antibiotic prescriptions. Switch to straight vaseline when this happens. These cases of ICD often require some detective work to figure out – Clinical Case Example: • Referred by PCP, 52 y/o male city municipal employee presents with recurrent, chronic bilateral hand dermatitis characterized by patches of dry, fissured, desquamated (peeling) skin which were prone to bleeding and secondary infection. • On physical exam lesions were discrete and affected both palms in an asymmetric pattern which suggests chronic contact with a specific object. • The patient mostly operates the same truck, which is a snowplow in the winter. His truck “dumps a lot of salt.” • I had him show me how he habitually holds the steering wheel, and the areas of dermatitis directly corresponded to where his hands would touch it. Hand Dermatitis – The Plot Thickens! • Through further questioning we found that this problem started when the city switched to a new road salt, which he called “magnesium chloride.” • In the winter, his hands were in constant contact with this substance while at work, and he had never cleaned the steering wheel of the truck. Steering wheel described by patient as “totally dirty with caked-on grime.” • Treatment included cleaning the steering wheel, always wearing gloves when in contact with road salt, a course of topical steroids. • The Problem resolved approx. 1 months later. ACD – Clinical Presentation • Poison Ivy is the classic example: Gradual, random development of intensely pruritc papules, vesicular plaques and outright groups of vesicles (blisters) which quickly erode into weepy, crusted lesions. • Tends to be randomly distributed in cases of contact with plants, liquids/powders, etc. • Tends to be arranged in a symmetric pattern when secondary to chronic contact with offending substances in clothing or footwear. Allergic Contact Dermatitis • Poison Ivy is the classic example – a type of delayed type IV hypersensitivity in which a strong sensitizer (like the urushiol resin in poison ivy) is recognized and taken up by Langerhans cells in the epidermis, which then process the urushiol and present it as an antigen to specialized T-cells. The activated T-cells then multiply and spread throughout the entire body, sensitizing all skin surfaces to the offending contactant. • This is why p. ivy can give the illusion of “spreading” over a period of several weeks, leading patients to think they are getting new exposures. Poison Ivy dermatitis does not spread from one part of the body to another. • The main property of urushiol that makes it such an effective contactant is that the molecule has qualities that allow it to penetrate the skin easily to a depth of about 1mm, and then adhere to surrounding cells. • People often don’t recognize they were in poison ivy until way too late, and the oily resin spreads around so well from one object (animate or inanimate,) to another that diverse and scattered areas of the body can become involved. • The hypersensitivity reaction proceeds in a gradual progression around the body, seeming to focus on one area, and then move on to previously unaffected areas. • This is why it can start on the face, move to the chest 3 days later and then to the legs 7 days later. Atopic Dermatitis aka “Eczema” • An inherited disorder usually accompanied by personal/family history of allergic rhinitis, asthma and hay fever. • Characterized by chronically dry, itchy skin which gets scratched/rubbed, breaking down the skin barrier and increasing susceptibility to contact allergens, bacteria and fungi. • Usually first presents before the age of 12, but can rarely start in adulthood also. • Often chronic over periods of months to years. Atopic Dermatitis – Clinical Presentation • When it comes on acutely: Widespread erythematous patches, papules and plaques which are often excoriated and weeping/crusting. Lesions are often scaly. • When it’s chronic: Affected areas become thickened and lichenified (skin markings are accentuated.) Over a period of time, hypopigmentation, fissuring and cracking can develop. • In any case, it’s always itchy. Pruritis is the hallmark of this disease, and because they’re human, patients are inevitably lead to scratch and exacerbate their condition. Atopic Dermatitis – Clinical Presentation • Usually involved areas are ears, face, eyelids, occipital scalp/posterior neck, ventral upper extremity (especially in antecubital regions,) lower legs, popliteal fossae and dorsal feet. • Can be a child with a new diagnosis, or an adult already experienced with the disease. • Usual flare precipitants include stress and onset of cold weather (heat turns on, inside humidity drops, TEWL (transepidermal water loss) increases, skin dries out and becomes itchy, patient starts scratching.) Clinical Pearl: Tinea Incognito –Fungus masquerading as something else • If it scales, scrape it: If you are questioning the diagnosis in a new patient and the lesions have scale, it is always a good idea to scrape it and prepare a KOH slide. Occasionally you will find fungus either masquerading as atopic dermatitis or exacerbating an already existing case. • Also suspect bacterial colonization in all severe cases that respond poorly to treatment or show symptoms and signs suggestive of infection. Topical and oral antibiotics may be necessary. Clinical Presentation – Lichen Simplex Chronicus • Often secondary to chronic Atopic Dermatitis. • Lesions present as lichenified, thickened, well-defined plaques, occasionally scaly, and violaceous to pink color. • Lesions often brown or black in darker-skinned patients. • Driving force formation of LSC is repeated scratching – lesions of crusted and excoriated from recent picking. • Lichenified lesions become hypersensitive over time – lesions itch at the slightest provocation and patients will admit taking great pleasure in itching them. • Male = Female. Any age. Clinical Presentation – Asteatotic Dermatitis • Usually presents in elderly patients, especially those in nursing homes, on arms, legs, hands and occasionally on trunk. • Used to be called “eczema craquele” or “marred with cracks” because skin acquires a cracked-china appearance. • Primary precipitating factors are low indoor relative humidity and over bathing/over washing of the skin. • Lesions are erythematous-to-pink, dry, scaly patches and plaques with “crazy pavement” skin markings. Lesions usually excoriated. Extreme pruritis. Clinical Presentation - Dyshidrosis • Dyshidrosis is a vesicular form of hand (and occasionally foot) dermatitis. Patients often have prior history of AD. • Tends to occur in acute episodes lasting 2-3 weeks each. Often chronic over months to years. • Presents as crops of tiny translucent papules and vesicles on all hand surfaces, which develop over several weeks, rise to the surface and rupture. Secondary cracking, peeling and fissuring are the rule. • Lesions tend to have a classic “tapioca pearl” appearance. Patients often describe burning, itching and tingling. • Usually seen in adults. Men = Women. Clinical Presentation of Seborrheic Dermatitis • Pruritic, scaling dermatitis occurring in areas of skin rich in sebaceous glands: Face, scalp, ears and sternum. • Usually chronic and recurrent over long periods of time. • Men = Women. First episodes in childhood/teenage yrs. • Lesions present as erythematous papules and plaques with loosely adherent yellowish, greasy scale. Scale can be gently peeled back to reveal raw, erythematous skin. • Etiology not entirely understood, but thought to be related to over activity of the yeast Malassezia furfur accompanied by excessive inflammatory response to its presence. Diagnosis of Eczema/Dermatitis • Almost always a clinical diagnosis based on patient history and PE. • Rarely biopsy is needed to diagnose cases with atypical presentation. • Patients with Atopic Dermatitis are usually easy to sort out because they often already have a chronic history of the disease and other features that go along with it like hay fever, allergic rhinitis and history of asthma. • If it scales, scrape it. Diagnosis of Eczema/Dermatitis • In cases of chronic ICD and ACD where poison ivy is not the obvious culprit, allergy patch testing may be necessary to find out what’s causing it. • In these cases it is critical to take a good, thorough history focusing on all skin contactants: Soaps, detergents, fabric softeners, moisturizers, new household/workshop chemicals, shaving cream/aftershave, perfumes, bug sprays, chemicals at work, etc. Also watch for history of recently trying on/wearing new clothes that have never been washed (sizing chemicals,) and heavily colored/dyed clothing warn next to skin on hot day. Treatment • The basic principles of treatment apply to all forms of eczema/dermatitis, as outlined below. Specific variations will be pointed out. • Treatment is geared towards reducing inflammation first and foremost, with secondary goals of • Improving skin hydration/skin barrier through treatment and personal habits. • Preventing/treating secondary infection. • Decreasing pruritis • Decreasing picking/scratching which can perpetuate lesions in some cases. Treatment • Topical Steroids are first line (Classes 1-7.) • Moisturizing emollients. (New line of Rx non-steroidal anti-inflammatory emollients including Mimyx and Atopiclair.) • AD patients need thorough education on appropriate bathing, moisturization, humidification and avoidance of trigger factors. • Interventions include short, tepid showers with moisturizer application immediately after bathing. Limit soap use to groin/axillae. Treatment • Non-steroidal topical anti-inflammatories: tacrolimus (Protopic) and pimecrolimus (Elidel.) Inhibit cutaneous activity of T-Cells. Often used in place of topical steroids when development of skin atrophy is an issue. • Oral/IM steroids. (Don’t under treat poison ivy!) • Immunosuppressants: Cyclosporine and mycophenolate mofetil. Potent drugs with risk/SE profiles – only for cases of severe, refractory AD. Specific Treatments • Seborrheic Dermatitis – topical steroids will clear, but quickly recurs when steroids are withdrawn, leading to dependence and skin atrophy issues. Only exception is scalp, where pulsed treatment with Class 1 topical steroids can provide long-term improvement. • Better treatment strategy is decreasing population of M. furfur yeast and exfoliating the oily scale that it lives in. • Selenium sulfide 1-2.5% shampoos. • Sodium sulfacetamide/Sulfur creams • Ketoconazole shampoos. Specific Treatments • Lichen Simplex Chronicus (LSC) - #1 goal is get the patient to stop scratching. If they stop scratching, will clear in 4-6 weeks. This is easier said than done. • Flurandrenolide (Cordran) tape – steroid-impregnated tape worn over lesions for 12-24 periods of time, 7 days/week, 2 weeks on/1 week off. Has dual function of protecting lesions from direct contact and delivering steroid. • Need to break the itch/scratch cycle for any kind of improvement to occur. • Nocturnal scratching patients may need to wear cotton gloves to bed. Specific Treatments • Dyshidrosis – First line is Class 1 topical steroid ointment under plastic wrap occlusion at qhs; 2 weeks on/1 week off. Acutely vesicular cases may need Burrow’s dressings to desiccate lesion. • In severe cases, occasionally use oral/IM steroids. • Rarely strong immunosuppressants needed to return patient back to ADL’s. (Cyclosporine.) Treatment • Always be on the alert for secondary infection by opportunistic organisms (bacteria/fungus.) Topical steroids/oral steroids/immunosuppressants treat the inflammation of dermatitis, but also dampen the body’s immune response to foreign invaders. Topical steroids = miracle grow for fungus. • Watch for signs including excessive erythema/edema, tenderness to palpation, pus-like exudate and/or history of rapid worsening in one area in short period of time. • Don’t be afraid to perform bacterial cultures/KOH for fungus if indicated clinically! Clinical Pearl: Be wary of treating anything you haven’t seen! • Here’s a clinical case example that will illustrate secondary infection of eczema, and drive home an important lesson: Be wary of treating anything you haven’t seen. • CF was a 22 year old male with long history of Atopic Dermatitis since childhood. He was a typical case with concurrent history of hay fever, allergic rhinitis, multiple environmental allergies and active asthma needing daily use of an inhaler. • I had been treating him for 6 months for a chronic, stubborn patch of AD on his left dorsal foot. Clinical Pearl: Be wary of treating anything you haven’t seen! • The lesion was scraped for KOH at his first visit and no fungal elements were seen. • He was treated chronically with clobetasol 0.05% ointment at qhs, 2 weeks on/1 week off. • We had also recently treated with a short course of oral prednisone with excellent improvement. • After not having seen the patient for several months, we get an urgent phone call from his wife, stating “the rash on the top of his left foot is really bad again, can you call in some more prednisone.” Clinical Pearl: Be wary of treating anything you haven’t seen! • I called CF’s wife back for more information. On further questioning, she recounted a history of sudden, severe worsening of the rash. She said that “his toes are purple and his foot hurts to walk on.” • What I was hearing on the phone was more consistent with infection than severe flare of AD. • I told her I needed to see him within 24 hours, and had the receptionist make a slot for him at the end of the next day. Clinical Pearl: Be wary of treating anything you haven’t seen! • The patient came the following day, removed his Italian leather boots (not a lot of air exchange in there) and showed me his inflamed, purple left foot. • There was a large, scaly erythematous patch with a hint of raised border and central clearing (a characteristic of Tinea Corporis, or “ringworm.”) It was in the same place where his chronic AD patch had been. • Entire left foot was tender to palpation; arterial pulses palpably stronger compared with other foot. Toes had a dusky, violaceous color although cap refill in all digits was good. Clinical Pearl: Be wary of treating anything you haven’t seen! • Dry scale was scraped around the periphery of the lesion with a #15 blade, placed on a glass slide w/1 drop KOH. • Prep was heated and viewed under the microscope. • It was immediately obvious that the specimen was loaded to the gills with fungal hyphae – a sign of severe infection. • Patient treated with oral terbinafine (Lamasil) for 14 days which cleared the rash and all symptoms. • Now think what would have happened if I had just called in another prescription for prednisone instead of having the patient come back in. (Active infection + potent oral immunosuppressant = potential catastrophic worsening of infection.)