Table 1 - The Hospital for Sick Children

advertisement

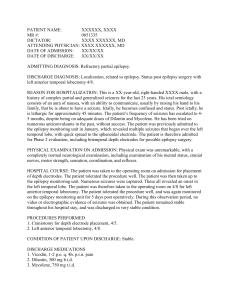

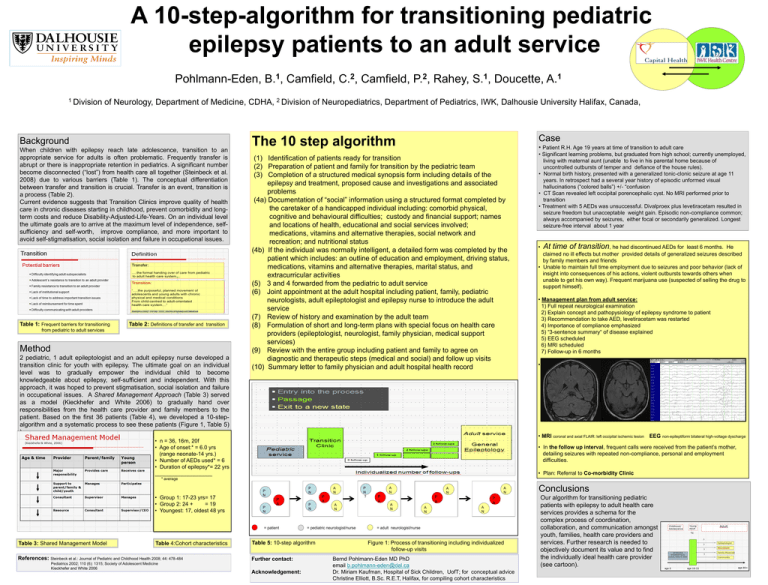

A 10-step-algorithm for transitioning pediatric epilepsy patients to an adult service Pohlmann-Eden, 1 Division 1 B. , Camfield, 2 C. , Camfield, 2 P. , Rahey, 1 S. , Doucette, 1 A. of Neurology, Department of Medicine, CDHA, 2 Division of Neuropediatrics, Department of Pediatrics, IWK, Dalhousie University Halifax, Canada, Background When children with epilepsy reach late adolescence, transition to an appropriate service for adults is often problematic. Frequently transfer is abrupt or there is inappropriate retention in pediatrics. A significant number become disconnected (“lost”) from health care all together (Steinbeck et al. 2008) due to various barriers (Table 1). The conceptual differentiation between transfer and transition is crucial. Transfer is an event, transition is a process (Table 2). Current evidence suggests that Transition Clinics improve quality of health care in chronic diseases starting in childhood, prevent comorbidity and longterm costs and reduce Disability-Adjusted-Life-Years. On an individual level the ultimate goals are to arrive at the maximum level of independence, selfsufficiency and self-worth, improve compliance, and more important to avoid self-stigmatisation, social isolation and failure in occupational issues. Table 1: Frequent barriers for transitioning Table 2: Definitions of transfer and transition from pediatric to adult services Method 2 pediatric, 1 adult epileptologist and an adult epilepsy nurse developed a transition clinic for youth with epilepsy. The ultimate goal on an individual level was to gradually empower the individual child to become knowledgeable about epilepsy, self-sufficient and independent. With this approach, it was hoped to prevent stigmatisation, social isolation and failure in occupational issues. A Shared Management Approach (Table 3) served as a model (Kieckhefer and White 2006) to gradually hand over responsibilities from the health care provider and family members to the patient. Based on the first 36 patients (Table 4), we developed a 10-stepalgorithm and a systematic process to see these patients (Figure 1, Table 5) ). Case The 10 step algorithm • Patient R.H. Age 19 years at time of transition to adult care (1) Identification of patients ready for transition (2) Preparation of patient and family for transition by the pediatric team (3) Completion of a structured medical synopsis form including details of the epilepsy and treatment, proposed cause and investigations and associated problems (4a) Documentation of “social” information using a structured format completed by the caretaker of a handicapped individual including: comorbid physical, cognitive and behavioural difficulties; custody and financial support; names and locations of health, educational and social services involved; medications, vitamins and alternative therapies, social network and recreation; and nutritional status (4b) If the individual was normally intelligent, a detailed form was completed by the patient which includes: an outline of education and employment, driving status, medications, vitamins and alternative therapies, marital status, and extracurricular activities (5) 3 and 4 forwarded from the pediatric to adult service (6) Joint appointment at the adult hospital including patient, family, pediatric neurologists, adult epileptologist and epilepsy nurse to introduce the adult service (7) Review of history and examination by the adult team (8) Formulation of short and long-term plans with special focus on health care providers (epileptologist, neurologist, family physician, medical support services) (9) Review with the entire group including patient and family to agree on diagnostic and therapeutic steps (medical and social) and follow up visits (10) Summary letter to family physician and adult hospital health record • Significant learning problems, but graduated from high school; currently unemployed, living with maternal aunt (unable to live in his parental home because of uncontrolled outbursts of temper and defiance of the house rules). • Normal birth history, presented with a generalized tonic-clonic seizure at age 11 years. In retrospect had a several year history of episodic unformed visual hallucinations (“colored balls”) +/- “confusion • CT Scan revealed left occipital porencephalic cyst. No MRI performed prior to transition • Treatment with 5 AEDs was unsuccessful. Divalproex plus levetiracetam resulted in seizure freedom but unacceptable weight gain. Episodic non-compliance common; always accompanied by seizures, either focal or secondarily generalized. Longest seizure-free interval about 1 year • At time of transition, he had discontinued AEDs for least 6 months. He claimed no ill effects but mother provided details of generalized seizures described by family members and friends • Unable to maintain full time employment due to seizures and poor behavior (lack of insight into consequences of his actions, violent outbursts towards others when unable to get his own way). Frequent marijuana use (suspected of selling the drug to support himself). • Management plan from adult service: 1) Full repeat neurological examination 2) Explain concept and pathopysiology of epilepsy syndrome to patient 3) Recommendation to take AED, levetiracetam was restarted 4) Importance of compliance emphasized 5) “3-sentence summary“ of disease explained 5) EEG scheduled 6) MRI scheduled 7) Follow-up in 6 months • Test results (adult clinic): • MRI coronal and axial FLAIR: left occipital ischemic lesion EEG non-epileptiform bilateral high-voltage dyscharge • n = 36, 16m, 20f • Age of onset:* = 6.0 yrs (range neonate-14 yrs.) • Number of AEDs used* = 6 • Duration of epilepsy*= 22 yrs ___________________ • In the follow up interval, frequent calls were received from the patient’s mother, detailing seizures with repeated non-compliance, personal and employment difficulties. • Plan: Referral to Co-morbidity Clinic * average • Group 1: 17-23 yrs= 17 • Group 2: 24 + = 19 • Youngest: 17, oldest 48 yrs P N P N P A = patient Table 3: Shared Management Model Table 4:Cohort characteristics References: Steinbeck et al.: Journal of Pediatric and Childhood Health 2008; 44: 478-484 Pediatrics 2002; 110 (6): 1315; Society of Adolescent Medicine Kieckhefer and White 2006 A N P N P N Acknowledgement: A N = pediatric neurologist/nurse Table 5: 10-step algorithm Further contact: P A P N ? A N P A A N A N A N P A A N P A A N = adult neurologist/nurse Figure 1: Process of transitioning including individualized follow-up visits Bernd Pohlmann-Eden MD PhD email b.pohlmann-eden@dal.ca Dr. Miriam Kaufman, Hospital of Sick Children, UofT; for conceptual advice Christine Elliott, B.Sc. R.E.T, Halifax, for compiling cohort characteristics Conclusions Our algorithm for transitioning pediatric patients with epilepsy to adult health care services provides a schema for the complex process of coordination, collaboration, and communication amongst youth, families, health care providers and services. Further research is needed to objectively document its value and to find the individually ideal health care provider (see cartoon).