Hospitalization-Associated Disability

advertisement

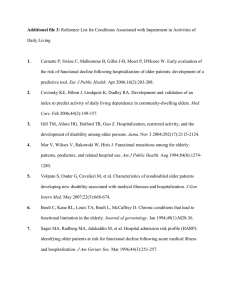

Hospitalization-Associated Disability KENNETH E. COVINSKY, MD, MPH; EDGAR PIERLUISSI, MD; C. BREE JOHNSTON, MD, MPH. JAMA. 2011;306(16):1782-1793 Ryan Mullins MS-III Mercer University School of Medicine Dr. Rahimi- RTR Medical Group Savannah, GA 12/1/2011 Purpose of Discussion In geriatric patients, acute medical illness requiring hospitalization often precipitates disability, resulting in an inability to live independently and complete basic activities of daily living(ADLs). With an incidence of approximately 1/3 of hospitalized patients over the age of 70, hospitalization-associated disability(HAD) represents a problem that must be addressed. This article presents a case of a 70 year old female who developed HAD and explores: risk factors and risk stratification tools that identify geriatric patients at increased risk of HAD; processes that may encourage HAD and models of care developed to prevent it; and methods clinicians can use to improve quality of life in geriatric patients who develop HAD. Case HPI: Ms. N is a 70 y.o. female who presented to the ED with left labial pain and hematuria for 3 days. PMH: DMII, HTN, chronic kidney disease, CAD, PVD, and diabetic neuropathy. SH: Ms. N emigrated from the Philippines in 1997. She was separated from her husband. Prior to admission, she lived independently in a friend’s home and was able to perform all of her ADLs until 3 days before admission. Her monthly income was $300/month from U.S. Social Security Administration. PE: T: 98.2 BP: 155/42 mm Hg P: 55/min RR: 22/min Ms. N appeared frail and shivering. She had a tender, indurated 3 cm mass in the left labium majorum. She was AAO X3 and walked with a normal gait. Lab studies: serum creatinine=10.8 mg/dL; K+=8.3 mEq/L; Hct=19.9%; albumin=3.2 g/dL. Case Continued- Hospitalization Course Day 1- Hemodialysis(HD) was started, and Ms. N received empirical treatment for a UTI. Day 3- I&D of labial lesion. Ms. N was transferred to acute care for elders(ACE) unit. While on ACE unit, Ms. N’s nurse noticed that Ms. N had myoclonus of her extremities, which resulted in difficulty of patient transferring from bed to commode. Mini-Cog screen at that time was negative. The ACE team discontinued Gabapentin at this time, which was started after admission for diabetic neuropathy. 5 days later, myoclonus had resolved, and Ms. N was again independent in ADLs and walking independently using a walker. Ms. N continued having HD 3 times weekly. She was transferred from ACE unit to general medical ward while awaiting outpatient HD slot. Over the next two weeks while on the general medical ward, Ms. N developed progressively worsening difficulty ambulating. Even using a walker, her gait was slow and unsteady. She began needing help using the commode and bathing. Day 30- Ms. N was discharged to a skilled nursing facility. HAD- Incidence HAD- “loss of ability to complete 1 of the basic ADLs needed to live independently without assistance: bathing, dressing, rising from bed or a chair, using the toilet, eating, or walking across a room.” HAD develops between the onset of the acute illness and d/c from hospital. Of patients over the age of 70 hospitalized for a medical illness, at least 30% are discharged from the hospital with an ADL disability that they did not have prior to becoming acutely ill.1,2,3,4 “Approximately 50% of disability among older adults occurs in the setting of medical hospitalization.”1,5 One year post-discharge, less than 50% of geriatric patients have returned to baseline levels of functioning.1,6,7 HAD- Risk Factors Prevention of HAD Physician’s Role in Preventing HAD Incorporating Prevention of HAD Incorporating Prevention of HAD Table 5. Processes of Hospitalization That May Lead to Hospitalization-Associated Disability and Quality Improvement Interventions From Acute Geriatric Units. Covinsky, K. E. et al. JAMA 2011;306:1782-1793 Effect of Disability After the Hospitalization Whether a patient suffering from HAD will be able to live at home after being discharged depends on the patient’s capacity, social support, resources, and environment. Planning a geriatric patient for discharge should include assessing ability to perform ADLs alone or with available assistance. A home equipment evaluation for patients with new disabilities might be necessary to make sure patient’s home is safe (e.g.- stairs, showers, etc.). Patient’s ability to understand medication instructions should be assessed. Prognosis of HAD “In a study of older adults who had developed hospitalization-associated disability, 41% died by 1 year, 29% remained disabled at 1 year, and only 30% returned to their preillness level of function.”1,6 References 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. Covinsky KE, Pierluissi E, Johnston CB. Hospitalization-Associated Disability. JAMA. 2011;306(16):1782-1793. Covinsky KE, Palmer RM, Fortinsky RH, et al. Loss of independence in activities of daily living in older adults hospitalized with medical illnesses: increased vulnerability with age. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(4):451–458. Hirsch CH, Sommers L, Olsen A, Mullen L, Winograd CH. The natural history of functional morbidity in hospitalized older patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1990;38(12):1296–1303. Gill TM, Allore HG, Gahbauer EA, Murphy TE. Change in disability after hospitalization or restricted activity in older persons. JAMA. 2010;304(17):1919– 1928. Gill TM, Allore HG, Holford TR, Guo Z. Hospitalization, restricted activity, and the development of disability among older persons. JAMA. 2004;292(17):2115– 2124. Boyd CM, Landefeld CS, Counsell SR, et al. Recovery of activities of daily living in older adults after hospitalization for acute medical illness. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(12):2171–2179. Brown CJ, Roth DL, Allman RM, Sawyer P, Ritchie CS, Roseman JM. Trajectories of life-space mobility after hospitalization. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(6):372–378.