Anticoagulation Therapy:

New Opportunities, New Challenges

Suraj Kapa, MD

Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania,

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

A REPORT FROM THE 2011 SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS OF THE AMERICAN HEART ASSOCIATION

© 2012 Direct One Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

1

Indications for Oral Anticoagulation

Multiple clinical trials and guideline statements

support the use of long-term oral anticoagulation for

stroke prevention in high-risk patients with atrial

fibrillation (AF).1–8

Long-term oral anticoagulation is also a mainstay in

the management of patients with:

» Mechanical heart valves

» Deep venous thrombosis (DVT)

» Pulmonary embolism

© 2012 Direct One Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

2

Shortcomings of Warfarin

Warfarin therapy requires control of patients’

prothrombin time or international normalized ratio

(INR) within a narrow therapeutic range.

Warfarin levels above the therapeutic range lead to

an increased risk of life-threatening bleeding, and

levels below the therapeutic range obviate any

potential benefits from the drug.

Ensuring maintenance of therapeutic INRs requires

frequent blood testing.

Multiple dietary and pharmacologic interactions may

complicate the maintenance of a therapeutic INR.9,10

© 2012 Direct One Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

3

Thrombus Formation

In AF, the tissue factor pathway is the primary target

for preventing thrombus formation and stroke.12–15

Thrombus formation involves tissue factor-bearing

cells that come into contact with circulating

coagulation factors.

As factor VII comes into contact with tissue factor on

these cells, an activated complex forms, which

triggers factors IX and X.

Factor Xa and factor Va then form prothrombinase

complexes that activate prothrombin to thrombin,

which, in turn, then stimulates factor VII and other

components of the coagulation cascade.

© 2012 Direct One Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

4

Coagulation Cascade

Schematic diagram of the

coagulation cascade along

the tissue factor pathway

and the targets of direct

factor Xa and thrombin

inhibitors. The vitamin K

antagonist warfarin typically

works on several calciumdependent clotting factors,

including factors II, VII, IX

(not shown), and X.

© 2012 Direct One Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

5

Targeting Specific Coagulation Factors

Newer oral anticoagulants target specific points in

the coagulation cascade:

» Factor Xa inhibitors (eg, rivaroxaban, apixaban) target

factor Xa, preventing the conversion of prothrombin to

thrombin.

» Direct thrombin inhibitors (eg, dabigatran, ximelagatran)

target thrombin (factor IIa), blocking the conversion of

fibrinogen to fibrin.

The goal of novel oral anticoagulants is, in part, to

offer more specific targeting and to afford more

predictable responses than current anticoagulant

therapies, such as warfarin, can offer.

© 2012 Direct One Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

6

The Ideal Oral Anticoagulant

Ideally, an oral anticoagulant would:

Require no remote monitoring

Have little interaction with food or other drugs

Offer a good safety profile with regard to bleeding

risk

Have similar efficacy to warfarin in reducing

thromboembolic events

Reach therapeutic levels within several hours

© 2012 Direct One Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

7

Warfarin

When warfarin therapy is started, its anticoagulant

effects may not be apparent for several days.

The duration of action of a single dose is 2–5 days.

The therapeutic effect of warfarin exists within a

narrow therapeutic window as dictated by the INR.

Considerable inter- and intraindividual dose

variability may be affected by a wide range of

physiologic (liver and thyroid function), genetic, and

environmental (eg, diet, other drugs) factors.9,10

Regular monitoring is required to avoid excessive or

insufficient anticoagulation.16

© 2012 Direct One Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

8

Dabigatran

Dabigatran etexilate is a direct thrombin inhibitor

that is given at a fixed oral dose without the need for

INR monitoring.17,18

Because of potential P-glycoprotein (P-gp)

interactions, its absorption may be decreased if

dabigatran is taken with a proton pump inhibitor.19

Excretion may be slowed in patients taking P-gp

pump inhibitors such as quinidine, verapamil, or

amiodarone, raising plasma levels of dabigatran.19

The drug has a relatively short half-life (12–17 hours).

Patients with acute or chronic renal failure may

require reduced doses.17,18

© 2012 Direct One Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

9

Rivaroxaban and Apixaban

Rivaroxaban and apixaban are direct factor Xa

inhibitors.20–23 The two drugs interact slightly

differently with the S4 region of factor X.

Both rivaroxaban and apixaban bind to the

catalytic/active site of factor X and directly interfere

with the coagulation cascade.

They have predictable pharmacokinetics and allow

for fixed oral dosing without the need for INR

monitoring.

Similar to dabigatran, the half-lives of rivaroxaban

and apixaban are under 12 hours.

© 2012 Direct One Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

10

Models of Care: Warfarin Therapy

Routine medical care, wherein a physician or office

staff manage warfarin dosing based on INRs

obtained from blood draws in a laboratory or via a

point-of-care device in the clinic.

Anticoagulation clinics managed by dedicated

healthcare professionals that have systematic

policies to manage and dose patients, using either

point-of-care or laboratory-based INRs.25–27

Patients using a point-of-care monitor at home to

measure their INRs and then reporting back to the

personnel in a clinic to alter the dose.28,29

© 2012 Direct One Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

11

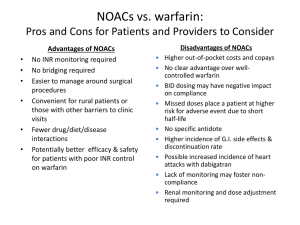

Switching to Newer Oral Anticoagulants

Advantages:

» Fixed oral dosing

» No need to monitor prothrombin time or INR

» Fewer drug interactions

» No dietary restrictions

Disadvantages:

» Lack of validated tests to assay their anticoagulant effect30

» No antidote readily available to halt bleeding

» More difficult to assess patient compliance

» Lack of data on long-term adverse effects beyond bleeding

» Absence of head-to-head comparisons between novel oral

anticoagulants

© 2012 Direct One Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

12

Other Issues with Newer Anticoagulants

Peaks and troughs in anticoagulation levels may

result from their relatively shorter half-lives,

compared with warfarin.

The dosing of these drugs is fixed, so there is no easy

way to measure their therapeutic effects using

specific blood tests.

Additional monitoring of liver and renal function

may be needed to ensure that dose adjustments or

switching of agents is not required.

There is little to educate patients about beyond

compliance.

© 2012 Direct One Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

13

Comparison of Oral Anticoagulants

© 2012 Direct One Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

14

Anticoagulant Therapy and Stroke

Patients with AF-related stroke have a 1.8-fold

increase in mortality when compared with those who

experience a stroke unrelated to AF, possibly

because AF-related strokes tend to be larger in size

and more often lead to hemorrhagic

transformation.2,31,32

Although patients with AF and at least two

additional risk factors for stroke benefit from

warfarin therapy, many patients and their physicians

resist using warfarin because of concerns related to

INR monitoring, the risk of falls, and the potential

for bleeding and intracranial hemorrhage.

© 2012 Direct One Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

15

INR Variability in AF Patients

Randomized clinical trials comparing dabigatran,

apixaban, and rivaroxaban with warfarin have shown

a strong trend toward the superiority of these novel

oral anticoagulants in preventing stroke and in

reducing the rate of intracranial hemorrhage.33–36

However, data from systematic overviews suggest

that patients on warfarin maintain a therapeutic INR

only 63% of the time at best, with even worse results

being observed in community practices.37

The importance of maintaining a minimum INR of

2.0 to obtain effective stroke prevention during

warfarin therapy has been well documented.38–41

© 2012 Direct One Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

16

INR Variability in AF Patients

Analyses of data from the ROCKET AF, RE-LY, and

ARISTOTLE studies have shown no significant

difference in stroke outcomes between patients given

a novel oral anticoagulant and those using

warfarin.33–36,42

However, RE-LY data showed that 50% of patients

using warfarin who had a therapeutic INR at least

67% of the time had a composite event rate of 5.48,

which was lower than the event rates among patients

using dabigatran, whereas patients who were in the

therapeutic range less than 54% of the time had an

event rate of 12.32, which was much worse than the

event rate in patients taking dabigatran.42

© 2012 Direct One Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

17

INR Variability in AF Patients

In the SPORTIF trial, 25% of patients who had the

greatest percentage of time in the therapeutic INR

range had the lowest event rates; however, patients

who were in the therapeutic range less than 60% of

the time had much higher event rates.43,44

In the ATRIA study, there was an 8-fold increase in

ischemic events with any reduction in the INR < 1.3;

if the INR was > 4.0, there was a 12-fold increase in

intracranial hemorrhage.45

© 2012 Direct One Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

18

Self-Monitoring of INR Levels

Self-testing may provide a better way to maintain

INR levels within a narrow therapeutic window.

Results from the THINRS trial suggested beneficial

trends in mortality, major bleeding, and stroke when

patients performed self-testing, rather than relying

on specific clinics for monitoring and managing their

anticoagulation therapy.46–48

Similarly, in the STOARM2 trial, INR management

improved with automated self-monitoring, with INR

values < 1.5 or > 5 seen in only 0.47% of patients.49

© 2012 Direct One Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

19

Self-Monitoring of INR Levels

Other studies have suggested that anticoagulation

clinics run by clinical pharmacists may reduce major

events, hospitalizations, and emergency visits by

60%–80%, when compared with usual clinic-based

management of warfarin, and that weekly INR selftesting and self-management may reduce major

events by as much as 70% and mortality by as much

as 61%.28,29,46–51

Thus, some contend that the primary issue is to fix

how we are managing patients using warfarin rather

than to switch patients to another agent.

© 2012 Direct One Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

20

Cost-Effectiveness

Cost-effectiveness analyses of newer anticoagulants

in preventing stroke in patients with AF are limited.

At a cost of $7–$9/day (two capsules), dabigatran

use may cost an estimated $10,000 per year of life

saved.52–54

However, this analysis does not consider direct

comparisons against the cost of maintaining patients

on warfarin under current models of care.

Further studies are needed to better analyze the

relative cost-effectiveness of warfarin versus that of

any of the newer oral anticoagulants and also to

consider the cost of improving INR management.

© 2012 Direct One Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

21

Potential of Newer Oral Anticoagulants

Newer anticoagulant agents have issues55 not shared

with warfarin, including:

A shorter half-life with rapid offset and potential

attendant clotting risk

The need for a reversal agent in cases of acute

bleeding or at the time of emergent procedures

The lack of laboratory monitoring to evaluate patient

adherence

These newer agents are easy to use, and AF patients can

benefit from lower stroke risk without needing repeated

blood tests for INR monitoring, so the potential

benefits are obvious.

© 2012 Direct One Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

22

Anticoagulant Therapy and DVT

The same concerns related to INR monitoring, the

narrow therapeutic window of warfarin, and the

wide variety of dietary and pharmacologic

interactions with warfarin still exist in treating

patients with DVT.

One key difference in these patients is that the goal is

treating an existing problem rather than preventing

a potential one.56,57

However, the decision to treat as an outpatient

versus as an inpatient is more difficult, because the

time to reach an effective therapeutic range on

warfarin varies from 2 to 5 days.

© 2012 Direct One Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

23

Rivaroxaban vs Warfarin in DVT

In both the EINSTEIN DVT trial, which compared

rivaroxaban with warfarin, and in an extension of the

EINSTEIN trial, which examined the prevention of

recurrent venous thromboembolism with

rivaroxaban, a nonsignificant decrease in mortality

was noted with rivaroxaban therapy.58,59

The study population excluded use of interacting

medications (strong CYP3A4 inhibitors and

inducers) and patients with significantly elevated

liver function tests or renal impairment.

Warfarin-treated patients were within the

therapeutic INR range less than 60% of the time.

© 2012 Direct One Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

24

Dabigatran vs Warfarin in DVT

In the RE-COVER trial, dabigatran was noninferior

to warfarin in treating acute DVT.60

The study population excluded patients if they had

recent unstable cardiovascular disease, baseline liver

function test results that were more than twice the

upper limit of normal, or significant renal

impairment.

As in the EINSTEIN DVT trial and similar clinical

trials in AF, warfarin-treated patients were within

the therapeutic INR range less than 60% of the time.

© 2012 Direct One Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

25

Choosing an Oral Anticoagulant for DVT

Considerations related to the choice of an initial oral

anticoagulant for patients with acute DVT are similar to

those used for patients with AF, namely, the:

Ability to keep the patient on warfarin within

therapeutic INR levels

Costs of individual agents

Unknown long-term risks related to novel

anticoagulants

Lack of clarity regarding efficacy in patients with

significant liver or renal impairment

© 2012 Direct One Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

26

Laboratory Monitoring

Although dabigatran can raise the INR, activated

partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), and thrombin

time, the degree of elevation has not been clearly

associated with its therapeutic effect.61

The ecarin clotting time (ECT)—in which a known

quantity of ecarin is added to the patient’s plasma

and the time to clotting is evaluated—has been

suggested for monitoring the anticoagulant activity

of dabigatran.61

ECT is notably unaffected by heparin or warfarin.61

Recently developed chromogenic dabigatran assays

may permit monitoring serum dabigatran levels.61

© 2012 Direct One Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

27

Laboratory Monitoring

Similarly, an anti-factor Xa level may be used to

evaluate the therapeutic effects of rivaroxaban or

apixaban.61

These assays are not as quickly obtained or as widely

available as is the INR.

Furthermore, therapeutic ranges for these laboratory

tests remain to be determined.

© 2012 Direct One Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

28

Managing Bleeding Complications

There is some evidence that the anticoagulant actions

of dabigatran and rivaroxaban may be reversible.62–65

Preclinical studies suggest that both recombinant

factor VIIa and prothrombin complex concentrate

(PCC) can reverse the effects of dabigatran and

rivaroxaban on bleeding time and aPTT.

Injection of PCC immediately reversed the

anticoagulant activity of rivaroxaban in 12 healthy

human volunteers but had no effect on dabigatraninduced increases in aPTT, ECT, or thrombin time.62

How these blood products might function in actual

emergent clinical situations is unknown.

© 2012 Direct One Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

29

Conclusions

Although the introduction of rivaroxaban, apixaban,

and dabigatran has the potential to revolutionize the

day-to-day care of patients who require oral

anticoagulation therapy, the best use of these drugs

ultimately may need to be determined on a patientby-patient and center-by-center basis.

The efficacy of individual centers in managing INRs,

the ability to safely maintain a therapeutic INR range

in individual patients on warfarin, and the current

lack of a clear methodology for monitoring or

reversing the anticoagulant effects of these new

agents all must be taken into account when a patient

is switched from warfarin to them.

© 2012 Direct One Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

30

Conclusions

The new era of anticoagulant therapy has resulted in

a milieu of studies and evolving guidelines to help

refine the optimum use of these novel agents as more

convenient and possibly safer therapeutic

alternatives to warfarin.

Future studies to examine the cost-effectiveness of

these agents and their impact on individual patients

and systems-based care, as well as head-to-head

comparisons of novel oral anticoagulants, will be the

key to understanding how these novel agents may

enter the current lexicon of anticoagulation.

© 2012 Direct One Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

31

References

1.

Wann LS, Curtis AB, January CT, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA/HRS focused update on the management of

patients with atrial fibrillation (updating the 2006 guideline): a report of the American College of

Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation.

2011;123:104–123.

2.

Fuster V, Ryden LE, Cannom DS, et al. ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 guidelines for the management of patients

with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task

Force on Practice Guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines

(Writing Committee to revise the 2001 guidelines for the management of patients with atrial

fibrillation). Circulation. 2006;114:e257–e354.

3.

The Boston Area Anticoagulation Trial for AF Investigators. The effect of low-dose warfarin on the risk of

stroke in patients with nonrheumatic AF. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:1505–1511.

4.

Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation Investigators. Stroke Prevention in AF Study: final results.

Circulation. 1991;84:527–539.

5.

EAFT (European Atrial Fibrillation Trial) Study Group. Secondary prevention in non-rheumatic atrial

fibrillation after transient ischaemic attack or minor stroke. Lancet. 1993;342:1255–1262.

6.

Petersen P, Boysen G, Godtfredsen J, et al. Placebo-controlled, randomised trial of warfarin and aspirin for

prevention of thromboembolic complications in chronic atrial fibrillation: the Copenhagen AFASAK

study. Lancet. 1989;1:175–179.

7.

Ezekowitz MD, Bridgers SL, James KE, et al. Warfarin in the prevention of stroke associated with

nonrheumatic AF. Veterans Affairs Stroke Prevention in Nonrheumatic Atrial Fibrillation Investigators. N

Engl J Med. 1992;327:1406–1412.

8. Connolly SJ, Laupacis A, Gent M, et al. Canadian Atrial Fibrillation Anticoagulation (CAFA) study. J Am

Coll Cardiol. 1991;18:349–355.

9.

McMillin GA, Vazquez SR, Pendleton RC. Current challenges in personalizing warfarin therapy. Expert Rev

Clin Pharmacol. 2011;4:349–362.

© 2012 Direct One Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

32

References

10. White PJ. Patient factors that influence warfarin dose response. J Pharm Pract. 2010;23:194–204.

11. Lader E, Martin N, Cohen G, et al. Warfarin therapeutic monitoring: is 70% time in the therapeutic range

the best we can do? J Clin Pharm Ther. 2011 Dec 16. Epub ahead of print.

12. Davie EW, Fujikawa K, Kisiel W. The coagulation cascade: initiation, maintenance, and regulation.

Biochemistry. 1991;30:10363–10370.

13. Davie EW. Biochemical and molecular aspects of the coagulation cascade. Thromb Haemost. 1995;74:1–6.

14. McVey JH. Tissue factor pathway. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 1999;12:361–372.

15. Nakamura Y, Nakamura K, Fukushima-Kusano K, et al. Tissue factor expression in atrial endothelia

associated with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: possible involvement in intracardiac thrombogenesis.

Thromb Res. 2003;111:137–142.

16. Hirsh J, Dalen JE, Anderson DR, et al. Oral anticoagulants: mechanism of action, clinical effectiveness, and

optimal therapeutic range. Chest. 1998;114:445S–469S.

17. Redondo S, Martinez MP, Ramajo M, et al. Pharmacological basis and clinical evidence of dabigatran

therapy. J Hematol Oncol. 2011;4:53.

18. Hankey GJ, Eikelboom JW. Dabigatran etexilate: a new oral thrombin inhibitor. Circulation.

2011;123:1436–1450.

19. Liesenfeld KH, Lehr T, Dansirikul C, et al. Population pharmacokinetic analysis of the oral thrombin

inhibitor dabigatran etexilate in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation from the RE-LY trial. J

Thromb Haemost. 2011;9:2168–2175.

20. Perzborn E, Roehrig S, Straub A, et al. Rivaroxaban: a new oral factor Xa inhibitor. Arterioscler Thromb

Vasc Biol. 2010;30:376–381.

21. Laux V, Perzborn E, Kubitza D, Misselwitz F. Preclinical and clinical characteristics of rivaroxaban: a novel,

oral direct factor Xa inhibitor. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2007;33:515–523.

© 2012 Direct One Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

33

References

22. Raghavan N, Frost CE, Yu Z, et al. Apixaban metabolism and pharmacokinetics after oral administration to

humans. Drug Metab Dispos. 2009;37:74–81.

23. He K, Luettgen JM, Zhang D, et al. Preclinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of apixaban, a

potent and selective factor Xa inhibitor. Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2011;36:129–139.

24. Potpara TS, Lip GY. New anticoagulation drugs for atrial fibrillation. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;90:502–

506.

25. Nutescu EA, Bathija S, Sharp LK, et al. Anticoagulation patient self-monitoring in the United States:

considerations for clinical practice adoption. Pharmacotherapy. 2011;31:1161–1174.

26. MacGregor SH, Hamley JG, Dunbar JA, et al. Evaluation of a primary care anticoagulant clinic managed by

a pharmacist. BMJ. 1996;312:560.

27. Edgeworth A, Coles EC. An evaluation of near-patient testing of anticoagulant control in general practice.

Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2010;23:410–421.

28. Gardiner C, Longair I, Pescott MA, et al. Self-monitoring of oral anticoagulation: does it work outside trial

conditions. J Clin Path. 2009;62:168–171.

29. Perera R, Heneghan C, Fitzmaurice D. Individual patient meta-analysis of self-monitoring of an oral

anticoagulation protocol. J Heart Valve Dis. 2008;17:233–238.

30. Lindhoff-Last E, Samama MM, Ortel TL, et al. Assays for measuring rivaroxaban: their suitability and

limitations. Ther Drug Monit. 2010;32:673–679.

31. Wolf PA, Mitchell JB, Baker CS, et al. Impact of atrial fibrillation on mortality, stroke, and medical costs.

Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:229–234.

32. Lin HJ, Wolf PA, Kelly-Hayes M, et al. Stroke severity in atrial fibrillation: the Framingham Study. Stroke.

1996;27:1760–1764.

33. Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S, et al. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N

Engl J Med. 2009;361:1139–1151.

© 2012 Direct One Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

34

References

34.

Patel MR, Mahaffey KW, Garg J, et al. Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. N

Engl J Med. 2011;365:883–891.

35.

Granger CB, Alexander JH, McMurray JJ, et al. Apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial

fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:981–992.

36.

Connolly SJ, Eikelboom J, Joyner C, et al. Apixaban in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med.

2011;364:806–817.

37.

Connolly SJ, Pogue J, Eikelboom J, et al. Benefit of oral anticoagulant over antiplatelet therapy in atrial

fibrillation depends on the quality of international normalized ratio control achieved by centers and

countries as measured by time in therapeutic range. Circulation. 2008;118:2029–2037.

38.

Hart RG, Benavente O, McBride R, Pearce LA. Antithrombotic therapy to prevent stroke in patients with

atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:492–501.

39.

Hylek EM, Go AS, Chang Y, et al. Effect of intensity of oral anticoagulation on stroke severity and

mortality in atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1019–1026.

40.

Van Walraven C, Hart RG, Singer DE, et al. Oral anticoagulants vs aspirin in nonvalvular atrial

fibrillation: an individual patient meta-analysis. JAMA. 2002;288:2441–2448.

41.

Hylek EM, Skates SJ, Sheehan MA, Singer DE. An analysis of the lowest effective intensity of

prophylactic anticoagulation for patients with nonrheumatic atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med.

1996;335:540–546.

42.

Wallentin L, Yusuf S, Ezekowitz MD, et al. Efficacy and safety of dabigatran compared with warfarin at

different levels of international normalised ratio control for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: an

analysis of the RE-LY trial. Lancet. 2010;376:975–983.

43.

Hylek EM, Frison L, Henault LE, Cupples A. Disparate stroke rates on warfarin among contemporaneous

cohorts with atrial fibrillation: potential insights into risk from a comparative analysis of SPORTIF III

versus SPORTIF V. Stroke. 2008;39:3009–3014.

© 2012 Direct One Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

35

References

44. Amouyel P, Mismetti P, Langkilde LK, et al. INR variability in atrial fibrillation: a risk model for

cerebrovascular events. Eur J Intern Med. 2009;20:63–69.

45. Fang M, Go A, Chang Y, et al. Development of a new risk stratification scheme to predict warfarinassociated hemorrhage: the AnTicoagulation and Risk Factors in AF (ATRIA) study. Circulation.

2010;122:A16443. Abstract.

46. Matchar DB, Jacobson AK, Edson RG, et al. The impact of patient self-testing of prothrombin time for

managing anticoagulation: rationale and design of VA cooperative study #481—The Home INR Study

(THINRS). J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2005;19:163–172.

47. Dolor RJ, Ruybalid RL, Uyeda L, et al. An evaluation of patient self-testing competency of prothrombin

time for managing anticoagulation: pre-randomization results of VA Cooperative Study #481—The Home

INR Study (THINRS). J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2010;30:263–275.

48. Matchar DB, Jacobson A, Dolor R, et al. Effect of home testing of international normalized ratio on clinical

events. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1608–1620.

49. Bussey HI. The future landscape of anticoagulation management. Pharmacotherapy. 2011;31:1151–1155.

50. Watzke HH, Forberg E, Svolba G, et al. A prospective controlled trial comparing weekly self-testing and

self-dosing with the standard management of patients on stable oral anticoagulation. Thromb Haemost.

2000;83:661–665.

51. Cromheecke ME, Levi M, Colly LP, et al. Oral anticoagulation self-management and management by a

specialist anticoagulation clinic: a randomised cross-over comparison. Lancet. 2000;356:97–102.

52. Banerjee A, Lane DA, Torp-Pedersen C, Lip GY. Net clinical benefit of new oral anticoagulants (dabigatran,

rivaroxaban, apixaban) versus no treatment in a “real world” atrial fibrillation population: a modelling

analysis based on a nationwide cohort study. Thromb Haemost. 2011 Dec 21. Epub ahead of print.

53. Pink J, Lane S, Pirmohamed M, Hughes DA. Dabigatran etexilate versus warfarin in management of nonvalvular atrial fibrillation in UK context: quantitative benefit-harm and economic analyses. BMJ.

2011;343:d6333. Epub ahead of print.

© 2012 Direct One Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

36

References

54. Freeman JV, Zhu RP, Owens DK, et al. Cost-effectiveness of dabigatran compared with warfarin for stroke

prevention in atrial fibrillation. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:1–11.

55. Eikelboom JW, Wallentin L, Connolly SJ, et al. Risk of bleeding with 2 doses of dabigatran compared with

warfarin in older and younger patients with AF: an analysis of the randomized evaluation of long-term

anticoagulant therapy (RE-LY) trial. Circulation. 2011;31:2363–2372.

56. Jaff MR, McMurtry S, Archer SL, et al. Management of massive and submassive pulmonary embolism,

iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis, and chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: a scientific

statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123:1788–1830.

57. Kearon C, Kahn SR, Agnelli G, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for venous thromboembolic disease: American

College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (8th edition). American College of

Chest Physicians. Chest. 2008;133(suppl):454S–545S.

58. The Einstein Investigators. Oral rivaroxaban for symptomatic venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med.

2010;363:2499–2510.

59. Romualdi E, Donadini MP, Ageno W. Oral rivaroxaban after symptomatic venous thromboembolism: the

continued treatment study (EINSTEIN-Extension study). Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2011;9:841–844.

60. Schulman S, Kearon C, Kakkar AK, et al. Dabigatran versus warfarin in the treatment of acute venous

thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2342–2352.

61. Favaloro EJ, Lippi G, Koutts J. Laboratory testing of anticoagulants: the present and future. Pathology.

2011;43:682–692.

62. Eerenberg ES, Kamphuisen PW, Sijpkens MK, et al. Reversal of rivaroxaban and dabigatran by

prothrombin complex concentrate: a randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover study in healthy subjects.

Circulation. 2011;124:1573–1579.

© 2012 Direct One Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

37

References

63. van Ryn J, Stangier J, Haertter S, et al. Dabigatran etexilate—a novel, reversible, oral direct thrombin

inhibitor: interpretation of coagulation assays and reversal of anticoagulant activity. Thromb Haemost.

2010;103:1116–1127.

64. Battinelli EM. Reversal of new oral anticoagulants. Circulation. 2011;124:1508–1510.

65. Romualdi E, Rancan E, Siragusa S, Ageno W. Managing bleeding complications in patients treated with the

old and the new anticoagulants. Curr Pharm Des. 2010;16:3478–3482.

© 2012 Direct One Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

38