Why the notion of ‘responsibility for

one's health' fails to direct priority

setting in Swedish health care

Paper to be presented at the Conference

"Priorities 2010. Priority Setting in Difficult Economic Times"

Boston, MA, 24 April 2010

Dr. Werner Schirmer

Department of Sociology

Uppsala University

Prof. Dimitris Michailakis

Department of Social Work and Psychology

Faculty of Health and Working Life

University of Gävle/Sweden

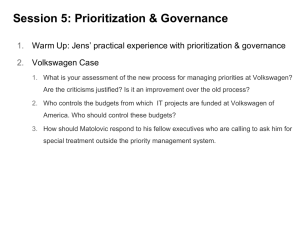

1 Introduction

Ethical Platform: Three Principles for priority-setting as

proposed in 1995

the human dignity principle

the principle of medical need and solidarity

the principle of cost-effectiveness

Evaluations from 2007 showed that these principles failed

they could neither provide guidance to physicians

nor did they contribute to save significant amounts of money

One potential solution suggested:

the notion of responsibility for one's health as a principle for

prioritization

1 Introduction

The aim of this paper:

Scrutinizing the responsibility principle

Theoretical framework:

Theory of society by German sociologist Niklas

Luhmann

2 Legitimacy

If it was for effectiveness only, ascriptive

social attributes (sex, age, class, ethnicity

etc.) would be a suitable ordering principle for

prioritization

However, modern society considers them as

illegitimate

Acceptable candidates for prioritization

criteria must comply with modern values such

as equality and human dignity

2 Legitimacy

3 Prioritization paradox?

The Ethical Platform considers the human

dignity principle as unconditional and

therefore superior other priority principles

This approach seems to be based on a logical

contradiction: unconditional equal value of

human beings contradicts the very idea of

prioritization

Setting priorities means selecting someone

instead of someone else, thus it means

treating supposedly equals as unequals

3 Prioritization paradox?

Prioritization criteria have to derive their

legitimacy in line with the human dignity

principle while factually running counter to

the idea of equal human value

These criteria have to compete with human

dignity – not in terms of legitimacy but of

practicality

What we, then, are looking for are reasonable

exemptions from the human dignity principle

3 Prioritization paradox?

4 Finding reasonable exemptions from

the human dignity principle

The criteria proposed in the Swedish debate on

prioritization can be sorted into two major groups

depending on whether their focus is on

ill/injured human bodies/minds needing treatment

or on a collectivity that has to pay or dispense

In other words, it is either medical rationality or

welfare-political rationality that sets the frame for

priority principles

5 Cause of the problems from 1995

Both the observational perspectives and the reference-

problems of medicine and politics are incompatible

Medicine

The reference is the (ill/injured) human body/mind

Medical communication centres on diseases, organisms,

treatments and healing

Politics

the reference is a collective (e.g. a national population)

Political communication centres on binding decisions and power

It depends on legitimacy and collective support

Therefore, the state is keen on satisfying moral needs such as

equality, solidarity, fair allocation of taxes, and provision of

services (security, education, infrastructure, or healthcare)

5 Cause of the problems from 1995

Since modern society lacks an "Archimedean"

standpoint that can objectively determine

what is more important and what is less,

medical needs are not per se more important

than solidarity and vice versa

Medical and welfare-political criteria cannot

outrank each other

Each can be legitimately rejected on the

grounds of the other

5 Cause of the problems from 1995

6 Solution?

The responsibility principle

A report by The Swedish National Centre for

Priority Setting from 2007 suggested

reactivating the "responsibility principle"

According to this principle, patients are held

responsible for their illness if they conduct an

unhealthy lifestyle (e.g. wrong diet, physical

inactivity, abuse of narcotics) and those who

fail to live up to these expectations can

legitimately be down-prioritized

Unhealthy Lifestyle

points out a scientifically established causal

relation of people's lifestyle and their health

condition

Can be treated as an objective fact and allows

hypothesis-like statements such as "physical

inactivity makes cancer likely"

Responsibility for one's health

Responsibility presupposes the attribution of

agency: has the patient a choice to act

differently, and can thereby be held

responsible, or is she just a victim of

circumstances beyond her control, and

thereby seen non-responsible?

For instance expressed by the statement

"being not physically active, it is your fault if

you become ill with cancer"

Scrutinizing the responsibility principle

The responsibility principle pretends to be a

medical selection but it is a political one

In a medical context, individuals are relevant

as bodies/minds but not as agents

The medical system can establish facts, but is

has no conception of responsibility

The moment of choice that enables the

attribution of responsibility in the causal

relation (lifestyle health outcome) is added

by the political system

Conclusion

The deadlock from 1995 cannot be overcome simply

by introducing a principle based on individual

responsibility for one's health

The connection of responsibility and lifestyle falsely

assumes a subordination of medicine under politics

Responsibility is a political notion building on the

contingent attribution of agency due to current

political interests, there is no corresponding concept

in medicine

(Un)healthy lifestyle assumes causal reasoning

about objectively measureable facts and cannot be

usurped by political logics

Viable solutions have to take seriously that medicine

and politics are each autonomous spheres with

incompatible rationalities