Consultations - Bath GP Training

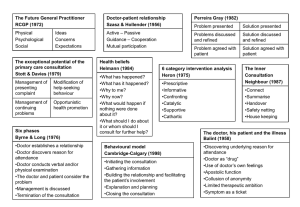

advertisement

Dr Sarah Street Why is it important? Are there problems in communication between doctors and patients? Can clinical communication skills be learnt and do they make a difference? How to learn – skills based approach Consultation models Doctor-patient communication is central to clinical practice ◦ Doctors perform about 200 000 consultations in a professional lifetime Communication is a core skill One of the four essential components of clinical competence: ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ knowledge base communication skills physical examination problem solving ability Communication is not just ‘being nice’ but produces a more effective consultation for both patients and doctors Effective communication significantly improves: ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ accuracy, efficiency and supportiveness health outcomes for patients satisfaction for both patient and doctor the therapeutic relationship How we communicate is just as important as what we say ◦ communication bridges the gap between evidence-based medicine and working with individual patients 45% of patient complaints and 45% of pt concerns not elicited Most patients want their doctors to provide more information than they do Doctors overestimate the time they devote to explanation and planning by up to 90% There are significant problems with patient’s recall and understanding of the information doctors impart On average 50% of medication prescribed is not taken or taken incorrectly Problems in communication is the critical factor in >80% of complaints The longer the doctor waits before interrupting at the start, the more likely they are to discover the full spread of issues the patient wants to discus and the less likely it will be that new complaints arise at the end of the consultation Discovering and acknowledging patients expectations improves patient satisfaction Discovering patient’s expectations leads to greater patient adherence to plans made whether or not those expectations are met by the doctor Patient satisfaction is directly related to the amount of information that patients perceive they have been given by their doctors Content skills – what healthcare professionals communicate Process skills – how they do it Perceptual skills – what they are thinking and feeling An awareness of the structure prevents the consultation from wandering aimlessly and important points from being missed. Essential when it all goes wrong! Models of the consultation ◦ Disease – Illness Model ◦ The Calgary-Cambridge Guide DISEASE ILLNESS MODEL PATIENT PRESENTS PROBLEM Gathering information Parallel search of two frameworks Illness Framework Disease framework Patients agenda Doctors agenda Ideas Symptoms Concerns Signs Expectations Investigations Feelings, Thoughts, Effects Underlying pathology Integration Explanation and planning in terms the patient can understand and accept Understanding the patients unique experience of illness Differential diagnosis I n itia tin g th e se ssio n • p re p a ra tio n • estab lis hing initial r ap p o r t • id e ntif ying th e r easo n(s) fo r the co ns ulta tio n G a th e r in g in fo rm a tio n P ro v id in g S tru ctu r e ex p lo r atio n o f the p a tie nt’s p ro b le m s to d is co ve r the b io m e d ical the p a tie nt’s p ersp ec tive p ers p e ctiv e b ack g ro un d in fo r m a tio n - co n tex t P h y sic a l e x a m in a tio n E x p la n a tio n a n d p la n n in g p ro vid in g the c o rr ec t a m o un t a nd typ e o f info r m a tio n aid ing ac cur a te r ec all an d un d e rsta nd ing ach ie ving a s ha re d u nd ers ta nd ing : inco r p o r a tin g the p a tie nt’s illn ess fra m ew o rk p la nning : s ha re d d e cisio n m a king C lo sin g th e se ssio n • A p p ro p ria te p o in t o f clo s ure • Fo rw ar d p lan nin g B u ild in g t h e r e la t io n s h ip An example of the interrelationship between content and process Gathering information Process skills for exploration of the patient’s problems patient’s narrative question style: open to closed cone attentive listening facilitative response picking up cues clarification time-framing internal summary appropriate use of language additional skills for understanding patient’s perspective Content to be discovered the biomedical perspective (disease) sequence of events symptom analysis relevant systems review the patient’s perspective (illness) ideas and beliefs concerns expectations effects on life feelings background information (context) past medical history drug and allergy history family history personal and social history review of systems Initiating the Consultation Gathering Information Building the Relationship Providing Structure Explanation and Planning ◦ Giving Information ◦ Shared Decision Making Closing the Session Establishing a supportive environment Developing an awareness of the patient’s emotional state Identifying as far as possible all the problems or issues that the patient has come to discuss Establishing an agreed agenda or plan for the consultation Enabling the patient to become part of a collaborative process Preparation ◦ Put aside last task, attends to self comfort ◦ Focus attention and prepares for this consultation Establishing initial rapport ◦ Greeting, introduction, patient’s physical comfort, demonstrate interest and respect Identifying the reasons for the patient’s attendance ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ Opening question Active listening without interruption Screening – check and confirm list of problems or issues Agenda setting Reduces uncertainty for patient and doctor May allow for more efficient and effective use of time Gives more chance for the patient to raise other concerns and identify the most important concern they wish to explore on this occasion Encourages negotiation and mutual partnership Listen to the first problem and allow some of the story to come out Summarise the problems and check you have understood and heard them correctly Acknowledge the problems; show concern verbally and non-verbally Ask for any other problems Prioritise the problems – negotiate which one(s) you will explore on this occasion Useful phrases that people have used? ‘What’s the first thing you’d like to discuss….?’ ‘What’s the one most troubling you….?’ ‘Which one shall we tackle/focus on first/” ‘Which one is the most important to you?’ ‘Let’s start going through them and see where we get to…” ‘We’ll try to deal with as many problems as possible….depending on time/how we get on…’ Exploration of problems ◦ Patient’s narrative ◦ Question style ◦ Listening ◦ Facilitative response ◦ Clarification ◦ Internal summary ◦ Language Understanding the patient’s perspective ◦ Ideas and concerns ◦ Effects ◦ Expectations ◦ Feelings and thoughts ◦ Cues Discuss with your neighbour and feed back to the group. Summarise the problem back to the patient first, then ask: “What was in your mind......?” “What were you concerned/worried about...?” (remember that using the word concern helps patient to disclose their worries; most think that their doctor thinks they may be neurotic if they answer to the word worry) “Was there a particular concern......?” “Tell me what you think the problem is.................have you any clues or theories.....?” “Have you any ideas about................” “Tell me what you think is the cause............” “Do you have any specific worries about..........” “Tell me what was concerning you.......... is it cancer?” (go for it) “Is there anybody else you know who has had this problem?” “Do you think it might be something serious............?” .......... something in particular.....?” “It’s obviously concerning you........is there any particular reason why?” “What in your worst moments did you think it was?” “While you have been waiting to see me ..................... what have been your thoughts?” “During those hours when you have been lying awake at night........what have your thoughts been about the problem?” “Some people with the same sort of symptoms that you have think that they have something serious like cancer.......is that what you have been thinking?” “I’m interested in your ideas about.........I’d like to hear about them because I think they will help us both to understand the problem better.....” “What were your feelings about this?” “I’m sorry to press you, but what was really on your mind....?” What has worked well for you? “What did you think we might ............ “What were you hoping that we might be able to do for this......... “I’m interested in your thoughts about what might be helpful before I make any suggestions........ “Were you hoping that I might do something in particular............ “You’ve obviously given this some thought,.......tell me what you were expecting..... A good strategy is to give a range of options and then ask what the patient was expecting from the consultation; “we could try something to help you with the pain; you might like to see a physiotherapist…..what were you hoping I might do….?” If appropriate, pick up a cue: “you said that your knee was giving you a lot of trouble, I was wondering how that was affecting you……” “I know that you spend a lot of time working for the WRVS/looking after you disabled husband…..tell me how you are coping……” Developing rapport to enable the patient to feel understood, valued and supported Reducing potential conflict between doctor and patient Encouraging an environment that maximises accurate and efficient initiation, information gathering and explanation and planning Enabling supportive counselling as an end in itself Developing and maintaining a continuing relationship over time Involving the patient so they understand and is comfortable with the process of the consultation Increasing both the doctor’s and the patient’s satisfaction with the consultation Non-verbal communication ◦ Demonstrate appropriate non-verbal behaviour ◦ Use of computer ◦ Picks up patient’s non-verbal cues Developing rapport ◦ Acceptance ◦ Empathy and support ◦ Sensitivity Involving the patient ◦ Sharing of thoughts ◦ Provide rational ◦ Examination Can you think of any ways this has worked well for you? Any useful tips – please share with the group. ‘You appear to be in a lot of pain …’ ‘It sounds like a difficult situation.’ ‘That must be really hard for you.’ ‘Is it something that you want to discuss with me?’ ‘You seem very … upset/frustrated/angry/annoyed/ambivalent/ negative/elated.’ ‘You mentioned about ….’ Summarise – end of specific line of enquiry/section of the consultation to verify own interpretation of what patient has said, to ensure no important information omitted Signposting – progress from one section to another using transitional statements; including rational for next section Sequencing – structure consultation in a logical sequence Timing – attend to time and keep consultation on task Gauging the correct amount and type of information to give to each individual patient Providing explanations that the patient can remember and understand Providing explanations that relate to the patient’s illness framework Using an interactive approach to ensure a shared understanding of the problem with the patient Involving the patient and planning collaboratively to increase the patient’s commitment and adherence to plans made Continuing to build a relationship and provide a supportive environment Giving information – checking (Man with Two Brains) http://www.youtube.com/watch?gl=US&v=3r 4rS0yzQ1M Chunk and check Assess patient’s starting point; prior knowledge; extent of wish for information Ask what other information would be helpful Give explanation at appropriate times – avoid giving premature information, advice or reassurance Organise explanation – divide into sections, logical sequence Explicit categorization or signposting Repetition and summarizing Language Visual aids Check understanding Relate explanation to patient’s illness framework: to previously elicited ideas, concerns and expectations Provide opportunities and encourage patient to contribute Pick up and respond to verbal and nonverbal cues Elicit patient’s beliefs, reactions and feelings re information given, terms used; acknowledge and respond Share own thoughts: ideas, thought processes and dilemmas as appropriate Involve patient by making suggestions rather than directives Encourage patient to contribute their thoughts: ideas, suggestions, preferences Negotiate a mutually acceptable plan Offer choices Check with patient: if plans accepted; concerns addressed End summary Contacting – next steps for patient and doctor Safety netting Final checking It is equally important to consider both the medical and patient perspectives of the patient’s problem It is important to gather all relevant information and share an understanding of the issues before moving on to discuss management options A Shared Understanding means that: ◦The Doctor understands the patient’s ideas and views ◦The Patient understands the medical aspects and effects of treatment options Improved clinical communication skills leads to more effective consultations and improved outcomes for both patients and doctors I hear and I forget I see and I remember I do and I understand Old Chinese proverb Discovering the reasons for the patient’s attendance 54% of patients’ complaints and 45% of their concerns are not elicited (Stewart et al. 1979) In 50% of visits, patient and doctor do not agree on the nature of the main presenting problem (Starfield et al. 1981) Gathering information Both a ‘high control style’ and premature focus on medical problems can lead to an overnarrow approach to hypothesis generation and inaccurate consultations (Platt & McMath 1979) Doctors rarely ask their patients to volunteer their ideas and often evade their patients’ ideas and inhibit their expression. Discordance between doctors’ and patients’ ideas and beliefs about the illness is likely to result in poor understanding, adherence, satisfaction and outcome (Tuckett et al. 1985) Explanation and planning ◦ Doctors generally give sparse information to their patients, with most patients wanting more (Waitzkin 1984;Beisecker & beisecker 1990; Pinder 1990) ◦ Doctors overestimate the time they devote to explanation and planning by up to 90% (Waitzkin 1984; Makoul et al. 1995) ◦ Patients and doctors disagree over the relative importance of imparting different types of medical information: patients place the highest value on information about prognosis, diagnosis and causation while doctors overestimate their patients’ desire for information concerning treatment and drug therapy (Kindelan & Kent 1987) Patient adherence ◦ On average 50% of patients do not take their medication at all or take it incorrectly (Meichenbaum & Turk 1987; Butler et al. 1996) ◦ Massively expensive Medio-legal issues ◦ Breakdown in communication between patients and doctors is a critical factor leading to malpractice litigation (Levinson 1994) ◦ Lawyers identified doctors’ communication and attitudes as the prime reason for patients pursuing a malpractice suit in 70% of cases (Avery 1986) ◦ Four communication problems present in >70% of malpractice claims: deserting the patient, devaluing the patient’s view, delivering information poorly and failing to understand patients’ perspective (Beckman et al. 1994) Process of the interview ◦ The longer the doctors waits before interrupting at the beginning of the consultation, the more likely they are to discover the full spread of issues that the patient wants to discuss and the less likely will it be that a new complaint arises at the end of the interview (Beckman & Frankel 1984; Joos et al. 1996) ◦ The use of open rather than closed questions and the use of attentive listening leads to greater disclosure of patients’ significant concerns (Cox 1989; Wissow et al. 1994; Maguire et al. 1996) ◦ The more questions patients are allowed to ask of the doctor, the more information they obtain (Tuckett et al. 1985) Patient satisfaction ◦ Greater ‘patient centredness’ in the consultation leads to greater patient satisfaction (Stewart 1984; Arborelius & Bremberg 1992) ◦ Discovering and acknowledging patients’ expectations improves patient satisfaction (Korsch et al. 1968; Eisenthal & Lazare 1976; Eisenthal et al. 1990) ◦ Patient satisfaction is directly related to the amount of information that patients perceive they have been given by their doctors (Hall et al. 1990) Adherence ◦ Doctors can increase adherence to treatment regimens by explicitly asking patients about knowledge, beliefs, concerns and attitudes to their own illness (Inui et al. 1976; Maimen et al. 1988) ◦ Discovering patients’ expectations leads to greater patient adherence to plans made whether or not those expectations are met by the doctor (Eisenthal & Lazare 1976: Eisenthal et al. 1990) Outcome ◦ Patients who are coached in asking questions of, and negotiating with, their doctor not only obtained more information but actually achieved better blood pressure control in hypertension and improved blood sugar control in diabetes (Kaplan et al. 1989; Rost et al. 1991)