Endometriosis 4-1-11

advertisement

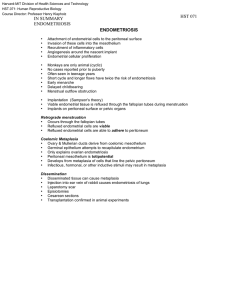

Endometriosis UNC School of Medicine Obstetrics and Gynecology Clerkship Case Based Seminar Series Objectives for Endometriosis Describe the theories of pathogenesis of endometriosis List the most common sites of endometriosis Describe the symptoms and physical exam findings in a patient with endometriosis Describe the diagnosis and management of endometriosis Definition Benign condition in which endometrial glands and stroma are present outside the uterine cavity and walls Occurrence Prevalence of endometriosis in general population unknown Estimated 5-15% of women have some degree of disease Found in 1/3rd or more women with chronic pelvic pain, depending on practice setting Typical patient is in her 30’s, nulliparous, and infertile, but can present throughout the reproductive years. Theories of Pathogenesis Retrograde menstruation (Sampson’s Theory) Endometrial fragments transported through fallopian tubes at time of menstruation and implant at intraabdominal sites Müllerian (Coelomic) metapalasia theory (Meyer’s Theory) Metaplastic transformation of pelvic peritoneum Lymphatic spread (Halban’s Theory) Substances released/shed from endometrium induce formation of endometriosis Theories of Pathogenesis However, since retrograde menstruation is essentially universal, host factors must impact the development of “disease”, such as: • variations in the ability to “clean up” menstrual debris, probably reflecting immunologic events. •Genetic differences in the tendency to develop painful conditions •Medical and psychological comorbidities Sites of Occurrence Ovary (most common) Cul-de-sac Uterosacral ligaments Broad ligament Fallopian tubes Round ligaments Vagina Rectosigmoid and bowel, appendix Urinary bladder and ureters Hacker & Moore: Hacker and Moore's Essentials of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 5th edition (2009), Neville F Hacker, Joseph C Gambone, Calvin J Hobel, Chapter 25 (p299). Symptoms Classic Triad - dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, dyschezia Pain (cyclic and non-cyclic) Infertility Secondary dysmenorrhea Premenstrual and postmenstrual spotting (in about 20%) Physical Exam No pathognomonic finding Don’t forget the recto-vaginal exam! Cul-de-sac nodularity and tenderness Uterosacral nodularity Tender, fixed adnexal mass Uterus fixed and retroverted Differential Diagnosis Chronic pelvic inflammatory disease Recurrent acute salpingitis Hemorrhagic corpus luteum Benign or malignant ovarian neoplasm Ectopic pregnancy Diagnosis Sine qua non – sharp, firm, exquisitely tender “barb” (barbed wire) in uterosacral ligaments Ultrasound – adnexal mass of complex echogenicity, internal echoes consistent with blood Definitive diagnosis Direct visualization (via laparotomy or laparoscopy) Histologic and gross findings consistent with endometrial tissue Other tests Ca125 - not specific nor sensitive Pathology Appearance of endometriosis with back raised lesions of active endometriosis at the time of laparascopy Note: Lesions may be raised or flat with red, black or brown coloration; fibrotic scarred areas that are yellow or white in hue; or vesicle that are pink, clear, or red. Pathology Multiple endometrial cysts “chocolate cysts” of the ovary Pathology Hemorrhage Endometrial stroma Endometrial gland Staging There is no clear relationship between stage and frequency and severity of pain symptoms American Society for Reproductive Medicine revised classification of endometriosis, 1985. (American Fertility Society: Revised American Fertility Society Classification for Endometriosis. Fertil Steril 43:351,1986) Management Key considerations: Severity of the symptoms Extent of the disease Desire for future fertility Age of the patient Threat to GI or urinary tract Management (Medical) 1st line treatment (adequate trial of 3-6 months) NSAIDS OCP’s , cyclic or continuous Progestins (i.e. Medroxyprogesterone acetate) Depression, loss of bone calcium To move beyond these, strongly consider laparoscopy to both diagnose and treat the disease. Medical treatment 2nd line treatment Mirena IUD (levonorgestrel) GnRH agonists (Lupron); should not be done without laparoscopy first; relief of pain does not make the diagnosis of endometriosis Cause hot flashes, vaginal dryness, bone loss High dose progestins – suppress gonadotropin release Cause abnormal bleeding, depression, fluid retention, nausea Danazol – androgenic derivative which suppresses LH and FSH “Pseudomenopause” – anolvulation and hypergonadism Cause weight gain, hirsutism, acne, deepening voice Previously “gold standard,” used rarely now given side effect profile Management (Surgical) Fertility preserving Laparoscopic (or rarely, laparotomy) with ablation or excision of endometrial implants and adhesions Endometriomas >3 cm in diameter should be removed surgically Most definitive Hysterectomy (most often laparoscopic) with ablation or excision of all endometrial implants and adhesions. Removal of ovaries has been traditional, but newer studies suggest retention of ovaries is reasonable in many cases. Always a risk of recurrence! Bottom Line Concepts Typical patient with endometriosis is in her reproductive years, and sub-fertile. Pathogenesis of endometriosis is not completely understood and believed to be a combination of factors. Characteristic triad of symptoms associated with endometriosis is dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, and dyschezia. Staging of endometriosis is not clearly associated with frequency and severity of pain symptoms. Appropriate treatment varies widely and should take into consideration severity of symptoms, extent of disease, and desire for future fertility. There is a risk of recurrence of endometriosis throughout a woman’s life. In all women, minimization of menstrual flow and suppression of ovarian cycling can reduce the risk for endometriosis. References and Resources APGO Medical Student Educational Objectives, 9th edition, (2009), Educational Topic 38 (p80-81). Beckman & Ling: Obstetrics and Gynecology, 6th edition, (2010), Charles RB Beckmann, Frank W Ling, Barabara M Barzansky, William NP Herbert, Douglas W Laube, Roger P Smith. Chapter 29 (p269-276). Hacker & Moore: Hacker and Moore's Essentials of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 5th edition (2009), Neville F Hacker, Joseph C Gambone, Calvin J Hobel. Chapter 25 (p298-303).