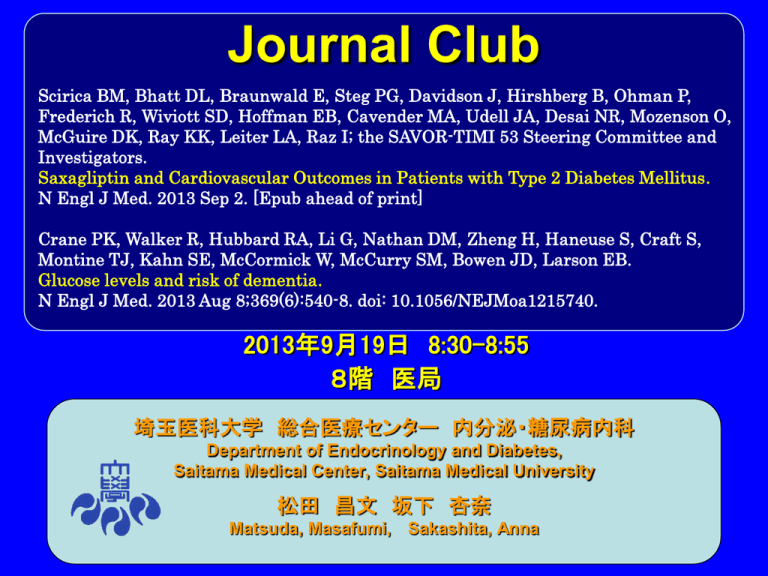

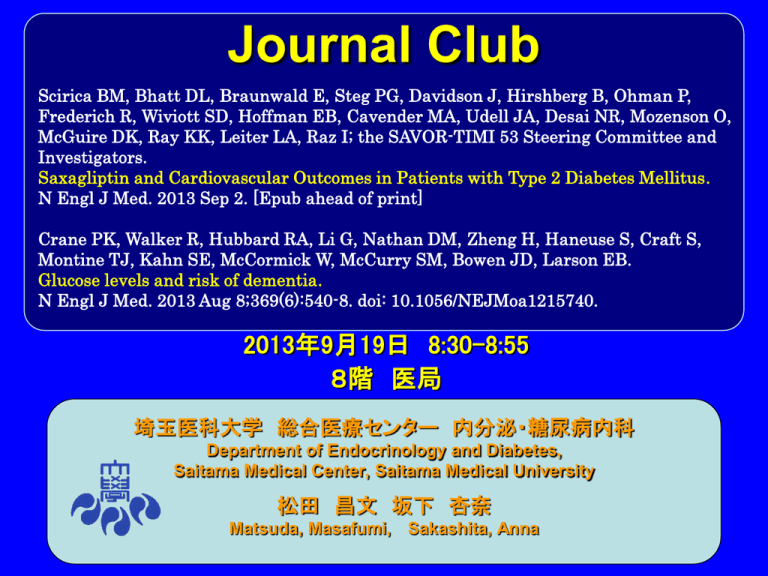

Journal Club

Scirica BM, Bhatt DL, Braunwald E, Steg PG, Davidson J, Hirshberg B, Ohman P,

Frederich R, Wiviott SD, Hoffman EB, Cavender MA, Udell JA, Desai NR, Mozenson O,

McGuire DK, Ray KK, Leiter LA, Raz I; the SAVOR-TIMI 53 Steering Committee and

Investigators.

Saxagliptin and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus.

N Engl J Med. 2013 Sep 2. [Epub ahead of print]

Crane PK, Walker R, Hubbard RA, Li G, Nathan DM, Zheng H, Haneuse S, Craft S,

Montine TJ, Kahn SE, McCormick W, McCurry SM, Bowen JD, Larson EB.

Glucose levels and risk of dementia.

N Engl J Med. 2013 Aug 8;369(6):540-8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215740.

2013年9月19日 8:30-8:55

8階 医局

埼玉医科大学 総合医療センター 内分泌・糖尿病内科

Department of Endocrinology and Diabetes,

Saitama Medical Center, Saitama Medical University

松田 昌文 坂下 杏奈

Matsuda, Masafumi, Sakashita, Anna

DPP-4阻害薬の心血管アウトカム試験

試験名

TECOS

EXAMINE

SAVOR-TIMI 53

CAROLINA

対象

2型糖尿病患者

急性冠症候群を合併 2型糖尿病患者

した2型糖尿病患者

2型糖尿病患者

薬剤名

シタグリプチン

アログリプチン

サクサグリプチン

リナグリプチン

対照薬

プラセボ

プラセボ

プラセボ

グリメピリド

登録例数

14,000例

5,400例

16,500例

6,000例

主要

エンドポイント

心血管死,非致死 心血管死,非致死的 心血管死,非致死

的心筋梗塞,非致 心筋梗塞,非致死的 的心筋梗塞,非致

死的脳卒中,不安 脳卒中の複合

死的虚血性脳卒中

狭心症による複合

の複合

心血管死,非致死

的心筋梗塞,非致

死的脳卒中,不安

狭心症による複合

観察期間

5年間

4.75年間

4年間

8.33年間

試験開始

2008年

2009年

2010年

2010年

試験終了予定

2014年12月

2013年12月

2013年7月

2018年9月

綿田裕孝(順天堂大学大学院代謝内分泌内科学)Pharma Medica ;30,8,157-164.2012.

clinicaltrials.gov(http://clinicaltrials.gov/)をもとに一部改変

the TIMI Study Group, Cardiovascular Division, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and Harvard Medical

School (B.M.S., D.L.B., E.B., S.D.W., E.B.H., M.A.C., J.A.U., N.R.D.), and the VA Boston Healthcare System

(D.L.B.) — all in Boston; INSERM Unité 698, Université Paris-Diderot, and Département HospitaloUniversitaire FIRE, Hôpital Bichat, Assistance Publique–Hôpitaux de Paris, Paris (P.G.S.); the Divisions of

Endocrinology (J.D.) and Cardiovascular Medicine (D.K.M.), Department of Internal Medicine, University of

Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas; AstraZeneca Research and Development, Wilmington, DE

(B.H., P.O.); Bristol-Myers Squibb, Princeton, NJ (R.F.); the Diabetes Unit, Department of Internal Medicine,

Hadassah University Hospital, Jerusalem (O.M., I.R.); the Cardiovascular Sciences Research Centre, St.

George’s University of London, London (K.K.R.); and the Division of Endocrinology and Metabolism,

Keenan Research Centre in the Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute of St. Michael’s Hospital, University of

Toronto, Toronto (L.A.L.).

N Engl J Med 2013. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1307684

Background

The cardiovascular safety and efficacy

of many current antihyperglycemic

agents, including saxagliptin, a

dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4) inhibitor,

are unclear.

Methods

We randomly assigned 16,492 patients with

type 2 diabetes who had a history of, or

were at risk for, cardiovascular events to

receive saxagliptin or placebo and followed

them for a median of 2.1 years. Physicians

were permitted to adjust other medications,

including antihyperglycemic agents. The

primary end point was a composite of

cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction,

or ischemic stroke.

Figure 1. Kaplan–Meier Rates of the Primary and Secondary End Points. The

primary end point (Panel A) was a composite of death from cardiovascular

causes, myocardial infarction, or ischemic stroke.

Figure 1. Kaplan–Meier Rates of the Primary and Secondary End Points. The

secondary end point (Panel B) was a composite of death from cardiovascular

causes, myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, hospitalization for unstable

angina, coronary revascularization, or heart failure.

Results

A primary end-point event occurred in 613 patients in the saxagliptin

group and in 609 patients in the placebo group (7.3% and 7.2%,

respectively, according to 2-year Kaplan–Meier estimates; hazard ratio

with saxagliptin, 1.00; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.89 to 1.12; P =

0.99 for superiority; P<0.001 for noninferiority); the results were similar

in the “on-treatment” analysis (hazard ratio, 1.03; 95% CI, 0.91 to 1.17).

The major secondary end point of a composite of cardiovascular death,

myocardial infarction, stroke, hospitalization for unstable angina,

coronary revascularization, or heart failure occurred in 1059 patients in

the saxagliptin group and in 1034 patients in the placebo group (12.8%

and 12.4%, respectively, according to 2-year Kaplan–Meier estimates;

hazard ratio, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.94 to 1.11; P = 0.66). More patients in the

saxagliptin group than in the placebo group were hospitalized for heart

failure (3.5% vs. 2.8%; hazard ratio, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.07 to 1.51; P =

0.007). Rates of adjudicated cases of acute and chronic pancreatitis

were similar in the two groups (acute pancreatitis, 0.3% in the

saxagliptin group and 0.2% in the placebo group; chronic pancreatitis,

<0.1% and 0.1% in the two groups, respectively).

Conclusions

DPP-4 inhibition with saxagliptin did not

increase or decrease the rate of ischemic

events, though the rate of hospitalization for

heart failure was increased. Although

saxagliptin improves glycemic control, other

approaches are necessary to reduce

cardiovascular risk in patients with diabetes.

(Funded by AstraZeneca and Bristol- Myers

Squibb; SAVOR-TIMI 53 ClinicalTrials.gov

number, NCT01107886.)

Message

心血管イベント高リスクの2型糖尿病(DM)患者

1万6492人を対象に、DPP-4阻害薬saxagliptinの

効果を無作為化試験で評価(SAVOR-TIMI53試

験)。主要複合評価項目(心血管死、心筋梗

塞、虚血性脳卒中)はプラセボ群と同等だっ

た。心不全による入院はsaxagliptin群で多かっ

た(ハザード比1.27)

the Departments of Medicine (P.K.C., W.M., E.B.L.), Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences

(G.L.), Pathology (T.J.M.), and Psychosocial and Community Health (S.M.M.), University of

Washington; the Group Health Research Institute (R.W., R.A.H., E.B.L.); the Department of

Medicine, VA Puget Sound Health Care System and University of Washington (S.E.K.); and

the Swedish Neuroscience Institute ( J.D.B.) — all in Seattle; the Diabetes Center and

Department of Medicine (D.M.N.) and the Biostatistics Center (H.Z.), Massachusetts General

Hospital and Harvard Medical School; and the Department of Biostatistics, Harvard School

of Public Health (S.H.) — all in Boston; and the Department of Internal Medicine, Wake

Forest School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC (S.C.).

N Engl J Med 2013;369:540-8. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215740

Background

Diabetes is a risk factor for dementia. It

is unknown whether higher glucose

levels increase the risk of dementia in

people without diabetes.

Methods

We used 35,264 clinical measurements of glucose levels

and 10,208 measurements of glycated hemoglobin

levels from 2067 participants without dementia to

examine the relationship between glucose levels and the

risk of dementia. Participants were from the Adult

Changes in Thought study and included 839 men and

1228 women whose mean age at baseline was 76

years; 232 participants had diabetes, and 1835 did not.

We fit Cox regression models, stratified according to

diabetes status and adjusted for age, sex, study cohort,

educational level, level of exercise, blood pressure, and

status with respect to coronary and cerebrovascular

diseases, atrial fibrillation, smoking, and treatment for

hypertension.

The sample for the current study was limited to 2067 participants who had at least one

follow-up visit, had been enrolled in Group Health for at least 5 years before study entry,

and had at least five measurements of glucose or glycated hemoglobin (measured as

hemoglobin A1c or as total glycated hemoglobin, with the latter measurement reflecting

an older hemoglobin assay) over the course of 2 or more years before study entry.

Identification of Dementia

Study participants were assessed for dementia every 2 years

with the use of the Cognitive Abilities Screening Instrument,

for which scores range from 0 to 100 and higher scores

indicate better cognitive functioning. Patients with scores of

85 or less underwent further clinical and psychometric

evaluation, including a battery of neuropsychological tests.

The results of these evaluations and laboratory testing and

imaging records were then reviewed in a consensus

conference. Diagnoses of dementia and of probable or

possible Alzheimer’s disease were made on the basis of

research criteria. Dementia-free participants continued with

scheduled follow-up visits. The incidence date for dementia

was recorded as the halfway point between the study visit at

which dementia was diagnosed and the previous visit.

Risk Factors Assessed

Glucose Levels

Diabetes

Apolipoprotein E Genotype

Other Risk Factors

exercise level

smoking status

blood pressure

atrial fibrillation

treatment of hypertension

obesity?

We transformed values for total glycated hemoglobin to

hemoglobin A1c values using this formula:

hemoglobin A1c = (0.6 × total glycated hemoglobin) + 1.7

We then transformed the calculated hemoglobin A1c values to

daily average glucose values with this formula:

daily average glucose = (28.7 × hemoglobin A1c) – 46.7

Nathan DM, Kuenen J, Borg R, Zheng H, Schoenfeld D, Heine RJ. Translating the

A1C assay into estimated average glucose values. Diabetes Care 2008;31:1473-8.

[Erratum, Diabetes Care 2009;32:207.] (ref.10)

Figure S1. Glycemia distribution

throughout the study period.

Dementia, Alzheimer’s Disease, and Glycemia

Over a median follow-up period of 6.8 years, dementia developed in 524 of the

2067 participants (25.4%), including 450 of the 1724 participants who did not

have diabetes at the end of follow-up (26.1%) and 74 of the 343 participants

who had diabetes at the end of follow-up (21.6%). A total of 403 participants

(19.5%) had probable or possible Alzheimer’s disease at the end of follow-up,

55 (2.7%) had dementia from vascular disease, and 66 (3.2%) had dementia

from other causes.

Figure 1. Risk of Incident Dementia Associated with the Average Glucose Level

during the Preceding 5 Years, According to the Presence or Absence of Diabetes.

Solid curves represent estimates of the hazard ratios for the risk of incident dementia

across average glucose levels relative to a reference level of 100 mg per deciliter for

participants without diabetes (Panel A) and 160 mg per deciliter for participants with

diabetes (Panel B). The dashed lines represent pointwise 95% confidence intervals. To

convert the values for glucose to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.05551.

We also found an inverse association

between glucose level and risk of

dementia among people with diabetes

who had relatively low levels of glucose,

although this association appeared to

be driven by glucose levels in three

participants with atypical courses of

type 2 diabetes.

This figure shows spline curves

for the relationship between

glycemia and dementia for

participants with diabetes,

stratified by age at study entry.

Ages at study entry range from

70 in the top left panel to 78 at

the bottom right panel (the

inter‐quartile range of age at

study entry for people with

diabetes). Higher risk

associated with both higher and

lower levels of glycemia appear

to be especially prominent

among people who were older

at study entry. We performed

these analyses for people with

diabetes because of the

suggestive p value for the age

at study entry interaction term

for all‐cause dementia among

people with diabetes (p=0.13).

Results

During a median follow-up of 6.8 years, dementia

developed in 524 participants (74 with diabetes and 450

without). Among participants without diabetes, higher

average glucose levels within the preceding 5 years

were related to an increased risk of dementia (P = 0.01);

with a glucose level of 115 mg per deciliter (6.4 mmol

per liter) as compared with 100 mg per deciliter (5.5

mmol per liter), the adjusted hazard ratio for dementia

was 1.18 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.04 to 1.33).

Among participants with diabetes, higher average

glucose levels were also related to an increased risk of

dementia (P = 0.002); with a glucose level of 190 mg per

deciliter (10.5 mmol per liter) as compared with 160 mg

per deciliter (8.9 mmol per liter), the adjusted hazard

ratio was 1.40 (95% CI, 1.12 to 1.76).

Conclusions

Our results suggest that higher glucose

levels may be a risk factor for

dementia, even among persons without

diabetes.

(Funded by the National Institutes of

Health.)

Message

高齢者における機能変化を検討したAdult

Changes in Thought研究の参加者2067人

(平均年齢76歳)を対象に、血糖値と認知

症の関係を検討。非糖尿病者では過去5年の

平均血糖高値が認知症リスク増加と関連し

(P=0.01)、糖尿病(DM)患者でも平均血

圧高値がリスク増加と関連した

(P=0.002)。