Pseudo-Relatives: Big but Transparent Keir Moulton

advertisement

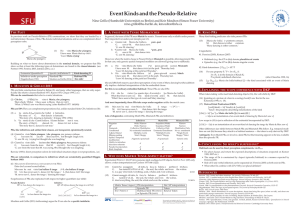

Pseudo-Relatives: Big but Transparent Keir Moulton (Simon Fraser) and Nino Grillo (CLUNL/Stuttgart) It is well known that the size of a clausal complement determines its interpretation: transparent, direct perception complements are expressed by (bare) infinitives, while epistemically non-neutral, indirect perception complements are expressed by finite CPs (Barwise 1981, Higginbotham 1983). Pseudo-relatives (PRs) in Italian (1) are an exception to this generalization. PRs are constituents that consist of a DP subject and a finite CP with a subject gap (Cinque 1992) yet they deliver a transparent perception report like infinitives (2) as shown by the felicity of the continuations in (1) and (2). This is unlike standard finite CPs (3). (1) Gianni ha visto [ [DP Maria] [CP che piangeva] ] . . .ma ha pensato che rideva. Gianni has seen Maria that cry-IMPF . . .but has thought that laugh-IMPF ‘Gianni saw Maria crying . . . but he thought she was laughing. (2) Gianni ha visto Maria piangere . . .ma ha pensato che rideva. Gianni has seen Maria cry-INF . . .but has thought that laugh-IMPF Gianni saw Maria crying but thought she was laughing. (3) Gianni ha visto dalle lacrime che Maria piangeva, #ma ha pensato che stesse ridendo. Gianni has seen from.the tears that Maria cry-IMPF, but has thought that be laughing. ‘Gianni saw from the tears that Maria was crying, #but he thought she was laughing. We will present new data showing that while transparent like infinitives, PRs differ from infinitives with respect to quantification. To capture this three-way distinction between infinitives, PRs, and standard finite clauses, we propose that PRs are headed by a null D which returns an individual situation from a set of topic situations (Portner 1992, Kratzer 1989, 2007). This proposal is the first formal semantic analysis of PRs and it captures their transparency while accommodating their finiteness and quantificational properties. Background What ensures transparency in direct perception reports is see selecting for an individual situation (Barwise 1981), which in the case of infinitives is then quantified by an implicit existential (Higginbotham 1983). Italian infinitives fit this approach (4). Further, this ‘individual-situation’ analysis captures the fact that quantifiers export from perception complements, like the universal in (5). (4) Gianni ha visto Maria piangere. ∃s∃s′ [cry(Maria)(s′ ) & see(s′ )(Gianni)(s)] has seen Maria cry-INF ‘G. saw Maria crying.’ G. nascere. (5) Gianni ha visto tutti i suoi figli Gianni has seen all the his children born.INF ‘Gianni saw all his children being born.’ ∀x∃s[his child(x) → ∃s′ [be born(x)(s′ ) & saw(s′ )(G)(s)]] New data The PR version of (5) can only describe the improbable case in which there is one situation that contains each event of Gianni’s children’s birth and Gianni sees this one large situation on one occasion. (The PR is felicitous if Gianni sees multiple women giving birth in one room at the same time.) (6) #Gianni ha visto tutti i suoi figli che nascevano. Gianni has seen all the his children that born- IMPF ‘Gianni saw all his children being born.’ PRs and infinitives also differ under negation. The existential that quantifies the infinitival complement (4) may scope below matrix negation, in which case it is compatible with the event described by the complement having never happened (7). In contrast, PRs carry an existence commitment which makes (8) infelicitous: Dato che Maria non ha mai ballato, Gianni non ha mai visto Maria ballare il tango. Given that M. NEG has never danced, G. NEG has never seen M. dance the tango. ‘Since M. has never danced, G. has never seen M. dance the tango.’ (8) #Dato che M. non ha mai ballato, G. non ha mai visto M. che ballava il tango Given that M. NEG has never danced, G. NEG has never seen M. that dance- IMPF the tango ‘Since M. has never danced, G. never saw M. dancing the tango.’ (7) 1 Proposal PRs are non-quantificational DPs that denote an individual situation, unlike infinitival complements which denote properties of situations. Direct perception see either takes an individual situation (9a), in the case of PRs, or a property of situations (9b). (9) a. PR-taking see: b. Infinitive-taking see: ! see "=λs′ .λx.λs.see(s′ )(x)(s) ! see "=λP⟨s,t⟩.λx.λs.∃s′ [P(s′ ) & see(s′ )(x)(s)] The transparency of PRs follows because they denote an individual situation not a proposition. We analyze the CP portion of PRs as a property of topic situations, which is supported by the fact that PRs have anaphoric tense (Guasti 1988): for instance, present PR under future has a simultaneous interpretation. (10) Vedr`o Marco che corre. I.will.see Marco that runs- PRES ‘I will see Marco running’ As with sequence-of-tense (Kusumoto 2006), the Kleinian topic situation (s2 ) is abstracted over (11a). Viewpoint aspect, here IMPF, is interpreted as a part relation. The subject originates in the CP (although nothing hinges on this). The determiner that embeds the PR shifts it from ⟨s,t⟩ to type s (11b). (Our working hypothesis is that D ET is a choice functional determiner f (Reinhart 1997, et. seq.) which is provided by context (Kratzer 1998).) (11) [DP D ET [CP che λ2 s2 IMPF Maria piangeva ]] a. ! [CP] " = λs∃s′ [piangeva(m)(s′ ) & s ≤p s′ ] b. ! [DP] " = f(λs∃s′ [piangeva(m)(s′ ) & s ≤p s′ ]) ! the individual picked from the set of s s.t. s is a (topic) situation contained in a situation of Maria crying. (11b) serves as the internal argument of see in (9a) and carries an existence commitment under negation; the same will not be true in the case of the property-type infinitive under negation (9b). The choice function prevents quantifiers from within the PR from out-scoping the perceived events, explaining the interpretation of (6) compared to (5). Syntactic Evidence for DP status PRs can like DPs complement prepositions (12), unlike standard finite CPs. PRs can coordinate with other DPs and trigger plural agreement (13). In both (12) and (13), the PR denotes a situation, not an ordinary individual (cf. Cinque 1992). (12) La vista [P P di [P R Carlo che balla il tango ]] e` da non perdere The sight of Carlo that dance-PRES the tango is to not miss ‘The sight of Carlo dancing the tango is not to be missed’ (Cinque 1992: (35b)) (13) [P R Maria che corre] e [DP l’evento di G. che nasce] sono immagini che non vorrei mai vedere. M. that runs & the.event of G. that born are images that NEG want never see. ‘M. running and the event of G. being born are images I’d never want to see.’ Our analysis further explains why PRs have a distribution similar but not identical to small clauses (Cinque 1992): small clauses but not PRs can complement credere ‘believe’. This follows because believe-verbs select propositions, not individual situations. We also address the implications for apparent extraction from PRs (Koopman and Sportiche 2008) and argue that this arises from a different PR configuration. Barwise, J. 1981. Scenes and other situations. J. of Phil. 78. Cinque, G. 1992. The Pseudo-Relative & Acc-ing construction after verbs of perception. Venice WPL 92.I.2. Guasti, M.T. 1988. La pseudorelative & ph´enomes d’accord. Revista di grammatica generativa 13. Higginbotham, J. 1983. The logic of perceptual reports. J. of Philosophy 80:2. Koopman, H. & D. Sportiche. 2008. The que/qui alternation. UCLA. Kratzer, A. 2007. Situations in Natural Language. Kusumoto, K. Tense in Embedded Contexts. UMass. Portner, P. 1992. Situation theory and the semantics of propositional expressions. UMass. 2