Intent to Remember and Von Restorff

advertisement

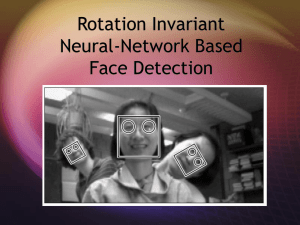

Intent to Remember and Von Restorff (Isolation) Effects Reveal Attentional Processes Richard A. Block and Krista D. Manley Montana State University, Bozeman, Montana Introduction … A classic finding (Von Restorff, 1933) is that subjects remember items that are isolated, distinctive, or salient compared to other items. It is usually measured by free recall of a series of words. The finding of enhanced memory of isolated items is usually attributed to distinctive encoding processes, which may result from enhanced attention to the distinctive items. However, it is unclear exactly what processes produce this effect. One way to decide among the proposed explanations is to assess remembering for an item that immediately preceded or followed a distinct, or isolated, item or items. Memory performance for preceding or following items is compared to performance for other items in the series (i.e., those that were not distinct and did not immediately precede or follow target item or items). Block (2009) found that intent to remember a specific type of picture enhances the subsequent recognition of it. He attributed this to a rapid allocation of attentional resources and an attentional-gate model. Memory was enhanced at even short (0.5 s) presentation durations. Block (in prep.) also found that intent to remember in a similar paradigm significantly enhanced recognition of target pictorial stimuli but had no effect on surrounding items. The present study focused on the possible link between the attentional processes involving both intent to remember and isolation effects. Method Design We used a 3 4 mixed-model design, with 3 between-subjects conditions — Intentional (INT)Framed, Incidental (INC)-Framed, Incidental (INC)-Unframed) — and 4 within-subjects stimulus types — target, preceding, following, neither preceding nor following, and unpresented (new) faces. Subjects A total of 195 male and female college students participated. p1 Target Preceding … Car t1 Following … Filler f2 Results The effect of intent-to-remember (INTFramed) on recognition memory was significantly greater (p < .001) than the effect on either of the incidental conditions (INC-Framed and INCUnframed). This conceptually replicates Block’s (2009) findings. Neither Procedure A total of 53 faces and 18 cars were presented in a 71-item series. Subjects in all three conditions were told to count the number of cars (and most counted 18, as presented). This easy cover task was used by Block (2009) to ensure that subjects in the incidental conditions would not suspect that this was a memory experiment. Stimuli Seven Target (T) faces were randomly assigned to serial positions subject to the constraint that at least one Preceding (P) and one Following (F) face presentation was available. Target faces were framed (see above), except in the Incidental-Unframed condition. Seven neither (N) faces were also used; they did not precede or follow a Target or a Car. Untested (filler) faces were assigned to a total of 16 serial positions, sometimes to ensure that none of the P, F, or N faces would immediately precede of follow a car. Untested (filler) faces were also assigned to the five initial and the five final (primacy and recency buffer) serial positions that cars did not occupy. Seven P and seven F faces were assigned to surround the T faces. Another seven N faces were randomly assigned around filler faces. This effect is also apparent in the three main conditions and each of the four item types. Discussion Intent to remember increased recognition rates for all stimulus types. Isolation did not increase recognition rates, so the isolation effect cannot explain the benefit of recognizing targets found from intent to remember. The Intent-Framed had the highest recognition rates compared to the other conditions, and no stimulus type was significantly higher than the others. The Incidental-Framed condition had higher recognition for Neither stimuli, and the Incidental-Unframed condition had significantly higher recognition for Neither and Targets. This supports the notion that intent to remember may be critical to producing an isolation effect (Wallace, 1965). It could also mean that (a) the unexpected frames were an attentional distraction, (b) that we used more than the usual number of isolated items than in most Von Restorff studies (seven vs. one or just a few), or (c) both. Our main finding is that intent to remember may be needed for isolation, but isolation is not needed for intent-toremember effects. Our findings might help researchers understand the role of intent to remember and the isolation effect as influences on remembering. References Block, R. A. (2009). Intent to remember briefly presented human faces and other pictorial stimuli enhances recognition memory. Memory & Cognition, 37, 667-678. Hunt, R. R. (1995). The subtlety of distinctiveness: What von Restorff really did. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 2, 105-112. Recognition Test Schmidt, S. R. (1991). Can we have a distinctive theory of memory? Memory &: Cognition, 19, 523-542. The subsequent recognition test had 35 faces (7 preceding faces, 7 target faces, 7 following faces, 7 neither preceding nor following any targets or cars, and 7 new faces). Wallace, W. P. (1965). Review of the historical, empirical, and theoretical status of the von Restorff phenomenon, Psychological Bulletin, 63, 410-424.