Descartes - faculty.piercecollege.edu

advertisement

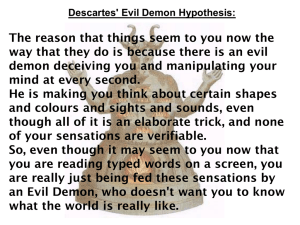

Knowledge, Skepticism, and Descartes Knowing In normal life, we distinguish between knowing and just believing. “I think the keys are in my pocket.” “I know the keys are in my pocket.” “I believe 0.999999999… = 1.” “I know 0.999999999… = 1.” The traditional definition of knowledge In cases where we know a claim, we have good reason to think it is true: we feel the keys in our hands, or we do the math, etc. Knowledge is justified true belief. (This definition goes back to Plato.) To know a claim, you must believe it, it must be true, and you must have good reason to believe it is true. A skeptic is someone who argues that we can’t justify certain types of claims. Skepticism Skepticism = the view that we cannot know that claims of some type are true (= we’re not able to have good reasons to believe they are true). So a religious skeptic thinks we can’t know religious claims, a moral skeptic thinks we can’t know moral claims, etc. We will examine two kinds of skepticism that interest philosophers: skepticism about the external world and skepticism about induction (reasoning about the unobserved). How could you be skeptical of the external world? Normally, we think we know lots of things. I know I am wearing shoes right now, I know that Sacramento is the capital of California, and so on. It would seem crazy to say “I don’t know, I only believe” for any of these beliefs. But there are arguments that we can’t know such claims. Rene Descartes (1596-1650) Descartes was (in our terms) a scientist and mathematician. He invented analytic geometry, demonstrating that geometry can be reduced to algebra. Compare the ancient way of doing geometry with Descartes’: Euclid’s definition of a circle ‘A plane figure contained by one line such that all straight lines falling upon it from one point amongst those lying within the circle (called the center) are equal to one another.’ Descartes’ definition of a circle ‘A circle is all x and y satisfying x² + y² = r² for some constant number r.’ Descartes’ mathematical and scientific achievements Using analytic geometry, problems such as finding the distance between any two points becomes simple algebra. He introduced the use of x, y, and z as variables, and a, b, and c as constants, as well as the standard notations for cubes and roots. He used trigonometry to find the sine-law of the refraction of light (Snell’s law). And he applied this to explain rainbows. Descartes vs. skepticism Descartes lived in a time of intellectual turmoil and uncertainty (the Reformation and the beginning of the Scientific Revolution). He rejected trust in authority and the senses: they were often wrong. But he also wanted to disprove skeptics, to provide a foundation for science. Descartes’ Meditations (1640) At the start of the First Meditation, Descartes points out that, over the course of our lives, we have many false beliefs. Descartes wants to find an absolutely certain start for knowledge: beliefs he can use as the foundations of science. These beliefs must be absolutely certain: they must be immune to any doubt. Cartesian Doubt So Descartes uses doubt, but only to find absolute certainty. Whatever beliefs can withstand the most extreme doubt are absolutely certain. Descartes imagines three extreme forms of doubt: 1. 2. 3. My senses are unreliable I could be dreaming I could be controlled by a godlike demon Descartes’ illusion argument 1. 2. 3. My senses sometimes deceive me in ways that I can’t tell the difference between true and false. If (1), then any belief based on the senses could be false. So, I don’t know beliefs based on the senses. Descartes’ dream argument 1. 2. 3. There is no criterion by which I can be sure that I am not dreaming. If (1), then every belief based on experience could easily be false. So, every belief based on experience is not knowledge. Descartes’ demon argument 1. 2. 3. I cannot prove that there is no demon. If (1), then all of my beliefs could easily be false. So, no beliefs are knowledge. The brain in a vat Skepticism about the external world To sum up: to know something, we need good reason to believe it is true. But if I were a demon-prisoner or brain in a vat, all my reasons would be exactly the same, yet all my beliefs would be false. So those reasons are not good reasons. So there is no good reason to believe there is an external world. What the skeptic isn’t claiming Skeptics don’t claim to know we are brains in a vat. They are saying no one knows one way or the other: we have no good reasons to show that we are or aren’t envatted. Skeptics aren’t just saying we can’t be certain the world is real. They are saying more than that: they are saying you have no good reason to believe the external world over the virtual world in a vat. Skeptics aren’t saying we know nothing. (That would be knowledge!) They are saying we don’t know there is an external world. Descartes’ solution So, after the First Meditation, Descartes’ goal is clear: he must defeat the demon hypothesis. That is, he needs to prove that there is no demon. If he can’t, then he doesn’t have knowledge of the world. The flip side, though, is optimistic: if he can defeat the demon, then he has a foundation for knowledge immune to the most extreme skepticism. Descartes’ solution: Cogito ergo sum 1. 2. 3. I am thinking. Whatever thinks, exists. Therefore, I exist. or: 1. 2. 3. I could be dreaming or be deceived by a demon. But even if I am dreaming, or some demon is deceiving me, then I exist. Therefore, I exist. Descartes’ way back to knowledge Given that “I exist” is absolutely certain, how can we get to the sort of scientific knowledge that Descartes wants to justify? Descartes proposes two reinforcing ways: 1. 2. Prove God exists. Take clear and distinct ideas as the standard of certain knowledge. Descartes’ proof of God 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. We have an idea of God as an infinite, real being. The cause of any idea must have at least as much reality as the idea has. So, there is something with infinite, real being. If there is something with infinite, real being, then it is God. So, God exists. God and knowledge If God exists and is perfect, then God wouldn’t allow us to be deceived by a demon. So Descartes thinks he has disproved the demon hypothesis. Clear and distinct ideas Additionally, Descartes claims that clear and distinct ideas are true. Knowing that ‘I exist’ is an idea I cannot doubt. Anything that meets that standard (that is clear and distinct) is absolutely certain. This is not sense perception, but pure reason: mathematical proof is the best example. So reason gives us genuine knowledge. This is what makes Descartes a rationalist. Descartes: Summary Descartes’ anti-skeptical, rationalist theory of knowledge: “Cogito ergo sum” provides a first example of something known, and reveals what is needed: clear and distinct ideas. Then we prove clearly and distinctly that the idea of God implies a perfect cause, i.e., God. A perfect God cannot deceive, so our faculties must be reliable if used properly (if guided by reason, e.g., math). Parting thoughts on Descartes Descartes thought he had defeated skepticism and laid a rationalist foundation for knowledge (mathematical science). But his extreme version of skepticism was not as easy to defeat as he thought. Reason was key to science, but it still wasn’t clear how we could prove that we have knowledge. The Regress of Justification Suppose that I believe P, and P is to be justified. Its justification will be other beliefs. But then if P is to be justified, these other beliefs must be justified too, and so on… How to prevent an infinite regress? Perhaps some beliefs are justified in a way that does not depend on any other belief. Descartes took this route: foundationalism, taking some beliefs to be selfevident or self-justifying. Avoiding skepticism by redefining knowledge But perhaps the problem was assuming that to know = to have justified true belief. The JTB definition has serious problems: if knowledge must be justified, then an infinite regress implies there is no knowledge. And Gettier counter-examples show JTB is too broad. So what’s important in “knowing”? The Causal Theory of Knowledge An internalist claims knowledge must be justifiable in reasons that the believer is able to be conscious of. An externalist claims that knowledge depends on having a reliable causal connection to whatever makes a belief true, even if that connection is unknown to the believer (“outside the believer’s mind”). Externalism (The Causal Theory of Knowledge) Externalists replace justification (giving reasons) with reliable causation (what happens to make you believe it). The “reliability” in question is that it reliably causes true beliefs. The believer doesn’t have to be aware of how knowing causes true beliefs. Example: you may recognize a musical key without being able to explain it. A challenge for the externalist While externalism promisingly solves regress and Gettier problems, it raises a puzzle of its own: what if a person doubts their own reliably caused beliefs? Suppose a doctor has a real causal ability to recognize illness. But she dismisses it because she doesn’t want to risk a patient’s life on her hunch. Isn’t knowing supposed to guide action? What good is skepticism? Skeptics don’t advance beliefs, since they don’t claim to have good reasons. Someone without beliefs is less likely to do terrible things, and more likely to consider counter-evidence and change their minds. (82% of philosophers are realists about the external world, 5% skeptics, 4% idealists, 9% “other.”)