Surveying I

advertisement

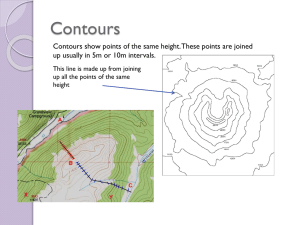

SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) COURSEPACK FOR UG NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/Engr Muhammad Ammar 1 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) o OBJECTIVES o COURSE OUTLINE o DETAILED SYLLABUS o LESSON PLAN NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/Engr Muhammad Ammar 2 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) OBJECTIVES NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/Engr Muhammad Ammar 3 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) OBJECTIVES o To enable students to understand theory and practical of surveying o To develop skills to use the modern survey instruments NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/Engr Muhammad Ammar 4 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) COURSE OUTLINE NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/Engr Muhammad Ammar 5 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) COURSE OUTLINE o COURSE TITLE: SURVEYING – I o COURSECODE: CE – 128 o CREDIT HRS: THEORY: PRAC: 3 2 1 o NO. OF WEEKS: 18 o INSTRUCTOR: ENGR MUHAMMAD AMMAR NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/Engr Muhammad Ammar 6 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) SCHEDULE o WEEK # 01: General Introduction to Survey (Lec 1) o WEEK # 02: Distance Measurement & Chain/Compass Surveying (Lec 2) o WEEK # 03: Plane Table Surveying (Lec 3) o WEEK # 04: Traversing (Lec 4) o WEEK # 05: Traversing (Lec 5) o WEEK # 06: Traversing (Lec 6) NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/Engr Muhammad Ammar 7 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) o WEEK # 07: Leveling (Lec 7) o WEEK # 08: Leveling (Lec 8) o WEEK # 09: Leveling (Lec 9) o WEEK # 10: Contouring (Lec 10) o WEEK # 11: Contouring (Lec 11) o WEEK # 12: Computation of Areas (Lec 12) o WEEK # 13: Computation of Volumes (Lec 13) NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/Engr Muhammad Ammar 8 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) o WEEK # 14: Modern Instruments in Survey (Lec 14) o WEEK # 15: Modern Instruments in Survey (Lec 15) o WEEK # 16: Practical Survey Training (SURVEY WEEK) NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/Engr Muhammad Ammar 9 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) DISTRIBUTION OF MARKS o THEORY 4 x Quiz 2 x Assignment 2 x One Hour Test (OHT) 1 x Final Exam 15 Marks 05 Marks 30 Marks 50 Marks o PRACTICAL* Practical Work/Projects Final (Viva) Performance in field work/attendance 60 Marks 30 Marks 10 Marks * Details will be conveyed to you before the start of survey week NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/Engr Muhammad Ammar 10 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) RECOMMENDED BOOKS o Surveying Principles and Applications by Kavanagh o Surveying and Leveling Vol. 1 by Kanetkar o Surveying for Construction by Irvine (Reference Book) o Surveying Theory and Practice by Davis; McGraw Hill (Reference Book) NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/Engr Muhammad Ammar 11 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) DETAILED SYLLABUS NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/Engr Muhammad Ammar 12 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) DETAILED SYLLABUS 1. GENERAL INTRODUCTION: Definition of survey, principle of survey, types of survey, classification of survey, instruments used in survey, precision and accuracy, accuracy ratio, scale and its construction, distance measurement and use of instrument for distance measurement, errors, distance measured by tape and errors involved, methods of chain surveying and errors involved. 2. PLANE TABLE SURVEYING: Part and accessories of plane table, setting and orientation, methods of plane tabling. 3. TRAVERSING: Methods of traversing, bearings and calculation of angles from bearings, traversing with chain and compass. NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/Engr Muhammad Ammar 13 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) 4. LEVELING: Definitions, types of levels, Staff, principles of leveling, reduction of levels, profile leveling, curvature, refraction, effect of curvature and refraction, corrections, barometric leveling, hypsometry, errors in leveling. 5. CONTOURING: Definitions, characteristics & uses, locating contours, interpolation of contours, setting grade stake for sewers. 6. COMPUTATION OF AREAS: introduction, determination of areas, computation of areas from plans, trapezoidal rule, simpson rule NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/Engr Muhammad Ammar 14 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) 8. COMPUTATION OF VOLUMES: measurement of volumes from crosssections and various formulas for computation of volumes, determination of capacity of reservoir. 9. MODERN METHODS IN SURVEYING: principles of EDMI, EMD characteristics, total station, Global Position System. NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/Engr Muhammad Ammar 15 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) LESSON PLAN NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/Engr Muhammad Ammar 16 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) LECTURE # 01: INTRODUCTION TO SURVEY 1. 2. Definition: - Surveying is the art of making such measurements as will determine the relative positions of distinctive features on the surface of the earth in order that the shape and extent of any portion of earth`s surface may be ascertained and delineated on a map or plan. It is essentially a process of determining positions of points in a horizontal plane. OR Surveying is the art and science of measuring distances, angles & positions, on or near the surface of the earth. “Leveling is art of determining the position of point in vertical plane”. Object of Survey: The primary object of surveying is the preparation of a plan or map. A plan is therefore, the projected representation to some scale, of the ground and the object on the horizontal plane which is represented by the plane of the paper on which the plan is drawn. The representation is called a map, if the scale is small, while it is called a plan, if the scale is large, e.g. a map of UK, a plan of a building. The science of surveying has been developing from the very initial stage of human civilization according to his requirement. Earliest surveys were performed only for the purpose of demarcating its boundaries of plots of land. NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/ Engr Muhammad Ammar 17 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) 3. Due to advancement in technology, the science of surveying has also attained its due importance. In the absence of accurate maps, it is impossible to lay out the alignments of roads, railways, canals, tunnels, transmission power lines, & microwave or television relaying towers. Detailed map of the sites of engineering projects are necessary, therefore, surveying is the first step in the execution of any project Types of Surveys: (1) Plane Surveying and (2) Geodetic Surveying Plane surveying: In plane surveying the curvature of the earth is not taken into account, as the surveys extend over small areas. In dealing with plane surveys, the knowledge of plane geometry & trigonometry is only required. Surveys covering an area up to 260 sq. km may be treated as plane surveys because the difference in length between the arc & the subtended chord on the earth surface for a distance of 18.2km is only 0.1m. Scope & Use of Plane Surveying: Plane Surveys are carried out for engineering projects on sufficiently large scale. They are used for the layout of highways, railways, canals, fixing boundary pillars, construction of bridges etc. For majority of engineering projects, plane surveying is the first step to execute them. NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/ Engr Muhammad Ammar 18 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) Geodetic Surveying: The surveys in which curvature of the earth is taken into account & higher degree of accuracy in linear as well as angular observations is achieved are known as Geodetic Surveying. As the surveys extend over large areas, lines connecting any two points are on the surface of the earth are treated as arcs. A knowledge of spherical trigonometry is necessary for making measurements for the geodetic surveys. Scope & Use of Geodetic Surveying: Geodetic Surveys are conducted with highest degree of accuracy to provide widely spaced control points on the earth’s surface for subsequent plane surveys. In Pakistan, Geodetic Surveys are usually carried out by the survey of Pakistan. 4. Classification Surveys may be classified in a variety of ways: a. Classification based upon the nature of the field of survey: (1) Land Surveys. (2) Hydrographic Surveys. (3) Astronomical Surveys. b. (1) (2) Classification based upon the object of survey: Archaeological Surveys for unearthing relics of antiquity Geological Surveys for determining different strata in the earth’s crust. NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/ Engr Muhammad Ammar 19 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) (3) (4) (5) Mine Surveys for exploring mineral wealth such as gold, coal, etc. Military Surveys for determining points for strategic importance both offensive and defensive. Engineering Surveys for determination of quantities for designing engineering works. c. (1) (2) Classification based upon the methods employed in survey: Triangulation Surveys. Traverse Surveys. d. (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) Classification based upon the instrument employed: Chain Surveys. Theodolite Surveys. Tachometric Surveys. Compass Surveys Plane Table Surveys. Photogrammetric Surveys. NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/ Engr Muhammad Ammar 20 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/ Engr Muhammad Ammar 21 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/ Engr Muhammad Ammar 22 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/ Engr Muhammad Ammar 23 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/ Engr Muhammad Ammar 24 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/ Engr Muhammad Ammar 25 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) 6. Land surveys may be further sub-divided into the following classes: (a) Topographical Surveys for determining the natural features of a country such as hills, valleys. Rivers, nallas, takes, woods, towns, villages etc. (b) Cadastral surveys in which additional details such as boundaries of fields, houses and other properties, path ways, are determined. (c) City Surveys for laying out plots and constructing streets, water supply systems, and sewers. 7. Engineering Surveys may be further sub-divided into: (i) Reconnaissance surveys for determining the feasibility and rough cost of the scheme. (ii) Preliminary surveys for collecting more precise data to choose the best location for the work and to estimate the exact quantities and costs (iii) Location surveys for setting out the work on the ground. 8. Principles of Surveying: various survey methods are based are: NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/ Engr Muhammad Ammar The two fundamental principles upon which 26 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) 1. To work from the whole to the part: The main principle of surveying is to work from the whole to the part. To achieve this in actual practice, a sufficient number of primary control points are established with higher precision in & around the area to be detail surveyed. Minor control points in between the primary control points are then established with less precise method. Further details are surveyed with the help of these minor control points by adopting any one of the survey methods. The main idea of working from the whole to the part is to prevent accumulation of error & to localize minor errors within the framework of the control points. On the other hand, if survey is carried from the part to the whole, the errors would expand to greater magnitudes & the scale of the survey will be distorted beyond control. 2. Location of a point by measurement from two control points: The control points are selected in the area & the distance between them is measured accurately. The line is then plotted to a convenient scale on a drawing sheet. The location of the required point may then be plotted by making two measurements from the given control points as follow: Let A & B be two given control points. Any other point, say D can be located with reference to these points, by any one of the following method: NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/ Engr Muhammad Ammar 27 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) • Rectangular coordinates by the perpendicular dD and the distance Ad. The distance Bd may be measured instead of Ad (fig--) • Trilateration: by the two distances AD and BD (fig--) • Polar coordinates: the angle BAD measured at A and the distance AD. Instead, by angle DBA measured at B and the distance BD (fig--) • Triangulation: by the two angles BAD and ABD measured at A and B (fig---) NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/ Engr Muhammad Ammar 28 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) 9. Scales: - The scale of a map or plan is the fixed proportion which every distance between the locations of the points on the map or plan bears to the corresponding distance between their positions on the ground. Thus if 1 cm on the map represents 10 m on the ground, the scale of the map is 10 m to 1 cm often written simply as 1 cm = 10m. The scale is also expressed by means of a regular fraction whose numerator is invariably unity. The fraction is called “Representative Fraction (R.F)”.For example, if the scale is 10m to 1cm, the R.F. of the scale is Scales of the maps are represented by the following two methods: a). NUMERICAL SCALES b). GRAPHICAL SCALES Characteristics of a Scale Line: a. It should be sufficiently long. (Usually between 18 cm to 27 cm but not more than 32 cm) b. It should be accurately divided and carefully numbered. c. The zero must always be placed between the unit and its subdivisions. d. The name of the scale together with its representative fraction should be written on the plan. e. It should be easily read and should not involve any arithmetic calculation in measuring distance on the map. The main divisions should, therefore, represent one, ten, or hundred units. NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/ Engr Muhammad Ammar 29 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/ Engr Muhammad Ammar 30 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/ Engr Muhammad Ammar 31 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) Plain Scale: On a plain scale it is possible to read only two dimensions such as meters and decimeters, units and tenths etc. Example: Draw a scale 1cm = 4m to read to a meter and show on it 47m. Const: Draw a line 20 cm long and divide it into eight equal parts. Subdivide the first division from the left into 10 equal parts each subdivision reading 1 meter. Place the zero between the subdivided part and the undivided part and mark the figures counting from zero in both dir. To read 47m place one leg of the dividers at 40 and the other at 7. 10. Stages of Survey Operations: The entire work of a survey operation may be divided into three distinct stages: 1. Field work-Reconnaissance, Observations, Field Records 2. Office work-Drafting, Computing, Designing 3. Care & adjustment of the instruments 11. Accuracy Of Surveyed Quantities: Surveyors’ primary objective is to achieve accuracy in their measurements. Survey is of little value if it is not accurate. In surveying, the most common task is to find the 3D positions of a series of NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/ Engr Muhammad Ammar 32 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/ Engr Muhammad Ammar 33 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/ Engr Muhammad Ammar 34 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/ Engr Muhammad Ammar 35 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) points, the x, y & z coordinates. Physical measurements are therefore required in the form of linear, angular & height dimensions. There will be error in these quantities which must be eliminated, discounted or distributed. a). Classification of Errors: Gross: They are simply mistakes. They arise mainly due to the inexperience, ignorance or carelessness of the surveyor. These errors cannot be accommodated & observations have to be repeated. Examples: reading the tape wrongly, recording a wrong dimension when booking, turning the wrong screw on an instrument. Systematic: These are errors which arise unavoidably in surveying & follow some fixed law. Their sources are well known. A simple example is illustrated by the temp error in tape measurements. A tape is only correct at a certain standard temp; therefore if the ambient temp on a certain day is higher or lower than standard, the tape will expand or contract & cause an error which will be the same no matter how often the line is measured. NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/ Engr Muhammad Ammar 36 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) Constant: These are errors which do not vary at any time, in other words, they have the same sign, either positive or negative. As an illustration, consider the nature of the dimensions required for plotting on maps & plans. These must be horizontal & if no attention is paid to the slope of the ground when making a measurement, the dimension so obtained will be too long. No matter how often the measurement is made or how many other slopes are measured, the results will always be too long. Likewise, if a tape has stretched through continuous use, any resultant measurements will always be too short. Constant errors are well known & appropriate corrections are applied to obtain the correct result. Accidental/Random: These are the small errors which inevitably remain after the others have been eliminated. There are three main causes: Imperfections of human sight & touch (human errors), Imperfections of the instruments being used at the time & Changing atmospheric conditions. A good example arises in the measurement of an angle using an instrument called a theodolite. NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/ Engr Muhammad Ammar 37 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) b). Accuracy & Precision: Accuracy & Precision are not synonymous. The difference is illustrated in the following example: A line of survey is measured six times & all six measurements lie within an error band of ± 2mm. However, the tape when checked, is found to have stretched by 10mm through continuous use. The results of the six measurements are precise in that they have little scatter but they are not accurate because each is in error by 10mm. In surveying, accuracy is defined by specifying the limits between which the error of a measured quantity may lie, for example, the accuracy of the measured building might be (20.54 ± 0.01) metres. Accuracy Ratio: The accuracy ratio of a measurement or series of measurements is the ratio of error of closure to the distance measured. The error of closure is the difference between the measured location & the theoretically correct location. To illustrate, a distance was measured & found to be 250.56 ft. The distance was previously known to be 250.50 ft. The error is 0.06 ft in a distance of 250.50 ft. NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/ Engr Muhammad Ammar 38 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/ Engr Muhammad Ammar 39 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) accuracy ratio = 0.06/250.50 = 1/4175 = 1/4200 The accuracy ratio is expressed as a fraction whose numerator is unity & whose denominator is rounded to the closest 100 units. NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/ Engr Muhammad Ammar 40 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) LECTURE: DISTANCE MEASUREMENT Two main methods of determining the distances between points on the surface of the earth. Direct Measurement: distances are actually measured on the surface of the earth by means of chains, tapes etc. Computative Measurement: Distances are determined by calculations indirectly by using the field data as in triangulation, tacheometry etc. Instruments for Measuring Distances: 1). Chain-Gunter’s Chain (66ft), Engineer’s Chain(100ft), Metric Chain(20/30m) 2). Steel Band 3). Tapes-Cloth/Linen Tape, Metallic Tape, Steel Tape, Invar Tape Arrows/Chain Pins: 10 arrows generally accompany a chain, used to mark the end of each chain during the process of chaining. NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/ Engr Muhammad Ammar 41 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/ Engr Muhammad Ammar 42 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/ Engr Muhammad Ammar 43 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/ Engr Muhammad Ammar 44 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) Instruments for Marking Stations: 1). Pegs 3). Ranging Poles 2). Ranging Rods 4). Offset Rod 5). Plumb Bobs Ranging a Line: The process of marking a number of intermediate points on a survey line joining two stations in the field so that the length between them may be measured correctly, is known as ranging. Ranging may be classified as DIRECT RANGING & INDIRECT RANGING Direct Ranging: When intermediate ranging rods are placed along the chain line, by direct observation from either end station, the process is known as direct ranging. Line Ranger: It is a small reflecting instrument used for fixing intermediate points on a chain line. Indirect Ranging: When end stations are not intervisible & the intermediate ranging rods are placed in line by interpolation or by reciprocal ranging or by running an auxiliary line (or random line), the process is known as Indirect Ranging. NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/ Engr Muhammad Ammar 45 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/ Engr Muhammad Ammar 46 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) Degree of Accuracy in Chaining: For comparison of precision of chaining when line of different lengths are measured under dissimilar conditions, it is the usual practice to express the error as ratio (1:n), which is called the chaining ratio. It is the ratio of the error to the distance measured. EXAMPLE: 1/1500, 1/5000 etc. By this is meant an error of 1 unit in 1500 units, or an error of 1 unit in 5000 units The limits of errors under different conditions are as follows: 1). For ordinary measurements with a steel band on flat ground & with careful work: 1 in 2000. 2). For ordinary measurements with a carefully tested chain on fairly level ground & with reasonable care: 1 in 1000. 3). Under average conditions: 1 in 500. 4). For measurements over rough or somewhat hilly ground: 1 in 250. Error in Measurement due to Incorrect Chain Length: “If the chain is too long, the measured distance will be less & if the chain is too short, the measured distance will be more.” a. The true length of line = L´ / L x measured length of line Where L´ = the incorrect length of a chain or tape And L = the true length of a chain or tape Note : Use plus sign when the chain is too long and minus sign when it is too short NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/ Engr Muhammad Ammar 47 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) b. The true area of a plot of a land = (L´/L)2 x Measured area of the plot c. The true volume of an excavation = (L´/L)3 x Measured volume of the excavation Examples on Correction of Distance and Area: 1. The length of a line measured with a 20 m chain was found to be 634.4 m. It was afterwards found that the chain was 0.05 m too long. Find the true length of the line. Solution: True length of line = L’/L x measured length of line. L’ = 20.05 m. L = 20 m. Measured length = 634.4 m. Therefore, True length of the line = 20.05/20x 634.4 = 635.00 m. NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/ Engr Muhammad Ammar 48 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) 2. The length of a line measured by means of a 20 m chain was found to be 610.2 m known to be 612.0 m. What was the actual length of the chain? Solution: Since the measured length of the line is less than its true length, the chain was too long. Now true length of the line = L’/L x measured length. True length of the line = 612.0 m. Measured length of the line = 610.2 m. L = 20.0 m. :. 612.0 = L’/20.0 x 610.2 :. L’ = 612.0x20.0/610.2=20.066 m. 3. A 20 m chain was found to be 0.05 m too long after chaining 1400 m. It was found to be 0.1 m too long after chaining 2200 m. If the chain was correct before commencement of the work find the true distance. Solution: a. Since the chain was correct i.e. 20 m long at the beginning and was 20.05 m long after chaining 1400 m, the increase in length was gradual. :. Mean elongation = 0+0.05/2=0.025 m. :. True distance = 20.025/20 x 1400 = 1401.75m. NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/ Engr Muhammad Ammar 49 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) b. The remaining distance (2200-1400) = 800 m was measured with the same chain. If was 0.05 m too long at the commencement of chaining and 0.10 m too long at the end of chaining. :. Mean elongation = 0.05+0.10/2 = 0.075 m. True distance = 20.075/20 x 800 = 803.00m. where, total true distance = 1401.75 + 803.00 m. = 2204.75 m. CHAINING ON SLOPING GROUNDS: 1). Chaining on the surface of a sloping ground gives the sloping distance. 2). For plotting the surveys, horizontal distances are required. 3). It is therefore, necessary either to reduce the sloping distances to horizontal equivalents or to measure the horizontal distances between the stations directly. 4).Two methods for getting the horizontal distance between two stations on a sloping ground: DIRECT METHOD & INDIRECT METHOD NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/ Engr Muhammad Ammar 50 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) Fig. DIRECT METHOD: Horizontal distances are measured on the ground in short horizontal lengths. Also known as ‘Stepping Method’. NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/ Engr Muhammad Ammar 51 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) Fig. INDIRECT METHOD: Measuring the slope angle with a CLINOMETER Fig. INDIRECT METHOD: Measuring the slope angle from Difference in Elevations NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/ Engr Muhammad Ammar 52 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) Fig. INDIRECT METHOD: Hypotenusal Allowance Correction Method NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/ Engr Muhammad Ammar 53 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) ERRORS IN CHAINING: 1). Cumulative Errors 2). Compensative Errors o CUMULATIVE ERRORS: The errors which occur in the same direction & tend to accumulate, or to add up are called Cumulative Errors. Such errors make the apparent measurements always either too long or too short. a). Positive Cumulative Errors: Those errors which make the measured lengths more than the actuals are known as positive cumulative errors. These are caused in the following situations: i). The length of the chain or tape is shorter than its standard length. ii). The slope correction ignored while measuring along the sloping ground. iii). The sag correction, if not applied, when the chain or tape is suspended at its ends. iv). Due to incorrect alignment. v). Due to working in windy weather. NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/ Engr Muhammad Ammar 54 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) b). Negative Cumulative Errors: The errors which make the measured lengths less than the actuals are known as negative cumulative errors. These are caused in the following situations: i). The length of the chain or tape is greater than its standard length. o COMPENSATING ERRORS: The errors which are liable to occur in either direction & tend to compensate are called compensating errors. These are caused in the following situations: i). Incorrect holding of the chain ii). The chain is not uniformly calibrated throughout its length iii). Refinement is not made in plumbing during stepping method COMMON MISTAKES IN CHAINING: i). Displacement of the arrows ii). Failure to observe the zero point of the tape iii). Adding or omitting a full chain length iv). Reading from the wrong end of the chain v). Reading numbers wrongly/ Reading wrong meter marks vi). Wrong recording in the field book viii). Calling numbers wrongly NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/ Engr Muhammad Ammar 55 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) CORRECTIONS FOR LINEAR MEASUREMENTS: i). Correction for standard length ii). NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/ Engr Muhammad Ammar 56 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/ Engr Muhammad Ammar 57 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/ Engr Muhammad Ammar 58 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/ Engr Muhammad Ammar 59 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/ Engr Muhammad Ammar 60 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/ Engr Muhammad Ammar 61 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/ Engr Muhammad Ammar 62 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/ Engr Muhammad Ammar 63 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/ Engr Muhammad Ammar 64 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/ Engr Muhammad Ammar 65 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/ Engr Muhammad Ammar 66 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/ Engr Muhammad Ammar 67 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/ Engr Muhammad Ammar 68 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/ Engr Muhammad Ammar 69 SURVEYING – I (CE- 128) NUST Institute of Civil Engineering/ Engr Muhammad Ammar 70